by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Remember the Dionne Warwick song “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?” I always chortled at that. It’s about someone who grew up in San Jose, came down to L.A. to make it in the movie biz, and now wants to go back home. So she asks, “Do you know the way to San Jose? I’ve been away so long…”

Remember the Dionne Warwick song “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?” I always chortled at that. It’s about someone who grew up in San Jose, came down to L.A. to make it in the movie biz, and now wants to go back home. So she asks, “Do you know the way to San Jose? I’ve been away so long…”

Wait, what? You don’t know the way back to your own home town? Sheesh! This is California. You get on the 101 and head north and keep driving till you see a sign that says SAN JOSE, NEXT EXIT.

How hard is that? You’ve got to know enough not to head south toward San Diego! Or you shouldn’t be driving.

Besides, it’s hard to rhyme with San Diego.

Do you know the way to San Diego?

Which way do I point my Winnebago?

Ahem.

My post today was inspired by Brother Gilstrap’s recent thought-provoker, which has the following:

As for plot, I have to know where I am going before I start–or at least before I get too deeply into the story. What I discover along the way is the most fun route to take me there. It’s like knowing you want to drive from DC to Los Angeles, but not knowing till somewhere in Indiana whether you want to take the southern route or the northern route. Or, maybe you want to park at a train station and finish the trip by rail.

This is similar to Isaac Asimov’s practice. He said he liked to know his ending, or at least a rough idea of it, and then have “the fun” of finding out how to get there.

Fun is good. It creates energy. It shows up on the page.

So let me suggest how to up the fun factor in a way that will please both plotter and pantser. (And they said it couldn’t be done!)

This post is a long one. Pack a lunch.

Plotting for Pantsers

Now, don’t get the hives, pantsing friend! You probably think of an outline as some gargantuan document that locks every scene into a cold, heartless shape that you cannot undo.

Nay, not so. I’m going to offer a method that will make outlining just as fun—and ultimately more productive—than pure pantsing.

It’s based on what I call signpost scenes. (For a full account of signpost scenes, I shamelessly refer you to my book Super Structure. But it is not essential for purposes of this post. We now return you to our regularly scheduled blog.) I’m going to suggest that you brainstorm three—just three—signpost scenes as the basis of your plotting. Here they are:

- The Disturbance

This is your opening. This is your hook. This is what will often make or break the sale of your book. We have talked many, many times here at TKZ about that first page. You might want to search for “First Page” and look at some of our critiques. But definitely read Kris’s post on what makes a great opening.

Now, sketch out your first scene. If you want to write it, go for it! I love writing openings that grab readers by the lapels. But you can also sketch it out in summary form. Or do a little of both. Then rework and reshape that summary until it you see the scene vividly in your head.

See that? You’re outlining! Whee!

- The Final Battle

That’s right. Come up with a rip-snorting ending!

PANTSER: But wait. I don’t have any idea what the plot is, let alone the villain!

ME: Who cares? You’re a doggone pantser, right? So pants! Just start playing with a big, climactic scene. Let it suggest to you what the story is about. Play around with this sketch. See it in your mind, like a movie. Then have the actors do it again, only bigger and more exciting.

Don’t get the cold sweats! Listen: You can tweak or change this scene all you want as you write your draft. But having this scene in mind gives you something to write toward.

Often—quite often, actually—I’ll have an ending and villain in mind, and a concluding final battle, but will change the actual villain near the end. You know what that’s called? A twist ending!

So now you have a gripping opening and a slam-bang ending, the essential bookends of an outline.

See how fun this is?

- Mirror Moment

How long does it typically take you, pantser, to know what your story is really about? It varies, right? You may catch it early, or you may not know it until the end of a draft. Or you may finish a draft and sit back and ask, “So what’s really going on here? How can I make it better?”

Why not figure it out from the get-go with a mirror moment?

This idea occurred to me as I studied the midpoint of great movies and popular novels. (I once again shamelessly declare that I wrote in depth about this in my book Write Your Novel From the Middle. But you can get the gist of the idea by reading this post and this other post, so I won’t go over that same ground.)

Brainstorm at least five possible mirror moments. What is your Lead forced to confront about himself in the dead center of the action? One of the ideas you come up with will resonate. It will feel right. And then when you start pantsing in earnest (assuming Ernest doesn’t mind) you will have a through-line that gives all your scenes an almost magical cohesion. And that is really fun.

Now that you’ve got the big three signposts done—that wasn’t so hard, was it?—I suggest you brainstorm a bunch of killer scenes.

What is a killer scene? One that is stuffed with conflict and suspense. One that a reader will be unable to tear his eyes from. Let your boys in the basement start sending them up (the boys love to do that!)

I used to take a stack of 3×5 cards to Starbucks, quaff my joe and come up with 20-25 killer scene ideas. I’d shuffle the cards and look at them and choose the ten best ones. Then I’d ask myself where those scenes might best fit—the beginning, middle, or end? (Gee, sounds like the 3-Act structure, doesn’t it?) I do the same thing now, only in Scrivener (more on that, below).

Pantsers, making up killer scenes on the fly is right in your wheelhouse! You should love it.

Then you can sit back and assess your burgeoning plot outline. Want to change something? Do more cards. You are testing different plot directions without locking yourself into a full draft. Listen to what one former pantser says:

Honestly, I had a hard time believing [outlining is fun] myself until I really got the hang of planning. But really? Planning can be really fun. It allows you to explore all the scenarios and opportunities without having to deal with pages and pages of rewrites.

Imagine a character at a crossroads. Turn left for good, turn right for evil. Up for adventure. Down for home. Which way do they go?

If the author was pantsing, they would have to pick one, follow it, and see where it ultimately leads. This could wind up being a brilliant book, or it could lead to fifty pages of useless material when they realize they would’ve preferred to take a different way.

But not so in planning. In planning, it’s easy to list out every possibility, follow every whim and feel out every thread. It’s possible to try out the wildest storylines and test out ridiculous theories just to see how they pan out. And since you don’t write them until after you’ve planned, you won’t waste time rewriting scenes if, in advance, you see that they won’t work out.

View planning a novel as a time to explore and indulge in all the silly whims you have about your book. Get your ideas out, and then decide which ones make the pages.

After all, what happens in the book plan stays in the book plan.

Pantsing for Plotters

The same method given above will work for you, plotting friend, as you begin to lay out your scenes. Let yourself have fun pantsing your outline, playing with it with the same wild abandon as your pantsing buddies, being free to change things up before you start the long drive of a first draft.

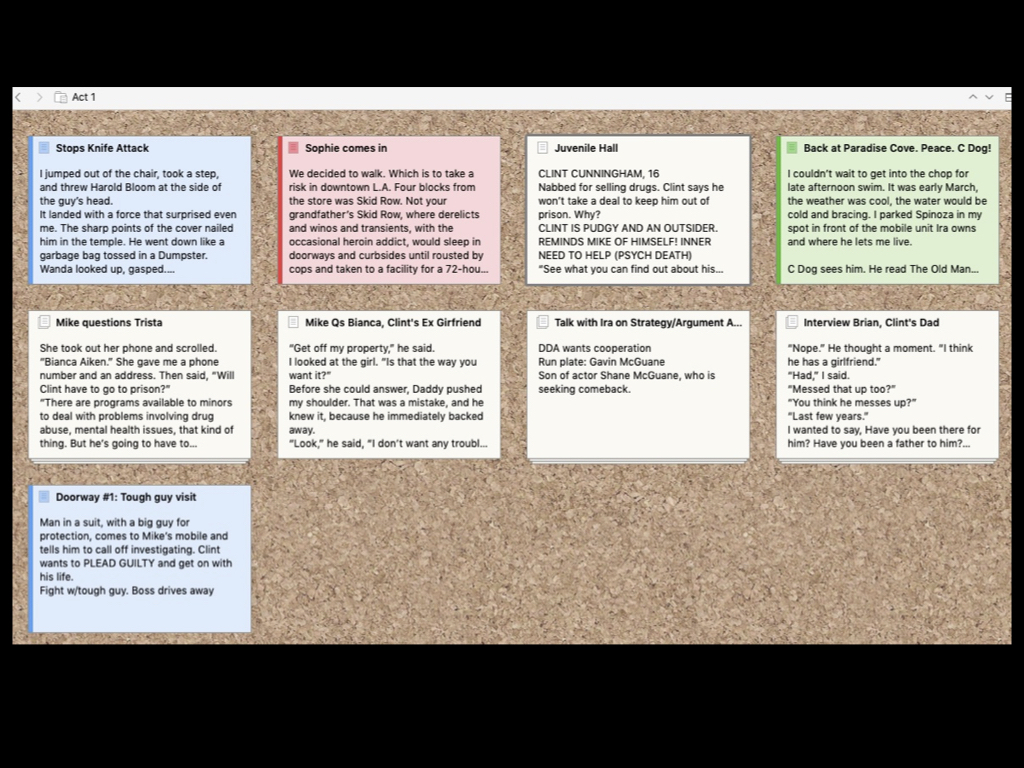

You are more structure-oriented than the pure pantser, so go ahead and lay out your cards with that in mind. I do my plotting on 3×5 index cards. As I mentioned, I do this on Scrivener. My beginning template is made up of my signpost scene cards, waiting to be filled in. I then add scene cards in between as I come up with ideas. I love looking at my growing outline on the Scrivener corkboard, being fee to move the cards around as I see fit. (I know many of you have looked at Scrivener and thought it too complicated to learn, etc. But if you just use it for the corkboard feature, I think it’s worth it. You can learn other bells and whistles later.)

My cards have a title, so I know what the scene is about at a glance. The card itself can hold a synopsis of the scene, or a big chunk of the potential scene. I often write some dialogue for the scene, because it’s fun. I transfer that to the scene card.

Here’s the corkboard for Act 1 of Romeo’s Town:

At this point in the process, I’m just concentrating on the most important scenes. I’m not thinking about transitions or subplots or style. I’m thinking about getting down the big picture of a plot that will deliver the goods.

In days, or maybe a week, I have all these scene synopses. Scrivener lets you print these out so you can sit down and, in just a few minutes, assess your about-to-be-hatched novel.

Need to change anything? Maybe a lot? Maybe the whole book? No problem! You’re not locked into anything. You can try out another route to San Jose! And another.

Whew! That’s quite enough for one Sunday.

Let me leave you with this advice: try something new in your methodology every now and again. Explore other approaches. Give a new idea a whirl. You may be pleasantly surprised at what you find.

Enjoy the drive.

Congratulations! You won an all-expense[s]-paid trip to the location of the last book you read or are currently reading.

Congratulations! You won an all-expense[s]-paid trip to the location of the last book you read or are currently reading.

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. Enjoy! I’ll catch ya on the flip side.

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. Enjoy! I’ll catch ya on the flip side.

conflict. This is usually the first lesson a young writer learns, and rightly so. No conflict, no story. No conflict, no interest. Maybe you can skate along for a page or two with a quirky character, but said character will soon wear out his welcome if not confronted with some sort of disturbance, threat, or opposition.

conflict. This is usually the first lesson a young writer learns, and rightly so. No conflict, no story. No conflict, no interest. Maybe you can skate along for a page or two with a quirky character, but said character will soon wear out his welcome if not confronted with some sort of disturbance, threat, or opposition.

Congratulations! Big shot producer turned your writing life into a game show.

Congratulations! Big shot producer turned your writing life into a game show.