by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

When I teach workshops based on my book Write Your Novel From the Middle, I usually say that finding your “mirror moment” illuminates the entire book for you. It shows you what the story is really all about, from beginning to end––even if the novel is largely unwritten. So be ye planner or pantser, whenever you find your mirror moment, the path to your completed novel becomes a whole lot clearer.

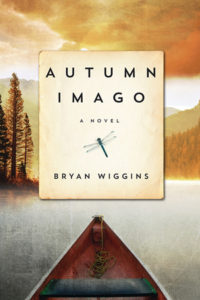

There’s another word to describe what’s going on, and it came to me in an email from writer Bryan Wiggins. Bryan is a serious student of the craft (via Brother Larry Brooks, myself and others). His novel, Autumn Imago, was recently selected as one of only three books to launch Harper Legend, a new imprint of Harper One, a member of the HarperCollins family.

There’s another word to describe what’s going on, and it came to me in an email from writer Bryan Wiggins. Bryan is a serious student of the craft (via Brother Larry Brooks, myself and others). His novel, Autumn Imago, was recently selected as one of only three books to launch Harper Legend, a new imprint of Harper One, a member of the HarperCollins family.

Bryan wrote:

In my story, my protagonist, Paul Strand, is a ranger in Maine’s remote Baxter State Park. Paul has turned his back on his nuclear family after it was shattered by the death of his sister, years before. Circumstances conspire to bring them to the park where Paul struggles between the isolation that has protected him from the wounds of the past and the intimacy that stands as his only chance for the healing that can make him whole. Paul battles those opposing forces throughout the book, but Middle provided me with a way to look at the central turning point in the story that helped me shape the “before and after” of his spiritual catharsis for maximum effect. That scene takes place during a rainstorm in a lean-to at the top of a mountain. There, Paul must decide whether or not to abandon his recovering addict-brother, or to give him the second chance that Paul doesn’t believe he deserves. The Mirror Moment helped me crystallize not only that crisis for Paul, but also helped me sharpen my larger narrative with the clear focus that helped earn the book a publishing contract with one of the “Big 5.”

I like that word, crystallize. It means to assume a definite shape. When Bryan’s character reached that decision point, he was looking at himself (as if in a mirror) and asking, What kind of person am I going to be? The shape of the story became discernable. That’s always a great feeling.

Bryan went on to say:

For a story structure freak like myself, one of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned is to simply surrender to the organic power of writing when the muse begins to sing. But as an analytical writer at heart, I’m always looking for a sharp instrument that I can also apply more directly to my work. Your book has proven to be such a tool.

I love story structure freaks. But I also tell writers that when they write they shouldn’t think about “rules” or “guidelines.” Just write! (“…simply surrender to the organic power…”) But then, afterward, put on the analytical hat. Fix what you can, learn how to fix what you can’t (via craft books, workshops, editors, teachers) and absorb. I always come back to the golf analogy. Don’t think of the 22 most important tips about your golf swing as you swing! Just play! Do your thinking after the round. And if you keep messing something up, go visit a teaching pro.

What will happen is this: you’ll get all those lessons into your “muscle memory,” and they’ll be there for you next time you play (or write!) Bryan went on in his email about writing the second book in his planned trilogy:

As I’ve been outlining, free-writing, and scene-writing my way to the middle of this sequel, I’ve been conscious again of “the magical midpoint moment” of my tale that Middle illustrates. My goal in this novel is to craft a character who demonstrates the drive for success meant to resonate with my readers, but to also show how that force can corrode the compassion for others that should always temper such ambition. Middle has again pointed to a critical mid-manuscript turning point between two opposing forces in my story. In this case, it’s a critical choice Wolf must make about whether or not to propose marriage to his lifelong friend (the girl next door) not for love, but to advance his career. As Middle suggests, that vantage point is providing me not only with one of the big, dramatic beats of my plot, but a perspective for tuning the entire thrust of my story before and after that point for maximum dramatic effect.

Let me add that if you know you’re writing a trilogy, you can have mirror moments for each book, and one for the entire series. There are mirror moments in each of the Hunger Games books, and one big one for the trilogy (hint: it involves Katniss’ inner argument about whether to bring a child into the world).

So I thank Bryan for his email, and the chance to share some of his writing process. You might also be interested in an early blog post by Bryan when he felt “lost” writing his first novel, and how he fought through. It’s called “Eighty Thousand Mistakes.”

To sum up about crystallizing your novel:

- When you write, write.

- At some point, brainstorm your mirror moment. It’s subject to change, of course, but I think you’ll find one that feels right. Let it be your guide.

- Visit the Lead’s pre-story psychology in light of the mirror moment. Flesh out the moral flaw. Why is it there? What happened in the Lead’s backstory that made him this way? (E.g., Rick at the beginning of Casablanca. Why doesn’t he stick his neck out for anybody? Because he was betrayed (he thinks) by the only woman he ever truly loved.)

- Brainstorm the transformation at the end (wherein the character overcomes the moral flaw, or has grown stronger). Come up with a visual that proves the transformation. (One of my favorites is in the film Lethal Weapon. Riggs is suicidal, has been carrying around a hollow-point bullet to blow his brains out. At the end, he shows up at Murtaugh’s house on Christmas and presents the bullet—with a ribbon on it—to Murtaugh’s daughter. “Give it to your dad, okay? It’s a present for him. Tell him I won’t be needing it anymore.”)

- Finish the novel, let it sit for a few weeks, then start the editing process. What you’ll find is that the issues you have in re-write are not with the central story, but in how you tell it. In other words, because you went to the mirror, the story will have a definite shape. It will be crystallized. Now smooth out edges, deepen characters, sharpen dialogue, tighten scenes.

Then let people read it. Then fix it some more.

This is called growing as a writer.

Which, as the Geico commercials say, is what you do!