“It is easier to tone down a wild idea than to think up a new one.” — Alex Osborn

I don’t know how you guys do it. Those of you who write alone, I mean.

I am blessed in that I work with a co-author, my sister Kelly. Our collaboration began more than 20 years ago and has lasted through 20-some books (counting the ones that didn’t get published). And while we have had our disagreements over the years, we have always understood the power behind the notion that two brains are better than one.

I want to talk today about brainstorming.

This came about because I was cleaning out my computer folders the other day. I have one folder I labeled BRAIN LINT. This is just a depository for all the stuff I can’t find a good place for but am too gutless to throw out. In this folder are still-born story ideas, pictures cadged from iStock that were meant to inspire, old newspaper articles about bizarre crimes and weirdos, and one completed manuscript that is so bad I keep it just to remind myself of how far I have come and how far I could fall.

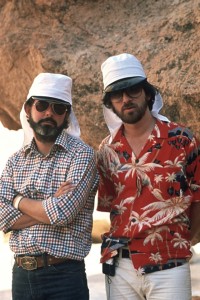

When I was cleaning out the lint, I found one gem. It is a transcript of a story conference in 1978 between Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Lawrence Kasdan. They were brainstorming about a possible movie. It didn’t have a title then, but it would eventually be made under the title Raiders of the Lost Ark. You might have heard of it.

Here’s just one exchange:

Lucas: We want to make a very believable character. We want him to be extremely good at what he does, as is the Clint Eastwood character or the James Bond character. James Bond and the man with no name were very good at what they did. They were very fast with a gun, they were very slick, they were very professional. They were Supermen.

Lucas: We want to make a very believable character. We want him to be extremely good at what he does, as is the Clint Eastwood character or the James Bond character. James Bond and the man with no name were very good at what they did. They were very fast with a gun, they were very slick, they were very professional. They were Supermen.

Kasdan: How do you see this guy?

Lucas: Someone like Harrison Ford, Paul LeMatt. A young Steve McQueen. It would be ideal if we could find some stunt man who could act.

Spielberg: Burt Reynolds. Baryshnikov.

Kasdan: Do you have a name for this person?

Lucas: I do for our leader.

Spielberg: I hate this, but go ahead.

Lucas: Indiana Smith. It has to be unique. It’s a character. Very Americana square. He was born in Indiana.

Kasdan: What does she call him, Indy?

I still can’t get the image of Baryshnikov in a fedora out of a mind. But that was how Indiana Jones was born, out of a brainstorming session between three creative guys. What a strange word – brainstorming. Ever wonder where it came from?

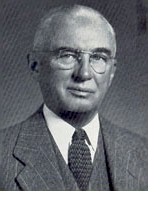

Well, in 1919, Alex Osborn, an ex-newspaper man from Buffalo, joined with Bruce Fairchild Barton and Roy Sarles Durstine to form the hugely successful BDO advertising agency. Osborn went on to write many books on creativity but he’s the one who coined the term “brainstorming.”

Well, in 1919, Alex Osborn, an ex-newspaper man from Buffalo, joined with Bruce Fairchild Barton and Roy Sarles Durstine to form the hugely successful BDO advertising agency. Osborn went on to write many books on creativity but he’s the one who coined the term “brainstorming.”

Nowadays, “brainstorming” is a catch-all for any type of creative group grope. But I thought it might be interesting to go back and see what Osborn had to say about it back in 1953 and find out if it could help writers today. Well, guess what? It’s still good advice, whether you are collaborating, working in a critique group — or even flying solo.

Here’s my main take-aways from Osborn’s ideas on brainstorming.

1. Think up as many ideas as possible regardless of how ridiculous they may seem. It’s unlikely you’ll get the perfect solution right off the bat, so he recommends getting every idea out of your head and then go back to examine them afterwards. An idea that may sound crazy may actually turn out to work with a little modification.

Doesn’t this make sense when you’re plotting? I know when Kelly and I talk, we throw everything on the wall. You need to take the same approach with yourself. Write down every idea and let them bake for a while. Sometimes, the most outrageous thing leads to something useful.

2. Don’t be judgmental. All ideas are considered legitimate and often the most far-fetched are the most fertile. Ideas can be evaluated after the brainstorming session but judgments during the process should be withheld.

Are you sometimes too hard on yourself? Do you think, “Oh, that’s so stupid, no editor will ever buy it.” Or maybe you are a self-doubter, telling yourself, “I don’t have the chops to try this technique.” Or: “This is a great idea but it’s so complex so I won’t even try.”

3. Go for quantity not quality. Don’t get hung up (like I often do) on coming up with the most clever solution to your writing problem. Let your brain waves flow so the bad stuff bobs up to the surface along with the good. Osborn said: “Creativity is so delicate a flower that praise tends to make it bloom while discouragement often nips it in the bud. Forget quality; aim to get a quantity of answers. When you’re through, your sheet of paper may be so full of ridiculous nonsense that you’ll be disgusted. Never mind. You’re loosening up your unfettered imagination—making your mind deliver.”

Osborn’s books were geared more toward corporate types trying to get their teams to think more creatively on things like how to get traffic flowing better in big cities. But take a look at his suggestions for improving creativity and see if there’s not something here for us mere writers:

1. Break up the problem into smaller pieces. For writers, this can mean tackling each plot or character problem as manageable bites, not getting overwhelmed by the idea that you’ve got 400 pages to fill. Get that first draft written then go back and fix your plot holes or layer your characters better.

2. Search for alternatives. If you’ve painted yourself into a plot corner, look for a different way out than the old ways.

3. What can be borrowed or adapted? Read other writers and learn from them.

4. Modify with new twists. There aren’t many new plots in crime fiction but there is always a way to put your own fresh imprint on them.

5. Is there something that can be magnified or minified? Maybe the stakes in your thriller aren’t high enough. Maybe you need to play down a secondary character who is overshadowing your hero. Are you larding in too much research?

6. What can be substituted? Maybe if you changed your location the story would suddenly come alive. Would your mystery work better in a small town where you could exploit the English village dynamic? Is your setting banal and underwritten? Are you hitting all the wrong clichés if your book is set in Paris or some other iconic place?

7. What can be re-arranged? Maybe you’re writing in the wrong point of view? Try switching from first to third. Or maybe the guy you think is your hero is really the bad guy?

8. Consider the vice versa. I love this one. Do just the opposite of what you are now doing. Is your protag male? Switch gender! Are you relying on tired character tropes (lonely alchoholic PI, sweet antique store owner who solves crime). Make your brain do a 180 and examine what is on the flip side. I did this with my latest book. The woman I thought was my protag turned out to be one of two in a dual-protag parallel theme story.

Okay, enough lessons. Let’s end by going back and eavesdropping some more on the Indiana Jones brainstorm session. CLICK HERE to read the whole thing.

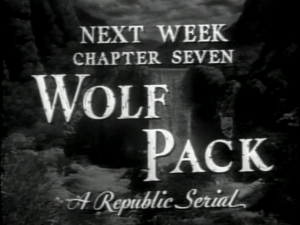

Lucas and Spielberg started with the idea that they wanted to make a movie that was like old Republic serials of the Thirties (Zorro, Dick Tracy, Red Ryder). Something had to always kept happening, every ten minutes or so another cliff-hanger situation. From there, the guys dreamed up Indiana Smith and other elements. In the beginning, even the ark was just a MacGuffin.

Lucas and Spielberg started with the idea that they wanted to make a movie that was like old Republic serials of the Thirties (Zorro, Dick Tracy, Red Ryder). Something had to always kept happening, every ten minutes or so another cliff-hanger situation. From there, the guys dreamed up Indiana Smith and other elements. In the beginning, even the ark was just a MacGuffin.

Lucas: The thing is, if there is an object of antiquity, that a museum knows about that may be missing, or they know it’s somewhere. He can go like an archeologist, but it’s like rather than doing research, he goes in to get the gold.

Spielberg: His main adversaries will be the Germans?

Lucas: Yeah, I think they should be. I’ve been trying to move him around the world a little bit to see if we can’t get a little Oriental influence into it just for the fun of it. I may have fit it in. The fun thing is, he’s a soldier of fortune, so we can move him into any sort of exotic thirties environment we want to.

Spielberg: Keep him out of the States. We don’t want to do one shot in this country.

Lucas: The film starts in the jungle. South America, someplace. We get one of these great scenes with the pack animals going up the mist-covered hills. Very exotic mist-filled jungles and mountains.

Spielberg: Where he goes into the cave?

Lucas: This is where he goes into the cave. We had it where there’s a couple native bearers, whatever, and sort of a couple of Mexican, well not Mexican…

Spielberg: They’re like Mayan.

Lucas: They’re the third world local sleazes…[LATER] He goes into this very sleazy Casablanca type club and makes contact with this agent. The agent is a girl. She’s sort of a Marlene Dietrich tavern singer spy. A German lady singer. She’s really a double agent.

Lucas: They’re the third world local sleazes…[LATER] He goes into this very sleazy Casablanca type club and makes contact with this agent. The agent is a girl. She’s sort of a Marlene Dietrich tavern singer spy. A German lady singer. She’s really a double agent.

Spielberg: I like the idea that she’s a heavy drinker and our hero doesn’t drink at all. She gets drunk a lot. She’s beautiful and she gets really sexy when she’s drunk, and silly. And he doesn’t touch the stuff.

Lucas: I don’t want to soften her. I like the fact that it’s greed. I like all the hard stuff, but you’re going to love her.

Spielberg: There should be a real slimy German character. He’s the only gestapo involved there. Every time you see him, you know it’s going to be the worst pain, death by torture. This guy looks like a ferret. He’s got that slick black hair. His name is Himmler or something like that. He’s a stocky short guy, a master torturer.

Spielberg: There should be a real slimy German character. He’s the only gestapo involved there. Every time you see him, you know it’s going to be the worst pain, death by torture. This guy looks like a ferret. He’s got that slick black hair. His name is Himmler or something like that. He’s a stocky short guy, a master torturer.

Lucas: What can he chase them with? What if he jumps on a camel?

Spielberg: I love it. It’s a great idea. There’s never been a camel chase before.

Lucas: Is this camel going to chase a car?

Spielberg: You know how fast a camel can run? Not only that, he can jump over vegetable carts and things. We still have the big fight in the moving truck to do. And now we have a camel chase.

Lucas: We’ve added another million dollars.

Spielberg: Not really. How much trouble can a camel be?

And then they talk about the big scene toward the end where Indy and Marion are tossed into that deep tomb and the bad guys cover it up with a rock. They’re trying to figure out what is in the tomb that’s dangerous and how Indy gets out. They decide there is a huge artesian well that opens up and he and Marion are in danger of drowning. Then somebody suggests there are also wild animals in the tomb, like tigers.

Spielberg: It would have to be a neighborhood tiger.

Lucas: There aren’t any tigers out there.

Spielberg: I’m not in love with the idea.

Lucas: You could have bats and stuff, make it slightly spooky.

Spielberg: What about snakes? All these snakes come out.

Lucas: People hate snakes. Asps? They’re too small.

Spielberg: It’s like hundreds of thousands of snakes.

Lucas: When he first jumps down in the hole, it’s a giant snake pit. Then when he says they’re afraid of light, they throw down torches. You have a whole bunch of torches that keep the snakes back. So he only has one more torch, and the snakes start coming in. He sits there with one torch, knowing that when the torch goes out… It’s the idea of being in a room, in a black room with a lot of snakes. That will really be scary.

Spielberg: The snakes are waiting, looking at him. Thousands. And the torches are burning down. He’s trying to keep it going. The torch goes out. The whole screen goes black. The sound of the snakes gets more intense. You hear him backing up. The camera pans and suddenly you see, it’s black, but there’s light coming from several cracks. It’s not completely black. That leads him to an opening. To a rock that isn’t so flush against the other rocks. He knows there’s access. He keeps pushing on it, he gets a little more room.

Lucas: We shouldn’t have any snakes in the opening sequence, just tarantulas. Save the snakes for now.

Spielberg: It would be funny if, somewhere early in the movie he somehow implied that he was not afraid of snakes. Later you realize that that is one of his big fears.

Lucas: It should be slightly amusing that he hates snakes, and then he opens this up, “I can’t go down in there. Why did there have to be snakes? Anything but snakes.”

Now, aren’t you glad they didn’t go with the tigers?