A friend told me a millennial at work couldn’t understand the clock on the wall. I’ve heard many stories involving rotary phones and cursive writing, but the clock surprised me.

A friend told me a millennial at work couldn’t understand the clock on the wall. I’ve heard many stories involving rotary phones and cursive writing, but the clock surprised me.

Even after GenXers explained the hour and minute hand, the young man still couldn’t tell time.

Made me wonder how physicians and specialists would change the screening test for cognitive deficits, particularly in neurological disorders and dementia.

If the patient doesn’t understand an analog clock, never mind be able to draw one, what object could providers substitute for the Clock Drawing Test (CDT)? Or would the CDT become obsolete?

Generational Differences

Generational differences crack me up, but I probably wouldn’t have researched Gen Z slang if I hadn’t been the recipient of a millennial rant about her dating woes — and felt about 100 years old by the end of our conversation.

All generations have their own slang. Back in the day, GenXers used wicked, awesome, mint, rad, fly, sick, and mad to indicate something’s cool. Some even used tubular, groovy, and funky. Millennials use dank, lit, drip, dope, and fire.

When I converse with the younger crowd, I can usually keep up by considering the context in which the slang is used. Not this time. My head spun during my latest conversation.

The young woman used words like:

Benched

DTR

Orbiting

Cloaked

Cuffing season

Breadcrumbed

Love bomber

After this baffling conversation, I looked up millennial slang and found several other words I’d never heard before. If you have a millennial character or a young person in your life, this list may help. Keep track of how many are familiar to you.

Romance writers, take note. 😉

Pocketing

When someone pockets you, they’re keeping your relationship secret from family and friends.

Benching

When one romantic partner likes the other enough to keep dating but not enough to have a serious relationship with them. The term comes from sports, where a coach might keep a player on the bench rather than letting them play in the game. In the context of dating, it means giving someone just enough attention to keep them interested without fully committing to a relationship.

DTR

Acronym for Define The Relationship. Gen Z prefers to ease into a relationship. The first stage is the Talking Phase, where potential romantic partners chat online or via text. The talking phase can last for weeks or months before anyone even suggests an actual date, which typically leads to a situationship. Because dating can be confusing as the couple grows closer, one partner might ask the other to Define The Relationship. Are they building an exclusive relationship that may someday lead to marriage? Or do they prefer to keep it casual and date other people, as well?

Situationship

I like this one. It’s clear and to the point.

Situationships occur when two potential partners have ongoing communication, and it’s acknowledged, either directly or indirectly, that they are interested in each other. Super casual and low commitment, it’s a gray area where the two lovers might act like a couple but haven’t explicitly labelled their situationship or agreed on exclusivity.

Sus

Short for suspicious. Something doesn’t sit well for one partner. Anything can be sus. It’s not exclusively for dating.

Ghosting

One partner disappears from the other’s life, but with a twist. In the mid-20th century, we’d ask a family member to answer the phone and say we were sleeping, in the shower, or not home. Then never return the call.

With the invention of the answering machine in the mid-to-late-20th century, we could screen calls by waiting to hear who was calling. In the late ’80s/early ’90s, it became easier to screen calls with caller ID. Today, because smartphones have a “read receipts” option, ghosting is also called R-bombing: You know the person has read your text, but they don’t reply.

Ghostbusting

A ghostbuster is someone who continues to text and call after being ghosted.

Haunting

When an ex won’t return your call or reply to a text but will keep tabs on you through your social media posts.

Orbiting

Orbiting is a bit like haunting but strictly digitally based. After ghosting you, the orbiter stays in your life by orbiting your social media world, liking posts and watching your Stories and/or Reels.

Caspering

This is the kinder way of ghosting someone. They tell their partner they’ll disappear from their life — essentially a breakup, just not in person.

Submarining

When someone has ghosted their partner, they re-emerge later as if nothing had happened. Similar slang is zombieing, because like a zombie, they come back from the dead and re-enter your world without warning.

Cloaking

The harshest form of ghosting, to be cloaked means your partner not only stood you up for a date with no explanation but also refuses to respond to your calls, texts, and has blocked you on dating apps and social media—anywhere you had previously communicated.

Cuffing or Cuffing Season

This refers to the phenomenon where people look to couple up or enter a serious, often exclusive, relationship during the colder months.

Breadcrumbing

Breadcrumbing is the new “leading someone on.” It occurs when someone gives another person just enough attention or communication to keep them interested, without any intention of committing to a genuine relationship. The term “breadcrumbing” comes from the idea of leaving a trail of breadcrumbs, giving the impression of progress or interest while the trail leads nowhere.

Love Bomber or Love Bombing

Love Bombing is used by individuals to gain control over their partner. It involves overwhelming someone with excessive attention, affection, flattery, and gifts early in the relationship to make them feel special and dependent. The aim is to create a strong emotional bond quickly, making it harder for the targeted person to recognize red flags or leave the situationship.

Fishing

Casting many messages out on various dating apps to see who bites.

Simp

A simp is the classic nice guy who will do anything for the girl he likes, only to be sanctioned to the “friend zone.”

Cushioning

Another dating strategy, where someone maintains a roster of potential romantic interests, or “cushions,” while being in a primary relationship. This practice is done to soften the blow or cushion the emotional impact in case the main relationship fails. It involves flirting, texting, or even casually dating multiple people without any serious commitment to them, providing a backup plan to fall back on.

Dry Dating

The days when young people relied on alcohol for liquid courage are long over with more millennials choosing to go stone-cold-sober on a first date, perhaps even for several dates.

Beige Flag

You’ve heard of red flags and even green flags, but a beige flag is the newest slang on the Gen Z dating block. It’s described as something that’s neither good nor bad but makes the other person pause for a minute when it’s noticed and is usually something odd.

Cookie-jarring

The opposite of benching, you see someone regularly, but she hasn’t Defined The Relationship (DTR). The reason is that she’s also secretly seeing someone else. You are being cookie-jarred in case the relationship with the other guy doesn’t work out.

Kittenfishing

A less severe form of catfishing, kittenfishing is when you’ve been fooled into believing the lies a potential date tells you about who he/she/they is. Lies are usually about age (using an old photo), job, height, etc. As soon as you meet in person, the truth is revealed.

Rizz

Rizz is defined as how successful someone is at attracting or flirting with a potential date due to their charismatic personality or silent charm.

Slow Fade

Like ghosting, but in slow motion. The slow fader first becomes less responsive to texts and calls, starts canceling plans, and eventually stops making new plans.

Curving

In Gen Z dating speak, curving describes the act of politely rejecting someone’s advances without explicitly saying “no.” Instead of directly rejecting the person, they respond in a way that subtly signals disinterest or avoids commitment, often through vague or evasive responses.

Catch and Release

Much like fishing, the playboy likes the thrill of the chase but is no longer interested once they have caught the object of their desire.

Serendipidating

This term combines the concepts of “if it’s meant to be” with “the grass is always greener.” Thus, serendipidating means you are putting off a date just in case someone better comes along.

Tuning

Flirting for the sake of flirting without any interest in any type of relationship.

Marleying

Coined by the dating site eHarmony, Marleying is when you are zombied during the Christmas season, specifically. The name comes from the character in A Christmas Carol, Jacob Marley, who haunted Scrooge. Evidently, according to the dating site’s survey, 1 in 10 singles have been contacted by an ex during the holidays.

Flexting

Flexting is defined both as the act of digital flirting as well as the act of “digital boasting.” A flexter exaggerates about who they are, what they do, or how they look. According to market research, men flext more than women, with 63 percent of women who date online saying they’ve met a flexter versus only 38 percent of men.

Peacocking

This is a courtship term used by animal behaviorists: To get a female’s attention, a male peacock displays its elaborate feathers (other animals do this as well). Peacocking means one person shows off to get another’s attention, dressing up in attention-grabbing clothes or colors, shows off musical talents, or throws around money.

Freckling

Think of freckling as a summer fling. As summer turns to fall and your freckles fade, so does your summer romance.

Mosting

Like love bombing, the moster only loves the thrill of the chase and the act of coming on strong. The moster will likely end up ghosting you once he or she has expressed their undying affection.

Devaluing and Discarding

A process used by toxic and abusive people, it’s a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde situation. The relationship is a roller-coaster of kindness followed by cruelty, abuse, and toxicity, followed by kindness again. During the relationship, they break down their partner’s confidence, then discards them, leaving them depleted and confused, wondering where things went wrong. First, he devalues, then he discards.

Hoovering

When a toxic or abusive person wants to get back into your life by offering an empty apology.

Flying Monkeys

A Wizard of Oz reference, a flying monkey is recruited by an abuser to help debase their victim. In the movie, the flying monkeys did the dirty work for the Wicked Witch of the West.

Fauxbae’ing

Fauxbae’ers pretend to be involved with someone when they aren’t even dating. It’s a 21st-century concept because the pretending happens online, over social media.

Stashing

Pretty much the opposite of fauxbae’ing, stashing is when you are dating someone, but they keep you a secret from their friends and/or family, and don’t post about you on social media.

Micro-cheating

Cheating… a little. Whatever that means.

Shaveducking

A young woman’s concern that her attraction to someone was simply because she liked his beard.

When I first read this one, it sounded superficial. But then, I realized I’ve been guilty of shaveducking. Hey, chemistry is a fickle beast. You meet a man with a beard. He’s had it for months, and you love his signature style. Then one day, he shaves and doesn’t look anything like the man you’ve been dating.

Sidebarring or Pubbing

When you’re on a date but spend more time looking at your phone than engaging with your date.

Thirst Trap

A thirst trap might involve one partner intentionally posting seductive or flirtatious photos on social media with the aim of garnering attention or arousing jealousy from their significant other. It could be a way to test their partner’s level of interest or to seek validation and reassurance about their attractiveness and desirability within the relationship.

How many did you know? What slang did you use back in the day? Do you use slang in your books?

If you have a Gen Z character, only use one or two slang words in dialogue. Never in the narrative. Caution: using generational slang will date your book and may confuse some readers. If you venture down this path, make sure the context is clear.

Raptors are some of the most successful predators on the planet. From owls, eagles, and vultures to hawks, falcons, and other birds of prey, raptors are skilled hunters with incredible senses, like binocular vision, that help them detect prey at far distances.

Raptors are some of the most successful predators on the planet. From owls, eagles, and vultures to hawks, falcons, and other birds of prey, raptors are skilled hunters with incredible senses, like binocular vision, that help them detect prey at far distances.

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar.

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar. No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else.

No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else. Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems.

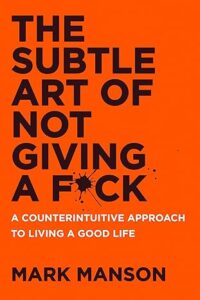

Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems. I stumbled across the subject of The Backwards Law by accident—a happy accident that led me to The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. Excellent book that I devoured in two sittings.

I stumbled across the subject of The Backwards Law by accident—a happy accident that led me to The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. Excellent book that I devoured in two sittings.

The things we tell ourselves we become. It’s not easy to silence the inner critic, but it’s a crucial step in every writer’s life.

The things we tell ourselves we become. It’s not easy to silence the inner critic, but it’s a crucial step in every writer’s life. A friend told me a millennial at work couldn’t understand the clock on the wall. I’ve heard many stories involving rotary phones and cursive writing, but the clock surprised me.

A friend told me a millennial at work couldn’t understand the clock on the wall. I’ve heard many stories involving rotary phones and cursive writing, but the clock surprised me. Every character is the hero of their own story. Even the villain.

Every character is the hero of their own story. Even the villain.