Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

If a filler word serves a purpose, keep it. The objective is to tighten the writing by eliminating unnecessary words and anything the reader might find distracting.

For example, a Bigshot Author I adore had the strangest writing tick in her debut novel. It’s a good thing I unknowingly started with book 5, or I might not have devoured two of her thriller series. I can’t tell you her name, but I will share the tic.

“Blah, blah, blah,” she said, and then, “Blah, blah, blah.”

“Blah, blah, blah,” he replied, and then, “Blah, blah, blah.”

Almost every line of dialogue had “she said, and then.” The writing tic distracted me, yanked me right out of the story, and made me want to whip my Kindle out the window. To this day I recall favorite passages from many of her high-octane thrillers, but I couldn’t tell you the basic plot of her debut till I jumped over to Amazon to refresh my memory. She’s since re-edited the novel. 🙂

FILLER WORDS

Just

Just should almost always be murdered.

Original: I just couldn’t say goodbye.

Rewrite: I couldn’t bear to say goodbye.

That

That litters many first drafts, but it can often be killed without any harm to the original sentence.

Original: I believe that all writers kill their darlings.

Rewrite: I believe all writers kill their darlings.

The original and rewrite have another problem. Did you catch it?

Believe in this context is a telling word. Any time we tell the reader things like “I thought” or “He knew” or “She felt” or “I believe” we slip out of deep POV. Thus, the little darling must die.

Final Rewrite: All writers kill their darlings.

So

Original: So, this huge guy glared at me in the coffee line.

Rewrite: This musclebound, no-necked guy glared at me in the coffee line.

Confession? I use “so” all the time IRL. It’s also one of the (many) writing tics I search for in my work. The only exception to killing this (or any other) filler word is if it’s used with purpose, like as a character cue word.

Really

Original: She broke up with him. He still really loved her.

Sometimes removing filler means combining/rewording sentences.

Rewrite: When she severed their relationship, his heart stalled.

Very

Here’s another meaningless word. Kill it on sight.

Original: He made me very happy.

Rewrite: When he neared, my skin tingled.

Of

To determine if “of” is needed read the sentence with and without it. Does it still make sense? Yes? Kill it. No? Keep it.

Original: She bolted out of the door.

Rewrite: She bolted out the door.

Up (with certain actions)

Original: He rose up from the table.

Rewrite: He rose from the table.

Original: He stood up tall.

Rewrite: He stood tall.

Down (with certain actions)

Original: He sat down on the couch.

Rewrite: He sat on the couch.

Original: He laid down the blanket.

Rewrite: He laid the blanket on the floor.

And/But (to start a sentence)

I’m not saying we should never use “and” or “but” to start a sentence, though editors might disagree. 🙂 Don’t overdo it.

Original: He died. And I’m heartbroken.

Rewrite: When he died, my soul shattered.

Also search for places where “but” is used to connect two sentences. Can you combine them into one without losing the meaning?

Original: He moved out of state, but I miss him. He was the most caring man I’d ever met.

Rewrite: The most caring man I’d ever met moved out of state. I miss him—miss us.

Want(ed)

Want/wanted is another telling word. It must die to preserve deep POV.

Original: I really wanted the chocolate cake.

Substitute with a strong verb.

Rewrite: I drooled over the chocolate cake. One bite. What could it hurt?

Came/Went

Came/went is filler because it’s not specific. Substitute with an a strong verb.

Original: I went to the store to buy my favorite ice cream.

Rewrite: I raced to Marco’s General Store to buy salted caramel ice cream, my tastebuds cheering me on.

Had

Too many had words give the impression the action took place prior to the main storyline. As a guide, used once in a sentence puts the action in past tense. Twice is repetitive and clutters the writing. Also, if it’s clear the action is in the past, it can often be omitted.

Original: I had gazed at the painting for hours and the eyes didn’t move.

Rewrite: For hours I gazed at the painting and the eyes never wavered.

Well (to start a sentence)

Original: Well, the homecoming queen made it to the dance, but the king didn’t.

Rewrite: The homecoming queen attended the dance, stag.

Basically/Literally

Original: I basically/literally had to drag her out of the bar by her hair.

Rewrite: I dragged her out of the bar by the hair.

Actually

Original: Actually, I did mind.

Rewrite: I minded.

Highly

Original: She was highly annoyed by his presence.

Rewrite: His presence irked her.

Or: His presence infuriated her.

Totally

Original: I totally did not understand a word.

Rewrite: Huh? *kidding* I did not understand one word.

Simply

Original: Dad simply told her to stop.

Rewrite: Dad wagged his head, and she stopped.

Anyway (to start a sentence)

Original: Anyway, I hope you laughed, loved, and lazed during the holiday season.

Rewrite: Hope you laughed, loved, and lazed during the holiday season.

FILLER PHRASES

As with all craft “rules,” exceptions exist. Nonetheless, comb through your first draft and see if you’ve used these phrases for a reason, like characterization. If you haven’t, they must die. It’s even more important to delete filler words and phrases if you’re still developing your voice.

A bit

Original: The movie was a bit intense. Lots of blood.

Rewrite: Intense movie. Blood galore.

There is no doubt that

Original: There is no doubt that the Pats will move on to the playoffs.

Rewrite: No doubt the Pats will move on to the playoffs.

Or: The Pats will be in the playoffs.

The reason is that

Original: The reason is that I said you can’t go.

Rewrite: Because I said so, that’s why. (shout-out to moms!)

The question as to whether

Original: The question as to whether the moon will rise again is irrelevant.

Rewrite: Whether the moon will rise again is irrelevant.

Whether or not

Original: Whether or not you agree is not my problem.

Rewrite: Whether you agree is not my problem.

Tempted to say

Original: I am tempted to say how beautiful you are.

Rewrite: You’re beautiful.

This is a topic that

Original: This is a topic that is close to my heart.

Rewrite: This topic is close to my heart.

Believe me (to start a sentence)

Original: Believe me, I wasn’t there.

Rewrite: I wasn’t there.

In spite of the fact

Original: In spite of the fact that he said he loved you, he’s married.

Rewrite: Although he professed his love, he’s married.

Or: Despite that he said he loved you, he’s married.

The fact that

Original: The fact that he has not succeeded means he can’t do the job.

Rewrite: His failure proves he can’t do the job.

I might add

Original: I might add, your attitude needs adjusting, young lady.

Rewrite: Someone’s panties are in a bunch. *kidding* Adjust your attitude, young lady.

In order to

Original: In order to pay bills online, you need internet access.

Rewrite: To pay bills online you need internet access.

At the end of the day

Original: At the end of the day, we’re all human.

Rewrite: In the end, we’re all human.

Or: In conclusion, we’re all human.

Or: We’re all human.

Over to you, TKZers. Please add filler words/phrases that I missed. I’m hoping this list will help Brave Writers before they submit first pages for critique.

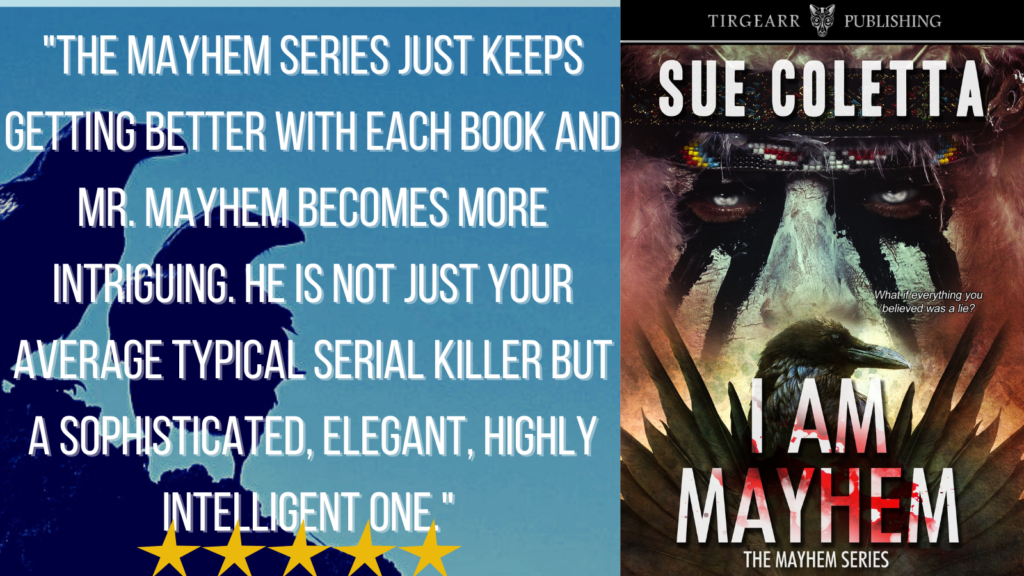

“I did not think this series could become more compelling, oh how wrong I was! Coletta delivers shock after shock and spiraling twists and turns that you will never see coming. I was glued to the pages, unable to stop reading.”

Look Inside ? https://buff.ly/3hmev0C

Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite.

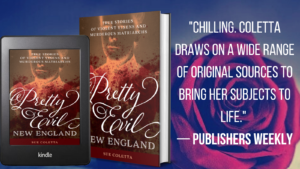

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite. Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime,

Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime,  The holiday season is a hectic time, with planning the perfect family celebration, shopping for gifts, decorating the house, inside and out, and mailing cards.

The holiday season is a hectic time, with planning the perfect family celebration, shopping for gifts, decorating the house, inside and out, and mailing cards. My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

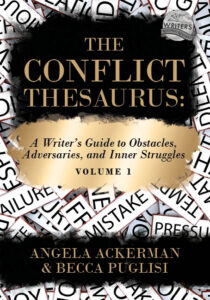

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers.

A recent conversation with my husband brought up two important points for writers to keep in mind. Rather than tell you, I’ll peel back the veil and let you eavesdrop.

A recent conversation with my husband brought up two important points for writers to keep in mind. Rather than tell you, I’ll peel back the veil and let you eavesdrop.

Can a body fit in your car trunk?

Can a body fit in your car trunk?

There was more. While the person was defrosting, the pathologist has to check the body every two hours. The hands and feet would probably defrost first, and then the pathologist could get scrapings from under the nails. As the defrosting progressed, the pathologist would draw blood and get fluids, including ocular fluid from the eyes, and if the person was a woman, check for seminal fluid in the vaginal vault.

There was more. While the person was defrosting, the pathologist has to check the body every two hours. The hands and feet would probably defrost first, and then the pathologist could get scrapings from under the nails. As the defrosting progressed, the pathologist would draw blood and get fluids, including ocular fluid from the eyes, and if the person was a woman, check for seminal fluid in the vaginal vault.

Now in audio! All my Angela Richman mysteries and the first three Dead-End Job novels. Listen to them during your 30-day free trial with Scribd.

Now in audio! All my Angela Richman mysteries and the first three Dead-End Job novels. Listen to them during your 30-day free trial with Scribd.