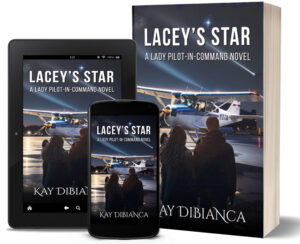

I’m at the tail end of revising my cozy mystery (AKA “crunch time”), having gone over the helpful feedback from my beta readers, and preparing the novel for my copy editor, which inspired today’s trifecta of Words of Wisdom from the Killzone archives. Not only is what we write read by book buyers and library patrons, but our fiction can also be read by fellow writers in a critique group, and by copy editors going over our novels before publication.

First up is an excerpt from James Scott Bell’s 2015 post on The Five Laws of Readers, followed by another 2015 excerpt, this one from Debbie Burke on critique groups, and finishing with one from John Gilstrap’s 2019 post which provides a rundown on copy editing.

As always, check out the full posts, which are date-linked at the end of their respective excerpts.

- The reader wants to be transported into a dream

Fiction writers often hear from agents and editors that a reader wants an “emotional experience” from a novel. Or to be “entertained.”

True, but I don’t think those go far enough. What a reader really and truly longs for is to be entranced. I mean that quite literally. The best reading and movie-going experiences you’ve ever had have been those where you forgot you were reading or watching, and were just so caught up in the story it was like you were in a dream.

It’s like one of my favorite shows as a kid, Gumby. Remember Gumby and Pokey? (If you want to keep your age a secret, don’t raise your hand).

My favorite part of any episode was when Gumby and his horse jumped into a book, got sucked inside, and became part of the story world. I wanted to do that with the Hardy Boys. Jump in and help Frank and Joe solve the mystery.

The point is, when you read, you want to feel like Gumby, like you’re inside the story, experiencing it directly.

Hard to do, writer friend, but who said great writing was easy? Maybe a vanity press or two, but that’s it.

When I teach workshops I often use the metaphor of speed bumps. You drive along on a beautiful stretch of road, looking at the lovely scenery, and you “forget” that you’re driving. But if you hit a speed bump, you’re taken out of that experience for a moment. Too many of those moments and your drive becomes unpleasant.

One reason we study the craft is to learn to eliminate speed bumps, so the readers can forget they’re driving and just enjoy the ride.

- The reader is always looking for the best entertainment bang for the buck

In this, readers are like any other consumer. If they are going to lay out discretionary funds on something, they want a good return on that investment. Their judgment is based on expectations and experience. If they have experienced a writer giving them wonderful reading over and over, they will pay a higher price for their next book.

If, on the other hand, a writer is new and untested, the reader wants a sampling at a low price, or free. Even then, however, they desire to be just as entertained as if they shelled out ten or twenty bucks for a Harlan Coben or a Debbie Macomber.

That’s a challenge all right, and should be. But here’s the good news. If a reader gets something on the cheap and it enraptures them, you are on your way to a career, because of #3, below.

- If you surpass reader expectations, they will reward you by becoming fans

Fans are the best thing to have. Fans generate word of mouth. Fans stay with you.

So your goal needs to be not just to meet reader expectations, but surpass them.

How?

By doing everything you can to get better, write better. To do what Red Smith (and NOT Ernest Hemingway) said. You just sit down at the keyboard, open a vein, and bleed.

That’s not just romanticized jargon. It’s what the best writers do, over and over again.

So what if you don’t reach that high standard with your book? No matter. You book will be better for the trying, and you’ll be a better writer, and you next book will be better yet.

Jump on that train, and stay on it.

James Scott Bell—January 18, 2015

What are critique group strengths?

Support – A CG provides much-needed camaraderie in this oft-lonely business. They throw us a lifeline when we get discouraged, nag us when we’re slacking off, and lend a shoulder to cry on when we receive rejections. They serve as our cheerleaders, therapists, and comrades in the trenches. They’re the first ones to open champagne for our successes. CG members are not only writing colleagues, they often become close friends. We develop a high level of trust and respect for each other, both professionally and personally.

Brainstorming – Here, critique groups really shine. If two heads are better than one, six or eight heads are exponentially better at throwing out suggestions. Feeding off each others energies and ideas, CGs solve many dilemmas that stymy a writer. I can’t count the number of dead ends CGs helped me work through.

Accountability – CGs exert pressure, either subtle or overt, to produce a certain number of pages for each session. They act as a de facto deadline for writers who don’t yet have an editor or agent breathing down their neck. If you show up empty-handed, you’re not meeting your obligation. Dozens of times, I’ve heard writers say, “I wouldn’t have written anything this week, except I needed to submit to the group.”

What are some CG limitations?

Diagnosis – CGs generally do a good job of homing in on a manuscript’s weak spots. If two or more people mark the same passage, you should pay attention. But while they recognize there is a problem, they can’t always diagnose exactly what it is or how to fix it. If CG suggestions don’t help enough, consultation with a developmental editor may be worthwhile.

Overlapping relationships – CG friendships may cloud our judgment of the story. A member of my group, psychologist Ann Minnett (author of Burden of Breath and Serita’s Shelf Life) recently offered a perceptive observation: “When I read A’s chapter, I hear her voice and accent. When I read B’s chapter, I think of her sense of humor, and can’t help but laugh.”

Which made me wonder…Does your CG like your story or do they like you?

When you’re face-to-face with your friends, you hear her charming British accent, see his playful wink. However, when a book is published, most readers will never meet the author, meaning the words must shoulder all the work. They need to be effective by themselves, without explanation or amplification.

Here is where online CGs might give a clearer, more “book-like” perspective. Without personal, visual, or auditory cues, their effort focuses entirely on the words.

Time constraints – My CG meets every two weeks, submitting 15-20 pages per session. At that rate, reviewing a novel-length manuscript takes six months to a year. By the time the group reaches the climactic chapter on page 365, no one remembers a subtle, but important, clue on page 48 that set up the surprise twist. This piecemeal approach is the most vexing limitation I’ve experienced with CGs.

Micro vs. Macro View – A corollary to the time constraint problem is the micro view by a CG. They examine your 20 pages per week and help polish each passage till it shines. When you string all these perfect chapters together, the resulting book should be excellent. Right?

Not necessarily. Close examination under the CG microscope may not adequately address global issues of plot development, pace, and momentum that require a macro view from an airplane.

Debbie Burke—November 17, 2015

Appropriate use of commas seems random to me and the commas themselves complicate language. For example, the copy editor changed this sentence to include commas that I did not: “He and his brother, Geoff, were being driven . . .” To my eye and ear, the meaning is clear without the commas, but I let it go because they tell me they’re correct. (That comma before but shouldn’t be there either, should it?)

Then there’s this edit: “. . . scrolled through his contacts list, and pressed a button.” Why? What does that comma do that its absence does not? Aargh!

Comma Splices

First of all, I didn’t know that a comma splice was even a thing. Here’s the note, verbatim, from the copy editor:

“There are some comma splices in the book, where two complete thoughts, that is, separate sentences, are separated by commas rather than periods. Some people accept this in dialogue but not in descriptive text. I have highlighted those I found like this (word-comma-word highlighted) so you can see where they are and decide what to do. In many cases, the comma splice can be fixed by adding “and” or “but” after the comma.”

Here’s an example of what he’s talking about: “Questions never changed bad news, they only slowed it down.” For me, it’s about the rhythm of the sentence and I think the passage flows better with the comma instead of a period. Apparently, I do this quite a lot. In most cases, I kept the passages as I originally wrote them.

Another example: “Their mom was just arrested, their dad is dead.” The “and” is silent and I think the sentence is better for it.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I clearly need a good copy editor, and this one (the same as I had for Total Mayhem) is very good. He’s just going to have to get used to me not comprehending the role of the comma.

With every set of copy edits, I also receive a “style sheet” that gets deeply into the weeds of my writing style, and that of the publisher. The sections of the style sheet include:

Characters (in order of appearance). With each character comes a brief description, based upon what I wrote in the book. Here’s an example: Soren Lightwater: head of Shenandoah Station, smoker’s voice, mid-forties, built like a farmer, more attractive than her voice;

Geographic Locales (in alphabetical order). Here again, there’s a brief description of the role the location plays in the story. For example: “Resurrection House/Rez House, in Fisherman’s Cove, on Church Street, up the hill from Saint Kate’s Catholic Church, on the grounds of Jonathan’s childhood mansion;

Words Particular to Text. Examples include A/V (audio-visual), ain’t, Air Force One, all-or-nothing deal, asshats . . .

John Gilstrap—November 20, 2019

***

- What else do fiction readers want? How much do you think about what readers want when putting together a story or a novel?

- Have you been in a critique group? Any tips?

- If you use a copy editor, what sorts of things do they help you with, beyond catching typos and missing words?

Back in 2015, I was chatting with a dear writer friend, Paul Dale Anderson, about the different types of writers and readers.

Back in 2015, I was chatting with a dear writer friend, Paul Dale Anderson, about the different types of writers and readers.

My world no longer looks like an Impressionist painting. I can see individual leaves on trees, blades of grass, street signs (oh, that’s where I was supposed to turn).

My world no longer looks like an Impressionist painting. I can see individual leaves on trees, blades of grass, street signs (oh, that’s where I was supposed to turn).

Congratulations! You won an all-expense[s]-paid trip to the location of the last book you read or are currently reading.

Congratulations! You won an all-expense[s]-paid trip to the location of the last book you read or are currently reading.

P.J. Parrish (Kris Montee):

P.J. Parrish (Kris Montee):