End of year is a time for reflection. So spill it. What advice would you give to your younger writer self…and at what age?

For an added degree of difficulty…would you listen? We’re all ears…

Today’s post is an excerpt from my new writing book, “Story Fix: Transform Your Novel From Broken to Brilliant.”

This is the eleventh chapter, out of 15 plus an Introduction, and thus it is written in context to what I believe to be the highest ambition of the book: to show you two things… the scary roster of stuff that can conspire to contribute to your novel being rejected (and how to reduce that risk)… and the inherent opportunity that awaits those who seek to understand the reasons why it was rejected.

Too often, upon hearing the dark news, writers simply find a new target and sent out another submission. As if the rejecting agent or editor has their head up their… sweater.

Maybe.

Just as often, the rejecting party – an agent or a publisher – doesn’t provide any real feedback from which the author might embark upon an upgrade, if not outright repair of the manuscript.

And thus (and herein commences the excerpt)…

Welcome to the Bermuda Triangle of Storytelling.

Your story is a vessel. It must float on a sea of possibility. If the weight of absurdity, familiarity, or underachievement is too heavy, the boat will sink. The relationship between an idea, a concept, and a premise defines the Bermuda Triangle of storytelling, where well-intentioned writers too often set sail without the right navigation, sensibility, or awareness to avoid being swallowed alive.

Surviving these deadly waters requires more than knowing how to swim (i.e., how to write nice sentences), or having an interesting idea alone. It’s knowing how to navigate the waters of a story, with a vessel that is strong and seaworthy.

After reading the chapters thus far, this is, of course, old news. But what remains floating is perhaps our willingness to embrace it all, to allow the principles to flow in as our limited beliefs are dumped overboard. That, like storytelling itself, is sometimes a hard thing to accomplish.

There’s a reason why revision is so freaking hard.

But if you think about it, it shouldn’t be. With all these principles and tools, it should at least be manageable. The damage is sitting in the rejected draft, staring back at you, mocking you, or it’s ringing in your ears from an outside source. The upside should position revision as more of a gift than a burden, but that’s sometimes hard to see, because you are either in denial, or you know it was you who did it that way in the first place, working with the best of intentions and without the slightest clue you were mismanaging the moment. So now, armed only with a new awareness, perhaps a need you don’t even understand, you’re supposed to suddenly bring something different to the process of fixing it?

This is craziness in its purest form.

If you’re a professional writer seeking representation from an agent, or to land a contract from a publisher, or even just to earn a little buzz in the crowded wilderness of self-published fiction, then one thing is beyond argument: Rejection hurts. It sucks on so many levels, even though the public writing conversation has assured you this was coming, because it always does. It still hurts.

And yet, despite the pain, and unlike so many other avocations that we embrace because they are fun and personally (versus professionally) rewarding, rejection matters. Hey, we believe we’re pretty good at the stuff we do personally: dancing, karaoke, golf, painting, poker, knitting, ping pong, bodybuilding, cooking. You can play crappy golf or tennis or bridge every weekend for the rest of your life, and it doesn’t change your experience or alter your future. You’re still having a good time. But this isn’t the case with writing. We thrive on hope, on the belief that our efforts are actually leading us toward something.

Pain exists not because it is an issue of winning or losing but rather because it is a measure of personal identity and ambition. Rejection threatens our dream. But that perception is exactly backwards. Rejection reminds us how hard this is, dashing hope in the process, and yet perhaps fueling us with an ambition that seeks to find an upside.

While you likely wouldn’t think to declare yourself a professional in your weekend recreational pursuits, as a writer, otherwise worldly and wise, you might consider yourself a professional even now. You go to writing conferences, read writing books, seek representation, and suddenly, because you absolutely do intend to sell your work, you bestow upon yourself the mantle of the professional. Which means—and here is a rarely spoken truth—you are competing with everyone else at the writing conference, if for nothing else than mindshare and respect from agents and editors. The respect and props you seek from them are defined by how your story compares to everyone else’s.

But you opted in as a professional, not a weekend warrior. Which means you don’t get to take it personally. For the enlightened professional, the call for revision becomes an opportunity rather than a reminder of your limitations.

And yet, it seems so … daunting.

What you hear at the writing conference, particularly when it comes to the revision process, may not take you where you want to go. Not because the advice you pick up is wrong, per se, but because it can be imprecise. It comes at you in pieces, little chunks of conventional wisdom floating alone and unconnected—as from a workshop on how to write better dialogue, for example—on a sea of assumed yet less-than-clear relevance to a bigger picture.

So you’re saying better dialogue will make my novel better? The answer is: Sure it will. Always. But then there’s this slightly different question: So you’re saying that writing better dialogue will get me published?

This is why many writers drink.

And why writing teachers exist at the very edge of madness.

The bigger picture will save you.

When your story requires revision, chances are something you’ve done doesn’t fully align with the principles that show us how a story works, and it can be found at the story level rather than the craft level.

The sow’s ear, chicken-droppings level.

Listen closely … that sound in your head may be your inner author trying to tell you something. And chances are you really need to hear it.

The more you know about the craft of storytelling, the louder that voice becomes. The more you know about storytelling—both at the story level and the craft level—the clearer the message itself will be. Our profession is full of writers who hear the call. They acknowledge doubt in the form of that inner voice telling them something is off the mark, but they don’t really know how to respond. Usually they respond by submitting it somewhere else to see what happens, hoping to confirm their suspicion that the first agent or editor was having a bad day.

And then it comes back to you with the same outcome. And the voice telling you to revise becomes louder and more impatient.

The enlightened writer listens.

You’ve been introduced to the tools, criteria, and benchmarks of a strong story that can be applied to the revision process, as well as to a first draft. Maybe you haven’t yet internalized them. Maybe you zoned out when they were being presented at the writing conference. Maybe you opted for the session on how to land an agent instead. Maybe you prefer the indulgent musings of keynote speakers who wax eloquent about the mystery of it all, the muse that channels through them, the characters that speak to them, the immersion in their process with the trust that somehow, some way, someday, their story will finally make sense.

Here’s a newsflash for those writers who like to tell their friends that there is something mystical in what we do: There are no actual muses (there are inspirations, which are different animals), and your characters don’t talk to you. When stories are broken—they are very much like friends and relatives and politicians in this regard—they’re not going to confess to their sins and give you a strategy for healing. No, the voices you ascribe to muses and talking characters are you, speaking to yourself from a place of story sensibility, which for better or worse is the sum and nuance of all that you’ve read and studied and learned and concluded on your writing journey.

You’ll finally hear it—it’ll sound a lot like an improved sense of story when you do—because it makes sense to you. Because you’ve had your fill of pain and frustration, and you’re finally opening up to higher thinking.

Seeking the Sweet Spot

I offer this next point from my experience presenting writing workshops for the last twenty-five years. Writers arrive in the room with certain belief systems about writing that defines what is and isn’t true in their minds. This causes them to be resistant to anything that challenges those beliefs and leads to a rather strong sense of confidence that what they’ve written, or intend to write, is rock solid and infused with genius. When something challenges that assumption—like someone saying that your characters don’t talk to you, or that there may be a better path for your story—they shut down to some extent. They are processing the contradictions, the perception of falsehood hanging in the air, and thus don’t completely perceive the meaning and inherent opportunity in what’s being presented.

Some readers of this book will, at this point, not clearly comprehend a critical nuance: that the process of story fixing isn’t just for rejected books, it’s for any story that seeks to become a better story. And complicating this is the cold, hard truth that some rejected books aren’t necessarily broken at all; they simply may not have landed in the sweet spot, at the right time, of their publishing journey. In this sense, revision is merely a form of starting over, building your best story from the inside out, from the ground up, from the truth of the principles that will never steer you wrong.

To Revise Or Not To Revise

Then again, every rejection slip does not necessarily signal the need for a major revision. Your story may be perfectly fine as is. The rejection may come from a source you do not understand, and therefore do not value. More often, though, harsh criticism and rejection may actually be the wake-up call the writer needs. And thus, it’s on the shoulders of the writer to know the difference—timing rather than a lack of sufficient craft—and to use feedback in all its forms to accurately assess the story’s strengths and weaknesses and apply that feedback to move forward accordingly. The tools and processes apply to any origin of the need for story repair, however it is conveyed—be it a rejection or simply a depressing hunch that won’t leave you alone.

Worthy stories, some of which go on to success, certainly do get rejected all the time, both by agents and publishers. These are the stuff of urban legend. Do a quick Google search and you’ll find them everywhere. I’ll mention again the quote from esteemed author William Goldman: “Nobody knows anything.”

It’s too true. But it’s also a risky way to place your bet. Because you could rationalize the rejection of your story as simply a case of timing or another agent who doesn’t get it rather than a legitimate red flag that should get your attention. We can be sure that Kathryn Stockett didn’t revise her manuscript forty-six times, one for each instance of rejection. But because she hasn’t talked about it, we can’t say for sure how those rejections colored her subsequent sequence of drafts, if at all.

Right here is where a paradox kicks in: If you don’t possess the knowledge to nail it the first time out, and are now stuck with the need to revise, how can you leverage feedback and rejection in the writing of a subsequent draft to solve those problems? You’re the same writer who wrote that flawed story. How can you suddenly, without elevating your skill set, attempt to hoist good toward greatness? That’s like asking a toddler who has just fallen off his bicycle to simply get back up and try it again, without showing him what went wrong. A lot of fathers have tried just that method over the years—“It builds character,” they say—and it’s always a recipe for further frustration and tears, as well as a few Band-Aids.

You can’t expect to take your story higher with the same skill set as before, at least to the extent that you don’t understand the feedback itself. But you’re here, you’re learning the unique tools and principles that drive successful revision, and that just might change everything about your next swing at the story.

As professional writers we are beyond the need to use our work as a means of personal character building. We require knowledge applied toward the growth of something much more amorphous and elusive: a heightened storytelling sense.

“Writing the novel is half the battle. The other half is fixing it. In this book, master craftsman Larry Brooks gives you his set of tools for the fix-it stage. So strap on your belt, and get to work!” — James Scott Bell, author of Write Great Fiction: Plot & Structure

It’s my pleasure to introduce someone I’ve known for a long time, an Okie friend. I first knew Ken Raymond of The Oklahoman newspaper as a crime beat and features reporter. He is a talented author as well. After he graced me with a glimpse of his work, I’ve been trying to coerce him to write a novel ever since and hope he does one day. Very talented guy. Now he’s the book review editor at the paper, a man of many hats. Please chat Ken up, TKZers.

P S – I will be traveling and in remote spots this week. I may not have access to the internet, but I will try to check in on post day.

Ken Raymond’s Post:

Last year I interviewed David Sedaris, the humorist renowned for essays such as “Santaland Diaries,” a hilarious chronicle of his days working as an elf at Macy’s one holiday season.

We didn’t have much in common, aside from our mutual appreciation of his work, but we both love books … and we share a similar problem.

Whenever Sedaris makes a public appearance, would-be authors thrust their manuscripts at him. He’s not sure why, but he thinks they hope he will read all the books, pass them on to his editors and launch the writers’ book careers.That never happens. Sometimes he says no to the manuscripts; other times he takes them out of a sense of politeness and civility.

Even if he wanted, he could never find time to read them all.

I’m not famous. I don’t make many public appearances, and when I do, they’re usually at writing conferences or classrooms. But I do get buried in books, most of them unsolicited. Dozens pile up outside my front door each week, and more still find their way to what used to be my office.

Who am I? I’m just the book editor for The Oklahoman newspaper in Oklahoma City. Book editor sounds important, but really I’m just one guy who reads and reviews books and tries to convince other people to do the same. My staff, such as it is, consists of volunteer newsroom staffers and a handful of stringers, whose only recompense is a byline and a free book. I interview authors, write about industry trends and work hard to deliver the best possible product, but I’m also a columnist and senior feature writer. There are only so many hours in the day.

Don’t get me wrong: I love my job. I’m among the fortunate few in this world who are paid to read books. The problem is that there are just so many of them, good and bad, in all genres and styles.

Given all that competition, how can you make your book stand out — to me and to the countless other reviewers out there?

There’s no guarantee of success, but these tips may help:

Be honest.

For some reason, no one wants to come across as a beginner in the writing business. I guess everyone assumes that if they’re not all polished and shiny, they won’t stand out.

Me, I’m sick of flashy. I get hundreds of emails a week from authors or publicists, and sometimes from authors pretending to be publicists. The messages are so flashy they look like old Geocities websites, with weasel words thrown in to make it seem as if the books they’re pitching are the biggest thing to hit literature since the Gutenberg Bible. Read them closely, though, and they’re largely unappealing campaigns of self-aggrandizement.

I prefer a simpler approach: the truth. Don’t try to impress me; your book should do that. Your emails should tell me who you are, what you’ve written and why you think it stands out. Talk to me like we’re eating lunch together, and I’ll listen.

I’ll also tell you what I tell everyone these days. I can never promise coverage, but I’ll give you the same chance at a review that every other author gets, including the famous ones. I’ll look at your book, and if it’s not for me, then I’ll offer it up to my review team. If anyone picks it and thinks it’s pretty good, I’ll run a review. If they don’t like it, I probably won’t run a review.

Follow up.

If you apply for a job, odds are you won’t sit by the phone for two weeks, hoping it’ll ring. Instead, you’ll follow up a few days after the interview, letting the company know you’re interested and making sure you’re remembered. You may follow up again a week later.

The same goes for book promotion. Often someone will pitch a book to me, and I’ll ask for a review copy. By the time the book arrives in the mail, I may not remember it at all; I’ve dealt with a bunch of other books in the interval.

A simple follow-up email reminds me that we communicated about the book. It tells me that I was interested enough to request it. It’ll make me take a closer look.

Don’t take it personally.

Nothing turns me against a book more than an argumentative author. Earlier this year, a guy blitzed me with phone calls and emails, demanding that I review his minor book about his favorite subject: himself.

Somehow he had browbeaten other news organizations into writing reviews, none of which were particularly flattering. When his berserk behavior persisted, I told him I wasn’t interested in interviewing him or reading his book. He promptly called my boss eight times in a two-hour period and drowned him in email.

He seemed shocked, absolutely shocked, that he couldn’t force his way into the paper.

I don’t want to be a puppet. Most people don’t seek out needless confrontation. If we all act professionally, we should get along fine, even if I can’t get to your book or publish a review. I bear you no ill will; without you, I couldn’t do my job.

Play the odds.

Major publishers release fewer books during the cold weather months. The spring, summer and fall are all pretty hectic, so those winter months are your best opportunity to contact me. You simply won’t have as much competition.

At the same time, I scramble for content around that time of year. I suspect others in my position do, too. I start pushing gift books on Black Friday and continue every week until Christmas. Even if your book came out much earlier in the year, I may use it in one of my gift guides. I generally offer a range of books in different genres.

But winter isn’t your only window. Whenever possible, people like me prefer to publish reviews proximate in time to book release dates. If I could, I would limit most of my reviews to books that are about to come out in a couple days.

In order for that to happen, I need your book about a month in advance. Some critics prefer digital copies; I like physical books, even if they’re uncorrected page proofs.

Because I am in Oklahoma, I take special interest in books with some sort of Oklahoma ties. If you live here, went to college here, set your book here, whatever, that’ll up your odds of getting reviewed. The same applies to other regional newspapers. If you’re in Alaska, pitch your book hard to Alaskan publications.

Set up book signings, too. You probably won’t get rich at a book signing, since stores take part of the haul, but I always mention local book signings in print. Many other papers do the same. It may not be as good as a full review, but at least it gets your name out there.

Best of luck, and please contact me about your upcoming books. The best way to reach me is via email at kraymond@oklahoman.com. Follow me on Twitter at @kosar1969.

Discussion: Any questions for a book review editor, TKZers? You ever wonder what a crime beat reporter sees on the job? Or maybe you want to know what was the strangest features article Ken ever wrote? Ask away!

Bio:

Ken Raymond is the book editor and a senior writer at The Oklahoman. He publishes a monthly column called “Purely Subjective.” A Fulbright scholar and Pennsylvania native, he covered crime for much of his career, bringing dramatic stories to life through literary nonfiction. He has won numerous national, regional and state awards. Three times he has been named Oklahoma’s best writer by the Society of Professional Journalists. He lives in Edmond with his wife, three Italian greyhounds and a Chihuahua.

“A great book should leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading.” — William Styron

By PJ Parrish

We moved around a lot when I was a kid, and like a plant with shallow roots, I was always sending out feelers toward solid ground. I found it in libraries. I couldn’t always count on having the same address every year, the same classroom or even the same friends for very long. But I always could count on finding old faces and familiar places in the local library.

Paradoxically, it was in libraries where my love of exotic places and travel was born. No matter what was going on in my little life, I could escape to somewhere else by opening a book. My library card was my first passport.

Novels took me around the world, but they also taught me things — about history, religion, politics, philosophy, human psychology, medicine, outer space – filling in the gaps left by my spotty education. Even after I went to college, made my own money and settled down, novels remained my autodidact keys.

I learned about the American Revolution through John Jake’s Kent Family Chronicles. I studied medieval Japan through James Clavell’s Shogun. I was able to wrap my brain around the complex politics of Israel and Ireland after reading Leon Uris. James Michener taught me about Hawaii and Edna Ferber took me to Texas. Susan Howatch’s Starbridge series sorted out the Church of England for me. Ayn Rand made me want to be an architect for a while, or maybe a lady reporter who wore good suits. (I skimmed over the political stuff.)

And Arthur Hailey taught me to never buy a car that was made on a Monday.

I got to thinking about Hailey and all the others this week for two reasons: First, was an article I read in the New York Times about the Common Core teaching controversy (more on that later). The second reason was that while pruning my bookshelves, I found an old copy of The Moneychangers. This was one of Hailey’s last books, written after he had become famous for Hotel, Wheels, and that quintessential airport book Airport. I interviewed Hailey in 1975 when he was touring for The Moneychangers. I remember him as sweet and patient with a cub reporter and he signed my book “To Kristy Montee, Memento of a Pleasant Meeting.”

I had read all his other books, especially devouring Wheels, which was set in the auto industry of my Detroit hometown. Hailey, like Michener, Clavell, Uris et al, wrote long, research-dense novels that moved huge, often multi-generation casts of characters across sprawling stages of exotic locales (Yes, Texas qualifies). Hawaii, which spans hundreds of years, starts with this primordial belch:

Millions upon millions of years ago, when the continents were already formed and the principle features of the earth had been decided, there existed, then as now, one aspect of the world that dwarfed all others.

How could you not read on after that? But the main reason I loved these books was for their bright promise of cracking open the door on something secret. Here’s some cover copy from Hailey’s The Moneychangers:

Money. People. Banking. This fast-paced, exciting novel is the “inside” story of all three. As timely as today’s headlines, as revealing as a full-scale investigation.

Shoot, that could be copy written for Joseph Finder now.

Many of these books were sniffed off as potboilers in their day. (Though Michener and Ferber both won Pulitzer Prizes). But the writers were, to a one, known for their meticulous research techniques. Hailey spent a full year researching his subject (he read 27 books about the hotel industry), then six months reviewing his notes and, finally, about 18 months writing the book. Michener lived in each of his locales, read and interviewed voraciously, and collected documents, music, photographs, maps, recipes, and notebooks filled with facts. He would paste pages from the small notebooks, along with clippings, photos and other things he had collected into larger notebooks. Sort of an early version of Scrivener.

For my money, these books were a potent blend of entertainment and information, and they endure today as solid examples for novelists on how to marry research with storytelling. In his fascinating non-fiction book Hit Lit: Cracking the Code of the Twentieth Century’s Biggest Bestsellers, James W. Hall analyzes what commonalities can be found in mega-selling books. One of the criteria is large doses of information that make readers believe they are getting the inside scoop, especially of a “secret” society. The Firm peeks into the boardrooms of Harvard lawyers. The Da Vinci Code draws back the curtain on the Catholic Church. Those and all the books I cited delivered one thing in spades — the feeling we are learning something while being entertained.

Which brings me to Common Core.

This is an educational initiative, sponsored by the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers that details what K–12 students should know in English language arts and mathematics at the end of each grade. I read this week that as part of the Common Core mandate, English teachers must balance each novel they teach with “fact” material –news articles, textbooks, documentaries, maps and such.

So ninth graders reading The Odyssey must also read the G.I. Bill of Rights. Eight graders reading Tom Sawyer also get an op-ed article on teen unemployment. The standards stipulate that in elementary and middle school, at least half of what English students read must be supplemental non-fiction, and by 12th grade, that goes up to 70 percent.

Now, I’m not going to dig into the politics of this. (You can read the Times article here.) And I applaud anything that gets kids reading at all. What concerns me is that in an effort to stuff as much information and facts into kids’ heads, we might not be leaving room for the imagination to roam free. As one mom (whose fifth-grade son came home in tears after having to read the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), put it, “If you look at the standards and what they say, nowhere in there does it say, ‘kill the love of reading.’”

One more thing, I then I’ll shut up:

There was a study done at Emory University last year that looked at what happens to the brain when you read a novel. At night, volunteers read 30-page segments of Robert Harris’s novel Pompeii then the next morning got MRIs. After 19 days of finishing the novel and morning MRIs, the results revealed that reading the novel heightened connectivity in the left temporal cortex, the area of the brain associated with receptivity for language. Reading the novel also heightened connectivity in “embodied semantics,” which means the readers thought about the action they were reading about. For example, thinking about swimming can trigger the some of the same neural connections as physical swimming.

“The neural changes that we found…suggest that reading a novel can transport you into the body of the protagonist,” said Gregory Berns, the lead author of the study. “We already knew that good stories can put you in someone else’s shoes in a figurative sense. Now we’re seeing that something may also be happening biologically.”

Maybe those poor eighth graders just need to crack open some Jean Auel, SE Hinton or Cassandra Clare.

(Image courtesy of Gualberto107 at FreeDigitalPhotos.net)

I never really paid much attention to birds until I met and married my wife Lisa. She is — and there is no other way to put it — obsessed with birds. We have hard drives figuratively bursting at the seams (and backed up, of course) with photographs of grackles, canaries, yellow whatever’s, and red these or those. While I have been observing her interest, and the subject of same, the area in which we live has experienced a marked increase in the presence of hawks. The reason doesn’t take an understanding of the nuts and bolts of nuclear propulsion to understand. We have what I will politely call more than our fair share of Canadian geese in our locale (which is not, I hasten to add, in Canada). The eggs of Canadian geese are considered by hawks to be a delicacy, in the same way that I regard the presence of a Tim Horton’s, Sonic, IHOP, or Cracker Barrel. The attitude of a hawk toward a goose egg could best be summed up by the statement, “If you lay it, I will come.” Or something like that.

Hawks will of course eat other things as well, and I’ve had opportunity to see them in the act of catch-and-not-release prey on a number of occasions. What they do is fairly highly evolved. If they catch a ground animal, they immediately take it into the air, where it is helpless and cannot run away. If they catch a bird, they bring it to ground, where it is at a disadvantage, and pin it so that it cannot fly away, while they kill it. One could say that a hawk is at a disadvantage on the ground, but I haven’t noticed squirrels, chipmunks, cats, or even other birds coming to the aid of one of their fellow and less fortunate creatures as the hawk goes about its business. No, things get really quiet for a while as the hawk exploits the weakness of its dinner.

Successful genre fiction utilizes the exploitation of strengths and weakness to succeed as well. This is particularly true when the author takes a personality trait that might, and indeed would, be considered a virtue and exploits it. We have a real world model for that, as well. Think of Ted Bundy. Those of us who are raised to be kind and polite and to assist others in need instinctively hold a door for the elderly or the infirm or pull down a top shelf grocery item for someone in a wheelchair. Bundy knew this and would wear a cast or walk on crutches while carrying a package to attract unsuspecting women. There’s a word for that: monster. But he was very, very good at it, and turned a virtue into a fatal weakness. Those who prey on children frequently do so with the premise of seeking assistance with locating a lost dog. What could be more heartwarming than reuniting a dog lover with his pet? Children are inclined to help, especially when it comes to dogs and such, and it’s a virtue that a parent would want to cultivate, but also to curb.

In the world of fiction, however, exploiting weaknesses of this type makes for a great story, and not just for mysteries or thrillers, either. Many science fiction novels and stories sprung from a seed of an advanced civilization bringing advancement to a primitive, or weaker, one with the best of intentions. Disaster inevitably ensued, for one side, or the other, or both. James Tiptree, Jr., was a master of this type of situation, as was the original Star Trek series. Romance novels? Think of a woman who is physically attractive to the extent that no one will approach her, out of fear of rejection. That idea has launched a thousand books and will undoubtedly launch a thousand more before this sentence is completed. As for mysteries and thrillers, the possibilities are endless and replicable: think of a strength, or a virtue, and find a weak spot to exploit. Create an antagonist to probe it and you’re on your way.

Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley comes to my mind most immediately as someone who was excellent at exploiting the best of others. Who comes to yours?

And…I would be remiss if I did not wish a Happy Mother’s Day tomorrow to those among our readers who celebrate the event . Bless you. You are the best.

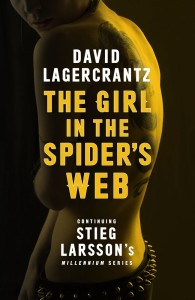

I regret to inform you that I am eternally behind the curve. My seventeen year old daughter would happily reveal that state of affairs, and does so at every opportunity (notwithstanding that it was I who first told her about Leon Bridges). So it is that it was only yesterday when I learned that this coming September 1 we’ll be seeing The Girl in the Spider’s Web, a fourth installment in the Lisbeth Salander canon (also known as The Millennium Trilogy) which began with the now world-famous The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson. The new volume will be written by David Lagercrantz, who has been retained to write it by Larsson’s estate, which consists of Larsson’s father and brother. And therein lays the rub.

I regret to inform you that I am eternally behind the curve. My seventeen year old daughter would happily reveal that state of affairs, and does so at every opportunity (notwithstanding that it was I who first told her about Leon Bridges). So it is that it was only yesterday when I learned that this coming September 1 we’ll be seeing The Girl in the Spider’s Web, a fourth installment in the Lisbeth Salander canon (also known as The Millennium Trilogy) which began with the now world-famous The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson. The new volume will be written by David Lagercrantz, who has been retained to write it by Larsson’s estate, which consists of Larsson’s father and brother. And therein lays the rub.

The lead up to the publication of the Salander books has been covered exhaustively elsewhere and can be had with Google search. For our purposes today we’ll touch only on the high (or low) points. Larsson conceived the Salander canon as consisting of ten books. He wrote three, substantially completed a fourth, and outlined volumes five through ten. Larsson died of a heart attack in 2004, however, before any of the books were published. A will which Larsson drafted in 1977 was discovered after his death, but his signature had been unwitnessed. The will was thus declared invalid under Swedish law. Worse, Larsson’s longtime companion, Eva Gabrielsson, could not inherit from him under intestate succession, which is the order in which relatives can inherit from someone who dies without a will. Larsson’s intellectual property — the Salander books — thus passed to his father and brother, who were his nearest living relatives but from whom, by most accounts, he had been estranged for many years.

Many of us — me included — believe that we are going to live forever, or at least at a point far enough in the future where it won’t make any difference, and don’t have a will as a result. While Larsson went through the motions, he didn’t go through enough of them. It is doubtful that Larsson contemplated the possibility that he would be toasting marshmallows with Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky about the time that The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo was hitting the top of the bestseller charts all over the world. The result is that Larsson’s closest blood relatives received his entire kit and caboodle. Ms. Gabrielsson, with whom Larsson shared home and hearth, and who may well have contributed substantially to the creation and expression of Larsson’s work, will never receive so much as a krona of royalties, or have any say as to how her partner’s property is handled going forward. That is now up to Dad and Bro. If you were hoping that one day your child might go to school with a Lisbeth Salander lunchbox, or you were planning to obtain a removable dragon tattoo to spice things up on some weekend, don’t lose hope. It still could happen.

Many of us — me included — believe that we are going to live forever, or at least at a point far enough in the future where it won’t make any difference, and don’t have a will as a result. While Larsson went through the motions, he didn’t go through enough of them. It is doubtful that Larsson contemplated the possibility that he would be toasting marshmallows with Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky about the time that The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo was hitting the top of the bestseller charts all over the world. The result is that Larsson’s closest blood relatives received his entire kit and caboodle. Ms. Gabrielsson, with whom Larsson shared home and hearth, and who may well have contributed substantially to the creation and expression of Larsson’s work, will never receive so much as a krona of royalties, or have any say as to how her partner’s property is handled going forward. That is now up to Dad and Bro. If you were hoping that one day your child might go to school with a Lisbeth Salander lunchbox, or you were planning to obtain a removable dragon tattoo to spice things up on some weekend, don’t lose hope. It still could happen.

Don’t let this happen to you. If you have created a piece — or several pieces — of intellectual property, be they published, recorded, or otherwise, have a will drafted in which a specific bequest of that property — and everything else you have — is made. Spend the money and go to an attorney who specializes in such matters; your attorney will/should make sure that your will is executed properly and in accordance with the laws of your state. Please believe me: this is much better than writing it out on a cocktail napkin on the third night of Bouchercon. Insist that your will explicitly states 1) to whom you are giving, or bequeathing, the specific intellectual property and 2) that you are granting to your beneficiary full administrative rights over the property. Should there be something that you do not want done with the property (such as action figures or computer game licensing) this would be the time to mention as well: put your restrictions in writing. If while bestowing your property you exclude someone who would otherwise be the natural object of your bounty, state why you are making the choices you are making. Yes, you might hurt someone’s feelings. If, however, you state that you are leaving your intellectual property to your brother because you feel that your brother is better able to deal with business matters, contesting your will successfully will be problematic for your sister.

You laugh. But you never know. There are any number of authors who didn’t live to see, and thus enjoy, their success. Do you really want someone you don’t even like deciding how your work will be treated, or — even worse — a government official choosing who will control things? The answer of course is “no.” Don’t let your loved one, whoever they may be, end up like Eva Gabrielsson.

Yesterday, Joe Moore had an excellent post “Tips for Pacing Your Novel.” It made me think of subplots and story arcs that are other tools to punch up a story line with pace while the main plot enjoys a much needed rest for character development.

In a story arc, whether it is the arc of a romantic relationship or the personal journey of your main character, it might help you think of the arc using these key points:

5 Key Movements in a Story Arc:

1. Present State

2. Something Happens

3. Stakes Escalate

4. Moment of Truth

5. Resolve

Present State – Set the stage with the character or the relationship at the start of the story. This can also include a teaser of the conflict ahead or the characters’ problems that will be tested. If this is a thriller with a faster pace, you can start with a scene that I call a Defining Scene, where you show the reader who your character is in one defining moment of introduction. The reader can see who this character is by what he or she does in that enticing opener. Don’t tell the reader by the character’s introspection (internal monologue). Set the stage by his or her actions. These scenes take thought to pull together but they are worth it. Imagine how Capt. Jack Sparrow of Pirates of the Caribbean first steps onto the big screen. He wouldn’t simply walk on and deliver a line. He’d make a splash that would give insight into who he is and will be.

Something Happens – An instigating incident forces a change in direction and a point of no return. Your character and/or relationship often will move into uncharted territory that will test their resolve. Sometimes you can set up a series of nudges for the character to reject, but in the end, something must happen to shove him or her over the edge and into the main plot.

Stakes Escalate – in a series of events, test the characters’ problem or the relationship in a way that forces a conflict where a tough choice must be made. Make your character/couple earn the right to play a starring role in your novel. Don’t forget that this is not simply the main action of the plot or a conflict with the bad guys. This can also mean escalating the stakes of the relationship by forcing them into uncomfortable territory.

Moment of Truth – When push comes to shove, give your character or couple a moment of truth. Do they choose redemption or stay the course of their lives? When the stakes are the highest, what will your character do? I often think of this moment as a type of “death.” The character must decide whether to let the past die or a part of their nature die in order to move on. Do they do what’s safe or do they take a leap into something new?

Resolve – Conclude the journey or foreshadow what the future holds to bring the story full circle. I love it when there is a sense of a character coming through a long dark tunnel where they step into the light. A character or couple don’t have to be the same or restored in the end. Make the journey realistic. If a character survives, they are more than likely changed forever. What would than mean for your character? How will they be changed?

Apply this arc structure to individual characters or to a romantic love interest between two characters. These arcs are woven into the tapestry of your overall plot. The plot can be full of action and have its own arc, but don’t forget to add depth and layering to your story by making the characters have their own personal journeys.

Characters have external plot involvements (ie the action of the story), but they can also have their internal conflicts that often make the story more memorable. As an example of this, in the Die Hard movies, we may forget the similar plots to the individual movies, but what make the films more memorable is the personal stories of John McClain and his family. These personal arcs are important and need a structured journey through the story line. They can ebb and flow to affect pace. Escalate a personal relationship during a time when the main plot is slowing down. Make readers turn the pages because they care what happens to your characters.

For Discussion:

Share your current WIP, TKZers. How do you integrate your main character’s personal journey into the overall plot? Share a bit of your character and how his or her “issues” play into your story line.

When your first book was published, was the experience everything you dreamed it would be? For me, it was quite different than what I expected. In 2005, when I first walked into a national chain bookstore and saw my brand new novel on the new release table, it was a  rush. I was proud. I felt like I was on top of the world. I couldn’t wait to see customers gather it up in their arms and rush home to read it. Then I stood back and watched as shoppers picked up my book, glanced at the back cover copy, and put it down with no more interest than in choosing one banana over another at the supermarket.

rush. I was proud. I felt like I was on top of the world. I couldn’t wait to see customers gather it up in their arms and rush home to read it. Then I stood back and watched as shoppers picked up my book, glanced at the back cover copy, and put it down with no more interest than in choosing one banana over another at the supermarket.

Didn’t they realize that book cost me 3 years of my life? How could they pass judgment on it within 5 seconds?

Reality set in. Not everyone will want to read my book. Not everyone will like it if they do read it. And I found out rather fast that once a book is published, the real work begins.

Today, I’m about to start (with co-author, Lynn Sholes) my eighth novel. My books have won awards, become bestsellers, and been published in many languages. And yet, every day I face the reality that the true test of my success or failure is what the customer does when they stand over that literary produce bin and pick what they think is the ripest banana. It’s about as scary as it can get.

As a full-time writer, I have the best job in the world. I would not trade it for anything. But a word to anyone dreaming of publishing their first book: be careful what you wish for. You just might get it.

So when your first book came out, was it everything you dreamed of? And if you’re still working at getting that first banana out there, what are you dreaming it will be like?

————–

Coming this spring: THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

Einstein got it wrong!

By Joe Moore

Okay, it’s really a 7-letter word. But I know a lot of successful authors that would use a 4-letter word when asked what it’s like to be successful. Why? For a couple of reasons. First, success is impossible to obtain. You can obtain “better”. You can achieve “improved”. But you’re always working to be successful. Success can be nothing more than a carrot on a stick just beyond your nose.

Second, success means something different to everyone. It’s a lot like describing an object as being green. Are we talking forest green, lime green, Irish green, puck green, or foam green? How about that green on the Beatles Apple logo or Kermit the Frog green?

I’ll bet if you asked any author who just sold a million copies of his last book, did it make him feel good? The answer will probably be, “Absolutely!” Does he consider himself a success? 4-letter-word no! Why? Because now his publisher expects him to sell 2 million copies of that next book he hasn’t finished writing yet. No pressure there. That’s not success. That’s a problem, albeit one we would all like to have. Now his sales are a bold number on the publisher’s ledger sheet. Now employees’ jobs rely on his success. It’s not just good enough to write another great book that sells lots of copies, he has to worry about the folks that are counting on him for their salary, their jobs, and their future.

So what is success in the publishing industry? Is it when you sell 25,000 copies, 50,000 copies, a million, become a New York Times bestseller? When can a writer kick up his or her heels and declare, “Mission Accomplished”?

Here’s a tip. Success is what you predetermine it will be. It’s what you decide before it comes. If you don’t approach success in that way, you are destined for disappointment. For some, being successful is walking into a bookstore and seeing their novel on the shelf. For other’s it’s the rush of holding a book signing and seeing the line of fans snaking out the door. And for many, it’s money.

But even if it is money, try to remember that it’s more important to predetermine what you’ll do with it, rather than wanting to be “rich”. For instance, determine the amount you’ll need to quite your day job. Or to pay off your mortgage. Or to move to Cape Cod or Palm Beach, or just a bigger house.

The point is, you determine what will make you successful. Be specific, not vague. And if you achieve it, relish it, celebrate it. Because everything after that is the sauce on the steak. And if you do achieve your predetermined success, always say the two most powerful words in the English language: Thank You.

When do you consider a writer to be a success? Have you predetermined your Mission Accomplished criteria? Have you already achieved it?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coming up Sunday, June 7, our guest blogger will be New York Times bestselling author Sandra Brown. And watch for Sunday guest blogs from Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, Julie Kramer, Grant Blackwood, and more.

By Joe Moore

A topic I’ve mentioned here in the past is Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 rules of writing fiction. They’re worth reviewing and taking to heart. But his rule number 5 is the one that made the biggest impression on me. Rule number 5 is: Start your story as close to the end as possible. This is relevant for both the entire book or a single chapter. We often hear that the most common mistake of a new writer is starting the story in the wrong place.

Well, it happens to published writers, too. Lynn Sholes and I are guilty of writing whole chapters that either occurred in the wrong place, or worse, weren’t even needed. Usually they turn out to be backstory information for us, not the reader. We go to the trouble of writing a chapter only to find it’s to confirm what we need to know, not what the reader needs to know.

So if we apply Vonnegut’s rule number 5, how do we know if we’ve started close enough to the end? Easy: we must know the destination before we begin the journey. We must know the ending first. To me, this is critical. How can we get there if we don’t know where we’re going? And once we know how our story will end, we can then apply what I call my top of the mountain technique. In my former career in the television postproduction industry, it’s called backtiming—starting at the place where something ends and working your way to the place where you want it to begin.

But before I explain top of the mountain, let’s look at the bottom of the mountain approach—the way most stories are written. You stand at the foot of an imposing mountain (the task of writing your next 100K-word novel), look up at the huge mass of what you are going to be faced with over the next 12 or so months, and wonder what it will take to get to the top (or end).

But before I explain top of the mountain, let’s look at the bottom of the mountain approach—the way most stories are written. You stand at the foot of an imposing mountain (the task of writing your next 100K-word novel), look up at the huge mass of what you are going to be faced with over the next 12 or so months, and wonder what it will take to get to the top (or end).

You start climbing, get tired, fall back, take a side trip, climb some more, hope inspiration strikes, get distracted, curse, fight fatigue, take the wrong route, fall again, paint yourself into a corner—and if you’re lucky, finally make it to the top. This method will work, but it’s a tough, painful way to go.

Now, let’s discuss the top of the mountain technique. As you begin to plan your book, even before you start your first draft, Imagine that you’re standing on  the mountain peak looking out over a grand, breathtaking view feeling invigorated, strong, and fulfilled. Imagine that the journey is over, your book is done. Look down the side of the mountain at the massive task you have just accomplished and ask yourself what series of events took place to get you to the top? Start with the last event, make a general note as to how you envision it. Then imagine what the second to the last event was that led up to the end, then the third from the last . . . you get the idea. It’s sort of like outlining in reverse.

the mountain peak looking out over a grand, breathtaking view feeling invigorated, strong, and fulfilled. Imagine that the journey is over, your book is done. Look down the side of the mountain at the massive task you have just accomplished and ask yourself what series of events took place to get you to the top? Start with the last event, make a general note as to how you envision it. Then imagine what the second to the last event was that led up to the end, then the third from the last . . . you get the idea. It’s sort of like outlining in reverse.

This takes it a step further than Vonnegut’s rule number 5 by starting at the end and working your way to the beginning while you’re still in the planning stage. Guess what happens? By the time you are actually at the beginning, you will have started as close to the end as possible. And you will see the logic and benefit of rule number 5.

Naturally, your plan can and probably will change. Your ending will get tweaked and reshaped as you approach it for real. But wouldn’t it be great to have a general destination in mind even from the first word on page one of your first draft?

Do you know your ending before you start writing? Or do you have a general idea for the story and just wing it? Remember that there’s no right or wrong answer here. But what works for you?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Coming up on our Kill Zone Guest Sundays, watch for blogs from Sandra Brown, Steve Berry, Robert Liparulo, Alexandra Sokoloff, Thomas B. Sawyer, Paul Kemprecos, Linda Fairstein, and more.