Who is your favorite dead writer?

If you could ask him or her one question, what would it be?

I’m thrilled to host Adam Croft as a guest on the Kill Zone. Adam is one of the leading indie authors in today’s crime thriller market. He’s sold over two million books in the past few years and several times he’s held the #1 Best Seller spot on all of Amazon—ahead of names like JK Rowling, James Patterson, and the King (Stephen King, that is.)

I’m also proud to say (brag) that Adam and I have been friends since 2014. That was before Adam Croft was famous and when I still had hair. We’ve cross-blogged, shared personal emails, had some laughs, and he’s been a highly-influential mentor on my writing and publishing journey through his leadership in The Indie Author Mindset.

But, enough of what’s in it for me. Here’s what Adam Croft has to say about why readers love crime thrillers.

Human beings are fascinated by death and reading crime thrillers. As morbid and unsavory as that sounds, it’s a good job they are as otherwise I wouldn’t be here writing this article and you wouldn’t be reading it.

If we did not have a fascination with death, one of the world’s most popular and enduring fiction genres would not exist and I’d be out of a job. So I’m pretty pleased that we do. But, what has caused us to be hardwired to think in this way? What makes death and murder in particular so fascinating to us?

Fascination goes hand in hand with intrigue, and it is to intrigue that we must turn first. Naturally, human beings are intrigued by why someone would want to kill another human being. To most of us, committing a murder is unthinkable.

Of course, we’ve all known people that we’d love to kill, but actually contemplating doing it is something entirely different. This intrigue surrounding those who do, then, is entirely natural. It’s one of society’s final taboos, and we are naturally intrigued by the ways in which people murder each other.

There’s also a sense of needing to understand, which is what compels our sense of intrigue. Naturally and evolutionarily, we feel the need to understand the situation of murder in order to protect our species and prevent or predict future occurrences. It would be fair to say that this is an in-built, animalistic sense, which puts our fascination at a level much deeper than sheer intrigue.

There’s also a sense of needing to understand, which is what compels our sense of intrigue. Naturally and evolutionarily, we feel the need to understand the situation of murder in order to protect our species and prevent or predict future occurrences. It would be fair to say that this is an in-built, animalistic sense, which puts our fascination at a level much deeper than sheer intrigue.

However, this would be a little too simplistic. Why, then, do real-life murders not fascinate us as much as they did in Victorian times, when newspaper circulation figures would regularly treble off the back of a good murder?

Nowadays, we’re far more satisfied to get our dose of death through fiction like crime thrillers. We know fiction isn’t real, so the purely evolutionary theories go out of the window at this point. In my opinion, it’s the complexity and make-up of the murder mystery or crime thriller novel which provides the fascination here.

The truth is that most real-life murder is actually incredibly pedestrian. There’s a fight and someone dies. A jealous husband murders his ex-wife. There’s a gangland killing. No particular element of mystery comes into play with any of these situations, which leads me to posit that our fascination with murder is no longer rooted in our desire to protect our species but instead with the logic of the puzzle and the mystery surrounding a well-constructed crime thriller novel.

The longevity of the mystery/crime novel is rooted in its complexity and infinitely changing forms. The number of ways in which a crime is committed, and the reasons for someone wanting to commit it, is what keeps crime thriller novelists like me in a job.

A clever and sophisticated plot is what readers crave, and it’s the reason why Agatha Christie is the best-selling author of all time. Her proficiency for developing the twists and turns and ingenious plots for which she was most famed is the reason why people keep going back to her time after time.

The most us modern-day mystery and crime thriller writers can hope for, following far behind in her wake, is that we might be able to side-step the reader somewhere along the way and leave them guessing to the last.

It would be far too simplistic, though, to say that we’re now purely interested in the type of brain-teasing mystery akin to a crossword puzzle. There’s certainly still a psychological element involved, which is why psychological thrillers are huge business.

As a species, we pay attention to these sorts of plots because we have an animalistic need to know we are safe. We need to understand the mind of the killer.

This understanding is the reason why psychology courses and degrees are so popular in the western world, and particularly in Britain, where the murder mystery is particularly venerated.

Human beings have an innate desire to understand ourselves and other human beings.

If you’ll forgive me adopting a purely political point of view for a moment, this is a very heart-warming realization from a progressive perspective, as our need to understand each other as human beings is something which we’ve been sadly lacking for most of our existence as a species.

We can be sure that crime fiction will last, and there are a number of reasons for this. Crime’s bedfellow in terms of sheer popularity is undoubtedly the romance genre; a type of book which offers resolution and has well-rooted and respected forms and conventions.

Naturally, it has had to adapt and recent years have seen the rise of rom-coms and even the sub-genre of erotica (although many, including myself, would either put erotica into a sub-genre of thrillers or a genre all of its own).

Mystery, too, has had to adapt. Writers such as P.D. James have prided themselves in breaching the (admittedly small) gap between crime and literary fiction, combining a well-written book with a tight and intricate plot.

It would be worth me noting here that the concept of ‘literary fiction’ does not exist to me. The only great literature is a book that you enjoy. Crime thriller novels, generally speaking, have the added benefit of being stripped of pretension and putting the reader first, not setting the writer on an undeserved pedestal. The enduring popularity of the genre is a testament to its superiority.

It would be fair to say, then, that the crime thriller and mystery genre can be expected to live on. As our fascination with death and our need for logical complexity continue to be fused together beautifully by fiction, we can be assured of even more great books to come. It’s because people love to read crime thrillers.

With over two million crime thriller books sold in over 120 countries, Adam Croft is one of the most successful independently published authors in the world. His crime thrillers Her Last Tomorrow and Tell Me I’m Wrong topped the Amazon and USA Today charts. His new release, What Lies Beneath, starts a new series for Adam that might exceed everything he’s already accomplished.

With over two million crime thriller books sold in over 120 countries, Adam Croft is one of the most successful independently published authors in the world. His crime thrillers Her Last Tomorrow and Tell Me I’m Wrong topped the Amazon and USA Today charts. His new release, What Lies Beneath, starts a new series for Adam that might exceed everything he’s already accomplished.

And, Adam Croft was an accomplished stage actor before turning indie-writer ten years ago. His first crime thrillers were the Knight & Culverhouse series. He also developed his Kempston Hardwick series before writing super-successful stand-alones. Now, Adam is off on a new venture with What Lies Beneath being Book 1in the Rutland series where he bases crime thriller fiction on a real location in the UK. It’s available for pre-order now and out on July 28th, 2020.

The University of Bedfordshire bestowed Adam an Honorary Doctor of Arts for his outstanding contribution to modern literature. As well, Adam has been a regular on the HuffPost, BBC Radio, The Guardian, and The Bookseller. He also hosts a regular podcast called Partners in Crime with fellow bestselling author Robert Daws.

The University of Bedfordshire bestowed Adam an Honorary Doctor of Arts for his outstanding contribution to modern literature. As well, Adam has been a regular on the HuffPost, BBC Radio, The Guardian, and The Bookseller. He also hosts a regular podcast called Partners in Crime with fellow bestselling author Robert Daws.

But, for Kill Zone followers—especially crime thriller writers—Adam Croft has outstanding resources through his Indie Author Mindset books, courses, podcasts, and Facebook Group. Adam states his tipping point as a commercial writer was when he changed his mindset to believe in himself and treat his writing as a professional business.

Obviously, it paid off.

I’ve knocked around in my corner of the entertainment business for a quarter of a century now. Over the years, I’ve seen and heard a lot of snide talk and snobbery among authors and critics that belittles books, films and TV shows for their lack of . . . shall we say importance?

Snottery knows no bounds, it seems. Self-published authors take in on the chin quite a lot, but so do romance authors and those who write cozy mysteries and horror. When speaking a few years ago to a group of students in an MFA program, the professor who introduced me warned the assembled body to have an open mind even though I was “content to write nothing more important than commercial fiction.” If you’ve attended any of my seminars since then, you might remember that I now introduce myself as a writer of commercial fiction, whose work will likely never be taught in the classroom. I consider that to be something of a badge of honor.

I write and I consume the creative works of others for one primary purpose: to entertain or be entertained. Hard stop. If the material I’m consuming also educates, informs or instructs me at the same time, that’s terrific, but it’s not a requirement.

That said, I’m not an easy audience. The classics that I’m supposed to say I love because I make my living as an author–Hemingway, Marquez, Joyce, Fitzgerald, et. al.–for the most part put me to sleep. And Michener. Good God, James Michener. I stipulate that these authors are all brilliant, and that they have changed people’s lives, but I am unable to plow through their stories from beginning to end. Perhaps I’m a lazy reader.

Or perhaps I prefer to read great stories well told in voices that resonate in my head. Give me a Stephen King or Stephen Hunter or Tess Gerritsen or James Scott Bell, put me in a quiet room with a wee dram of smoky scotch, and I will be transported to wherever they take me.

What they write–what we write–may not be important (remember, that’s the word we agreed on), but the works inspire. Powerfully drawn good guys bring justice to powerfully drawn bad guys. Some leave more blood on the ceiling and walls than others, some present more moral ambiguity than others, but after the last page turns, right and wrong are sharply defined.

Last week, my fellow bloggers here at TKZ wrote of old television shows and old comedians. As I read those posts and the responses, it occurred to me that the common trait shared by writers, actors and comedians is a commitment to telling stories that move their respective audiences in some way. That’s what entertainment is, isn’t it?

And it works best when it surprises us. M*A*S*H was primarily a comedy, but who among us didn’t choke up the first time we learned of Henry Blake’s final plane trip? To this day, even though I’ve seen the episode a dozen times or more, the room still gets dusty every time I watch Andy Taylor open the window and tell Opie to listen to those birds that will never see their mama again.

Which brings us to the topic of courage (or lack thereof). Every week, my DVR records episodes of “12 O’Clock High”, starring Robert Lansing as General Frank Savage. I remember watching it as a kid, but all I remember are the scenes of aerial battle. The stories are really very complex and often quite moving. When you consider that the series aired when World War 2 wasn’t yet 20 years in the past, and that more pilots died in the 8th Air Force out of England than did all of the Marines in the Pacific theater, the story lines are particularly courageous. Battle fatigue (PTSD), cowardice, reckless bravery, loss of friends and the futility of war are all addressed in those episodes. They entertain because they resonate, and they resonate because we care about these young men who are forced to take exceptional risks for the benefit of others. We see courage in action. And it’s inspiring.

Which brings us to the topic of courage (or lack thereof). Every week, my DVR records episodes of “12 O’Clock High”, starring Robert Lansing as General Frank Savage. I remember watching it as a kid, but all I remember are the scenes of aerial battle. The stories are really very complex and often quite moving. When you consider that the series aired when World War 2 wasn’t yet 20 years in the past, and that more pilots died in the 8th Air Force out of England than did all of the Marines in the Pacific theater, the story lines are particularly courageous. Battle fatigue (PTSD), cowardice, reckless bravery, loss of friends and the futility of war are all addressed in those episodes. They entertain because they resonate, and they resonate because we care about these young men who are forced to take exceptional risks for the benefit of others. We see courage in action. And it’s inspiring.

Fictional courage–whether on the page or on any size screen–starts with the writer, not with the characters. I tell myself that there are places I won’t go in my work, but that’s really a lie. I’ve harmed children and animals in my books, but never gratuitously. Still, I get hate mail whenever I do, and that’s fine. I figure that I moved that reader, and therefore I did my job. Sure, I moved them in a direction I didn’t intend, but at least they cared enough to write a note.

Plain vanilla stories are always safe, and they’re certainly not important. But if they’re not even inspiring, doesn’t that just make them irrelevant?

So what about you, TKZ family? What risks are you willing to take in your reading and your writing?

By PJ Parrish

We’re off to the hoosegow, the clink, con college, the gray-bar hotel for today’s First Page submission. That much is certain. But I’m gonna need your help on figuring out some of the other things going on here. Please give your time to our writer and don’t be shy about weighing in with some pointers, praise and punditry.

Case Runner

The funny thing is, my folks wanted me to be a lawyer.

It’s a profession. You’ll always make a living. Like Uncle Mike.

That was before Uncle Mike, my father’s older step-brother, went to prison for skimming trusts. He died there, in pretty short order.

After sitting through more of Dad’s drunk disorderly and domestic abuse hearings than I could count, I wasn’t interested in law. I majored in computer science, with a minor in bookmaking, as a runner for Sweet Clete Sojack. I had a little credit card harvesting going on the side: go-go growth businesses practically invited me to grab their transaction data for resale, and in a pinch I could Netstumble my way into wide-open WiFi.

But I was better at getting the info than covering my tracks, so I also did a little time. Unlike Uncle Mike, I not only got out in 18 months, but emerged with a profession, funnily enough related to law, in about the same way as I was related to Uncle Mike.

You can learn a lot of things in prison. Some, a lot, we’ll leave unsaid. But you meet people who see things just a little differently, the spaces between the itch and the scratch where money can be made.

One of these people was Simon Vann, who had been a plaintiffs’ attorney until a case where much of his plaintiff class turned out to have already handed over powers of attorney to out-of-state relatives before signing with him. The houses, the cars, the boat, the sugar on the side, were all gone in a flash. He blamed himself for one thing and one thing only.

“I called the wrong case runner. Tried to save a few bucks.” He waved liver-spotted hands around the prison library. “Worked out great, huh?”

I asked him what a case runner was.

“See, there are laws against an attorney cooking up a cause of action and then finding warm bodies for plaintiffs. They call it ‘champertry’. So there’s a service, kind of a grey area, people who generate leads, finding and referring people whose issues jibe with the theory of the case. For a small fee per head, the attorney gets parties already qualified by the case runner.” Simon stared at the book in his hand, a history of power boats. “He hopes.”

______________________________

I’m back. First off, I really like this writer’s voice. It’s unique, punchy and gives me a pretty decent feel for the narrator’s character — or lack of same. But we need a bit more flesh on the bones, which I will get into in a moment.

This opening is essentially back story. Which is a no-no, yes? Well, not necessarily. What I call character-intro openings can be effective when done well. But the writing must be razor sharp for the reader to be patient and wait for something to happen ie action.

One of the best character openings, which I often cite in workshops, is in Steve Hamilton’s debut A Cold Day In Paradise. He is introducing his series character Alex Knight with this paragraph:

There is a bullet lodged in my chest, less than a centimeter from my heart. I don’t think about it much anymore. It’s just a part of me now. But every once in a while, on a certain kind of night, I remember that bullet. I feel the weight of it inside me. I can feel its metallic hardness. And even though the bullet has been warming inside my body for fourteen years, on a night like this, when it is dark enough and the wind is blowing, the bullet feels as cold as the night itself.

Yes, this is backstory, but the bullet next to heart image is compelling and deeply personal. Here’s another slow backstory character opening that I like, from Tana French:

My father once told me that the most important thing every man should know is what he would die for. If you don’t know that, he said, what are you worth? Nothing. You’re not a man at all. I was thirteen and he was three quarters of the way into a bottle of Gordon’s finest, but hey, good talk. As far as I recall, he was willing to die a) for Ireland, b) for his mother, who had been dead for ten years, and c) to get that bitch Maggie Thatcher.

All the same, at any moment of my life since that day, I could have told you straight off the bat exactly what I would die for. At first it was easy: my family, my girl, my home. Later, for a while, things got more complicated. These days they hold steady, and I like that; it feels like something a man can be proud of. I would die for, in no particular order, my city, my job, and my kid.

Slow, measured, nothing happening here but the character trying to get into our heads. This goes to French’s style. And here is maybe my favorite character-doing-nothing-but thinking opening, from Mike Connelly’s The Poet.

Death is my beat. I make my living from it. I forge my professional relationship on it. I treat it with the passion and precision of an undertaker — somber and sympathetic about it when I’m with the bereaved, a skilled craftsman with it when I’m alone. I’ve always thought the secret to dealing with death was to keep it at arm’s length. That’s the rule. Don’t let it breathe in your face.

But my rule didn’t protect me. When the two detectives came for me and told me about Sean, a cold numbness quickly enveloped me. It was like I was on the other side of the aquarium window. I moved as if underwater — back and forth, back and forth — and looked out at the rest of the world through the glass. From the backseat of their car I could see my eyes in the rearview mirror, flashing each time we passed beneath a streetlight. I recognized the thousand-yard stare I had seen in the eyes of fresh widows I had interviewed over the years.

So yes, you can start by having your character thinking instead of doing. But it damn well better be so compelling that your reader is as well hooked as a fighting marlin. Does the opening to Case Runner succeed? Do you find this Unnamed Man narrator seductive? Does he force you to turn the page?

Well, almost. As I said, the voice has great tone to it. But it lacks the empathy bond that both Connelly and Hamilton forge. Other than the fact Unnamed Man is a bit of wise guy, I don’t get much sense of personality or feel much connection to him. I know that empathy for a character needs to be built over the course of an entire book, but we don’t know quite where we’re going with Unnamed Man here.

And here’s the rub. I think, though I am not sure because the writer isn’t specific enough, that Unnamed Man is going to go to the dark side and become a case runner. Which makes him at best an anti-hero. Will we want to root for him if he’s got the morals of a slug? Is the plot’s trajectory going to create a character arc that has him finding his way back into the light? We can hope.

Couple years ago, Steve Hamilton, on hiatus from his Alex Knight character, started a second series starring an anti-hero named Nick Mason. Here’s the book’s teaser back copy:

Nick Mason is out of prison. After five years inside, he has just been given the one thing a man facing 25-to-life never gets, a second chance. But it comes at a terrible price.

Nick Mason is out of prison, but he’s not free. Whenever his cell phone rings, day or night, he must answer it and follow whatever order he is given. It’s the deal he made with Darius Cole, a criminal kingpin serving a double-life term who still runs an empire from his prison cell.

Forced to commit increasingly more dangerous crimes, hunted by the relentless detective who put him behind bars, and desperate to go straight and rebuild his life with his daughter and ex-wife, Nick will ultimately have to risk everything–his family, his sanity, and even his life–to finally break free.

See the point I am trying to make for our writer? If your guy starts out as a black hat, you need to make us care that he has a chance. He needs a journey, not just of plot but character. Redemption is a powerful theme in fiction. I hope this is where our writer is taking us.

Okay. But we have a basic structure problem beyond that. And it creates confusion. When and where is this scene taking place? After several paragraphs of backstory, in which we learn that Unnamed Man served 18 months in prison and got out, we get the first “action” scene — Unnamed Man talking to Simon Vann. They seem to be in a prison library, so that made me assume that Unnamed Man is also a prisoner. See the problem? The writer told us he was out, yet here we are behind bars. This is not a flashback; it is poor structure. Plus the writer tipped his plot hand too early by revealing in backstory narrative that he emerged from prison ironically with a new profession related to the law.

If the writer wants to stay with this backstory opening, he needs a way to gracefully transition to the PRESENT IN PRISON. Which is where the story really starts. It can be as simple as “I was thinking of my Dad (or Uncle Milt) or whatever, when I walked into the library and saw Simon Vann sitting at a table surrounded by a twelve volumes of The Supreme Court Reporter.

Then have Unnamed Man go over and strike up the conversation. The way it is written is so bare bones we can’t easily figure out what is going on, where we are, and why this encounter is even happening. Give it dramatic context. Has Simon been considering trying to drag Unnamed Man into his case runner scheme? Has Unnamed Man heard that Simon is recruiting? We need context. This is all happening in a plot vacuum.

Now let’s talk about the idea of case running itself. I’ve never heard of it, but then I am not steeped in law or legal thrillers. My sister Kelly knew immediately but she can quote every line of dialogue from Law & Order. If, like me, you didn’t know what a case runner is, could you figure it out from Simon’s description? I’d guess no. Here is what Simon says:

“There are laws against an attorney cooking up a cause of action and then finding warm bodies for plaintiffs. They call it ‘champertry’. So there’s a service, kind of a grey area, people who generate leads, finding and referring people whose issues jibe with the theory of the case. For a small fee per head, the attorney gets parties already qualified by the case runner. He hopes.”

This sounds like something out of Wikipedia, not like a person would really talk. It needs to be filtered through Simon Vann’s particular personality prism. And again, it needs context. Why did this topic even come up? Why are they talking about it? It is just thrown out there with no reason, so why do we care? It needs to be a scene, with logic and dialogue between the two characters.

I found a good lawyer’s site that explains it better than Simon did — which is saying alot considering how bad lawyers are at breaking things down in real English. Essentially, case running is a fancy name for ambulance chasing. Bear with this long explanation because it goes to a point I want to make, again, about character arc:

More often than not, “ambulance chasing” is carried out not by attorneys, but by others known as “runners”. Case runners are not licensed to practice law. Rather, they are hired by accident attorneys to do whatever is necessary to get accident victims to hire a personal injury lawyer. And it doesn’t stop there. After the runner gets the injured accident victim to hire the lawyer, the victim is then coerced into going to a doctor who also works with the runner.

In order for these predatory “runners” to find their prey, they listen to police scanners; offer significant cash bribes to accident victims; they confuse the injured accident victims with false information; and, before an ambulance arrives, offer them rides right from the accident scene to a medical office, where the runner will get paid a handsome “referral fee” by the doctors- thousands of dollars. Sometimes, the runners don’t get to the accident scene in time to lure accident victims away from proper medical care. But that doesn’t stop these runners from harassing accident victims. Hospital workers, ambulance drivers, even police officers will sell these runners your most personal information for hefty prices. Armed with this information, runners and ambulance chasers will visit houses, text, call, and write accident victims until they relent.

Make no mistake about it- hustling cases like this is illegal and unethical. But since there is more money to be made selling accident victims and their personal, private information to the highest bidder than there is selling drugs on the street; the “runners” aren’t running scared. Instead, they are running all the way to the bank.

Wow…really good fodder for a anti-hero plot, right? He’s a sleazy, Better Call Saul type of dude who preys on vulnerable people and sells your personal info on the street to the highest bidder! Now that’s a great start for any character, so kudos to the writer for recognizing this potential.

But…

If Unnamed Man remains a predator throughout the whole book and learns nothing, what happens? We won’t care about him. And that is death to any book.

So, to go back to structure again, this opening really needs a good scene of extended dialogue between Simon Vann and Unnamed Man explaining what a case runner is and it needs to set up the plot catalyst that Unnamed Man is going to the dark side.

Let me do some quick line editing to make a few other points.

The funny thing is, my folks wanted me to be a lawyer. I assume the writer means that it’s ironic that his parents wanted him to be a lawyer but then he became a case running sleazo?

It’s a profession. You’ll always make a living. Like Uncle Mike.

That was before Uncle Mike, my father’s older step-brother, went to prison for skimming trusts. He died there, in pretty short order.

After sitting through more of Dad’s drunk disorderly and domestic abuse hearings than I could count, I wasn’t interested in law. Nice bit of sad backstory, but it could be a tad more personalized. After sitting in the back of too many courtrooms next to my crying mother, watching my dad….I majored in computer science, where? We need to know where this story is taking place and this would drop a hint. with a minor in bookmaking, as a runner for Sweet Clete Sojack. I had a little credit card harvesting going on the side: go-go growth businesses practically invited me to grab their transaction data for resale, and in a pinch I could Netstumble my way into wide-open WiFi. Again, this is nice voice but it’s a little thin. Can we have a hint as to why a guy who made it to college felt compelled to run numbers and steal credit card info? The problem is, you are really setting him up as unlikeable.

But I was better at getting the info than covering my tracks, so I also did a little time. Again, a little thin on telling details. What was he busted for? Can you make it more personal and involving for us? Unlike Uncle Mike, I not only got out in 18 months, but emerged with a profession, funnily enough related to law, in about the same way as I was related to Uncle Mike. On first read, this seems like cheeky good writing. But it is really confusing because in a couple graphs, we’re right back in prison. And, dear writer, you gave away your main plot point too easily. Him emerging from prison with a dark side job is a cool BAM! plot moment. Don’t bury it in a tossed-off narrative comment.

You can learn a lot of things in prison. Some, a lot, we’ll leave unsaid. But you meet people who see things just a little differently, the spaces between the itch and the scratch where money can be made. Syntax problem here. Do you mean they see things just a little clearly, like recognizing that space between the itch…

One of these people was Simon Vann, who had been a plaintiffs’ attorney until a case where much of his plaintiff class turned out to have already handed over powers of attorney to out-of-state relatives before signing with him. The houses, the cars, the boat, the sugar on the side, were all gone in a flash. He blamed himself for one thing and one thing only. How does he know this?

“I called the wrong case runner. Tried to save a few bucks.” He waved liver-spotted hands around the prison library. “Worked out great, huh?”

I asked him what a case runner was. Again, this conversation must have the structure and context of a dramatic scene. Why are they talking about this? You have to slow down and choreograph your scene with more detail and clarity.

“See, there are laws against an attorney cooking up a cause of action and then finding warm bodies for plaintiffs. They call it ‘champertry’. So there’s a service, kind of a grey area, people who generate leads, finding and referring people whose issues jibe with the theory of the case. For a small fee per head, the attorney gets parties already qualified by the case runner.” Simon stared at the book in his hand, a history of power boats. “He hopes.” As I said, the definition of case runner is essential to your book. You have to break down in layman terms, even if it’s coming from the mouth of a lawyer. Remember, Unnammed Man is NOT a lawyer, so he can ask “dumb” questions for the reader. First, figure out a reason for this conversation to be happening, then give us DIALOGUE ie action. Example:

I had heard around the exercise yard that Vann was looking to hire someone to work on the outside. It was big money for little work, rumor was. I was getting out in eight weeks and with my record had no chance of scoring something big in the computer biz.

Simon looked up at me as I approached his table. “I hear you’re looking for work,” he said.

How he had figured that out I’d never know. But I took it for a cue to slide into the chair across from him.

Then start the dialogue about what a case runner is. And your plot and character is off and running.

One last nit. You notice how annoying it was for me to keep using the phrase Unnamed Man? You need to find a way to gracefully tell us your guy’s name and quickly.

So, I hope you find this useful and not too discouraging. As I said, you’ve got some writer chops. You just need to figure out the structure issues and more important, how you want to make us want to root for your guy. Thanks for submitting!

By Sue Coletta

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. My comments will follow.

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. My comments will follow.

The Invisible

Bette always joked Marge’s baking would be their demise—but not like this. The Schuster sisters came out to their garden this morning in search of tomatoes for their weekly Girl’s-Club brunch, and though their basket was nearly full, Bette insisted they needed one or two more.

“What about those?” Marge said, pointing to a large cluster.

Bette tsked. “I’m sure we can do better. Do you want the girls eating green tomatoes? What if it was—?” She stopped mid-sentence, glanced down, and wiped her boot on a rock. “Oh, my,” she chuckled, shaking her head. “Well, if that’s the worse that happens today, I’m counting my blessings.” She continued her search. “What time did Paige get in last night?”

“Well, it was past 9:00—when we went to bed. She rents a room; she doesn’t answer to us.”

“I know that, Marge.” She moved down the row. “I just worry she’s not getting enough sleep.”

“She’s a student. They aren’t supposed to sleep.”

“Who’s not supposed to sleep?”

They looked up to see their boarder, backpack over shoulder, mug of coffee in hand, cut across the dewy lawn. “We were just saying,” Marge said, “that you don’t get enough sleep, dear.”

She laughed. “Can’t argue with that. But my paper’s due Monday, and I’m nervous about it. By the way, was that apple pie I smelled, or am I still dreaming?”

“Oh, my pies! I almost forgot.” Marge squeezed Paige’s arm. “If you wait a few minutes, you can have a piece.”

“It’s tempting, but I really need to get to the library.” She waved to the sisters as she hurried to her car. “Save me a slice.”

“We will, honey. Now don’t work too hard. Remember, life is short.” They watched her head to campus, after which Marge rushed off to check on the pies, promising to be right back.

Bette continued down the rows, her persistence eventually paying off. As she removed an almost perfect Brandywine tomato from its vine, a high-pitched scream split the air. She snapped her head around in time to spot a red-tailed hawk, something squirming in its beak, swoop below the treetops. Her heart was still pounding when a calloused hand grabbed her ankle, causing her to drop the basket. She jerked free, only to discover the hand was an out of control cucumber vine.

Though the sisters seem sweet, not much happens on this first page … unless you’re a research junkie like me and have studied this particular murder weapon. Which is genius, by the way. Kudos to you, Brave Writer. For those who didn’t catch it, I’ll explain in a minute.

Let’s look at your first line, which I liked.

Bette always joked Marge’s baking would be their demise—but not like this.

Your first line makes a promise to the reader, a promise that must be kept and alluded to early on. Just the suggestion of green tomatoes is not enough.

Now, let’s look at the first paragraph…

The Schuster sisters came out to their garden this morning in search of tomatoes for their weekly Girl’s-Club brunch, and though their basket was nearly full, Bette insisted they needed one or two more.

I assume Brave Writer discovered that tomatoes contain a few different toxins. One of which is called tomatine. Tomatine can cause gastrointestinal problems, liver and heart damage. Its highest concentration is in the leaves, stems, and unripened fruit. Red tomatoes only produce low doses of tomatine, but the levels aren’t high enough to kill.

Like other nightshade plants, tomatoes also produce atropine in extremely low doses. Though atropine is a nasty poison, tomatoes don’t produce enough of it to cause death. The most impressive toxin from green tomatoes is solanine. Which, as Brave Writer may have discovered, can be used as murder weapon. Solanine can be found in any part of the plant, including the leaves, tubers, and fruit, and acts as the plant’s natural defenses. People have died from solanine poisoning. It’s also found in potatoes and eggplant.

If Marge eats, say, potato pancakes along with green tomatoes during that brunch, it’ll increase the solanine and other glycoalkaloid levels coursing through her system. *evil cackle*

The nice part of solanine poisoning from a writer’s perspective is that it can take 8-10 hours before the victim is symptomatic, which gives Brave Writer plenty of time to let her stumble into more trouble to keep the reader guessing how or why she died.

If I were writing this story, I’d study the fatal solanine cases and put my own spin on it.

Hope I’m right about this. If not, my apologies. In any case, the weekly Girl’s Club (no hyphen and only capped if it’s the official title of the club) brunch seems important and so do the tomatoes. What I’d love to see on this first page is why. You don’t need to tell us, but you do need to hint at the reason to hold our interest.

What if Bette plucks the deadly fruit from the vine and notices how strange it looks? You’ll have to research to nail down the minute details of a toxic green tomato, if any differences are visible to the naked eye.

There’s one other problem with this first paragraph. Here it is again:

The Schuster sisters came out to their garden this morning in search of tomatoes for their weekly Girl’s-Club brunch, and though their basket was nearly full, Bette insisted they needed one or two more.

Who’s narrating this story? It isn’t Bette, as your first line indicates. And it isn’t Marge. An omniscient point-of-view is tricky to pull off. Newer writers should focus on one main character and show/tell the story through their eyes. If that character doesn’t hear, see, feel, taste, experience, smell, etc. something, then it must be excluded.

Yes, some writers (me included) use dueling protagonists, alternating scenes between the two, and even include an antagonist POV. But when we’re still honing our craft, especially when we’re learning the ins-and-outs of POV, it’s easiest to concentrate on one main character throughout the story. For more on mastering point-of-view, see this post or type in “point of view” in the search box. We’ve discussed this area of craft many times on TKZ.

As written, my advice is to keep the first line and either delete the rest and find a different starting point (sorry!) or better yet, saturate it in mystery regarding these tomatoes. That way, the reader will fear for your main character while the fruit lay on a bed of lettuce on a serving platter during the Girl’s Club meeting. If you choose this route, one of your goals is to make the reader squirm. “Don’t eat that tomato, Marge!”

What say you, TKZers? Please add your gentle and kind advice for this brave writer.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

When Carl Reiner died recently at the age of 98, I pondered again my theory about comedians and their brains. It’s not scientific or scholarly or anything other than my personal observation, but it seems to me that comedians who daily exercise their brains by being funny, often on the spot, resist dementia as they age. Ditto trial lawyers.

I’ve written about this before:

What got me noticing this was watching Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks being interviewed together, riffing off each other. Reiner was 92 at the time, and Brooks a sprightly 88. They were both sharp, fast, funny. Which made me think of George Burns, who was cracking people up right up until he died at 100. (When he was 90, Burns was asked by an interviewer what his doctor thought of his cigar and martini habit. Burns replied, “My doctor died.”)

So why should this be? Obviously because comedians are constantly “on.” They’re calling upon their synapses to look for funny connections, word play, and so on. Bob Hope, Groucho Marx (who was only slowed down by a stroke), and many others fit this profile.

And I’ve known of several lawyers who were going to court in their 80s, still kicking the stuffing out of younger opponents. One of them was the legendary Louis Nizer, whom I got to watch try a case when he was 82. I knew about him because I’d read my dad’s copy of My Life in Court (which is better reading than many a legal thriller). Plus, Mr. Nizer had sent me a personal letter in response to one I sent him, asking him for advice on becoming a trial lawyer.

And there he was, coming to court each day with an assistant and boxes filled with exhibits and documents and other evidence. A trial lawyer has to keep a thousand things in mind—witness testimony, jury response, the Rules of Evidence (which have to be cited in a heartbeat when an objection is made), and so on. Might this explain the mental vitality of octogenarian barristers?

There also seems to be an oral component to my theory. Both comedians and trial lawyers have to be verbal and cogent on the spot. Maybe in addition to creativity time, you ought to get yourself into a good, substantive, face-to-face conversation on occasion. At the very least this will be the opposite of Twitter, which may be reason enough to do it.

In that post I offered a few creativity exercises to help writers keep the brain primed and playful. Today I want to add something else to the list.

I recently came across a scholarly article published a couple of years ago which demonstrated the effect that drawing has on memory.

We propose that drawing improves memory by promoting the integration of elaborative, pictorial, and motor codes, facilitating creation of a context-rich representation. Importantly, the simplicity of this strategy means it can be used by people with cognitive impairments to enhance memory, with preliminary findings suggesting measurable gains in performance in both normally aging individuals and patients with dementia.

So how might drawing operate as an aid to plotting your novel or scene?

Most of you know about mind mapping. Early in my writing journey I read Writing the Natural Way, which teaches mind mapping as a practice for writers. I use it all the time. For example, I was trying to come up with a great big climax to one of my Mallory Caine, Zombie-at-Law novels. I took a walk to Starbucks, got a double espresso, and sat for awhile. Then I took out some paper and starting jotting ideas as they came to me. Here is that paper (the numbers I added later to give me the order of the scenes):

And that’s the ending that’s in the book.

When pre-plotting, I’ll take a yellow legal pad and turn it lengthwise and start mapping. Now I’m thinking about adding drawing to the mix. I don’t have to be a skilled cartoonist (good thing, for that is not one of the gifts bestowed upon me). But I can doodle, have a little fun, and trigger another part of my brain.

If you’re writing a scene with a closed environment, I can see value in making a map of the place—office, city block, house—and drawing the characters (even stick figures will do) as they negotiate the action. It might stimulate new ideas for the scene you wouldn’t get any other way.

Your friend, the brain. It is quite versatile indeed.

What about you? Do you use any visual techniques for your writing or creativity? (I’m on the road today and will check in when I can. Until then, talk amongst yourselves!)

My granddaughter S. went missing for a very short time several years ago.

It happened on a Thursday during the first week of June. S. was a student at a wonderful public elementary school in the Clintonville neighborhood of Columbus. A picnic for the students, teachers, and parents was — and still is — annually held on the school playground during the closing hours of the last day of class. My son J. — her father — took an extended lunch hour from his job and dutifully presented at the time appointed. He was somewhat puzzled when he did not see S. among the students cavorting around the swings. J. approached S.’s teacher and inquired as to her whereabouts. The teacher asked another teacher, who asked another, who asked the school secretary, who asked the principal. Within the course of a few minutes, a hue and cry quietly started up, one that was on the verge of quickly rounding the corner to full-blown hysteria. J., having learned at his father’s knee how to react to an emergency, fought down the tide of his own rising panic and quickly called his neighbor to ask if S. was in sight. The neighbor advised that yes, S. was on J’s front porch, bearing the look of someone who finds themselves in a situation resulting from an action that wasn’t entirely thought through prior to its execution.

It was learned a bit later that S., being a somewhat willful child at that time, had concluded that she had experienced enough school for the year and decided to skip the picnic. She didn’t think to tell anyone about her decision, and with the skill of a Ms. Pac-Man circumvented the carefully maintained school security labyrinth which was in place to keep such a thing from occurring. She then walked the few blocks from her school to her home in order to jumpstart her summer vacation by a couple of hours.

J. told the teachers that S. was at home. Those assembled collectively breathed a sigh of relief. As J. left the school to deal with the wayward S. he heard the name “Kelly Prosser” mentioned as the instructors talked among themselves. He wondered who she was.

Kelly Ann Prosser in 1982 had been an eight-year-old student at a much-acclaimed alternative school in the same neighborhood as my granddaughter’s. The school year was barely three weeks old when Kelly disappeared while walking home. Her body was found two days later in a cornfield located in a quiet community contiguous to Columbus. She had been beaten, raped, and murdered.

Several individuals were questioned by Columbus police detectives but no one was ever charged with Kelly Ann’s murder. J., who was four years old at the time, probably wondered why his parents held him and his younger siblings just a little more tightly and watched them just a bit more closely for the next, oh, thirty-eight years or so (and counting). For the teachers at Kelly Ann’s school, and virtually every school in the area., there was an additional nightmare a-borning. Whoever visited the horrors of Kelly Ann’s final hours upon her was, as far as anyone knew, still out there watching and waiting for another opportunity. While the safety of their students was uppermost in the minds of the teachers and administrators, I suspect that no one wanted to bear the burden of having another such act repeated on or after their watch.

That fear carried over across the decades. The Columbus Police Department, for its part, never gave up on Kelly’s case. Decades passed. Forensic tools were created, improved, and sharpened. The Columbus Police Cold Case Unit, announced on June 26, 2020, that the case had been closed. A DNA sample obtained from material originally gathered at the crime scene conclusively linked her attack and death to one Harold Warren Jarrell. He was no stranger to the criminal justice system. Jarrell had been arrested, tried, convicted, and incarcerated for abducting a little girl in 1977 from another Columbus neighborhood. He was released from prison after five years and had been walking among the innocent and unknowing for but a short time before Kelly Ann’s path crossed his. Jarrell for whatever reason was not considered a suspect in her murder at the time, and at some subsequent point left Columbus, drifting across the country with stops in Florida and Las Vegas among other places, more often than not attracting the attention of law enforcement before moving on rather quickly and without notice. He met his end at some point — how, where, and why is not immediately clear — and thus cannot face justice for Kelly Ann’s murder and the grief that ripples through time across the lives of her family members to this day. Investigations being conducted in other jurisdictions indicate that Jarrell’s horrible misdeeds continued. One can only hope that his end was slow and excruciating, one where any calls for help which he might have made were unanswered at least and mocked at best.

It is people such as Jarrell who cause me to prefer the company of dogs and cats to people. That said, the tenaciousness of the personnel of the Columbus Police Cold Case Unit — with a mighty and timely assist from a forensic genealogical service named AdvancedDNA — restores, at least partially, my faith in humanity.

I am well aware that in the majority of cases of sexual molestation and abuse the victim and the aggressor are known to each other. There is still a sizable group of opportunistic predators who randomly prey upon the innocent. There are tools available to combat them. Most if not all county sheriff departments now provide a sexual offenders’ database on their websites. There is also a smartphone app for iPhones named Offender Locator which I cannot vouch for, but I can for Truthfinder, an Android app that provides sobering information about sex offenders living and working within a given area. You may want to consult this should you or a family member decide to move to a new neighborhood or take things a step further with that new acquaintance who might seem just a tad too friendly with your child. The writers and authors among you may also — and I am not making light of the problem by suggesting this, not at all — use this app as a means of obtaining inspiration for the truly wretched characters in your latest work in progress. The woods, as they say, are full of them. The lambs walk in sunlight and the wolves wait in darkness for one or more to stray into shadow.

Be safe. Be well. Be alert.

You know, some words and phrases are getting on my nerves. Most people would say it is what it is and at the end of the day, let it go. I know, right? But I’ve been doing some online research. There are certain sayings that tick people off. And readers are people, too. You don’t want to turn off your readers with annoying phrases. Just sayin’.

These outstandingly irritating phrases are garnered from various corners of the Web.

Think carefully before you use them in your writing. You may want to save them for your most hateful characters.

Just sayin’. The winner! Nearly everyone hates this redundant phrase. I mean, you’ve already said what you were going to say, right?

Literally. I confess I’ve used this one and thought it was pretty clever – the first time. Then I noticed that word in every novel I picked up – literally.

It is what it is. Arggh! This meaningless phrase is enough to send me screaming into the night. I admit I’m a little touchy these days, with the quarantine and all, but please don’t use it.

At this moment in time. What’s wrong with “now”? Can this pretentious phrase.

Everything happens for a reason. Usually said after some meaningless tragedy, and meant as consolation. If you don’t have that comforting belief system, this phrase triggers an urge to slap that person silly. Also avoid this phrase: Whenever God closes a door, he opens a window. I had a roommate like that. Very annoying.

Honestly. Often a trigger word indicating the person using it is lying. Use it carefully.

My bad. A cutesy way of glossing over a mistake. This phrase says, “I know I did something offensive and I don’t care.”

I want 110 percent. Right, boss. Except your math doesn’t add up.

No worries. Some people find this phrase a little passive-aggressive. In other words, when someone says, “No worries,” they’re really telling you that you should be worried.

At the end of day. As in, “At the end of the day, getting a new CEO won’t make any difference. This company is doomed.” This crutch will cripple any sentence.

With all due respect. The warm-up to an insult. “With all due respect, even in your prime you weren’t that good.”

That’s my list, and it’s pretty good, in IMHO (oops, there’s another one.) Now’s your chance. What tired words and phrases would you like to see retired?

##########################################################

A Star Is Dead, my new Angela Richman death investigator mystery “will satisfy procedural and cozy fans who like a good puzzle,” says Booklist magazine.

A Star Is Dead, my new Angela Richman death investigator mystery “will satisfy procedural and cozy fans who like a good puzzle,” says Booklist magazine.

Buy it here: https://tinyurl.com/yc6

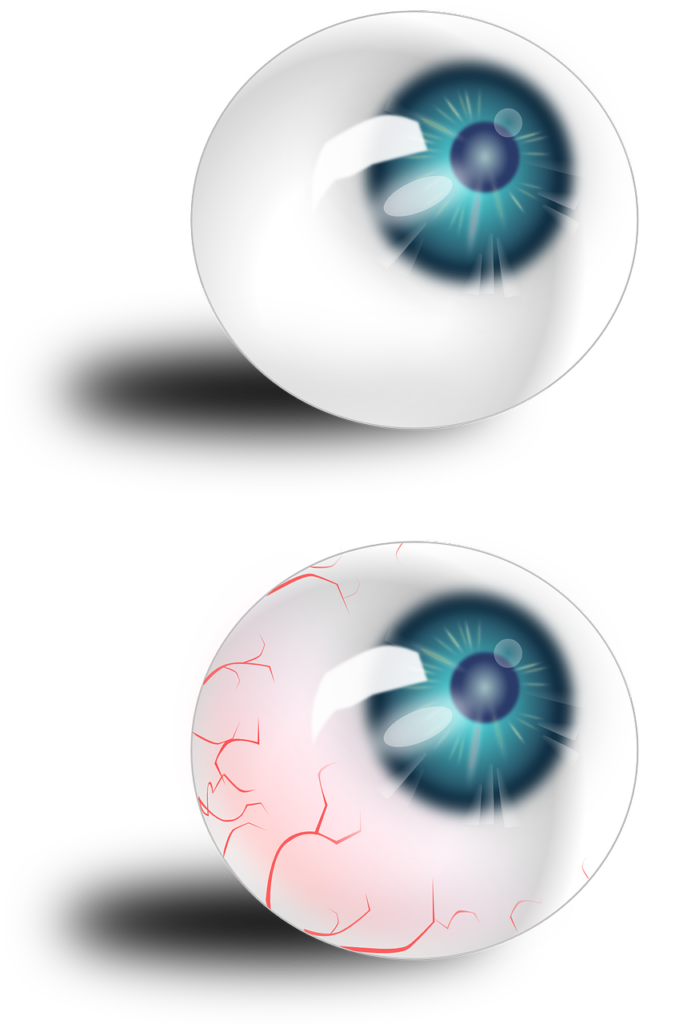

Roaming Body Parts

Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

I recently read a blog with a firm stance on how to deal with body parts. I don’t entirely agree. I don’t have trouble with figures of speech, and if I’m reading that a character ‘flew down the block to John’s house’ I don’t see her mid-air. If someone writes “a lump of ice settled in her belly” I’m not seeing actual ice.

How do you react when you read things like this?

Their eyes met from across the room.

His eyes raked her body from head to toe.

There seem to be two schools of thought on this one. I’m on the side that doesn’t mind. I understand that ‘eye’ can be used as a noun or a verb. “He eyed her” is acceptable. “He gave her the eye” is an idiom I have no trouble with. I don’t see him extracting an eyeball and handing it to her. So if a characters eyes move, I don’t get visions of eyeballs floating free. Others would substitute the word “gaze.” I’ll use either.

Which side are you on? Would the following pull you out of the story?

Her blue eyes, enlarged by her wire-rimmed glasses, rambled from Colleen’s head to her toes.

“What’s wrong with my face?” Her fingers flew to her cheeks.

Yet there are those for whom those would be book-tossing offenses. Me, I see the eye movement in the first example, but the eyes remain firmly set in their sockets. In the second, my brain assumes the fingers are still attached to the hand, and I don’t think about body parts floating in space.

If you give someone the eye, are you handing them an eyeball? Or if a character eyes the room as he enters, what’s he doing? Eye is a verb as well as a noun, after all. And as a verb, my Synonym Finder (great reference book, by the way) lists view, see, behold, catch sight of, look at. And what about all those expressions using ‘eye’? In a pig’s eye. Do we put things into the eye of that pig? Or, keep an eye out for. Do we take an eyeball out and hold it until someone comes for it?

If we took everything we read literally, a lot of the richness of the language would be lost. If his eyes are pools of molten chocolate, do we really think that he’s got Godiva eyeballs? Or just deep brown eyes?

(That’s a metaphor, I think – if his eyes look like pools of molten chocolate, that would be a simile, right?) I’ve never been good at remembering terminology. Metaphors, similes, idioms, hyperbole—they’re things I use, but I don’t worry about what they’re called when I’m writing them.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.