By Debbie Burke

@burke_writer

Photo credit: Difference Engine, CC by SA 4.0

From the 1931 through 2018, Clifton’s Cafeteria was a venerable Los Angeles landmark. Starting a new restaurant in the depth of the Great Depression sounded like folly. Even crazier was the policy of Pay What You Wish at a time when many people were jobless, broke, and hungry. Yet founder Clifford Clinton’s Golden Rule guided the business through many successful decades, his vision shaped in part by his childhood in China as the son of missionaries who ministered to the poor.

Reportedly, at one point, Ray Bradbury was a starving writer who enjoyed a helping of Clinton’s generosity.

Clifton’s Cafeteria took up multiple floors of a downtown LA building and was a decorating mash-up of art deco neon, tiki bar, mountain resort, and cascading waterfalls.

Buffet lines were laden with acres of salads, soups, entrees, fruits, vegetables, colorful Jello creations, pies, cakes, and ice cream. Diners could pick and choose from more than 10,000 food items and no one ever left hungry.

Photo credit: kevinEats.com

What, you ask, does this have to do with writing mysteries?

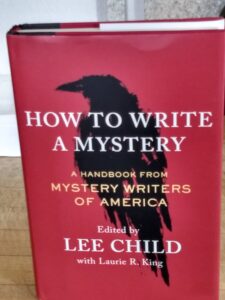

Recently, I received a gift of the book How to Write a Mystery – A Handbook from Mystery Writers of America, edited by Lee Child with Laurie R. King. With nearly 70 contributors, the book feels like the literary equivalent to Clifton’s Cafeteria. It offers a hugely varied smorgasbord of craft tips, along with insights into different genres, trends, and analyses on the state of the mystery.

Some authors write detailed essays that take as much digestion as multi-course banquets. Others deliver bite-size epigraphs that you can pop in your mouth like cocktail meatballs.

Moving along the buffet line of advice, if one chapter doesn’t resonate, you can skip to another by a different author. Each contribution is self-contained, allowing you to read sections in any order without worrying about continuity.

Feel like dessert before your entree? Head to that part of the buffet line.

Craving a particular menu item? Flip to the table of contents to find that topic.

Even famous authors don’t always agree with each other. Jeffrey Deaver writes a chapter entitled “Always Outline,” followed by Lee Child’s chapter, “Never Outline!”

This book offers nourishing food for thought that’s useful to every reader, no matter your genre, writing experience, or where you come down on the plotting vs. pantsing spectrum.

Subjects range from bleak noir as dark as bitter chocolate to cozies as sweet and fluffy as lemon meringue pie.

The following are some passages that struck me. They made me look at a subject in a fresh way while others reinforced well-worn but forgotten wisdom.

Neil Nyren neatly boils down an important distinction:

Mysteries are about a puzzle. Thrillers are about adrenaline.

Carolyn Hart asks:

Aren’t all mysteries about murder, guns and knives and poison, anger, jealousy and despair? Where is the good?

The good is in the never-quit protagonist who wants to live in a just world. Readers read mysteries and writers write mysteries because we live in an unjust world where evil often triumphs. In the traditional mystery, goodness will be admired and justice will prevail.

Meg Gardiner’s simple definition of plot: “Obstruct desire.”

She also discusses the difference between suspense and tension. “Suspense can be sustained over an entire novel. Tension spikes like a Geiger counter at a meltdown.”

And one more gem: “The theater of the mind is more powerful than a bucket of blood.”

My favorite item on Lindsey Davis’s list of advice to aspiring writers: “A synopsis—write it, then ignore it.”

Alex Segura defines noir as:

When we can have some feelings of remorse for a character’s terrible, murderous actions, because deep down, we fear that in the same situation, we’d probably make similar choices.

Hank Phillippi Ryan’s editing suggestions:

Try this random walk method of editing. Pick a page of your manuscript. Any page at all. Remember, even though you’re writing a whole book, each page must be a perfect part of your perfect whole, and that means each individual page must work. Page by page…Is something happening?…[Consider] intent and motivation. Why is this scene here? What work does it do? Does it advance the plot or reveal a secret or develop the character’s conflict?

I always know when I’m finished, because I forget I’m editing, and realize I’m simply reading the story. It’s not my story anymore, it’s its own story.

Jacqueline Winspear talks about historical mystery: “Your job is to render the reader a curious, attentive, excited, and emotionally involved time-traveler.”

Suzanne Chazin says: “When I sit down to write, my fun comes not from looking into a mirror, but from peeking into someone else’s window.”

Medical thriller author and physician Tess Gerritsen makes a penetrating observation from a sales standpoint:

Thrillers about cancer or HIV or Alzheimer’s seem to have a tough time on the genre market. Perhaps because these subjects are just too close and too painful for us to contemplate, and readers shy away from confronting them in fiction.

Gayle Lynds believes research is more to benefit the writer than the reader:

In the end, we novelists use perhaps a tenth of a percent of the research we’ve done for any one book…only a tiny fraction of the details will make it into your book.

C.M. Surrisi sums up writing mysteries for kids: “Remember your protagonist can’t drive and has a curfew, and no one will believe them or let them be involved.”

Also on children’s mysteries, Chris Grabenstein says:

Here is one of the many beauties about writing for this audience: there is a new group of fifth graders every year. Your mystery has a chance to live a very long shelf life if kids, teachers, and librarians fall in love with it.

Avoid the broccoli books. The ones that are ‘good for children.’

For many adults, the books we read when we were eight to twelve are the ones we remember all our lives.

Art Taylor discusses the mystery short story:

In general, it’s a solid rule to try to do more with less—and to trust your reader to fill in the rest. Suggest instead of describe; imply instead of explain.

Charles Salzberg offers a response to the tired old saw of “write what you know.”

I’ve never been arrested; I have no cops in my family; I’ve only been in a police station once; I’ve never handled a pistol; I’ve never robbed a bank, knocked over a 7-Eleven, or mugged an old lady. I’ve only been in one fight and that was when I was eleven. I’ve never murdered anyone, much less my family, and I’ve never chased halfway around the world to bring a killer to justice. I’ve never searched for a missing person and I’ve never forged a rare book. Yet somehow I find myself as a crime writer who’s written about all those things.

How, if I am supposed to write only what I know, is this possible? Easy. It’s because I have an imagination, possess a fair amount of empathy, have easy access to Google, and like asking questions. If I were limited to writing what I know, I’d be in big trouble because the truth is, I don’t know all that much.

Lyndsay Faye observes: “The school of human culture is much cheaper than a graduate degree. Make use of it.”

She also talks about humor in the writer’s voice:

You needn’t be Janet Evanovich to incorporate jokes into your manuscript, and they needn’t even be jokes. Wry observations, sarcasm, creative insult—humor can be as heavy or as light as you choose. But writers who take their voice too seriously, without that crucial hint of self-deprecation or clever viciousness, will rarely wind up with a memorable result.

Steve Hockensmith covered the “Dos and Don’ts for Wannabe Writers.”

DO write.

DON’T spend more than three months ‘researching’ or ‘brainstorming’ or ‘outlining’ or ‘creating character bios.’ All this might—might—count as work on your book, but it’s not writing.

DON’T spend too much time reading about how to write.

DO keep reading this book. I didn’t mean for you to stop reading our writing advice.

Laurie R. King shares her method of rewriting:

Personally I prefer to make all my notes, corrections, and queries on a physical printout. In part, that’s because I’m old school, but it also forces me to consider any changes twice—once when I mark the page, then again when I return to put it into the manuscript. This guarantees that if I added something on page 34, then realized a better way to do it when I hit page 119, I’ve had the delay for reflection, gaining perspective as to which is better for the overall story.

Leslie Budewitz (a familiar guest on TKZ) talks about problem solving:

The same brain that created the problem can create the solution—but not if you keep thinking the same way.

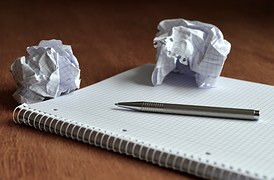

So do something different. Write the next scene from the antagonist’s POV, even if you don’t intend to use it. Write longhand with a pen…instead of at your keyboard.

If you write in first person, try third. If you write in third, let your character rip in a diary only she—and you—will ever see.

Your brain, your beautiful creative brain, will find another way, if you give it a chance.

Frankie Y. Bailey explores diversity in crime fiction from the starting point every writer faces: “We have characters, setting, and a plot. We need to weave aspects of diversity through all these elements of our stories.”

TKZ’s own Elaine Viets offers this no-nonsense message: “When I spoke at a high school, a student asked, ‘What do you do about writer’s block?’ ‘Writer’s block doesn’t exist,’ I said. ‘It’s an indulgence.’”

Talking about protagonists, Allison Brennan shares “two particular qualities that leave a lasting impression on readers: forgiveness and self-sacrifice.”

T. Jefferson Parker sees “two types of villain: the private and the public.”

The private ones seek no acknowledgement for their deeds…they shun the spotlight and avoid detection. The public ones proclaim themselves, trumpet their wickedness, and revel in the calamity.

He also touches on the crime author’s moral dilemma:

My literary amigos and I go back and forth on this. We know we traffic in violence and heartless behavior. We ride and write on the backs of victims. We suspect that our fictional appropriations of the world’s pain do little to assuage it. Worse, we wonder if we might just be feeding the worst in human nature by putting it center stage. Do we inspire heartless violence by portraying it?

Stephen Ross demonstrates the use of subtext (unspoken meaning) in his example of a shopping list:

Milk

Bread

Eggs

Hammer

Shovel

Quicklime

Champagne

I highlighted many more passages but I’ll stop now because this post is running almost as long as the book itself.

I highlighted many more passages but I’ll stop now because this post is running almost as long as the book itself.

How to Write a Mystery is a book that you can read whether you need a substantial dinner or a quick snack.

It might not offer the 10,000 items that Clifton’s Cafeteria did but it comes close.

~~~

TKZers: Did any of the above quotes especially hit you? Do you have a favorite craft handbook you refer to over and over?

Readers and movie viewers typically don’t take comic villains seriously because they’re often lousy criminals. They’re buffoons whose sloppy schemes go awry. Their supposedly clever strategies explode in their faces. Their mistakes get them knocked on their butts.

Readers and movie viewers typically don’t take comic villains seriously because they’re often lousy criminals. They’re buffoons whose sloppy schemes go awry. Their supposedly clever strategies explode in their faces. Their mistakes get them knocked on their butts.

I highlighted many more passages but I’ll stop now because this post is running almost as long as the book itself.

I highlighted many more passages but I’ll stop now because this post is running almost as long as the book itself.