by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

In Write Your Novel From the Middle, I explain a crucial moment in a plot where the lead character must make a choice. It usually involves a moral dilemma, with the character’s realization of who he is and how his flaws affect the characters around him. He then has to make a decision about what kind of person he is going to be: Stay the same and continue to hurt people? Or find his way to redemption?

In the middle of Casablanca, for example, we see Rick being a mean drunk toward Ilsa, who has just poured her heart out to him explaining why she had to leave him in Paris. As soon as she tearfully exits the scene, Rick drops his head into his hands, and we know he’s looking with disgust at himself, as if in a mirror. That’s why I call this the “mirror moment” which usually happens smack dab in the middle of a novel or film. Indeed, it is the moment that tells us what the story is really all about.

Casablanca does something else to magnify Rick’s dilemma—it places Rick between two characters who represent opposite moral poles. On one side is Louis Renault, the corrupt French police captain whose sole purpose in life is holding on to his cushy job and bedding desperate women trying to get out of Casablanca. He isn’t loyal to the French or the Germans; he’s loyal to Louis, and does what he can to keep from rocking the boat.

On the other side of Rick is Victor Laszlo, the heroic resistance fighter. Rick admires him, but isn’t going to help him, even though Louis has announced his impending arrest in Rick’s café. In addition to his avowed detachment, Rick has another reason not to help Laszlo—turns out he’s married to Ilsa, the woman Rick believes betrayed him.

What Casablanca is really about, then, is how Rick gets to the decision not just to help Laszlo and Ilsa, but even to sacrifice his life (potentially) to do it. And in the famous ending twist, Rick’s moral reformation inspires Louis to make a similar choice. It’s “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Hold that thought.

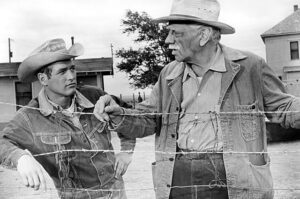

The other night I watched the Paul Newman film, Hud (1963). This superb movie (based on Larry McMurtry’s novel Horseman, Pass By) won three well-deserved Academy Awards: Best Actress (Patricia Neal); Best Supporting Actor (Melvyn Douglas); and Best Cinematography (James Wong Howe). The protagonist is Lon Bannon. He lives on a modest cattle ranch with his Granddad and uncle, Hud, and Alma, their housekeeper.

Lon has just turned seventeen. He’s on the cusp of adulthood. And he’s offered two paths. The first is from his beloved Granddad, who has built his entire life on working hard and doing what’s right and honest. The other is from Hud, whom Lon admires for his way with women and ease at being a “good ol’ boy.” As Hud explains to Lon, “When I was your age, I couldn’t get enough of anything.” Lon is increasingly leaning in Hud’s direction.

Then tragedy strikes the ranch. A herd of cattle Granddad recently brought in from Mexico has foot-and-mouth disease. All of the cows have to socially distance be exterminated. Hud tries to convince his father to sell off the bad cows to unsuspecting neighbors. Granddad, of course, will have none of it. “You’re an unprincipled man, Hud,” he says.

“Don’t let that fuss you,” Hud snaps back. “You’ve got enough for both of us.” Indeed, deep down, Hud would like nothing better than for Granddad to kick the bucket so Hud can take his half of the ranch and do what he pleases with it.

Once again, the mirror moment happens in the middle of the film. Lon and Granddad have gone to a movie together and are having a bite to eat at a diner. Hud comes stumbling in with a woman—another man’s wife. There’s a tense exchange between Hud and Granddad, who clasps his chest and keels over. Hud and Lon get him into a pickup truck and drive him back to the ranch. As Granddad sleeps between them, Lon says:

LON: He’s beginning to look kind of worn out, isn’t he? Sometimes I forget how old he is. Guess I just don’t want to think about it.

HUD: It’s time you started.

LON: I know he’s gonna die someday. I know that much.

HUD: He is.

LON: Makes me feel like somebody dumped me into a cold river.

HUD: Happens to everybody. Horses, dogs, men. Nobody gets out of life alive.

That “dumped into a cold river” is Lon’s awakening to the stakes. He’s going to have to make a decision on how to live life once Granddad is gone.

Two plot points happen that turn Lon away from Hud. First is Hud’s attempted rape of Alma, which Lon breaks up. Alma has been through the grinder of life, and Lon considers her good and kind. Seeing what Hud tries to do to her disgusts him.

The second point is when Lon and Hud are driving back to the ranch from a carouse in town and find Garnddad crawling on the road. He’d fallen off his horse, and is in bad shape. Lon cradles his head, tells him to hang on, that everything will be all right. Granddad says, “I don’t know if I want it to be.” He looks over at Hud. “Hud’s here waitin’ on me. And he ain’t a patient man.” With that he gives up the ghost.

Hud’s ill treatment of Granddad is the final straw for Lon. He decides to pack up and leave, not quite sure where he’ll end up. Hud makes one last pitch for Lon to stay on.

HUD: I guess you’ve come to be of your granddaddy’s opinion that I ain’t fit to live with. That’s too bad. We might’ve whooped it up some. That’s the way you used to want it.

LON: I used to. So long, Hud.

Lon walks away. Hud goes into the ranch house and grabs a beer from the icebox. He returns to the door to look at his departing nephew. Then, with a dismissive wave, he shuts the door.

That’s the end. Hud is all alone. No one to love him, no one for him to love. In this instance, contrary to Casablanca, the immoral character does not change, and we are shown the tragedy of that choice.

So consider setting your Lead between two characters who represent opposites on the moral scale. This will deepen the Lead’s dilemma and the story as a whole.

Comments welcome.

I just looked at the midpoint of the WIP. My character is faced with a choice, although he doesn’t make it at this point in the book. It would be life-changing, but there are no moral dilemmas for him, beyond having to consider his new wife’s side of the decision.

I’m thinking the last two books I’ve written have been “conflict-light” and I blame it on the current world situation. I just can’t dump a lot of bad stuff on my characters.

LOL, Terry. I know the feeling. We want to be nice. We hate to cause trouble. Problem is, “trouble is our business” in fiction.

Just a note. At the mirror moment the character doesn’t have to (and usually doesn’t) MAKE the big decision. That will be forced later.

Oh, there is plenty of conflict. And dead bodies. But things are resolved more easily than in the previous books. I’ll probably push the cozy side of my genre blend for this one.

If a main character doesn’t have conflict and a problem to solve, he doesn’t grow as a character or earn his happy ending. That’s very unsatisfying for a reader.

Even in romances, there must be conflict, and I’m not talking about the evil other woman trying to take the guy away from the sweet heroine. I’m talking inner conflict which usually has an outer component to it. As a writer, you figure out the inner conflict for your growth character/s, then attack it through the plot and the romantic characters interactions. Until the growth character/s can understand that inner conflict and weakness then move past it to become a better person and worthy of the other character’s love, there can be no happy ending for them or the reader.

Oh, he has plenty of problems to solve. But he’s not stuck with the same kind of moral dilemmas that JSB pointed out in his post.

My current manuscript is conflict-light, and what you’ve suggested is the perfect idea. Thanks, James!

Hi Carolyn. Here’s another use of “conflict-light.” If this post helps in that regard, I’m gratified.

Conflict-light—or what I call “too nice” syndrome. That’s something I really have to watch for in my writing.

In the Hud movie example, while reading the description about Hud being perfectly willing to sell diseased cattle to neighbors—I was appalled and thinking “how could anyone even take a notion to do such a horrible thing?” Thankfully the author and/or scriptwriter knew that “too nice” wouldn’t work. Good lesson for a writer to learn.

I think the same dynamic worked on the original Star Trek. Kirk stood out as a more relatable character, occupying the middle ground between the logical Mr. Spock and the ornery Dr. McCoy.

Excellent point, Mike. I’m not a Trekkie, but I believe I’ve seen some analysis of the show based on Jungian archetypes. Whether this was deliberate by the writers, or merely the consequence of good fiction craft (i.e., oppositional characters) I don’t know. But it certainly worked.

Kirk, Spock, and McCoy are a character trinity. When a problem needed to be solved, Spock was the logical mind, McCoy the emotional heart, and Kirk took both sides and created the ideal action.

These characters can also be considered a thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Two opposite sides of a problem from Spock and McCoy, and Kirk pulling both together to find the solution.

Character trinities are a great storytelling tool, particularly in a series.

And the episode “Galileo 7” is a very strong example of pitting the character against two opposites. Spock, commanding his first away mission, McCoy and several others on the landing party were so nasty to Spock I wanted to knock them into the middle of next week. The only person on that away mission who was reasonably decent to him was Scotty. But Spock needed to be pushed and it led to an awesome episode ending (one of my favorites).

That was one of my favorites, too. I had the same reaction to the characters relentlessly slamming Spock.

I’m stirring up ideas for my next story, and I want multiple conflicts. Your post is helpful, thanks!

Multiple conflicts! Now you’re talking fiction!

Great post, JIm. This puts more meat on the bone of the mirror moment tension. I came away from my original study of the mirror moment thinking only of two choices for the protagonist’s course of action. This is a great way to show, don’t tell. Two choices, two courses of action, two characters to learn from or choose to side with, two paths, and two outcomes. Two to the fourth power. A fourth dimension. Love it!

Thanks for continuing to add to our writer’s tool kit.

Thanks for the good word, Steve. Happy Sunday to you!

Jim, great discussion of moral dilemmas. They are the underpinning of classics like Casablanca and Hud and many more.

Somehow, though, moral dilemmas seem to be missing or ignored in a lot of contemporary bestselling fiction. So many characters are amoral, it’s hard to find anyone to root for. Sigh.

Guess that’s why I keep going back to the oldies.

I’m with you, Debbie. No amorality for me. I watched a recent thriller which was classic revenge-vigilante (i.e., yet another riff on Death Wish). Only in this one the protag goes to extremes, in one case torturing one of the bad guys before disposing of him. I immediately thought of the scene in Taken (a favorite) where Neeson uses torture in one scene…but to get essential information to find his daughter, not just to extend agony before dispatch. I can take the latter but not the former.

Hi Jim, such an insightful post. The mirror moment is such an important tool in my writers tool chest, this brings it to a whole new level. Like Terry above, I’m thinking about my current WIP, my library mystery.

I’m closing on the midpoint in fact, the moment when a library colleague is accused of murder. My hero has never solved a mystery before–can she? Can she really out sleuth the police? Mind you, this is a cozy, but it’s a great moment. And your post today made me realize I have two people in the novel who represent opposite sides of that, one being a young detective, and that I need to bring him in as a library patron early in the novel, as opposed to when the second death happens.

Thank you! Have a great Sunday.

Great insight, Dale. And your mirror moment sounds perfect for a cozy. Indeed, in a series where we know the sleuth is going to solve things, that mirror moment in each book needs to be the kind that challenges the character with “professional death.” The odds are greater than I’ve ever faced! If I fail to figure this out, might as well pack it in a sleuth of any kind. etc.

Jim, I read your great craft book “Write Your Novel From the Middle” as I was working on my second novel. I understood immediately how it could improve the story. After my protagonist is attacked by an unknown assailant because she’s trying to prove the innocence of a friend, she finds herself standing in front of a mirror, examining her bruises and wondering if it’s all worth it. That was the pivotal point of the book, and it forced the character to face the consequences of trying to do good or giving in to the temptation of safety. She knows she has to choose.

So thank you! My book was released in September and it’s doing well. I’m working on book number three now, and I have a good idea for another mirror moment. (Maybe this time I won’t use an actual mirror, though.? )

I’ll be on the treadmill later today. I’ve seen Casablanca a bunch of times, but I never saw Hud. Maybe I’ll catch it today.

Thanks, Kay. Hud is a great movie. I love the original tagline for the film, on the poster: Hud, the man with the barbed-wire soul.

Glad to hear your book is doing well and that the mirror moment has helped!

Hi Kay! Just downloaded both of your Watch series books. Can’t wait to dive in… 🙂

Thank you, Deb! What a delightful surprise on a sunny Sunday morning.

Right back at ya — downloading Who Are These People? I love the impact of minor characters!

??

Thanks, JSB! Got a question: the characters you speak of putting the MC between…must they be human? Not talking aliens here, but, say weather, or a bear, or a long-held fear.

In my two current projects, I do use a massive storm and a bear attack to illustrate the storm taking place within the main human characters; and in the other one, my MC must go head-to-head with a fear she’s tried to bury for decades.

Thanks!

Interesting question, Deb. My first reaction is that you don’t NEED to have these polar opposite characters. It’s just a device to deepen the moral dilemma for the Lead. You certainly can test your Lead by throwing in fear or bears or lions or tigers (oh my!). But I think what I’m talking about here needs human characters because a) they have the capacity to exert moral influence; and b) they have the capacity to change.

Got it! Thanks… 🙂

Never even heard of the movie Hud till you mentioned it, but just from reading your description of the movie, I want to rewrite the ending of the film & be the one to beat Hud to a pulp in the final climactic scene. 😎

I like this concept of pitting the leading between 2 opposing forces. Sounds like a good Sunday brainstorming session just thinking about possible stories that might utilize this.

LOL, BK. Hud has consigned himself to solitary confinement, a punishment worse than a beat down. Classic tragedy.

You bring up a good point, BK. Just brainstorming about this helps you think more deeply about the story. Always a good thing!

HUD works as it does because Lon is a kid so the two sides for him to choose don’t make him being a passive character a problem. If Lon were as old as Hud, he would be a boring and weak-willed main character.

For adult viewpoint characters, the good and bad characters on either side of the issue don’t necessarily have to be actively recruiting him. They can be representative to the reader of the character’s path as well as the worldbuilding of the novel at large. CASABLANCA uses this technique because the main issue in the movie isn’t Rick’s romantic choice, but the world falling apart because of the Nazis. The romantic choice just represents the two sides of the world.

Even more, Casablanca represents the two sides of a human being in a moral world. With or without a war, it demands a choice. That’s why William Foster-Harris defined fiction as a “problem in moral arithmetic.” Two values oppose, and one must prevail. If it’s the wrong one, you have tragedy. etc.

I’d be interested in hearing your take on the John Wayne character in John Ford’s “The Searchers.” (Love this movie for many reasons). Ethan (Wayne) spends five years on an obsessive quest to find his niece Debbie, the lone survivor of an Indian raid. When they finally find her, she’s living as the “wife” of Scar. This leads Ethan to say he has to kill her because she’s now “the leavin’s of a Comanche buck.” Martin has to shoot Ethan to stop him and Debbie escapes. The hunt continues. Yet in the climax, when Debbie is running away from Ethan, he scoops her up onto his horse and gallops away. Debbie is reunited with her family. The last great shot of the movie is The Wayne character silhouetted, alone, outside the family home.

I guess Wayne is a classic anti-hero. I don’t remember a particular “man in the mirror” moment since I haven’t seen the film in a long time. But it obviously has stuck with me!

Yeah, The Searchers sticks with a lot of people. I’ve not seen it in quite some time, so I don’t know what I’d say. Next time I watch, I’ll analyze.

Yes, Ethan is a classic anti-hero. He comes from out of the great lonesome and is pulled into a conflict. At the end, he does not return to the community, but goes out to the big lonesome again. That last shot is a mirror of the first shot. So I’m sure there’s a mirror in the middle!

Such a great refresher for us all, Jim. Thank you! I’m working on a series bible while writing the next book in the series, and I’m amazed by how badly I’ve abused this particular protagonist. Poor woman. As I’m listing her scars, emotional & physical, I *almost* feel bad. Almost. 😉

Hope you’re enjoying football Sunday!

So glad to hear how maliciously you have treated your protagonist, Sue! That, in a nutshell, is what fiction is all about. Without the “abuse,” there’s no need for strength of will, which is the engine of plot. I can hear your engines like at the Indy 500.

Thanks, Jim. Appreciate this reminder as I’m working on my current WIP. Definitely need more conflict in the middle.

We all do! Crank up the heat.

I’m a fan of write/novel/middle as I’ve often tweeted. Giggled about your socially distant cows & Garnddad crawling on the road. Is this a test?

Ha. You passed!

Thanks for another thought-provoking post, Jim. It made me break out a record I haven’t listened to in decades, that being Stealers Wheel. You know why.

LOL. I’m stuck there with you, Joe!

Pingback: Top Picks Thursday! For Writers & Readers 12-10-2020 | The Author Chronicles