The Nearest Exit May Be Behind You

Terry Odell

Keeping readers turning pages is a big thing for authors. Who doesn’t love a message saying “I stayed up all night reading your book”? I’m closing in on ‘the end’ of my first draft of my new book, Cruising Undercover. One of the things I look at on my read through is how I end my scenes. Will a reader be invested enough to turn the page? This is a topic that’s been covered here before, but even though I’m writing novel number thirty-something, it’s a piece of the craft I have to revisit every time. I thought a refresher or reminder might be worthwhile.

Keeping readers turning pages is a big thing for authors. Who doesn’t love a message saying “I stayed up all night reading your book”? I’m closing in on ‘the end’ of my first draft of my new book, Cruising Undercover. One of the things I look at on my read through is how I end my scenes. Will a reader be invested enough to turn the page? This is a topic that’s been covered here before, but even though I’m writing novel number thirty-something, it’s a piece of the craft I have to revisit every time. I thought a refresher or reminder might be worthwhile.

I’m a “self taught” author. That’s not to say I never took classes or workshops, but I was a Psychology major/Biology minor in college. I took the requisite English classes—the ones you couldn’t graduate without. I got decent grades, but I learned more about how to string words together in high school than in those few college classes. I never took a “How to Write” class. The writing courses I took were at conferences or online.

Writing began as a whim. Could I do it? When that moved from writing fan fiction to attempting an actual, original novel, I simply sat down and wrote. My first manuscript was my writing class. That manuscript was one long (140K words) puppy. And there were no chapter breaks. That’s not to say I was trying to avoid using chapter breaks. Rather, it was because I didn’t really know where to put them.

Readers look for reasons to put the book down. They have chores, or work. Kids. Schedules. Bedtimes. Chapter breaks are logical stopping points. Long before I started writing, I learned that if I was going to get any sleep, I had to stop reading mid-page.

A former critique partner referred to these endings as landings. Others have called them hooks.

What makes a reader say Okay, I’ll read a little longer?

Cliffhangers are a tried and true way to get readers to keep going. Leave the character with a dilemma. Jump cuts have been discussed here as well. Since most of my books have alternating POV characters, I often leave one character hanging while I shift to the other’s POV. Since these POV shifts mean each scene has to be a mini-chapter, they need their page-turning landings.

They don’t always have to be character in peril cliffhangers.

You can leave readers with a question they want answered. It could be a phone ringing or a knock at the door. (I use these too often in my first drafts and have to go back and mix things up. You don’t want your chapters to be monotonous or predictable.)

Short chapters, or short scenes are another way, which seems to be a current trend. I recall a workshop given by the late Barbara Parker who told of going to the pool in her apartment complex and asking a woman reading there if she liked the book. The answer, after a moment or two of reflecting, was, “Well, the chapters are short.”

**Personal note: I’m not fond of the super-short chapter. To me, it screams gimmick. Not only that, in a print book, it’s an extreme waste of paper. It’s as if the author or publisher is trying to meet a page count quota and all those short chapters make the book seem longer than the story actually is.

Back to my learning the craft of landings. When I went back and added breaks to my endless tome, I discovered that I’d ended every chapter or scene either with someone driving away or going to sleep. They were, to my still learning the craft mind, logical stopping places. But not exactly page-turners.

More often than not, the best exit was behind where I’d put my break. I’d gone too far, feeling the need to wrap things up. Sometimes a sentence or two was all I needed to cut—usually those extras leaned into telling rather than showing. Sometimes several paragraphs. Once I accepted that those words might still be good, they just weren’t good where they were sitting, it was easier to cut them. I hardly ever needed them, but I felt better knowing that hadn’t been destroyed.

An example of a scene ending from a very early version of what ended up becoming Finding Sarah:

Sarah didn’t care; she cried great gulping sobs until exhaustion overcame her and she slept.

A better version of the ‘end with bedtime’ scenario adds a question:

As she drifted off, she heard a man’s voice from the main house. Had Jeffrey come home?

Here are a couple of examples of “non-cliffhanger, non-action-filled” chapter endings:

From Forgotten in Death, by JD Robb:

Kneeling, she pulled off the work gloves, then resealed her hands. And took a closer look at her second and third victims of the morning.

From A Thousand Bones, by P.J. Parrish

He took another drag on his Camel. “Maybe I will have something else for you as well.”

“What?” Joe asked.

He smiled. “A little surprise.”

What about you TKZ peeps? Do you struggle with ending scenes and chapters? Do you tend to overwrite? What tips can you offer for keeping readers turning pages?

Available Now. In the Crosshairs, Book 4 in my Triple-D Romantic Suspense series.

Available Now. In the Crosshairs, Book 4 in my Triple-D Romantic Suspense series.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

The Prologue of

The Prologue of  Please excuse my using an excerpt from one of my books. I searched my Kindle for other examples but couldn’t find any that jumped out at me.

Please excuse my using an excerpt from one of my books. I searched my Kindle for other examples but couldn’t find any that jumped out at me.

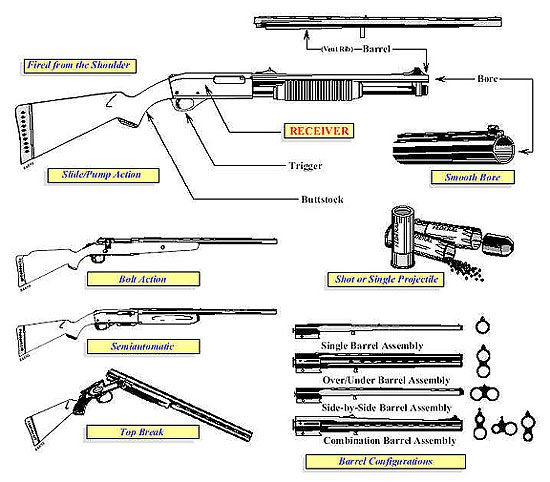

A great example of this is in a current book I read a few weeks ago, where the main character “racked” a shotgun shell into the chamber of her rifle. A quick message to an expert, such as Kill Zone contributor and weapons expert John Gilstrap, and the writer would have learned that racking a shotgun shell into the chamber is an action used for shotguns, not rifles.

A great example of this is in a current book I read a few weeks ago, where the main character “racked” a shotgun shell into the chamber of her rifle. A quick message to an expert, such as Kill Zone contributor and weapons expert John Gilstrap, and the writer would have learned that racking a shotgun shell into the chamber is an action used for shotguns, not rifles.

A novel’s opening chapter makes a promise, a secret vow that says, “This is what you can expect from me.”

A novel’s opening chapter makes a promise, a secret vow that says, “This is what you can expect from me.”

When I’m not reading or watching true crime or nature/wildlife documentaries, I search for net-streaming series based on novels. Why? Because they’re the next best thing to reading, if the series preserves the craft beneath the storyline. Harlan Coben’s STAY CLOSE on Netflix is the perfect example.

When I’m not reading or watching true crime or nature/wildlife documentaries, I search for net-streaming series based on novels. Why? Because they’re the next best thing to reading, if the series preserves the craft beneath the storyline. Harlan Coben’s STAY CLOSE on Netflix is the perfect example.

Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite.

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite. Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime,

Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime,