Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. Enjoy! I’ll catch ya on the flip side.

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. Enjoy! I’ll catch ya on the flip side.

Title: Side Effects

Genre: Psychological Thriller

All he could hear was the thunder of rushing blood, only distantly aware of the sharp, bright pain in his palms as his fists tightened and fingernails sunk into flesh. He pushed his hands deeper into his pockets and poured his focus into moving more quickly along the crowded sidewalk, but not so quickly as to attract attention. It was a good thing to focus on, a much better thing than the closeness of the warm bodies surrounding him or the intoxicating coppery scent that still lingered in his mind, and as the scope of his concentration narrowed he felt the wild pounding of his heart begin to slow.

Things had gone even worse than he had imagined. Much, much worse. The entire point of taking this job had been to avoid contact with the target. Just simple surveillance and data collection, no face-to-face interaction. No unspoken promise of violence. It hadn’t turned out that way at all, but even with the plan shot all to hell, he couldn’t honestly say that he hadn’t hoped for this.

And that was bad.

An alleyway not choked by storage crates or piles of trash appeared ahead on his right. He darted into it, stopping behind a dumpster and immediately pulling a crumpled pack of cigarettes from his pocket. It was dry here, the layers of fire escapes overhead blocking out the steady drizzle of warm summer rain. He lit up with surprisingly steady hands, the tip of the cigarette flaring as he inhaled deeply and pressed his back against the wall of the alley. The brick was pleasantly cool and rough through the damp fabric of his shirt, and as his lungs burned he felt the first wave of nicotine-fueled calm wash over him.

After a moment he stepped forward and looked around the corner of the dumpster towards the street. Everything seemed normal. There were no sirens, no sprinting cops, no gawking onlookers wandering in the direction from which he’d come. It was unlikely that anything could tie him back to what would be found in that apartment, and that possibility wasn’t what worried him about the situation anyway, but it was good knowing that there was one less problem to deal with right now.

Let’s look at all the things Brave Writer did well.

Let’s look at all the things Brave Writer did well.

- Compelling exposition

- Action; the character is active, not passive

- Raised story questions

- Piqued interest

- Great voice

- Setting established. We may not know the exact city/town, but s/he’s planted a mental picture in the reader’s mind and we can visualize the setting.

- Stayed in the character’s POV

- The title even intrigues me. Side effects of what? Did an injury or drug turn this character into a killer?

The writing could use a little tightening, but nothing too dramatic.

All he could hear was the thunder of rushing blood (anytime we use telling words like hear, we distance the point-of-view. Remember, if you and I wouldn’t think it, our characters can’t either. Quick example of how to reword: Blood rushed like thunder in his ears,) only distantly aware of the sharp, bright pain (Excellent description: sharp, bright pain) in his palms as his fists tightened and fingernails sunk into flesh. from his fingernails biting into flesh.

Technically, only distantly aware would be classified as telling, but I like the juxtaposition between only distantly aware and sharp, bright pain. Some might argue both things can’t be true. Hmm, I’m torn. What do you think, TKZers? Reword or leave it?

He pushed (use a stronger verb like shoved or jammed) his hands deeper into his pockets and poured his focus into quickening his pace moving more quickly along the crowded sidewalk, but not too fast or he might so quickly as to attract unwanted attention. It was a good thing to focus on, a much better thing Better to focus on his stride than the closeness of the warm bodies strangers (the warm bodies sounds awkward to me) surrounding him or the intoxicating coppery scent (Love intoxicating here! Let’s end well, too, by replacing scent with a stronger word. Tang? Aroma? Stench?) that still lingered in his mind,. and

As the scope of his concentration narrowed, he felt the wild pounding of his heart begin to slow. “Felt” is another telling word. Try something like: As he focused on his footsteps, the wild pounding of his heart slowed to a light pitter-patter, pitter-patter.

Things had gone even worse than he’d had imagined. Much, much worse. The entire point of taking this job had been was to avoid contact with the target. Just Simple surveillance and data collection,. No face-to-face interaction. No unspoken promise of violence. It hadn’t turned out that way at all, but even with the plan shot all to hell, part of him he couldn’t honestly say that he hadn’t hoped for this.

And that was bad. The inner tussle between good and evil intrigues me. 🙂

He ducked into aAn alleyway—swept clean, no not choked by storage crates or piles of trash—appeared ahead on his right. He darted into it, stoppinged behind a dumpster, and immediately pullinged a crumpled pack of cigarettes from his (coat?) pocket.

Something to consider: Rather than use the generic word cigarettes, a brand name enhances characterization. Example: Lucky Strikes or unfiltered Camels implies he’s no kid, with rough hands from a lifetime of hard work, a bottle of Old Spice in his medicine cabinet, and a fifth of Jack Daniels behind the bar. A Parliament smoker is nothing like that guy. Mr. Parliament Extra Light would drink wine spritzers and babytalk his toy poodle named Muffin. See what I’m sayin’? Don’t skip over tiny details; it’s how we breathe life into characters. And it falls under fair use as long as we don’t harm the brand. For more on the legalities, read this article.

It was dry here, the layers of fire escapes overhead blocking out the steady drizzle of warm summer rain (If it’s raining, we should know this sooner, perhaps when he’s focused on his footsteps). He lit up with surprisingly steady hands, the tip of the cigarette flaring as he inhaled deeply and pressed his back against the wall of the alley. Love surprisingly steady hands! Those three words imply this is his first murder, and he’s almost giddy about it. Great job!

The cigarette flaring is a bit too cinematic, though. The last thing smokers notice is the end of their butt unless it goes out. If you want to narrow in on this moment, mention the inhale, exhale, maybe he blows smoke rings or a plume, and him leaning against the brick wall. That’s it. Don’t overthink it. Less is more.

The brick was pleasantly cool and rough through the damp fabric of his shirt, and as his lungs burned he felt the first wave of nicotine-fueled calm wash over him.

Dear Writer, please interview a smoker for research. A smoker’s lungs don’t burn. If they did, they’d panic, because burning lungs indicates a serious medical issue. Also, a smoker doesn’t experience a wave of nicotine-fueled calm. It’s too Hollywood. The simple act of him smoking indicates satisfaction. Delete the rest. It only hurts all the terrific work you’ve done thus far.

After a few moments, he chanced a peek at stepped forward and looked around the corner of the dumpster towards the street. Everything seemed normal. There were Nno sirens, no sprinting cops, no gawking onlookers wandering in the direction from which he’d coame. Nothing It was unlikely that anything could tie him back to what would be found in that apartment (let him be certain so when the cops find something later, it throws him off-kilter. Inner conflict is a good thing. Also, simply stating that apartment is enough. We know he killed somebody. Kudos for not telling us who.), and that possibility wasn’t what worried him about the situation anyway, but it was good knowing that there was one less problem to deal with right now. I would end the sentence after apartment, but if you need to add the rest, reword to remove “knowing,” which is also a telling word.

One last note: Use one space after a period, not two.

All in all, I really enjoyed this first page. It sounds like my kind of read. Great job, Brave Writer!

I would turn the page. How ’bout you, TKZers? Please add your helpful suggestions/comments.

The above series of “buts” Provost used in a book proposal for a true crime book entitled Rich Blood. The proposal started a bidding war between publishers.

The above series of “buts” Provost used in a book proposal for a true crime book entitled Rich Blood. The proposal started a bidding war between publishers.

An extreme example: A long time ago, in one of my first critique groups, one author’s character was an activist, giving speeches all over the country. The author had done a good job of writing the speech and the readers ‘heard’ it all on the page (or several pages, as I recall). But then, when the character made the next stop, the author repeated the entire speech verbatim. You can imagine that by the third or fourth delivery of the speech, the reader was tuning out. Now, the author was also adding some new material to the speech, but would the reader stick with it to get to the end of the already way-too-familiar territory to see what was added? Probably not. The group suggested that the only thing the author needed to show was the new stuff.

An extreme example: A long time ago, in one of my first critique groups, one author’s character was an activist, giving speeches all over the country. The author had done a good job of writing the speech and the readers ‘heard’ it all on the page (or several pages, as I recall). But then, when the character made the next stop, the author repeated the entire speech verbatim. You can imagine that by the third or fourth delivery of the speech, the reader was tuning out. Now, the author was also adding some new material to the speech, but would the reader stick with it to get to the end of the already way-too-familiar territory to see what was added? Probably not. The group suggested that the only thing the author needed to show was the new stuff.

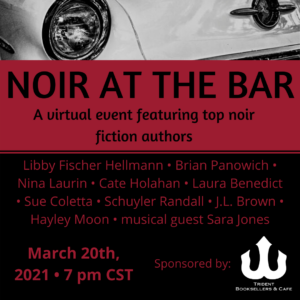

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar.

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar.

If you haven’t watched Justified, check it out. It’s a goldmine for writers. The FX series is based on Elmore Leonard’s short story, Fire in the Hole, and three books, including

If you haven’t watched Justified, check it out. It’s a goldmine for writers. The FX series is based on Elmore Leonard’s short story, Fire in the Hole, and three books, including