Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

The most important thing to remember is to play fair. Clues must be in plain sight. We cannot reveal a clue that wasn’t visible earlier. That’s cheating.

A few years ago, I read a novel about [can’t name the profession without giving away the title]. The protagonist located the dead and solved every mystery with invisible clues. After I whipped my Kindle across the room, I took a deep breath and skimmed the story searching for the clues. Never found one. Not one! The author’s name now sits at the pinnacle of my Do Not Read list.

A key feature of good misdirection means you brought attention to the clue, and the reader still missed it.

A magician uses three types of misdirection:

- Time: The magician has the silk scarf balled in one fist before he begins the trick.

- Place: The magician draws your attention to his right hand while the real trick is happening in his left.

- Intent: The magician leads you to the decision he wants, but afterward you’ll swear you had a choice.

Notice any similarities to writing?

Misdirection can be either external or internal. External would be when the author misdirects the reader. Internal is when a character misdirects another character.

Misdirection is different than misinformation. We should never outright lie to the reader. Rather, we let them lie to themselves by disguising the clue(s) as inconsequential.

How do we do that?

When you come to a part of the story where nothing major occurs, slip in a clue. Or include the detail/clue while fleshing out a character’s life.

Examples:

One character chats with another as they drive to a designated location. Is the locale a clue in and of itself?

What about the title of the book? The reader has seen the title numerous times, yet she never gave it much thought until the protagonist reveals its meaning to the plot.

Clandestine lovers meet in a hideaway. While there, one of the characters notices a symbol or sign. Later in the story, she finds another clue that relates to the sign or symbol. Only now, she has enough experience to interpret its true meaning.

A kidnapper chalks an X on a park bench to signal the drop-off spot. What if a stray dog approaches the kidnapper? If he reads the dog’s tag to find his human, the clue takes center stage, yet it’s disguised as inconsequential.

In all four examples the arrival of the clue seems insignificant at first. The reader will notice the clue because we’ve drawn attention to it, but we’ve framed it in a way that allows the character to dismiss it. Thus, the reader will, too.

False Trails

The character knows the clue is important when she finds it, but she misinterprets its meaning, leading her down a dead end.

What if we need to supply information on a certain topic, but we don’t want the reader to understand why yet? If we take the clue out of context and present it as something else—something innocuous or insignificant—we’ve misdirected the reader to reach the wrong conclusion.

An important factor of misdirection is that the disguise must make sense within the confines of the scene. It should also further the plot in some way.

“Misdirection can be used either strategically or tactically. Strategically to change the whole direction of a story, to send it off into a new and different world, and have the reader realize that it’s been headed that way all along. Tactically to conceal, obscure, obfuscate, and camouflage one important fact, to save it for later revelation.”

— The Writer magazine

Character Misdirection

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite.

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite.

Two types of character misdirection.

- False Ally

- False Enemy

These two characters are not what they seem on the surface. They provide opportunities for dichotomy, juxtaposition, insights into the protagonist, theme, plot, and plot twists. They’re useful characters and so much fun to write.

A false ally is a character who acts like they’re on the protagonist’s side when they really have ulterior motives. The protagonist trusts the false ally. The reader will, too. Until the moment when the character unmasks, revealing their false façade and true intention.

A false enemy is a character the protagonist does not trust. Past experiences with this character warn the protagonist to be wary. But this time, the false enemy wants to help the protagonist.

When Hannibal Lecter tries to help Clarice, she’s leery about trusting a serial killing cannibal. The reader is too.

What type of character is Hannibal Lecter, a false ally or false enemy?

An argument could be made for both. On one hand, he acts like a false enemy, but he does have his own agenda. Thomas Harris blurred the lines between the two. What emerged is a multifaceted character that we’ve analyzed for years.

When crafting a false ally or false enemy, it’s fine to fit the character into one of these roles. Or, like Harris, add shades of gray.

Mastering the art of misdirection is an important skill. It’s especially important for mysteries and thrillers. I hope this post churns up new ideas for you.

Do you have a false ally or false enemy in your WIP? What are some ways you’ve employed misdirection?

This is my final post of 2021. Wishing you all a joyous holiday season. See ya in the New Year!

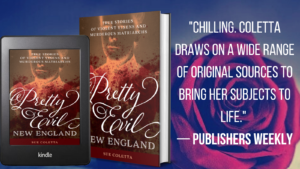

Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime, Pretty Evil New England is on sale for $1.99. Limited time. On Wednesday, Dec. 15, the price returns to full retail: $13.99.

Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime, Pretty Evil New England is on sale for $1.99. Limited time. On Wednesday, Dec. 15, the price returns to full retail: $13.99.

My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers. Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. Enjoy! I’ll catch ya on the flip side.

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. Enjoy! I’ll catch ya on the flip side.

But it’s not as simple as that, is it? Persistence can be grueling at times.

But it’s not as simple as that, is it? Persistence can be grueling at times. To master the art of writing we need to read. Whenever the words won’t flow, I grab my Kindle. Reading someone else’s story kickstarts my creativity, and like magic, I know exactly what I need to do in my WIP.

To master the art of writing we need to read. Whenever the words won’t flow, I grab my Kindle. Reading someone else’s story kickstarts my creativity, and like magic, I know exactly what I need to do in my WIP.

The above series of “buts” Provost used in a book proposal for a true crime book entitled Rich Blood. The proposal started a bidding war between publishers.

The above series of “buts” Provost used in a book proposal for a true crime book entitled Rich Blood. The proposal started a bidding war between publishers.