In his book “On Writing,” Stephen King states he doesn’t read in order to “study the craft” but believes there is “a learning process going on” when he reads. Do you read books differently as a writer? Are you conscious of “the craft” as you read?

Yesterday, Joe Moore had an excellent post “Tips for Pacing Your Novel.” It made me think of subplots and story arcs that are other tools to punch up a story line with pace while the main plot enjoys a much needed rest for character development.

In a story arc, whether it is the arc of a romantic relationship or the personal journey of your main character, it might help you think of the arc using these key points:

5 Key Movements in a Story Arc:

1. Present State

2. Something Happens

3. Stakes Escalate

4. Moment of Truth

5. Resolve

Present State – Set the stage with the character or the relationship at the start of the story. This can also include a teaser of the conflict ahead or the characters’ problems that will be tested. If this is a thriller with a faster pace, you can start with a scene that I call a Defining Scene, where you show the reader who your character is in one defining moment of introduction. The reader can see who this character is by what he or she does in that enticing opener. Don’t tell the reader by the character’s introspection (internal monologue). Set the stage by his or her actions. These scenes take thought to pull together but they are worth it. Imagine how Capt. Jack Sparrow of Pirates of the Caribbean first steps onto the big screen. He wouldn’t simply walk on and deliver a line. He’d make a splash that would give insight into who he is and will be.

Something Happens – An instigating incident forces a change in direction and a point of no return. Your character and/or relationship often will move into uncharted territory that will test their resolve. Sometimes you can set up a series of nudges for the character to reject, but in the end, something must happen to shove him or her over the edge and into the main plot.

Stakes Escalate – in a series of events, test the characters’ problem or the relationship in a way that forces a conflict where a tough choice must be made. Make your character/couple earn the right to play a starring role in your novel. Don’t forget that this is not simply the main action of the plot or a conflict with the bad guys. This can also mean escalating the stakes of the relationship by forcing them into uncomfortable territory.

Moment of Truth – When push comes to shove, give your character or couple a moment of truth. Do they choose redemption or stay the course of their lives? When the stakes are the highest, what will your character do? I often think of this moment as a type of “death.” The character must decide whether to let the past die or a part of their nature die in order to move on. Do they do what’s safe or do they take a leap into something new?

Resolve – Conclude the journey or foreshadow what the future holds to bring the story full circle. I love it when there is a sense of a character coming through a long dark tunnel where they step into the light. A character or couple don’t have to be the same or restored in the end. Make the journey realistic. If a character survives, they are more than likely changed forever. What would than mean for your character? How will they be changed?

Apply this arc structure to individual characters or to a romantic love interest between two characters. These arcs are woven into the tapestry of your overall plot. The plot can be full of action and have its own arc, but don’t forget to add depth and layering to your story by making the characters have their own personal journeys.

Characters have external plot involvements (ie the action of the story), but they can also have their internal conflicts that often make the story more memorable. As an example of this, in the Die Hard movies, we may forget the similar plots to the individual movies, but what make the films more memorable is the personal stories of John McClain and his family. These personal arcs are important and need a structured journey through the story line. They can ebb and flow to affect pace. Escalate a personal relationship during a time when the main plot is slowing down. Make readers turn the pages because they care what happens to your characters.

For Discussion:

Share your current WIP, TKZers. How do you integrate your main character’s personal journey into the overall plot? Share a bit of your character and how his or her “issues” play into your story line.

The story in most novels takes place over a period of time. Some are condensed to a few hours while many epic tales span generations and perhaps hundreds of years. But no matter what the timeframe is in your story, you control the pacing. You can construct a scene that contains a great amount of detail with time broken down into each minute or  even second. The next scene might be used to move the story forward days, weeks or months in a single pass. If you choose to change-up your pacing for a particular scene, make sure you’re doing it for a solid reason such as to slow the story down or speed it up. Remember that as the author, you’re in charge of the pacing. And the way to do it is in a transparent fashion that maintains the reader’s interest. Here are a couple of methods and reasons for changing the pace of your story.

even second. The next scene might be used to move the story forward days, weeks or months in a single pass. If you choose to change-up your pacing for a particular scene, make sure you’re doing it for a solid reason such as to slow the story down or speed it up. Remember that as the author, you’re in charge of the pacing. And the way to do it is in a transparent fashion that maintains the reader’s interest. Here are a couple of methods and reasons for changing the pace of your story.

Slow things down when you want to place emphasis on a particular event. In doing so, the reader naturally senses that the slower pace means there’s a great deal of importance in the information being imparted. And in many respects, the character(s) should sense it, too.

Another reason to slow the pacing is to give your readers a chance to catch their breath after an action or dramatic chapter or scene. Even on a real rollercoaster ride, there are moments when the car must climb to a higher level in order to take the thrill seeker back down the next exciting portion of the attraction. You may want to slow the pacing after a dramatic event so the reader has a break and the plot can start the process of building to the next peak of excitement or emotion. After all, an amusement ride that only goes up or down, or worse, stays level, would be either boring or frantic. The same goes for your story.

Another reason to slow the pace is to deal with emotions. Perhaps it’s a romantic love scene or one of deep internal reflection. Neither one would be appropriate if written with the same rapid-fire pacing of a car chase or shootout.

You might also want to slow the pacing during scenes of extreme drama. In real life, we often hear of a witness or victim of an accident describing it as if time slowed to a crawl and everything seemed to move in slow motion. The same technique can be used to describe a dramatic event in your book. Slow down and concentrate on each detail to enhance the drama.

What you want to avoid is to slow the scene beyond reason. One mistake new writers make is to slow the pacing of a dramatic scene, then somewhere in the middle throw in a flashback or a recalling of a previous event in the character’s life. In the middle of a head-on collision, no one stops to ponder a memory from childhood. Slow things down for a reason. The best reason is to enhance the drama.

A big element in controlling pacing is narration. Narrative always slows things down. It can be used quite effectively to do so or it can become boring and cumbersome. The former is always the choice.

When you intentionally slow the pace of your story, it doesn’t mean that you want to stretch out every action in every scene. It means that you want to take the time to embrace each detail and make it move the story forward. This involves skill, instinct and craft. Leave in the important stuff and delete the rest.

There will always be stretches of long, desolate road in every story. By that I figuratively mean mundane stretches of time or distance where nothing really happens. Control your pacing by transitioning past these quickly. If there’s nothing there to build character or forward the plot, get past it with some sort of transition. Never bore the reader or cause them to skip over portions of the story. Remember that every word must mean something to the tale. The reader assumes that every word in your book must be important or you wouldn’t have written it.

We’ve talked about slowing the pacing. How about when to speed it up?

Unlike narration, dialog can be used to speed things up. It gives the feeling that the pace is moving quickly. And the leaner the dialog is written, the quicker the pacing appears.

Action scenes usually call for a quicker pace. Short sentences and paragraphs with crisp clean prose will make the reader’s eyes fly across the page. That equates to fast pacing in the reader’s mind. Action verbs that have a hard edge help move the pace along. Also using sentence fragments will accelerate pacing.

Short chapters give the feeling of fast pacing whereas chapters filled with lengthy blocks of prose will slow the eye and the pace. Make sure you write it that way for a reason.

Just like the pace car at the Indianapolis 500 sets the pace for the start of the race and dramatic changes during the event such as yellow and red flags, you control the pace of your story. Tools such as dialog versus narration, short staccato sentences versus thick, wordy paragraphs, and the treatment of action versus emotion puts you in control of how fast or slow the reader moves through your story. And just like the colors on a painter’s pallet, you should make use of all your pacing pallet tools to transparently control how fast or slow the reader moves through your story.

How about you Zoners? Got any hot tips on pacing?

I returned from an amazing trip to India all the more excited about possible future projects not just because my ‘on the ground’ research was more fruitful than I expected, but because I’d been able to experience that critical connection to history that will (I hope) provide the window I need to reimagine the past. I’d felt this connection once before, in Venezuela, and it provided me the impetus for writing my first Ursula Marlow mystery, Consequences of Sin.

I returned from an amazing trip to India all the more excited about possible future projects not just because my ‘on the ground’ research was more fruitful than I expected, but because I’d been able to experience that critical connection to history that will (I hope) provide the window I need to reimagine the past. I’d felt this connection once before, in Venezuela, and it provided me the impetus for writing my first Ursula Marlow mystery, Consequences of Sin.

For a historical mystery writer, I need to feel a connection to the history I’m writing about. I want to convey the sensory experience of what it would have been like to live in another era and for that I need some means of accessing the past on a personal level to enable the true ‘reimagining’ process to begin. This is easy for me in a place like England where family ties already establish that connection, but much harder when I consider other places and eras to which I have little in the way of understanding or connection.

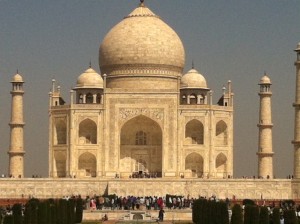

I wasn’t sure what I’d find on my trip to India (apart from obviously some very beautiful places – see the photo of the Taj Mahal above – which is awe-inspiring – and the sharp contrast between poverty and luxury – also evident in Agra just streets away from the Taj Mahal). I certainly wasn’t sure what my reaction would be to the place or its history.

As it turned out, I was surprised how easily I felt an affinity to those Europeans who arrived in India during the late 18th and early 19th centuries (the period that I had, not surprisingly, been researching with a future novel in mind). Although many historical places were difficult to isolate against the noise, traffic and bustle of modern life in India, I had no trouble reimagining what it must have once been like. I also found that I was beginning to inhabit the mind and imagination of some of the characters I had begun to sketch out in my head before my trip, and so much of what I saw, smelled, and heard could be accessed through the prism of their thoughts and background, not just my own.

One of the most surprisingly things to come out of my research was that the place I had originally believed would be the initial setting for my story (Hyderabad) was totally displaced by my experiences in another city (Udaipur – photo to the right) and I saw quite clearly my characters inhabiting this landscape and not the one I had previously envisaged (only downside, a whole new set of history books to read!).

One of the most surprisingly things to come out of my research was that the place I had originally believed would be the initial setting for my story (Hyderabad) was totally displaced by my experiences in another city (Udaipur – photo to the right) and I saw quite clearly my characters inhabiting this landscape and not the one I had previously envisaged (only downside, a whole new set of history books to read!).

One of the best things about travel is that it rarely provides the experience you expect – and it’s in the unexpected that I find the greatest inspiration.

So now I’m back, I just need to get down to the business of actually writing. In the meantime, I’d love to hear some TKZers’ unexpected travel and research experiences – how have they inspired your writing?

10. Characters are how readers connect to story

10. Characters are how readers connect to story

I’ve read books about the history of eras, and while interesting, they are nothing compared to a good biography (I’m currently reading H. W. Brands’ biography of Andrew Jackson). Why? Because we are more fascinated with people than epochs. (I once heard history described as “biography on a timeline.”)

We all love twisty turny plots, chases, love, hate, fights, freefalls––all of that. But unless readers connect to character first, none of that matters.

9. On the other hand, character without plot is a blob of glup

Contrary to what some believe, a novel is not “all about character.” To prove the point, let’s think about Scarlett O’Hara. Do you want 400 pages of Scarlett sitting on her front porch, flirting? Going to parties and throwing hissy fits? I didn’t think so. What is it that makes us keep watching Scarlett? A little thing called the Civil War.

A novel is not a story until a character is forced to show strength of will against the complications of plot. Plot brings out true character, rips off the mask, and that’s what readers really want to see.

“Blob of glup,” by the way, is a term I remember from my mom reading me The Thirteen Clocks by James Thurber. I always thought it quite descriptive.

8. Lead characters don’t have to be morally good, just good at something

Two of the most popular books in our language are about negative characters. I define a negative character as one who is doing things that the community (theirs, and ours) do not approve of, that harm other people. A Christmas Carol has Scrooge, and Gone With the Wind has Scarlett. Why would a reader want to follow them?

Two reasons: They want to see them redeemed, or they want to see them get their “just desserts.”

The trick to rendering a negative Lead is to show, early, a capacity for change. When Scrooge is taken back to his boyhood, we see in him, for the first time, some compassionate emotion. Maybe he’s not a lost cause after all!

Or show that the negative character has strength, which could be an asset if put to good use. Scarlett has grit and determination (fueled by her selfishness) and just dang well gets things done. We admire that, and hope by the end of the book she’ll turn it to something that actually helps those in her world. She does, but by then it’s too late. Rhett just doesn’t give a damn.

7. Characters need backstory before readers do

Yes, you have to know your character’s biography, at least the high points. One question I like to ask is what happened to the character at sixteen? That’s a pivotal, shaping year (unless your character actually is sixteen, in which case I’d go to age eight).

But you don’t have to reveal all the key information to readers up front. In fact, it’s good to withhold it, especially a secret or a wound. Show the character behaving in a way that hints at something from the past, currents below the surface. Why does Rick in Casablanca stick his neck out for nobody? Why does he play chess alone? Why doesn’t he protect Ugarte? Why doesn’t he love Paris? We see him act in accord with these mysteries, and don’t get answers until well into the film.

6. But readers want to know a little something about the character they’re following

Against the advice that you should have absolutely zero backstory in the first fifty pages, I say do what Stephen King, Dean Koontz, Michael Connelly and most every bestselling novelist does: sprinkle in bits of backstory in the opening pages. But only what is necessary to help readers bond to character.

A rule of thumb I give in my workshops is this: In the first ten pages, you can have three sentences of backstory, used all together or spread out. In the next ten pages, you can have three paragraphs of backstory, used all together or spaced out. This will force you to examine closely what you include, saving the rest for later, and letting the story get cracking.

5. Memorable characters create cross-currents of emotion in the reader

We all know about inner conflict. A character is unsure about what he’s about to do, and there’s an argument in his heart and soul, giving him reasons both for and against the action. That’s good stuff, and one way to get there is to identify the fear a character feels in each scene.

But to create even greater cross-currents of emotion in the reader, consider having the character do something the absolute reverse of what the reader expects. Brainstorm ideas for this, and you’ll often find a great one down the list, beyond your predictability meter. Put that action in. Write it. Have other characters react to it.

Only then find a way to justify the behavior, and work that into your material.

It was E. M. Forster, in Aspects of the Novel, who defined “round” (as opposed to “flat”) characters as those who are “capable of surprising us in a convincing way.”

4. Great villains are justified, at least to themselves

The antagonist (or as I like to put it, the Opponent) is someone who is dedicated to stopping the Lead. It does not have to be a villain, or “bad guy.” It just has to be someone on the other side of one definition of plot: two dogs and one bone.

When you do have a bad guy opponent, don’t fall into the trap of painting him with only one color. The pure-evil villain is boring and manipulative, and readers won’t fall for it. You’re also robbing them of a deeper reading experience (for which they’ll thank you by looking for your next book).

One exercise I give in workshops is the opponent’s closing argument. Pretend they have to address a jury and justify their actions. They are not going to argue, “Because I’m just a bad guy. I’m a psycho. I was born this way!” No bad guy thinks he’s bad. He thinks he’s right.

Make that argument. Weave the results into your book.

3. Don’t waste your minor characters

One of the biggest mistakes I see new writers make is putting stock characters into minor roles: The burly bartender, wiping glasses behind the bar; the boot-wearing, cowboy-hat-sporting, redneck truck driver; the saucy, wise-cracking waitress.

Instead, give each minor character something to set him or her apart from the stereotype. Think of:

• Going against type (a female truck driver, for example)

• An odd tick or quirk

• A distinct speaking style

Use minor characters as allies or irritants. Even those who have only one scene. A doorman, for example. Instead of his opening the door for your Lead, have him give the Lead a hard time. Or have your Lead in a hurry but the cab driver is lethargic and chatty.

A little time spent on spicing up minor characters will add mounds of reading pleasure to your readers.

2. Great characters delight us

When I ask people to name their favorite books or movies, and then ask why, it’s invariably because of one great character. As good as Harrison Ford is in The Fugitive, people always mention Tommy Lee Jones, and even his famous line, “I don’t care!”

The Silence of the Lambs? Two great characters. The absolutely unforgettable Hannibal Lecter, and the insecure but dogged trainee, Clarice Starling. Lecter delights us (because we are all a little twisted) with his wit, deviousness, and dietary habits. Clarice delights us because she’s the classic underdog who fights both professional and personal demons.

1. Great characters elevate us

Truly enduring characters end up teaching us something about humanity and, therefore, about ourselves. They elevate us. And that is true even if the character is tragic. As Aristotle pointed out long ago, the tragic character creates catharsis, a purging of the tragic flaw, thus making us better by subtraction.

On the positive side, I think of Harry Bosch and Atticus Finch, both on a seemingly impossible quest for justice. I’m the better for reading about them, and those are the kinds of books I always read more than once.

On the negative side, I think of the aforementioned Scarlett O’Hara. We are pulling for her to do the right thing, to get with it, to join the community of the good. Then she goes off an marries some other guy she doesn’t love and uses him mercilessly. When she finally suffers the consequences of her actions we, too, are duly warned.

So, TKZers, when you think of an unforgettable character, who comes to mind? What is it about this character that moves you? Elevates you? Makes you want more of the same?

True story: some college students were touring a county coroner’s office. The tour included visit to an autopsy room, where a coroner and a diener were in the process of examining the body of a deceased unfortunate. The diener, with the students looking on, turned the corpse over and exclaimed, “Rut row!” The reason for this utterance was that the corpse had a tattoo of Scooby Doo inked into one cheek of his posterior. Gallows humor, indeed.

Scooby Doo is firmly ensconced in the American culture. The plot of each cartoon episode is very similar, with a crime occurring, Scooby and his pals investigating, and the villain of the piece being unmasked, literally, at the end. I think that I

first heard this type of climax referenced as a “Scooby Doo” ending during the second of the three climaxes to the film Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. It has been a vehicle used in mystery novels long before that. There’s nothing wrong with it at all, except that 1) it sometimes doesn’t work and 2) sometimes it needs a little work. I ran across an example of the former several months ago while reading a thriller that was one of the many nephews to The Da Vinci Code wherein the protagonist’s adversary was running around killing people while wearing a tribal mask and attempting to obtain an instrument of antiquity which would permit him to destroy the universe. The protagonist got the mask off of the evildoer near the end and the book ended. “Rut row!” The book was okay, but the ending was a total disappointment.

That brings us to a book I read this week in which the author uses the Scooby Doo ending to great effect by taking the story a step or two beyond it. The author is the morbidly underappreciated Brian Freeman and the book is Season of Fear, the second and latest of the Cab Bolton novels. (Please note: it’s not quite a spoiler, but there’s a general revelation ahead. Read the book regardless). The premise is fairly straightforward. Ten years ago a Florida gubernatorial candidate was assassinated by a masked gunman, throwing the election into chaos. A suspect was identified, tried, convicted, and jailed. In the present, the candidate’s widow is running for the same seat when she receives a threatening note which purports to be from the same assassin. Indeed, he eventually turns up, and his identity is ultimately revealed in a grand unmasking. But wait. Freeman, after giving the reader enough action to fill two books and expertly presenting a complex but easy to follow plot, gives the reader more to chew on. Things don’t end with the revelation of the identity of the doer; instead, Freeman moves us a couple of more steps forward, revealing a potential unexpected mover and shaker who was a couple of steps ahead of everyone, including Bolton. This has the double-barreled effect of making the climax much more interesting and setting up a potential adversarial setting for Cab Bolton in a future novel. Nice work.

Again, Scooby Doo endings are okay. They’re fine. But if your particular novel in waiting has one, and seems to lack pizazz, don’t just take the doer’s mask off, or reveal their identity, or whatever. Take things a step further just as the curtain is going down, and reveal who is pulling the cord, and perhaps yanking the chain. It may be a character that was present throughout your book, or someone entirely new, or…well, you might even want to create a character and work your way backwards with them. But stay with the mask, and go beyond it.

So what say you? Have you read anything recently where the ending really surprised you, unmasking revelations or otherwise notwithstanding? Do you like Scooby Doo endings, in your own work or the work of others? Or can you do without them?

Oh, lest I forget… SCOOBY-DOO and all related characters and elements are trademarks of and © Hanna-Barbera. Rowwrr!

Some bookstores are mad as hell at writers, and for good reason.

We writers still need bookstores. Even self-published writers like to see their work displayed on store shelves – at least the ones I know.

And bookstores need to fill those shelves with our pretty books.

So why is it so hard to make this work?

I used to be a bookseller, and a couple of members of the tribe told me why writers’ books may not make it onto their shelves. I’m not using their names because they spoke bluntly about the issues.

Here’s what booksellers want you to do:

(1) Give me a real new release.

An independent bookstore owner said, “I’m not interested in mysteries that authors have been trying to sell on their own for six weeks, but are still calling new releases. When your book is first out, bring it to me.”

(2) Give me time to display your new release.

Make sure your books are at the store in plenty of time. Either hound your publisher or personally deliver the books to the store. “For an April 1 release, I’ll need to have a copy of the book in my store by March 25,” an indie bookseller said.

(3) It costs money to stock your books.

“Many traditional publishers are charging restocking fees now,” the indie bookseller said. “So if your books don’t sell, my store loses money. Self-published books require paperwork and have storage, pickup and delivery problems. I don’t have to the space to keep them.”

(4) A fact of book selling life: Some local authors don’t sell in my store.

The authors are charming. Their covers are good-looking. “But their books don’t sell. I’ve had some authors’ books for a year and no one bought them,” he said. The big box stores would have returned those books months ago.

“I can display your books as a new release for two or three weeks, but if they don’t sell, I can’t afford to give those books shelf space.” If this bookstore isn’t the right fit for your work, look for one that can sell your books.

(5) A bookstore is a place to buy books – not a showroom.

“I’ve had people buy the books on Amazon – Amazon!” he said. “Then these same people come to hear the author at my store, eat my snacks and drink my bottled water and soda. Can they do that on Amazon? No!

“I’ve watched people in the audience take out their e-readers or their iPhones during the talk and order from Amazon. That’s why booksellers are starting to charge for signings.

“Authors, if you have a signing at my store, please ask your friends and fans to buy the book here.”

(6) Avoid the A-word.

That’s Amazon. A Barnes & Noble community relations manager told me this story:

“A customer wanted a local author to speak and sign books for her group. I gave her the names of several people I thought would be a good fit for her organization. We spent half an hour discussing various authors, and then I gave her their contact information.

“ ‘Now,’ I said, ‘when you get the author, how many copies would you like to order for your event?’

“ ‘Oh, I’ll get the books from Amazon,’ she said. ‘They’re cheaper.’ ”

Win a free hardcover. I’m giving away my first Dead-End Job Mystery that was in hardcover, “Murder Unleashed.” Enter to win by clicking Contests at www.elaineviets.com

I can see colors fine except when I have to write them in a story. Then I’ll say a character has brown eyes, is wearing a green top with khakis, and has her nails painted red. What is wrong with this picture? Rainbow colors don’t do justice to the myriad of shades out there. So how do you get more specific? Here are some helpful aids. Think in categories.

Jewels—pearl, amethyst, emerald, ruby, sapphire, jade

Flowers—rose, lilac, daffodil, lavender

Food—grape, cherry, orange, lemon, lime, cocoa, coffee, fudge, chocolate, blueberry, avocado, strawberry

Minerals—onyx, copper, gold, silver, malachite, cobalt

Nature—slate gray like a thundercloud, leaf green, walnut, coal, ivory

But sometimes my mind goes blank, and so I turn to the most creative resource of all—a department store catalog. You can’t get any more imaginative than this, whether it’s towels or tops or sweaters. Here are some descriptive colors from a recent newspaper insert:

Heather gray, apple green, aquatic blue, berry, coral, cornflower blue, charcoal, navy, banana, raspberry, tropical turquoise, sky blue, stone gray, violet, burgundy, claret, evergreen, marine teal, sand, ocean aqua, pewter, snow.

You get the idea. And so I’ve created a file listing descriptive adjectives under each basic rainbow color. Here is one example:

BROWN

chestnut, auburn, mahogany, walnut, hazel, fawn, copper, camel, caramel, cinnamon, russet, tawny, sand, chocolate, maroon, tan, bronze, coffee, rust, earth, dusty, mud, toffee, cocoa

Thus when I am stuck for a particular shade, I can hop over to my color chart and pick one out.

Colors descriptions also convey emotions. For example, mud brown, toad green, or cyanotic blue have a less pleasant connotation than chocolate brown, sea green or ocean blue. So choose your hues carefully to enhance a scene.

What’s your secret to describing colors?

“It is easier to tone down a wild idea than to think up a new one.” — Alex Osborn

I don’t know how you guys do it. Those of you who write alone, I mean.

I am blessed in that I work with a co-author, my sister Kelly. Our collaboration began more than 20 years ago and has lasted through 20-some books (counting the ones that didn’t get published). And while we have had our disagreements over the years, we have always understood the power behind the notion that two brains are better than one.

I want to talk today about brainstorming.

This came about because I was cleaning out my computer folders the other day. I have one folder I labeled BRAIN LINT. This is just a depository for all the stuff I can’t find a good place for but am too gutless to throw out. In this folder are still-born story ideas, pictures cadged from iStock that were meant to inspire, old newspaper articles about bizarre crimes and weirdos, and one completed manuscript that is so bad I keep it just to remind myself of how far I have come and how far I could fall.

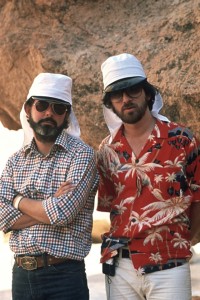

When I was cleaning out the lint, I found one gem. It is a transcript of a story conference in 1978 between Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Lawrence Kasdan. They were brainstorming about a possible movie. It didn’t have a title then, but it would eventually be made under the title Raiders of the Lost Ark. You might have heard of it.

Here’s just one exchange:

Lucas: We want to make a very believable character. We want him to be extremely good at what he does, as is the Clint Eastwood character or the James Bond character. James Bond and the man with no name were very good at what they did. They were very fast with a gun, they were very slick, they were very professional. They were Supermen.

Lucas: We want to make a very believable character. We want him to be extremely good at what he does, as is the Clint Eastwood character or the James Bond character. James Bond and the man with no name were very good at what they did. They were very fast with a gun, they were very slick, they were very professional. They were Supermen.

Kasdan: How do you see this guy?

Lucas: Someone like Harrison Ford, Paul LeMatt. A young Steve McQueen. It would be ideal if we could find some stunt man who could act.

Spielberg: Burt Reynolds. Baryshnikov.

Kasdan: Do you have a name for this person?

Lucas: I do for our leader.

Spielberg: I hate this, but go ahead.

Lucas: Indiana Smith. It has to be unique. It’s a character. Very Americana square. He was born in Indiana.

Kasdan: What does she call him, Indy?

I still can’t get the image of Baryshnikov in a fedora out of a mind. But that was how Indiana Jones was born, out of a brainstorming session between three creative guys. What a strange word – brainstorming. Ever wonder where it came from?

Well, in 1919, Alex Osborn, an ex-newspaper man from Buffalo, joined with Bruce Fairchild Barton and Roy Sarles Durstine to form the hugely successful BDO advertising agency. Osborn went on to write many books on creativity but he’s the one who coined the term “brainstorming.”

Well, in 1919, Alex Osborn, an ex-newspaper man from Buffalo, joined with Bruce Fairchild Barton and Roy Sarles Durstine to form the hugely successful BDO advertising agency. Osborn went on to write many books on creativity but he’s the one who coined the term “brainstorming.”

Nowadays, “brainstorming” is a catch-all for any type of creative group grope. But I thought it might be interesting to go back and see what Osborn had to say about it back in 1953 and find out if it could help writers today. Well, guess what? It’s still good advice, whether you are collaborating, working in a critique group — or even flying solo.

Here’s my main take-aways from Osborn’s ideas on brainstorming.

1. Think up as many ideas as possible regardless of how ridiculous they may seem. It’s unlikely you’ll get the perfect solution right off the bat, so he recommends getting every idea out of your head and then go back to examine them afterwards. An idea that may sound crazy may actually turn out to work with a little modification.

Doesn’t this make sense when you’re plotting? I know when Kelly and I talk, we throw everything on the wall. You need to take the same approach with yourself. Write down every idea and let them bake for a while. Sometimes, the most outrageous thing leads to something useful.

2. Don’t be judgmental. All ideas are considered legitimate and often the most far-fetched are the most fertile. Ideas can be evaluated after the brainstorming session but judgments during the process should be withheld.

Are you sometimes too hard on yourself? Do you think, “Oh, that’s so stupid, no editor will ever buy it.” Or maybe you are a self-doubter, telling yourself, “I don’t have the chops to try this technique.” Or: “This is a great idea but it’s so complex so I won’t even try.”

3. Go for quantity not quality. Don’t get hung up (like I often do) on coming up with the most clever solution to your writing problem. Let your brain waves flow so the bad stuff bobs up to the surface along with the good. Osborn said: “Creativity is so delicate a flower that praise tends to make it bloom while discouragement often nips it in the bud. Forget quality; aim to get a quantity of answers. When you’re through, your sheet of paper may be so full of ridiculous nonsense that you’ll be disgusted. Never mind. You’re loosening up your unfettered imagination—making your mind deliver.”

Osborn’s books were geared more toward corporate types trying to get their teams to think more creatively on things like how to get traffic flowing better in big cities. But take a look at his suggestions for improving creativity and see if there’s not something here for us mere writers:

1. Break up the problem into smaller pieces. For writers, this can mean tackling each plot or character problem as manageable bites, not getting overwhelmed by the idea that you’ve got 400 pages to fill. Get that first draft written then go back and fix your plot holes or layer your characters better.

2. Search for alternatives. If you’ve painted yourself into a plot corner, look for a different way out than the old ways.

3. What can be borrowed or adapted? Read other writers and learn from them.

4. Modify with new twists. There aren’t many new plots in crime fiction but there is always a way to put your own fresh imprint on them.

5. Is there something that can be magnified or minified? Maybe the stakes in your thriller aren’t high enough. Maybe you need to play down a secondary character who is overshadowing your hero. Are you larding in too much research?

6. What can be substituted? Maybe if you changed your location the story would suddenly come alive. Would your mystery work better in a small town where you could exploit the English village dynamic? Is your setting banal and underwritten? Are you hitting all the wrong clichés if your book is set in Paris or some other iconic place?

7. What can be re-arranged? Maybe you’re writing in the wrong point of view? Try switching from first to third. Or maybe the guy you think is your hero is really the bad guy?

8. Consider the vice versa. I love this one. Do just the opposite of what you are now doing. Is your protag male? Switch gender! Are you relying on tired character tropes (lonely alchoholic PI, sweet antique store owner who solves crime). Make your brain do a 180 and examine what is on the flip side. I did this with my latest book. The woman I thought was my protag turned out to be one of two in a dual-protag parallel theme story.

Okay, enough lessons. Let’s end by going back and eavesdropping some more on the Indiana Jones brainstorm session. CLICK HERE to read the whole thing.

Lucas and Spielberg started with the idea that they wanted to make a movie that was like old Republic serials of the Thirties (Zorro, Dick Tracy, Red Ryder). Something had to always kept happening, every ten minutes or so another cliff-hanger situation. From there, the guys dreamed up Indiana Smith and other elements. In the beginning, even the ark was just a MacGuffin.

Lucas and Spielberg started with the idea that they wanted to make a movie that was like old Republic serials of the Thirties (Zorro, Dick Tracy, Red Ryder). Something had to always kept happening, every ten minutes or so another cliff-hanger situation. From there, the guys dreamed up Indiana Smith and other elements. In the beginning, even the ark was just a MacGuffin.

Lucas: The thing is, if there is an object of antiquity, that a museum knows about that may be missing, or they know it’s somewhere. He can go like an archeologist, but it’s like rather than doing research, he goes in to get the gold.

Spielberg: His main adversaries will be the Germans?

Lucas: Yeah, I think they should be. I’ve been trying to move him around the world a little bit to see if we can’t get a little Oriental influence into it just for the fun of it. I may have fit it in. The fun thing is, he’s a soldier of fortune, so we can move him into any sort of exotic thirties environment we want to.

Spielberg: Keep him out of the States. We don’t want to do one shot in this country.

Lucas: The film starts in the jungle. South America, someplace. We get one of these great scenes with the pack animals going up the mist-covered hills. Very exotic mist-filled jungles and mountains.

Spielberg: Where he goes into the cave?

Lucas: This is where he goes into the cave. We had it where there’s a couple native bearers, whatever, and sort of a couple of Mexican, well not Mexican…

Spielberg: They’re like Mayan.

Lucas: They’re the third world local sleazes…[LATER] He goes into this very sleazy Casablanca type club and makes contact with this agent. The agent is a girl. She’s sort of a Marlene Dietrich tavern singer spy. A German lady singer. She’s really a double agent.

Lucas: They’re the third world local sleazes…[LATER] He goes into this very sleazy Casablanca type club and makes contact with this agent. The agent is a girl. She’s sort of a Marlene Dietrich tavern singer spy. A German lady singer. She’s really a double agent.

Spielberg: I like the idea that she’s a heavy drinker and our hero doesn’t drink at all. She gets drunk a lot. She’s beautiful and she gets really sexy when she’s drunk, and silly. And he doesn’t touch the stuff.

Lucas: I don’t want to soften her. I like the fact that it’s greed. I like all the hard stuff, but you’re going to love her.

Spielberg: There should be a real slimy German character. He’s the only gestapo involved there. Every time you see him, you know it’s going to be the worst pain, death by torture. This guy looks like a ferret. He’s got that slick black hair. His name is Himmler or something like that. He’s a stocky short guy, a master torturer.

Spielberg: There should be a real slimy German character. He’s the only gestapo involved there. Every time you see him, you know it’s going to be the worst pain, death by torture. This guy looks like a ferret. He’s got that slick black hair. His name is Himmler or something like that. He’s a stocky short guy, a master torturer.

Lucas: What can he chase them with? What if he jumps on a camel?

Spielberg: I love it. It’s a great idea. There’s never been a camel chase before.

Lucas: Is this camel going to chase a car?

Spielberg: You know how fast a camel can run? Not only that, he can jump over vegetable carts and things. We still have the big fight in the moving truck to do. And now we have a camel chase.

Lucas: We’ve added another million dollars.

Spielberg: Not really. How much trouble can a camel be?

And then they talk about the big scene toward the end where Indy and Marion are tossed into that deep tomb and the bad guys cover it up with a rock. They’re trying to figure out what is in the tomb that’s dangerous and how Indy gets out. They decide there is a huge artesian well that opens up and he and Marion are in danger of drowning. Then somebody suggests there are also wild animals in the tomb, like tigers.

Spielberg: It would have to be a neighborhood tiger.

Lucas: There aren’t any tigers out there.

Spielberg: I’m not in love with the idea.

Lucas: You could have bats and stuff, make it slightly spooky.

Spielberg: What about snakes? All these snakes come out.

Lucas: People hate snakes. Asps? They’re too small.

Spielberg: It’s like hundreds of thousands of snakes.

Lucas: When he first jumps down in the hole, it’s a giant snake pit. Then when he says they’re afraid of light, they throw down torches. You have a whole bunch of torches that keep the snakes back. So he only has one more torch, and the snakes start coming in. He sits there with one torch, knowing that when the torch goes out… It’s the idea of being in a room, in a black room with a lot of snakes. That will really be scary.

Spielberg: The snakes are waiting, looking at him. Thousands. And the torches are burning down. He’s trying to keep it going. The torch goes out. The whole screen goes black. The sound of the snakes gets more intense. You hear him backing up. The camera pans and suddenly you see, it’s black, but there’s light coming from several cracks. It’s not completely black. That leads him to an opening. To a rock that isn’t so flush against the other rocks. He knows there’s access. He keeps pushing on it, he gets a little more room.

Lucas: We shouldn’t have any snakes in the opening sequence, just tarantulas. Save the snakes for now.

Spielberg: It would be funny if, somewhere early in the movie he somehow implied that he was not afraid of snakes. Later you realize that that is one of his big fears.

Lucas: It should be slightly amusing that he hates snakes, and then he opens this up, “I can’t go down in there. Why did there have to be snakes? Anything but snakes.”

Now, aren’t you glad they didn’t go with the tigers?