Photo by Laura Benedict.

Cheery good day, TKZers! It’s time for a critique of an anonymous author’s work. The Last White Rose is an excerpt from a novel that appears to be a modern gothic with both horror and romantic elements. But it might be a thriller. I’m anxious to know what you think.

THE LAST WHITE ROSE

Epigraph

In my dream, I see my own green eyes, filled with terror and tears.I fall to my knees, submitting to the command of invincible blue eyes raging with white fire.His face twists into something else, something evil. He is ending my life. I wake with a strident scream… and stare into the same blue eyes.

Chapter One

Stonington, Connecticut

He was elusive, a ghost I needed to catch. The stranger whose face I’d never seen lurked around town, maintaining enough distance to mask his features in shadow. I saw his face for the first time in late July after the annual Blessing of the Fleet. His bold gaze burned into mine from the opposite side of Water Street. The highland band, piping loud and marching through the center, drew the post-ceremony procession to a close, granting me an unobstructed view.

A shiver slid through me despite the stifling summer heat.

He was magnificent. The kind of man you’d never find living in small-town New England. Imposing height and broad, muscled shoulders defined his stature. He wore jeans and a faded indigo tee shirt that exposed cut biceps and forearms. Sun-streaked, dark blond hair in a classic front wave and a commanding jawline framed his handsome, smirking face.

“Parade’s over,” someone shouted.

Even so, Jess and I held our advantageous spot at the curb. My best friend soaked in the late morning sun, sipping her raspberry lemon mimosa, watching me stare at him.

She elbowed me. “Who’s he and why are you staring at each other? Wait—Ellie, is he…”

My eyes skipped to Jess to deliver a dirty look. When I refocused across the street, he was gone. “The guy who followed me home the other night. Yes, I think so. There’s no one else as tall. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe he’s just staying nearby.”

“And maybe you should say something to someone.”

“Not until I’m certain. Paranoia is my sister’s thing, not mine. Besides, aren’t you always saying I should be more open to meeting new people?”

“You do need to get out of your artsy little head. Just be careful.”

I struggled, trying to reconcile his presence in town and the sense that he watched me. After all, it was summertime. Stonington was a historically rich town, the only one in Connecticut to face the open Atlantic waters, so it attracted countless visitors. It was common to see strangers around town. Drunken tourists wandered the streets at night, unaware most businesses closed before ten. It was a colonial fishing town, and outsiders came from far and wide to work for the commercial fleet. It wasn’t the first time a man from one of the crews or a tourist had looked my way, I reasoned.

Then I saw him again.

The next day after the last of my noisy day-campers had gone, I locked the art studio door and headed for the fishing pier to sketch. It was either that or listen to another of Jess’s lectures. She’d go on about how I wallowed in self-imposed loneliness, and how it left her alone to test the waters in the pool of dateable men. The pool was small—blue plastic toddler swimming pool small—and I didn’t need to dip a toe to know there was nothing left in it for me.

The pier was a respite from my grandmother and sister’s intrusiveness as well. Gran and Isobel were all I had, and they meant well. Trysts with my art kept me sane, human.

I looked out over the harbor and spotted Neptune trudging her way in. The sailboats beyond paled in her presence. I don’t know what it was about the old girl, but I loved that fishing boat. Her emerald green hull had become chalky over time, and the once black and white hoists and booms were covered in rust, but she was still glorious against the backdrop of the sea. I lost myself in the sketch at once.

Photo by Laura Benedict

Dear Anonymous Author of The Last White Rose:

What a pleasure it was to critique this novel opening. There’s so much to work with here: you’ve obviously read a great deal of fiction and have a practiced hand in basic mechanics. Your grammar and sentence structure are strong, and even your barely-mentioned characters are vivid and distinctive. You also know how to structure a scene, which is no small feat, and your first person POV is flawless.

I like the Connecticut setting. It gives the story an immediate New England gothic feel. Gothic is one of my most beloved genres, so I’m particular.

Jess and Ellie have good chemistry. Jess is a lot of fun, though she falls down a bit on the best friend front. (More on that later.) These cracked me up: “My best friend soaked in the late morning sun, sipping her raspberry lemon mimosa, watching me stare at him.” And “She’d go on about how I wallowed in self-imposed loneliness, and how it left her alone to test the waters in the pool of dateable men. The pool was small—blue plastic toddler swimming pool small—and I didn’t need to dip a toe to know there was nothing left in it for me.”

And the scene with the Neptune was completely charming and nicely visualized. I could picture the boat “trudging” its way in. Your descriptions are—for the most part—very nicely done.

Please, dear Anonymous Author, read all of the above twice, because I know that, like most writers, you will forget it immediately as you read my criticisms and suggestions.

Here we go:

I’m not sure what sort of novel this is, and that distresses me. It contains gothic and demonic elements and is set in an old New England town. But there’s some romance as well. I need a few more hints. Does our heroine feel strangely attracted to the giant hot guy stalking her? Or is there some menace in the town that he might be connected to? The strong emphasis on the stalking makes me think it’s trying to be a thriller, but the stalker’s attractiveness makes me wonder if he’s a demi-god or paranormal beast or demon. Another mystery is that we don’t know if he’s the guy in the epigraph or not.

There’s a phrase that I learned from my mother-in-law very early in my marriage: “too much of a muchness.” That’s what you have in this opening section. You need to take a breath. Don’t try to tell us everything in 672 words, and definitely only tell us things once. Readers are smart. This section has too many repeated actions, too much stalking, and way too many characters. It’s important to mention or introduce all of your significant characters in the first thirty pages of a novel, but if you try to do it in the first three, your reader is going to be very confused. Fortunately, you can look at this as an embarrassment of riches because you can use much of this detail in other parts of the novel.

It’s also important for you to balance the light and dark. You can have both.

The last thing I want to address is your heroine, Ellie. Good heroines can be tough to write. Sidekicks get to be fun, villains get to be fun. Heroines can be a bit dull. Thoughts on Ellie below.

Epigraph

This is a dream: check.

I’m a bit confused as to how Ellie’s seeing her eyes in one line, then is falling to her knees in the next. Is she watching herself? Or is she experiencing it? Just clarify. Even if it’s a dream, it has to have its own dream physics and dream logic.

Perhaps reframe it so we know she is watching it as a scene, wondering at her own complicity.

“Strident” is awkward. As is “invincible blue eyes raging with white fire.” There’s an awful lot happening in those eyes all at once.

“He is ending my life.” Simple and to the point, but “ending” feels a bit tame since she’s about to be devoured/murdered by what appears to be a demon.

Clarify the last line and be specific:

“I wake, screaming, to find those same blue eyes—now watchful and worried (or laughing and scornful, etc)—gazing into mine.”

Chapter One

First paragraph:

The opening lines are confusing. He’s a ghostly elusive guy that has been skulking around the shadows for…some period of time. Months? Weeks? Two days? Then in the next sentence she gets to the immediate scene: “I saw his face for the first time…”

Instead, get right into it.

We’re prepped by the epigraph for scary and dubious. Give us something new at the top of chapter one. I’d much rather read: “The first time I saw Jeremy Porter’s* handsome face, he was smirking at me from the opposite side of Water Street.” Something straightforward adds a bit of levity, and keeps the story from being so frontloaded with ominosity (technically not a word, but ominousness is clumsy). I confess that I’ve been guilty of over-ominosity myself, so I know whereof I speak. He seems more condescending than threatening. If you want to make him threatening, change “smirking” to “staring.”

*Don’t be afraid to name the guy. We know he has a name. As Ellie’s telling the story, she already knows his name because she’s telling it in the past tense. As it is, it’s cheap suspense. If the story were all in present tense/present action, then we wouldn’t find out his name until she learns it. But the cat’s already out of the bag.

By making the opening of Chapter One just another in a series of stalking incidents, you’ve taken away the power of the epigraph, which could be very compelling. The epigraph hints that she dreams of a man who might be a demon, but she wakes to find him watching her in real life. My assumption is that she becomes romantically involved with sexy stalker guy during the course of the novel…? But we still don’t know if epigraph guy and stalker guy are the same.

The epigraph has already set your tone. Let it rest. We get it.

“He was magnificent.”

Our guy is obviously a gorgeous, eye feast of a man, and the word “magnificent” is striking. I kind of imagine him as a blond Gaston, from Beauty and the Beast. Is he unreal in his perfection? Some small flaw would make him more believable—unless you’re going for supernatural perfection.

Let’s break it down:

Why would we never find someone like him living in small-town New England? Where would we see a man like him? Hollywood? The cover of a magazine or romance novel?

Imposing height—how tall? Ellie says: “There’s no one else as tall.” What does that mean? Significantly taller than everyone else in town? Wilt Chamberlain tall? If so, someone would have surely noticed him by now. A man that tall would be a very poor skulker.

Instead of using an indefinite phrase like “defined his stature,” let’s see him through Ellie’s editorial filters:

“I’d never seen a man so tall in real life, at least not one with shoulders so broad that they made me wonder for a moment if he had to have his dress shirts specially made. But he wasn’t wearing a dress shirt. His taut, cut biceps emerged from the sleeves of a beautifully faded black tee that just reached the waist of his indigo jeans. And his black motorcycle boots looked comfortably worn. Most women I knew would pay a fortune to have their stylist give them highlights like the ones that seemed to flow naturally through the waves of his dark blond hair. His jaw was strong and commanding, reminding me of paintings I’d seen of ancient Roman centurions on my last trip to the Louvre.

“Parade’s over,” someone behind me shouted.

I startled, and felt my face flush. The slow smile of the man I came to know as Jeremy Porter told me he’d caught me staring.”

Then you can go on and have her interact with Jess. But let’s have some more urgency and concern in their exchange. Is Jess implying Ellie should call the authorities? Who is the “someone” of whom she speaks? Be specific.

In this next section, we get a lot of new characters introduced: noisy day-campers, dateable men, Gran and Isobel, an anthropomorphized fishing boat, drunken tourists, sailors. It’s overwhelming.

And, suddenly, skulking sexy guy appears again.

What is this book about? Right now I’m just reading stalking scenes, and I’m feeling fearful that they will just go on and on…

Three scenes (including the epigraph, if it is the same guy), three appearances. Actually four, because we learn he followed her home on some other night (super alarming to have a giant follow you home!). We have no resolution of his parade appearance in Chapter One before the pier scene. He has now let her see his face, and he’s still obviously stalking her. Please give Ellie some spunk. She seems incredibly unaffected by his stalking—her friend acts alarmed but then apparently lets her go home and go about her business and go to work the next day without any further investigation of the guy. It’s one thing that Ellie’s not paranoid. It’s quite another to make her seem not very bright. And I think she is bright.

Your opening chapter has to do more than establish the tone, and Chapter One tells us little more than that Ellie is living in a historic small town and is being stalked by a hot guy. It’s an ominous situation, but she’s reacting in a way that’s not credible. And we still don’t know if this is a romance, a thriller, or a paranormal story. Give us better clues.

My first suggestion would be to work on the epigraph and just let it set the tone. Then in your opening chapter, have Ellie confront hot stalker guy after the parade. It will make her the real protagonist rather than a woman who seems to be setting herself up as a victim. I love the sketching scene on the pier, but it’s too much with what you have already. Save the setting and scene—maybe it happens after they’ve actually met.

Having her confront the guy right off puts us immediately into the story, and will surprise the reader. Even if he is our villain, he will be put momentarily off-balance. Ellie and the hot guy instantly become equals, and thus more interesting adversaries. Or a more interesting couple. Therefore it becomes a more compelling story. Be bold.

That’s my two cents. I think this story could go far.

Chatter over, TKZ friends and bloggers. What say you?

This story was difficult to write, because my protagonist was so dislikeable. We learn straight out that Tiffany Yokum is a gold digger – and a calculating killer.

This story was difficult to write, because my protagonist was so dislikeable. We learn straight out that Tiffany Yokum is a gold digger – and a calculating killer. The award-winning Evan Hunter – a.k.a. Ed McBain – made that recommendation. It works if your villains aren’t too evil. McBain had a lot of sniffling and sneezing detectives in the 87th Precinct. But I could give Tiffany pneumonia – heck, Covid-19 – and she still wouldn’t be likeable.

The award-winning Evan Hunter – a.k.a. Ed McBain – made that recommendation. It works if your villains aren’t too evil. McBain had a lot of sniffling and sneezing detectives in the 87th Precinct. But I could give Tiffany pneumonia – heck, Covid-19 – and she still wouldn’t be likeable.

Tiffany quickly becomes the fourth wife of rich old Cole Osborne and they live in luxury in Fort Lauderdale.

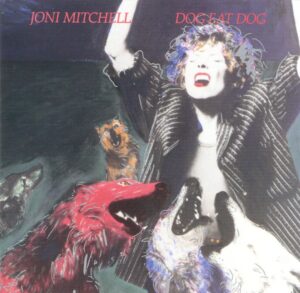

Tiffany quickly becomes the fourth wife of rich old Cole Osborne and they live in luxury in Fort Lauderdale. The Joni Mitchell song was Tiffany’s anthem, and she recognized herself in the lyrics of “Dog Eat Dog.” Especially the part about slaves. Some were well-treated . . .

The Joni Mitchell song was Tiffany’s anthem, and she recognized herself in the lyrics of “Dog Eat Dog.” Especially the part about slaves. Some were well-treated . . . Cindy knew she’s landed her pretty derriere in a tub of butter, but she knew her work has just started. Among other things, Cindy changed her name to a classier “Tish.”

Cindy knew she’s landed her pretty derriere in a tub of butter, but she knew her work has just started. Among other things, Cindy changed her name to a classier “Tish.”

Tiffany says, “I thought I could sail smoothly into Cole’s sunset years and collect the cash when he went to his reward. But then that damn preacher showed up. The smarmy Reverend Joseph Starr, mega-millionaire pastor of Starr in the Heavens.”

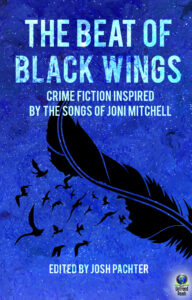

Tiffany says, “I thought I could sail smoothly into Cole’s sunset years and collect the cash when he went to his reward. But then that damn preacher showed up. The smarmy Reverend Joseph Starr, mega-millionaire pastor of Starr in the Heavens.” The Beat of Black Wings, edited by Josh Pachter, is an anthology of 28 crime writers who wrote short stories inspired by Joni Mitchell’s lyrics. The award-winning authors include Art Taylor and Tara Laskowski, Kathryn O’Sullivan, Stacy Woodson, and Donna Andrews. A third of the royalties will be donated to the Brain Aneurysm Foundation in Joni Mitchell’s name.

The Beat of Black Wings, edited by Josh Pachter, is an anthology of 28 crime writers who wrote short stories inspired by Joni Mitchell’s lyrics. The award-winning authors include Art Taylor and Tara Laskowski, Kathryn O’Sullivan, Stacy Woodson, and Donna Andrews. A third of the royalties will be donated to the Brain Aneurysm Foundation in Joni Mitchell’s name.