by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

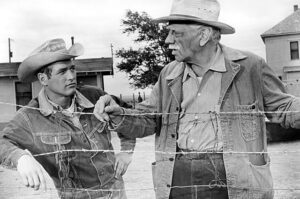

Jackie Gleason, Paul Newman in The Hustler (1961)

When I teach at a writers conference I’ll often show a clip from one of my favorite movies, The Hustler (1961), starring Paul Newman, George C. Scott, Piper Laurie, and Jackie Gleason. It’s the story of “Fast Eddie” Felson (Newman), a pool hustler who longs to beat the best player in the world, Minnesota Fats (Gleason).

Stuff happens (this is what’s called a short synopsis). Bert Gordon (Scott), who manages Fats, labels Eddie “a loser.” This gets under Eddie’s skin. One day he asks his girl, Sarah, if she thinks he’s a loser. She is taken aback. He says he lost control the night he went hustling and got mad at the arrogant kid he was playing. “I just had to show those creeps and those punks what the game it like when it’s great, when it’s really great.” He explains that anything, even bricklaying, can be great if “a guy knows how to pull it off.” He tells Sarah what he feels “when I’m really going.”

It’s like a jockey must feel. He’s sittin’ on his horse, he’s got all that speed and that power underneath him, he’s comin’ into the stretch, the pressure’s on ’im, and he knows! He just feels when to let it go and how much. ’Cause he’s got everything workin’ for him, timing, touch…it’s a great feeling, boy, it’s a real great feeling when you’re right and you know you’re right. It’s like all of a sudden I got oil in my arm. The pool cue’s part of me. You know, it’s a pool cue, it’s got nerves in it. It’s a piece of wood, it’s got nerves in it. You feel the roll of those balls, you don’t have to look, you just know. You make shots nobody’s ever made before. I can play that game the way nobody’s ever played it before.

Sarah looks at him and says, “You’re not a loser, Eddie, you’re a winner. Some men never get to feel that way about anything.”

Give thanks you’re a writer. We experience life in all its colors—joy, doubts, hopes, frustrations, wins, losses, knockdowns and comebacks. We work at our craft and get better, and start to make “shots” we’ve never made before. A writer of any genre can make a book great—from pulp to literary, romance to thriller, chicklit to hardboiled. And when you pull it off, you feel like pool felt to Fast Eddie. That’s winning, because some people never feel that way about anything.

Some years ago I wrote a takeoff on Clement Clarke Moore’s famous poem, “The Night Before Christmas.” I offer it to you once more as we sign off for our annual two-week break. Heartfelt thanks to all of you for another great year here at TKZ!

’Twas the night before Christmas, and all through the room

’Twas the night before Christmas, and all through the room

Was a feeling of sadness, an aura of gloom.

The entire critique group was ready to freak,

For all had rejections within the past week.

An agent told Stacey her writing was boring,

Another said Allison’s book left him snoring.

From Simon & Schuster Melissa got NO.

And betas agreed Arthur’s pacing was slow.

“Try plumbing,” a black-hearted agent told Todd,

And Richard’s own mother said he was a fraud.

So all ’round that room in a condo suburban

Sat writers––some crying, some knocking back bourbon.

When out in the hall there arose such a clatter,

That Heather jumped up to see what was the matter.

She threw the door open and stuck out her head

And saw there a fat man with white beard, who said,

“Is this the critique group that I’ve heard bemoaning?

That keeps up incessant and ill-tempered groaning?

If so, let me in, and do not look so haughty.

You don’t want your name on the list that’s marked Naughty!”

He was dressed all in red and he carried a sack.

As he pushed through the door he went on the attack:

“What the heck’s going on here? Why are you dejected?

Because you got criticized, hosed and rejected?

Well join the club! And take heart, I implore you,

And learn from the writers who suffered before you.

Like London and Chandler and Faulkner and Hammett,

Saroyan and King––they were all told to cram it.

And Grisham and Roberts, Baldacci and Steel:

They all got rejected, they all missed a deal.

But did they give up? Did they stew in their juices?

Or quit on their projects with flimsy excuses?”

“But Santa,” said Todd, with his voice upward ranging,

“You don’t understand how the industry’s changing!

There’s not enough slots! Lists are all in remission!

There’s too many writers, too much competition!

And if we self-publish that’s no guarantee

That readers will find us, or money we’ll see.

The system’s against us, it’s set up for losing!

Is it any surprise that we’re sobbing and boozing?”

“Oh no,” Santa said. “Your reaction is fitting.

So toss out your laptops and take up some knitting!

Don’t stick to the work like a Twain or a Dickens.

Move out to the country and start raising chickens!

But if you’re true writers, you’ll stop all this griping.

You’ll tamp down the doubting and ramp up the typing.

You’ll write out of love, out of dreams and desires,

From passions and joys, emotional fires!

You’ll dive into worlds, you’ll hang out with heroes.

You’ll live your lives deeply, you won’t end up zeroes!

And though you may whimper when frustration grinds you

There will come a day when an email finds you.

And it will say, ‘Hi there, I just love suspense,

And I found you on Kindle for ninety-nine cents.

I just had to tell you, the tension kept rising

And didn’t let up till the ending surprising!

You have added a fan, and just so you know,

If you keep writing books I’ll keep shelling out dough!’

So all of you cease with the angst and the sorrow,

And when you awaken to Christmas tomorrow,

Give thanks you’re a writer, for larger you live!

Now I’ve got to go, I’ve got presents to give.”

And laying a finger aside of his nose

And giving a nod, through the air vent he rose!

Outside in the courtyard he jumped on a sleigh

With eight reindeer waiting to take him away.

At the window they watched him, the writers, all seven,

As Santa and sleigh made a beeline toward Heaven.

But they heard him exclaim, ’ere he drove out of sight,

“Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good write!”

See you in 2026!