Research to Right the Wrongs … and Mary Poppins

Guest Blog by Lee Lofland

Given I was still supposed to be in Antarctica this week (long, sad story), I’d asked Lee Lofland to fill in, and his post is definitely worth reading, so I’m turning the stage over to him.

Retired cop Lee Lofland got so sick of reading blatant errors in police procedure that he founded the Writers’ Police Academy, which is where I met him. I can’t recommend this conference enough for its hands on experiences and workshops given by experts–one of whom was TKZ’s own John Gilstrap. I’ve attended at least four times and learn something new every time. But I’ve rambled long enough … take it away, Lee.

Writers sometimes bypass the research portion of their craft and rely on rehashing outdated inaccuracies and dog-tired cliches about police. Unfortunately, allowing those blunders to wiggle and squirm their way into dialog, scenes, characters, and settings is occasionally the factor that sends once loyal readers to the words of another author.

Writers sometimes bypass the research portion of their craft and rely on rehashing outdated inaccuracies and dog-tired cliches about police. Unfortunately, allowing those blunders to wiggle and squirm their way into dialog, scenes, characters, and settings is occasionally the factor that sends once loyal readers to the words of another author.

I’m always amazed to learn of the writer who still uses cop-television as a research tool over the many true experts who make themselves available to writers. A great example of a wonderful resource for writers is this blog, Kill Zone. The combined knowledge shared by the contributors to this site is a treasure-trove of information.

With the so many top law enforcement resources available to writers, why, I often wonder, do some still consider as accurate the things they see on television shows such as Police Squad and the woefully ridiculous Reno 911? Even top-rated crime dramas take shortcuts and often make errors in police procedure, cop-slang, etc. It’s TV, and the duty of writers and producers of fictional shows is to entertain, not educate viewers about the NYPD Patrol Guide.

Writing a novel is, of course, a completely different enterprise than writing a television show. Scenes and action play out at a much slower pace; therefore, readers have more time to absorb and analyze the action and how and what characters are doing and WHY they’re doing it.

Shows like Star Trek and Amazon Prime’s Reacher are fiction, but viewers are easily drawn into the action. They’re engaged in what they see on screen because writers provide plausible reasons for us to accept what we’re seeing. (believable make-believe).

The ability to expertly weave fact into fiction is a must, when needed. But writers must have a firm grasp of what’s real and what’s made-up before attempting to use reality as part of fiction.

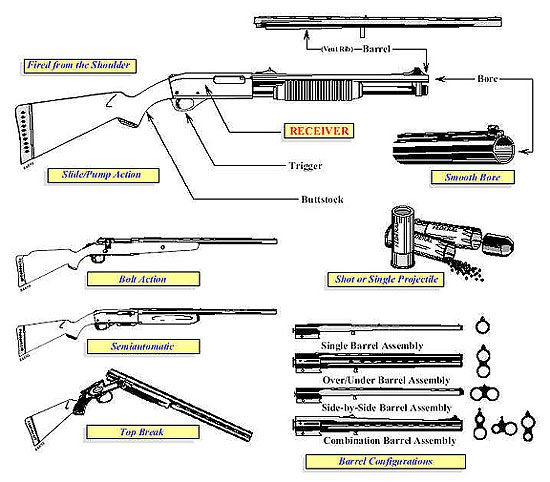

For example, confusing a semi-auto pistol with a revolver, or a shotgun with a rifle. Those are the sorts of things that cause writers to lose credibility with their readers.

A great example of this is in a current book I read a few weeks ago, where the main character “racked” a shotgun shell into the chamber of her rifle. A quick message to an expert, such as Kill Zone contributor and weapons expert John Gilstrap, and the writer would have learned that racking a shotgun shell into the chamber is an action used for shotguns, not rifles.

A great example of this is in a current book I read a few weeks ago, where the main character “racked” a shotgun shell into the chamber of her rifle. A quick message to an expert, such as Kill Zone contributor and weapons expert John Gilstrap, and the writer would have learned that racking a shotgun shell into the chamber is an action used for shotguns, not rifles.

The writing in the book was wonderful, and the story flowed as easily as melting butter oozing from a stack of hot pancakes … until I read that single line. At that point, as good as the book had been, from that point forward I found myself searching each paragraph for more errors.

The writing in the book was wonderful, and the story flowed as easily as melting butter oozing from a stack of hot pancakes … until I read that single line. At that point, as good as the book had been, from that point forward I found myself searching each paragraph for more errors.

So, what are some of the more glaring police-type errors often seen in crime fiction? Well …

- When shot, people fly backward as if they’d been launched from a cannon. NO. When struck by gunfire, people normally fall and bleed. Sometimes they cuss and yell and even get up and run or fight.

- “Racking the slide of a pistol” before entering a dangerous situation is a TV thing. Cops carry their sidearms fully loaded with a round in the chamber. Racking the slide would eject the chambered round, leaving the officer with one less round.

- People are easily knocked unconscious with a slight blow to the head with a gun, book, candlestick, or a quick chop to the back of the neck with the heel of the hand. NO! I’ve seen people hit in the head with a baseball bat and they never went down.

- FBI agents do not ride into town on white horses and take over local murder cases. The FBI does not have the authority to investigate local murders. All law enforcement departments, large and small, are more than capable of solving homicides, and FBI agents have more than enough to do without worrying about who shot Ima D. Crook last Saturday night.

- The rogue detective who’s suspended from duty yet sets out on his own to solve some bizarre and unrealistic case. He’s the alcoholic, pill-popping unshaven guy who never combs his hair, wears a skin-tight t-shirt and leather jacket, and carries an unauthorized weapon tucked into the rear waistband of a pair of skinny jeans. No. If an officer is suspended from duty, they are forbidden to conduct any law-enforcement-related business. Many departments require that suspended officers check-in daily with their superiors.

- CSIs do not question suspects, nor do they engage in foot pursuits, shootouts, and car chases. Typically, they’re unarmed and come to crime scenes after the scene is clear.

- Revolvers do NOT automatically eject spent brass.

- Cops cannot tell the type of firearm used by looking at a bullet wound.

- Cops do NOT fire warning shots.

- Cops do NOT shoot to kill.

- Cops shoot center mass, the middle of the largest target, because it’s the easiest target to hit when even a second could mean the difference between life or death for the officer.

- Cops do NOT shoot to wound. They shoot to stop a threat.

Imagine that a man suddenly turns toward you, an officer. He has a gun in his hand, and it’s aimed at you. His finger is on the trigger, and he says he’s going to kill you. How do you react?

First, the scene is not something you’d expected, and in an instant your body and brain must figure out what’s going on (perception). Next, the brain instructs the body to stand by while it analyzes the development (Okay, he has a gun and I think I’m about to be shot). Then, while the body is still on hold, the brain begins to formulate a plan (I’ve got to do something, and I’d better do it now). Finally, the brain pokes the body and tells it to go for what it was trained to do—draw pistol, point the business end of it at the threat, insert finger into trigger guard, squeeze trigger.

To give you an idea as to how long it takes a trained police officer to accomplish those steps, let’s visit Mary Poppins and Bert the chimney sweep from the movie Mary Poppins. More specifically, that wacky word sung by Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke—supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.

The time it takes me to say the word is somewhere between 1.01 seconds and 1.22 seconds, depending upon how quickly I start after clicking the button on the stopwatch. To put this scenario into perspective, the average police officer’s reaction time (based on a study of 46 trained officers), when they already know the threat is present (no surprises), AND, with their finger already on the trigger, is 0.365 seconds. That’s less than half the time it takes Bert to sing that famous word.

In short, in a deadly force situation like the one mentioned above, police officers must decide what to do and then do it in the time it takes to say “supercali.” Not even the entire word.

Considering that hitting a moving object such as an arm or leg while under duress is extremely difficult, if not impossible for some, shooting to wound is not a safe option when a subject is intent on shooting the officer.

- Cops do NOT use Tasers when the situation calls for deadly force.

- Cops should never use deadly force when the situation calls for less than lethal options, such as Taser, pepper spray, baton, etc.

Finally, unless you’re writing historical fiction, your characters will not smell the odor of cordite. Cordite manufacturing ceased at the conclusion of WWII; therefore, scenes written in the past 75 years or so shouldn’t contain anything resembling, “I knew he’d been shot within the past few minutes because the scent of cordite still lingered in the air.”

Lee Lofland is a veteran police detective and recipient of the Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police Medal of Valor. He’s the author Police Procedure and Investigation, blogger at The Graveyard Shift, and founder and director of the popular Writers’ Police Academy, a hands-on training event for writers, and Writers’ Police Academy Online.

Lee Lofland is a veteran police detective and recipient of the Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police Medal of Valor. He’s the author Police Procedure and Investigation, blogger at The Graveyard Shift, and founder and director of the popular Writers’ Police Academy, a hands-on training event for writers, and Writers’ Police Academy Online.

Insightful. Thank you Lee, and our resident weapons expert John Gilstrap, for keeping us grounded in reality even as we get lost in our fictive worlds.

Welcome to TKZ, Lee. Thanks, Terry, for hosting him.

The Writers Police Academy sounds terrific. Hope to attend someday.

Years ago, in our Montana county, the local sheriff sponsored the Sheriff’s Citizens’ Academy, a ten-week course that covered evidence collection, patrol, SWAT, serving warrants, crimes against children, tours of the jail and 911 center, ridealongs, etc., etc. I took the course several times and wrote a series of magazine articles about it.

Additionally, alumni were asked to role-play for reserve officer training sessions. In one, I was stopped for suspected drunk driving and learned how hard it is to walk heel-to-toe in a straight line even stone-cold sober. Other times, I portrayed the distraught mother of an injured child and a rape victim.

The inside look gave me new respect for what officers have to face every day.

Great information. I usually do the same amount of research: Too much. Depending on the topic/era/story, up to half the known “facts” may turn out to be bogus.

The error I see a lot: (1) Villain gets the drop on Mike Sledge, P.I. (2) Lazy writer wants Sledge to survive, so (3) Villain “stumbles” and drops gun. (4) Sledge disposes of villain.

But when someone starts to fall, they instinctively clutch whatever they have in their hand(s). They don’t drop it, no matter how convenient that may be. When “Pay It Forward” used the stumble trick, I almost tossed my popcorn.

In a big name “author’s” procedural, a prime suspect evades a stakeout by cleverly exiting his house via the back door. Whoa! Will the cleverosity never end?

Thank you, Terry, and welcome, Lee. Thanks for the good, strong dose (several gallons worth, really) of reality on a Wednesday morning, particularly with respect to the “shooting to wound” canard. This is a keeper.

Bypass the research? No. Get lost in it? Yes. LOL! And sometimes you make a blunder with research even when you try to be meticulous–because some projects you’re writing involve so much research on so many levels that it can become easy to miss something.

So I’m thankful for blog posts like this to keep these kinds of details on our radar. As a reader, I myself would be less likely to catch a weapons error, but I know for others that would drive them nuts. It’s worth taking the time to get it right.

Thanks, Lee and Terry. Great post, Lee.

Very useful information. Well organized and presented. The Writer’s Police Academy sounds very interesting, something I will look into.

Lee, thanks for filling in for Terry, I hope you come back again!

I prefer the realism of the Western sheriff shooting the gun out of the bad guy’s hand.

Thanks for stopping by, Lee.

Thanks, Terry, for inviting Lee to guest post today. And thanks, Lee, for the informative article. (And working Mary Poppins into an article about police procedure and firearms! Very creative. Now I’ll have that song in my head for the rest of the day. 🙂

I’d like to attend the Writers’ Police Academy at some point. I notice you have an online version that I’ll look into.

Thanks, Everyone. Thank you, too, Terry for inviting me to fill in during your time away.

I’m glad you’ve found the information useful. It’s always a pleasure to hear writers express a desire to learn, even when it means going an extra mile to do so. It’s been wonderful to see crime fiction make a turn away from the use of many tired cliches and being marred by the use of many tired cop-esque clichés and inaccuracies. It’s a sure sign that writers are paying attention to the needs and wants of their readers.

Terry, thanks for having Lee as a guest this morning. Lee, thanks for sharing your knowledge with us, as well as walking us through the very short amount of time a police officer has to make a decision in a potential deadly situation. I’d also like to attend the Writers Police Academy someday, too.

Knowledgeable friends took my wife and I to a local gun range on two occasions a few years ago and ran us through using different firearms, gun safety, shooting at targets etc, which gave this writer a bit of real-world experience.

Your cliche list was great, too.

Thanks again for being here!

Hey, Lee! Nice to “see” you on TKZ. Fab info as always. Thank you!

I loved my time at the Writers Police Academy. All my instructors were top-notch and super nice. Looking forward to attending again in the near future.

By the way, in case you didn’t recognize her, that’s author Tami Hoag in the top photo (far right). The picture was taken at the rifle/long gun range at the Writers’ Police Academy.

Such an interesting post on firearms and shooting victims and police officers under duress. Excellent info!

My elder brother and I were watching a mystery show and between us, we spotted 16 factual errors in the first half of the show. TV not only fails to get police work right, it can’t even get reality right.

Always insightful. TV is particularly bad. My wife is a big fan of NCIS. Some of the best one shot cops in all of fiction.

I was looking for the video of Geoffrey Boothroyd. He was an English firearms trainer. He wrote a letter to Ian Fleming pointing out Bond’s .25 Barretta was “a ladies gun” and that Bond needed more stopping power.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffrey_Boothroyd#James_Bond

The other thing on TV is the sound of a gun. The earth shaking boon isn’t a pistol. Let’s say I have worked in neighborhoods were knowing firecracker, 9m, and 10 gauge is useful.

Thanks for a great post, Lee. I’ve been to two WPAs and learned so much, plus it was so much fun! I don’t know why Lee didn’t mention it, but he has a fantastic website and blog –it’s the first place I go when I start my research for something I need to know for my story: https://leelofland.com/the-graveyard-shift-blog/

After you read the blog, poke around his website–you’ll learn a lot. And if you’re wondering how it feels to be in a gun battle, find the post that Lee wrote about the time he was in one.

Thanks for the mention of my blog. Later today (6 p.m. EST) I’m posting the first of my reviews of REACHER, the TV series based on Lee Child’s books. The reviews examine the police procedure and forensics used in the show.

A while back, I wrote similar reviews of the shows CASTLE and SOUTHLAND. Southland actors, directors, producers, and writers took an active part in many of those reviews and I was often invited to participate in chat sessions with fans of the show, where I answered questions about the realistic police aspects of the series. One year, Michael Cudlitz, the star of the show, announced the winner of the Writers’ Police Academy’s Golden Donut Short Story Contest. You may have also seen Michael in Band of Brothers and The Walking Dead, among other shows. It was a lot of fun.