Does the main character in your WIP have a particular skill?

If you could instantly become skilled at something, what would it be?

Photo credit: Christian Wiediger, Unsplash

By Debbie Burke

It sounds important, perhaps a doctor’s office trying to reach a patient, a family member with an emergency. Or it could even be good news like a promotion or award.

Naturally, you want this important—but misdirected—message to go to the right person.

What do you do?

You could call or text the number back and explain that you received the message by mistake, and you want to let them know so they can contact the right person.

But should you do that?

According to the FBI, no.

Why?

Because “wrong number text” scams are on the rise.

When you return the message, you’re thanked profusely. Poor Aunt Tillie is in the hospital and if you hadn’t taken the time to let them know, Aunt Tillie could pass away without seeing her beloved niece or nephew.

They continue the conversation and pretty soon you’re texting like old friends. Therein lies the risk.

The “person” you’re communicating with could be a scammer or even a bot programmed to deliver appropriate-sounding responses.

According to the FBI: “The scammers behind the wrong number text messages are counting on you to continue the conversation. They want to exploit your friendliness. Once they’ve made a connection, they’ll work to become friends or even cultivate a remote romantic relationship. It’s all a ruse, designed to get you to relax your mistrust so you’ll be more susceptible to falling for their scam, such as a cryptocurrency investment or many others targeting victims.”

What should you do if you receive a text meant for someone else?

The FBI advises, “Don’t respond.”

It’s a sad world when common decency, kindness, and courtesy are turned against people and used to take advantage of them. But that’s where we are.

Watch out for older family and friends who often fall victim to scams like this.

Writing Things Right

Terry Odell

My second cataract surgery was yesterday, and if everything went as smoothly as the first one did, I should be around to respond to comments.

I’m not a fan of the old “Write What You Know,” mostly because if I followed that guideline, I’d bore my readers (and myself) to death. “Write What You Can Learn” always made more sense to me.

I’m not a fan of the old “Write What You Know,” mostly because if I followed that guideline, I’d bore my readers (and myself) to death. “Write What You Can Learn” always made more sense to me.

The problem arises when you’re clueless that you don’t know something and merrily write along, enjoying the story.

Hint: Readers don’t like inaccuracies.

In Finding Sarah, I needed a way to keep her from doing the obvious—taking the bad guy’s car keys and driving away after she bonked him on the head. I gave the car a manual transmission, and parked it headed against a tree. Pretty clever, right? A wise critique partner told me that the Highlander I’d chosen for the vehicle (inside nod to my writing beginnings) didn’t come with a manual transmission. I had no idea you couldn’t get every car in whatever configuration you wanted.

Then there are the gun people.

Then there are the gun people.

Robert Crais made the unforgiveable “thumbed the safety off the Glock” error in a book, and I asked him if readers gave him flak about it. His response? “Every. Damn. Day.”

John Sandford had the same issue once when he’d been using the term “pistol” and decided he wanted to get specific, so he changed it to a Glock, not realizing he’d already had a character releasing the safety. His response? “It was an after-market addition.”

I know darn well I’m clueless about weaponry, so I do my homework before arming my characters.

What about other areas? The current manuscript, Deadly Adversaries, seemed to be throwing roadblocks every time I wrote a scene. Wanting to make sure what I’d written was at least plausible, I asked my specialist sources.

***Note. It’s important to rely on reliable sources if you want to get things right. As Dr. Doug Lyle said in a webinar: Google something you know a lot about, and see how many different explanations you get. The internet can be helpful, but don’t take it as gospel.

***Note. It’s important to rely on reliable sources if you want to get things right. As Dr. Doug Lyle said in a webinar: Google something you know a lot about, and see how many different explanations you get. The internet can be helpful, but don’t take it as gospel.

Sometimes solutions are easy. If I have a fight scene, I give my martial arts daughter the basics, letting her know who’s fighting, who’s supposed to win, if anyone’s injured, etc. She comes back with the basic choreography and I put it into prose.

Sometimes solutions are not quite so easy. I had a great scenario for immobilizing my victims. I ran it by my medical consultant, and he said, Nothing is impossible but this is as close as it gets. The drug would have to absorb through the skin in very small doses and very quickly. Cyanide and sodium azide can do that but they are both deadly—very quickly. I’d find another way to incapacitate your character.

Back to the drawing board.

In my Blackthorne, Inc. series, which center around a totally made up high-end security and covert ops company, I can give my characters technology, equipment, and just about anything else they need. In and out like the wind is their motto. The scope of plausibility is wide.

Not so with my Mapleton books. They’re contemporary police procedurals at heart, and I want them to be as accurate as possible. To this end, I ran a couple of scenes by my cop consultant. He told me my headlight fragments probably weren’t going to help the cops identify the vehicle involved. Okay, I could work around that.

The next question was about my cops questioning someone in jail. Eye opener here. After some what if this’s and what about that’’? the bottom line: usually what you get at the time of the arrest is the last bite at the apple. So, the information I needed my cops to discover had to come from someone else instead of going to the jail to interview him after he was arrested.

Back to the drawing board again.

The biggest—and most troublesome—stumbling block in this book was that the story played out in numerous jurisdictions. I couldn’t have my cops go to their suspects, or even witnesses, without a local LEO along, or at least notified.

Once they knock on the character’s door, they’re just civilians. Outside of their jurisdiction, they’re not cops. What I’d written was just plain wrong and my decent, play by the rules Mapleton cops would never have done it. If they had, they could have been charged with false imprisonment.

So much for my exciting climactic scene! It would be nothing but paperwork and judges and extraditions. Nothing edge-of-the-seat in those scenarios.

As my cop friend put it, Funny how most people don’t get how complicated the laws make everything.

I went back to the drawing board a lot on these scenes.

By the time we’d had dozens of back-and-forths, and I’d reached a plausible, “that could work” resolution, he said:

I’m laughing. You try to do it right. See how boring Hollywood would have been it they had to keep within that pesky Constitution. It stood in my way many times.

What about you, TKZers? How do you make sure you get things right? Have you ever not realized you thought you knew something and then found out you didn’t? Do you write first, fix later, or research first? Or ignore the issue altogether–it’s fiction, after all.

Available Now

Available Now

Deadly Relations.

Nothing Ever Happens in Mapleton … Until it Does

Gordon Hepler, Mapleton, Colorado’s Police Chief, is called away from a quiet Sunday with his wife to an emergency situation at the home he’s planning to sell. A man has chained himself to the front porch, threatening to set off an explosive.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Photo credit: Wikimedia

By Debbie Burke

Side note: Who wants to apply for the job to create snappy government acronyms?

A reported $22,000,000 is being used to develop textiles that are washable, breathable, flexible, and comfortable with smart technology woven right into the fabric. Soon shirts, pants, socks, and, yes, even underwear may be able to record photos, video, audio, and geolocation data.

Instead of body cams and handheld devices, law enforcement personnel or intelligence gatherers simply wear smart clothing that performs similar tasks.

According to IARPA, components include “weavable conductive polymer ‘wires’, energy harvesters powered by the body, ultra-low power printable computers on cloth, microphones that behave like threads, and ‘scrunchable’ batteries that can function after many deformations.”

The result is surveillance and recording capability that is undetectable, as inconspicuous as a tiny slub in the material of a shirt or pants.

The developer of SMART ePANTS is Dr. Dawson Cagle. A July, 2023 article in Homeland Security Today quotes Cagle:

“As a former weapons inspector myself, I know how much hand-carried electronics can interfere with my situational awareness at inspection sites,” Dr. Cagle said. “In unknown environments, I’d rather have my hands free to grab ladders and handrails more firmly and keep from hitting my head than holding some device.”

He adds: “We’ve moved computers into our smart phones. This is the chance to move computers into our clothing and help the IC, DoD, DHS, and other agencies improve their mission capabilities at the same time.”

Cagle says his father’s diabetes was the inspiration for the smart textile technology he’s working on. He describes how his father used to perform five manual tests a day to track his blood sugar. Now, automatic monitors are incorporated into smartphones for immediate testing anytime.

So, the wearer may also be watched.

The feds aren’t the first to pioneer smart textiles.

Underwear with embedded electrical stimulators is used to prevent bed sores.

Smart clothing is available to consumers to track biometrics for health and fitness monitoring and even to improve yoga form.

At IARPA, the testing process for smart textiles is divided into three parts: 18 months to “build it”; 12 months to “wear it”; 12 months to “wash it.”

IARPA is the government’s “Gee Whiz” department that experiments with new possibilities for cutting edge technology. IARPA “invests federal funding into high-risk, high reward projects to address challenges facing the intelligence community.”

Sometimes their experiments succeed; sometimes they’re costly failures.

According to The Intercept, Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit (TALOS) is one such example. In 2013, IARPA inventors went to work on wearable material that could transform into protective armor for soldiers, similar to the “Iron Man” suit that Robert Downey wore in the 2008 film.

In a 2013 article on Mashable:

Norman Wagner, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Delaware, is using nanotechnology to create a liquid-ceramic material. The moment the thin, liquid-like fabric is hit with something — say, a bullet — it would immediately transform into a much harder shell.

“It transitions when you hit it hard,” Wagner told NPR. “These particles organize themselves quickly, locally in a way that they can’t flow anymore and they become like a solid.”

After six years of research at a cost of $80,000,000, The Intercept reports TALOS was shelved in 2019 without producing a usable prototype.

As writers, we understand how many times our stories fail before being accepted by an agent or publisher. Fortunately, the cost of our experiments rarely runs into millions or billions.

The concept of surveillance clothing revs up the imaginations of thriller, espionage, and sci-fi writers. Books and films have a long history of providing fodder for future inventions. Our jobs as writers include being visionaries and prophets.

Now the only question left to answer about SMART ePANTS: Boxers or briefs?

~~~

TKZers: Have you used “gee whiz” inventions like SMART ePANTS in your fiction?

What story situations can you imagine where wearable surveillance garments play a role?

Have you invented a product or concept that could come to pass in the future?

“Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.” ― Leonardo da Vinci

* * *

In yesterday’s TKZ post, James Scott Bell deconstructed the movie The Fugitive and shared some lessons from it. Today, I want to look at a very different movie for a different reason.

The1957 film The Spirit of St. Louis is the story of Charles Lindbergh’s historic flight from New York’s Roosevelt Field to Le Bourget Field in Paris. Lindbergh hoped to win the $25,000 Orteig Prize by being the first to fly non-stop from New York to Paris, but this was no easy task. Six men had already died trying.

Now you would think a movie that follows a thirty-three-hour flight over the ocean would be a huge bore, but the filmmakers came up with a way to present it that engages the audience. Jimmy Stewart in the role of Charles Lindbergh lends authenticity, humor, and occasional hilarity to the film.

Like most stories, this movie is divided into three parts.

Act One covers the night before the flight when Charles Lindbergh is lying awake, dreading the sound of raindrops plunking against the window of his hotel room. This 53-minute act fluctuates between scenes of Lindbergh’s insomnia and flashbacks to his experiences as a U.S. Post Office airmail pilot, and other humorous scenes. From the story-telling point of view, this act provides movie-goers with knowledge of Lindbergh as a man, not a legend. He comes across as a likeable, shy, and determined young pilot.

Act Two recounts the take-off scene in seventeen minutes. I’ll come back to this in detail below.

Act Three is another long segment that follows the flight across the ocean and the landing in Paris, alternating between scenes of the sleep-deprived Lindbergh’s efforts to stay awake, a scary moment when ice forms on the wings and threatens to bring the plane down, and more flashbacks of his life as a barnstorming pilot and as a cadet with the United States Army Air Service.

* * *

But it’s Act Two where the real tension lies. Even though we all know the outcome, I find myself holding my breath whenever I watch the scene.

It begins when Lindbergh arrives at Roosevelt Field on the morning of May 20, 1927. The conditions are awful. The rain has made the field a muddy mess, and the fog renders a successful takeoff over the very tall trees at the end of the runway unlikely. Frank Mahoney, the owner of the Ryan Aircraft Company which built the plane, advises Lindbergh to wait and try again later. But the young pilot thinks there may be a chance, and he places a white marker at a certain point on the side of the sloppy runway. If he tries the takeoff and reaches the marker before the plane gets off the ground, he says he’ll abort the effort.

Only Lindbergh can make the Go/No-Go call, and he knows the odds are not good. He suits up, climbs into the cockpit, and does the runup. You can see the doubt on his face when he raises his hand in a goodbye gesture to the small group of people who came to see him off.

No one would blame him if he decided to wait. But you can almost hear his inner voice say, “This is your moment. Don’t let it pass you by.”

At approximately the exact middle of the movie (and I know James Scott Bell will love this), Lindbergh finalizes his decision by calling out the words that will start the plane forward: “Pull the chocks.” There will be no turning back.

A group of men actually push the plane to get it moving in the muck, and the little aircraft, heavy with fuel and struggling against the poor-to-horrible weather conditions, slogs its way down the field toward a line of trees that look increasingly ominous.

It would be hard to describe the scene of the actual takeoff, so I’ll let you watch this three-minute clip instead:

* * *

Charles Lindbergh was passionate about his chosen profession, and he put in the time to learn his craft. He had honed his experience through years of barnstorming, flying airmail routes, and giving lessons. He went through training with the United States Army Air Service at Brooks Field in Texas and earned his Army pilot’s wings and a commission as a second lieutenant in the Air Service Reserve Corps.

But even though he was the sole pilot of The Spirit of St. Louis when he flew across the ocean, Lindbergh’s effort would have been impossible without the support and knowledge of many others.

A group of St. Louis businessmen had financed the building of the aircraft. The owners and employees of the Ryan Aircraft Company supplied the experience and commitment to design the plane that could make a journey of almost four thousand miles. Lindbergh couldn’t have lifted off the ground without their help.

* * *

It seems I find an analogy to writing in just about everything these days, and it’s easy to see the connection between lifting off on a flight where the conditions aren’t perfect and launching a novel.

As everyone here knows, the preparation for bringing a novel to publication is long and difficult. And it isn’t just the hard work of meeting the weekly quota. The background of life experiences, craft books, writing courses, and blogs like The Kill Zone, all combine to prepare the writer for his/her effort.

In most books, only the author’s name is on the cover. But the product is usually the result of many people who willingly came alongside to make the book a success. Friends, editors, mentors, beta readers, endorsers, experts, and supporters from other areas pour their knowledge and expertise into the project.

But at some point, the author has to make the last preparations and commit to the flight. A new book launch may not be as risky as taking off in an airplane to fly a course no one has flown before, but to the author, it is just as exciting.

* * *

So there you have it. Today is launch day for Lacey’s Star: A Lady Pilot-in-Command Novel. It’s been a long, bumpy runway. Now we’ll see how she flies.

* * *

So TKZers: Have you launched a book recently? Tell us about it. What advice do you have for authors about making a book launch successful?

* * *

PULL THE CHOCKS!

Private pilot Cassie Deakiin is smart, funny, and determined. She can land a plane safely in an emergency, but can she keep her cool when confronted by a murderer?

Lacey’s Star: A Lady Pilot-in-Command Novel began flying off the shelves today. $1.99 at Amazon Barnes & Noble Apple Books Kobo Google Play

Have a nice flight, Cassie.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

The Fugitive (1993) is one of my all-time favorite thrillers, both to watch and to teach. So many great lessons can be drawn from it. I’ll share a few with you today.

The Fugitive (1993) is one of my all-time favorite thrillers, both to watch and to teach. So many great lessons can be drawn from it. I’ll share a few with you today.

Based on the hit TV show from the 1960s, it’s the story of respected surgeon Dr. Richard Kimble (Harrison Ford), who comes home one night to find his wife dying at the hands (or rather, hand) of a one-armed man. Kimble fights with him, but the man gets away. Kimble tries to save his wife, to no avail. He is convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. He escapes. A crack team led by Deputy U.S. Marshal Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones) sets out to track him down.

The story question: Can Kimble keep ahead of the law long enough to prove his innocence by finding the one-armed man?

The story question: Can Kimble keep ahead of the law long enough to prove his innocence by finding the one-armed man?

Structure

At a little over two hours, the movie is a terrific study in the power of structure. The film would not be nearly as engaging if it did not hit the right signposts at the right time.

Thus, we get the opening disturbance in the very first shot: a TV reporter stands outside the Kimble home, where the police are investigating the death of Kimble’s wife. Kimble is taken to the police station and questioned by two detectives. He thinks it’s as a grieving husband, but soon it dawns on him that they consider him the chief suspect.

Yeah, I’d be disturbed, too.

Lesson: Start your story by striking a match, not by laying out the wood. (h/t John le Carré.) You have plenty of time for backstory later. Readers will happily wait for fill-in material if they’re caught up in immediate trouble.

On we go through Act 1: Kimble is convicted, sentenced, put on a prison bus. A couple of convicts stage an uprising, the driver is shot, a guard is stabbed, the bus tumbles off the road and onto railroad tracks…just as a train comes right for it!

This is one great action sequence. The convicts and one guard get the heck out of the bus. But Kimble stays behind to help the wounded guard, gets him out a window, and jumps one second before the train hits the bus. That would be enough for most writers, but not for screenwriters Jeb Stuart and David Twohy. Half the derailed train breaks off and comes right at the fleeing Kimble! He barely avoids being crushed.

Lesson: When you have a great action sequence, or suspenseful scene, stretch the tension as far as you can. Ask: What else could go wrong? What could make things worse?

At the crash site, while local law enforcement is botching things, Deputy U.S. Marshal Sam Gerard arrives with his crack team. He figures out what’s going on, orders roadblocks, and announces, “Your fugitive’s name is Dr. Richard Kimble. Go get him.”

Boom! We are ¼ of the way into the film, and the Doorway of No Return has just slammed shut. Kimble cannot go back to his ordinary life. He must face the “dark forest” (almost literally) at the heart of myth. Survive or be killed.

Lesson: In a novel, my view is that the Doorway should happen no later than the 1/5 mark. Otherwise, things start to drag.

Solid structure is a beautiful thing. Far from being a hindrance, it is the most powerful way to share the story in your head and heart with an audience. See: “Story and Structure in Love.”

The Mirror Moment

Act 2, of course, is a series of rising action, mostly of Kimble barely keeping escaping his pursuers. At the exact halfway point, where we would expect to find it, is the Mirror Moment.

(If this term is unfamiliar to you, I’ve written a book about it. But lest you think I’m only interested in money (I am interested in it, just not only interested in it) you can check out a couple of TKZ posts here and here.)

As I explain in my book, there are two types of mirror moments: 1. The character looks at himself and asks questions like, “Who am I? What have I become? Am I going to stay this way?” It’s an internal gaze. 2. The character looks at his situation and thinks, “I’m probably going to die. There’s no way I can survive this.” This is an external look.

The second kind is what we have in The Fugitive. In the middle of the film Kimble has rented a basement room from a Polish woman. He’s using it as a base of operations to sneak into Cook County hospital. He wants to access the records of the prosthetics wing to get a list of patients with artificial arms.

In the mirror scene, Kimble is awaked from slumber by the sound of police swarming the house. Kimble looks for a way to escape, but there is none. He’s done for!

Only it turns out the cops are there to nab the Polish woman’s drug-dealing son.

Only it turns out the cops are there to nab the Polish woman’s drug-dealing son.

As the police lead him away, Kimble has a small breakdown. He’s thinking, “I can’t possibly win against these odds. I’m as good as dead.”

Lesson: No matter how you write, via outline, winging it, or something in between, take some time early in the process to brainstorm possible mirror moments, of both varieties. Push yourself past the familiar. Inevitably, one of them will feel just right. It will become your guiding light for the entire novel.

To get us into Act 3, we need a Second Doorway. This is either a setback or crisis, or major clue/discovery. It should happen by the ¾ mark, and in The Fugitive it does. I won’t give the spoiler here, but suffice to say it’s the major clue implicating the villain. Now the Final Battle becomes inevitable.

Pet the Dog

This is such a great way to increase the audience bond with the hero. It’s a scene or sequence in Act 2 where the hero takes time to help someone more vulnerable than he, even at the cost of making his situation worse. The Fugitive has one of the best examples you’ll ever see.

Kimble is disguised as a hospital custodian. He’s accessed the prosthetics records he needed. As he’s leaving he walks along the trauma floor. All sorts of triage patients being tended to. He notices a little boy groaning on a gurney. A doctor orders a nurse to check on the boy. The nurse gives him a cursory look. Kimble is aghast. He knows there’s something wrong here.

The doctor reappears and asks Kimble to help out by taking the boy to an observation room. Kimble wheels him away, checking out the X-ray as he goes. He asks the lad a few questions about where it hurts, then changes the orders and gets the boy to an operating room for immediate attention.

The doctor reappears and asks Kimble to help out by taking the boy to an observation room. Kimble wheels him away, checking out the X-ray as he goes. He asks the lad a few questions about where it hurts, then changes the orders and gets the boy to an operating room for immediate attention.

That’s a success, but in a thriller any success should be followed by some worse trouble.

Turns out the doctor saw Kimble look at the film, and confronts him as he’s walking out. She rips off his fake ID and calls for security. More trouble! (This sequence has a favorite little moment. As Kimble is rushing down the stairs to get away, he brushes past someone coming up. He looks back and says, “Excuse me.” Kimble is so fundamentally decent he apologizes even as he’s running for his life!)

Lesson: Create a character the hero can help, even in the midst of all his troubles (e.g., Rue in The Hunger Games). The deepening bond this creates with the reader is so worth it.

Character

The Fugitive features a protagonist and antagonist who are both sympathetic. Kimble, of course, is a devoted husband wrongly convicted of murder. Sam Gerard is a great lawman who doggedly pursues justice.

Lesson: You don’t need a traditional villain to carry your thriller. In The Fugitive, it’s two good men with agendas in direct conflict. The true villain reveal is at the end.

Dialogue

Many of the great lines in the movie were actually improvised. The most famous is from the spillway scene. Kimble has a gun on Gerard. Kimble says, “I didn’t kill my wife!” And Gerard says, “I don’t care!” Tommy Lee Jones came up with that.

Many of the great lines in the movie were actually improvised. The most famous is from the spillway scene. Kimble has a gun on Gerard. Kimble says, “I didn’t kill my wife!” And Gerard says, “I don’t care!” Tommy Lee Jones came up with that.

Another perfect line not in the script is just after the train derailment. Another prisoner, Copeland, a stone-cold killer, helps Kimble to his feet. He says to Kimble, “Now you listen. I don’t give a damn which way you go. Just don’t follow me. You got that?”

As he’s pulling away Kimble says, “Hey Copeland.” Copeland turns around. Kimble says, “Be good.” Another mark of his decency, like when he said, “Excuse me.”

Love it! You can get a bestselling book on the subject, but the gist is simple:

Lesson: Great dialogue is the fastest way to improve any manuscript.

Over to you for discussion. And as a bonus for reading all the way to the end of this lengthy post, let me mention that Romeo’s Way, the novel that won the International Thriller Writers Award, is FREE, today only. Grab it here.

I began reading thrillers during my sophomore year in high school. One of the first I read was Thomas Harris’s Black Sunday, a pulse-pounding novel that was a race against time to stop a diabolical terrorist attack at the Super Bowl. Another thriller I read then was Paul Erdman’s The Silver Bears, which featured kind of scheme, one to corner the silver market.

I burned through both novels in just a couple of days. The stories were very different, yet the suspense in each kept me turning pages, unable to stop until the end.

Today’s Words of Wisdom looks at suspense. Jordan Dane gives you a few questions to ask yourself during editing in order to make your book more suspenseful, while Joe Moore discusses how having too much action can hurt suspense, and PJ Parrish considers formulas for suspense and surprise.

The full versions are linked from the bottom of their respective excerpts and very much worth reading in full.

If you’ve made it through your first draft of a novel and want to edit for suspense and pace to give your book a page-turner feel, below are questions to ask yourself.

1.) Did you begin your story at the right point? Opening in the middle of action is an attention getter, but don’t spoil it with excessive back story. You can also add an element of mystery or intrigue to your opener that will draw readers in if action doesn’t exactly fit your story, but remember that less is more. You’ll always have the opportunity to weave in back story if it’s necessary as the story progresses. It might be helpful to ask yourself if the start of your book is the last possible moment before your main character’s life is changed. Change is an excellent starting point. I sometimes start the story where I think it should, then consider adding either an inciting incident by way of Prologue or a standalone jumpstart to the story that precedes where I began.

4.) Do you have flashbacks that work or drag down the pace? Flashbacks can be tricky. We’ve all read books where flashbacks drive the novel and do it effectively, but make sure yours have a purpose and build on the tension of the main plot going forward. Flashbacks aren’t just another way to sneak in back story. Give the reader insight into the main plot with an effective and brief look into the motivation of the characters, if the flashbacks are necessary.

6.) Do you use foreshadowing to your advantage or is it a detriment that deflates your tension? The right balance of foreshadowing can add a sense of pace to your story. It can propel your storyline from scene to scene, but too much can burst the bubble of any mystery and telegraph your punches. Sometimes I look at my scene endings and see if I can stop them sooner at a more critical suspense moment. Or I split up an action scene at the bottom of a chapter and carry it over to the top of the next chapter. This simple idea of splitting scenes or cutting them off at a more appropriate spot can add a sense of pace, without any major rewrites.

Jordan Dane—March 7, 2013

I’ve found that one of the mistakes beginning writers often make is confusing action with suspense; they assume a thriller must be filled with action to create suspense. They load up their stories with endless gun battles, car chases, and daredevil stunts as the heroes are being chased across town or continents with a relentless batch of baddies hot in pursuit. The result can begin to look like the Perils of Pauline; jumping from one fire to another. What many beginning thriller writers don’t realize is that heavy-handed action usually produces boredom, not thrills.

When there’s too much action, you can wind up with a story that lacks tension and suspense. The reader becomes bored and never really cares about who lives or who wins. If they actually finish the book, it’s probably because they’re trapped on a coast-to-coast flight or inside a vacation hotel room while it’s pouring down rain outside.

Too much action becomes even more apparent in the movies. The James Bond film Quantum Of Solace is an example. The story was so buried in action that by the end, I simply didn’t care. All I wanted to happen was for it to be over. Don’t get me wrong, the action sequences were visually amazing, but special effects and outlandish stunts can only thrill for a short time. They can’t take the place of strong character development, crisp dialogue and clever plotting.

As far as thrillers are concerned, I’ve found that most action scenes just get in the way of the story. What I enjoy is the anticipation of action and danger, and the threat of something that has not happened yet. When it does happen, the action scene becomes the release valve.

I believe that writing an action scene can be fairly easy. What’s difficult is writing a suspenseful story without having to rely on tons of action. Doing so takes skill. Anyone can write a chase sequence or describe a shoot-out. The trick is not to confuse action with suspense. Guns, fast cars and rollercoaster-like chase scenes are fun, but do they really get the reader’s heart pumping. Or is it the lead-up to the chase, the anticipation of the kill, the breathless suspense of knowing that danger is waiting just around the corner?

Joe Moore–September 18, 2013

There’s the old Hitchcock formula: 1. A couple is sitting at a table talking. 2. The audience is shown a time bomb beneath the table and the amount of time left before it explodes. 3. The couple continues talking, unaware of the danger. 4. The audience eyes a clock in the background.

The surprise, Hitchcock said, didn’t come from the bomb itself; it came from the tension of not seeing it.

Speaking of formulas, there actually is one for suspense:

Suspense: t = (E t [(µ¿ t+1 – µ t)²])½

I didn’t make this up, believe me. It was created by Emir Kamenica and Alexander Frankel of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. It is basically an equation about time and expectations: “t” represents the period of time a moment of suspense is occurring, “E” is the expectations at that time, the Greek mu indicates your belief in the next thing to happen, the +1 is your belief in the future, the tilde represents uncertainty, and the subtracted mu is the belief you might have tomorrow.

That made your brain hurt, right? Mine, too. But hey, you sat through my football metaphor, so stay with me a little longer. The Chicago guys also developed a formula for surprise, which is easier to stomach for us math-challenged types. It boils down to this: what your beliefs are now minus what your beliefs were yesterday.

Their paper “Suspense and Surprise” (co-written with Northwestern University economics professor Jeffrey Ely) was published in the “Journal of Political Economy.” It was inspired by their observation that in various types of entertainment – gambling, watching sports, reading mysteries – people don’t really WANT to know the outcome.

What they DO want is a “slow reveal of information.” As one of them put it in an article in the Chicago Tribune: “To be exciting, we found that things need to get dull.”

Information revealed over time generates drama in two ways: suspense and surprise. Suspense is all about BEFORE, ie something is going to happen. (the ticking bomb under the chair). Surprise is about AFTER, ie you’re surprised that something unexpected happened. (the bomb didn’t go off!) If you are led to believe one thing is going to happen (Broncos will win!) but then are surprised by the unexpected (Colts prevail!) that can be pretty powerful.

So how do you translate this to your own writing?

I’ll let Kamenica explain. He goes back to the Hitchcock formula: “Let’s take that idea and ask a mathematical question: How much suspense can you possibly generate?’ Putting that bomb there generates suspense, but how long can you leave it there? Can you leave it the duration of the movie? Or is that boring? Once you put it there, when do you decide for it to go off? One-third of the way through? One-half? If I am invested, as a viewer, how frequently should uncertainty be resolved? You have a threat, information that (a bomb) will explode, then it gets resolved, the movie continues. But will these people survive the next danger? How often can you do that — change an audience view?”

He has the answer, of course: Three times.

“Say you are writing a mystery,” Kamenica goes on in the Chicago Tribune article, “Zero twists is bad. And one thousand twists is also bad — again, for something to be exciting, it must occasionally become boring. So, three. The math delivers surprisingly concrete prescriptions. That number is constrained to a stylized view, characteristic mystery novel: Is it the maid or butler who did it? Does the protagonist live or die? A novelist must lead you in one direction then …”

Added his colleague Frankel: “The thing is, we also found that you can’t really have a definite number of twists. Three is average. Yet if you know there are three twists, those twists are not actually twists — you are now waiting for the twist.”

And that, to me, is the major lesson here. Not that your book must conform to a three-twist formula. Because if your readers know you have three twists, you’ve lost the suspense. The lesson, to me, is less might just be more.

PJ Parrish—November 10, 2015

***

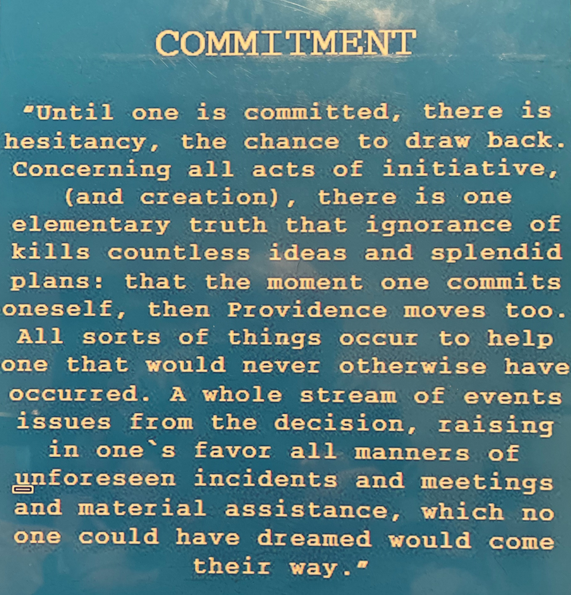

I don’t know about you, but I’m a sucker for motivational quotes and affirmations. I find inspiration in sourcing words of wisdom, copying them, and pasting them into my scrapbook which I keep on top of my desk. I also have a lot of little yellow Post-Its with scribbles of sensible sayings stuck all around.

I have three daily affirmations that I faithfully read every morning. They remind me of my overall place in existence and how fast time goes by. They’re words from the Stoics or at least those who have Stoic-like attitudes. Allow me to open my book and share some of what I’ve collected.

“Contempt for failure.”

“Did I show up dressed today?”

“Memento Mori” ~Marcus Aurelius

“Ya gotta wanna.” ~Jimmy Pattison

“To understand is to know what to do.”

“Focus. Cut the noise. Double the results.”

“Invest the Time. Do the work. Tell the truth.”

“This, too, shall pass away.” ~Abraham Lincoln

“Overcome resistance. Trust the muse.” ~Stephen King

“Three common traits of winners. Desire. Determination. Confidence.”

“You don’t really understand something until you can build it.” ~Richard Feynman

“If you do what everyone else is doing, you shouldn’t be surprised to get the same results. Different outcomes come from doing things differently.”

“The long game wins come from repeatedly doing hard things today that make tomorrow easier.”

“Let us prepare our minds as if we’d come to the very end of life…the one who puts the finishing touches on their life each day is never short of time.” ~Seneca

“Compound interest is the most powerful force in the universe. It’s the dogged, incremental, constant progress over a very long time.” ~Albert Einstein

“There are those who watch things happen, those who wonder what happened, and those who make things happen. Strive to be one of those who make things happen. If you show others what you can do, they will respect you far more than if you had simply told them what you’d done. Anyone can quarrel with words, but actions speak for themselves.” ~Tommy Lasorda

“Failure seems to be nature’s plan for preparing us for great responsibilities. If everything we attempted in life were achieved with a minimum of effort and came out exactly as planned, how little we would learn—and how boring life would be! And how arrogant we would become if we succeeded at everything we attempted. Failure allows us to develop the essential quality of humility. It is not easy—when you are the person experiencing failure—to accept it philosophically, serene in the knowledge that this is one of life’s great learning experiences. But it is. Nature’s ways are not always easily understood, but they are repetitive and therefore predictable. You can be absolutely certain that when you feel you are being most unfairly tested, you are being prepared for great achievement.”” ~Napoleon Hill

“I believe that life operates at two levels. The higher level if the muse level—the level of your calling. The lower level is our material plane. On that plane is the force I call Resistance with a capital R. That’s there to stop us from reaching the higher level. The purpose of discipline is that discipline is what takes you to that higher level. That’s why you have to have it—discipline. You can’t wish your way to it. You can’t chant your way there. You can’t—that book The Secret—vibe or manifest your way there. The law of attraction is bullshit. It’s not going to get you there. The only way you get there is through hard and disciplined work. You got to punch your ticket and pay the price.” ~Steven Pressfield

“Doing your best isn’t about the result. You know you did your best before you show up. Over the long term, the long game, the average person who constantly puts themselves in a good position beats the genius who puts themselves in a poor position. And the best way to put yourself in a good position is with good preparation.”

Impossible is just a big word thrown around by small men who find it easier to live in a world they’ve been given than to explore the power they have to change it. Impossible is not a fact. It’s an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration. It’s a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing.” ~Muhammad Ali

“One of the biggest keys to success at anything is believing you can figure it out as you go along. A lot of people won’t start until they figure it out. And because most hard things can’t be figured out in advance, they never start.” ~Richard Feynman

“Any dominating idea, plan, or purpose held in the conscious mind through constant repetitive thought and emotionalized by the subconscious and acted upon by whatever natural and logical means may be available.” ~Napoleon Hill

“Ninety percent of success can be boiled down to consistently doing the obvious thing for an uncommonly long period of time without convincing yourself that you’re smarter than you are.”

“The Formula: The courage to start. The discipline to focus. The confidence to figure it out. The patience to know progress is not always visible. The persistence to keep going, even on the bad days.”

“Success is that place in the road where preparation and opportunity meet, but too few people recognize it because too often it comes disguised as hard work.”

“If you’re the smartest person in the room, you’re in the wrong room.” ~Jordan Peterson

“Anyone can make the simple complicated. Creativity is making the complicated simple.”

“Pro golfers have learned to miss their shots by narrower margins than amateurs.”

“Avoiding stupidity is easier than seeking brilliance.” ~Charlie Munger

“Being successful is easy. Staying successful is hard.”

“An ounce of action is worth a ton of theory.”

What about you Kill Zoners? Do any of these clips resonate with you? How about sharing one, two, three, or more of your own?

We talk about treating the process of writing as if it were a job a job, we talk about quotas, we talk about pressing through to completion on a project. As November approaches, bringing with it the stress of NaNoWriMo to compete with the other stresses of what for many is the most stressful time of year, some of you will be pounding your fingers bloody on the keyboard in effort to produce the 50,000 words that Club Nano has declared to be the goal of the 30-day writing spree.

What we don’t talk about very much is the need to enjoy the ride. It’s important to set goals and achieve them, but it’s also important to cut yourself a break and realize that life happens. If you’re adhering to the adage to treat writing as if it were a job, remember that most desk jobs bring the perquisites of sick leave and vacation time. Meeting a self-imposed deadline is nowhere near as important as attending your kid’s soccer game or giving the puppy a half hour of Frisbee frolic.

If you’re not under a legal contract to produce a work by a date certain, then a date approximate is a fine substitute. Yes, it’s important to plow through the muddled middle to complete your project, but if your February 1 deadline slips to March 15, so what? If you look back on the week and you find that you only wrote 300 words–or no words at all–of your 7,500-word goal, the Earth will remain on its axis. In fact, the world will be a better place if those squandered words paid for a smile from a family member.

I’m not suggesting laziness or sloth. I’m suggesting balance.

Fifteen years ago, more or less, I sat on a panel at Magna Cum Murder in Muncie, Indiana, when the rookie writer to my left–a practicing psychologist, no less–told this room full of aspiring scribes that in order to succeed in the publishing business, you have to be willing to sacrifice everything. Specifically, she spoke of missing family events and vacations. Failure awaited any writer who looks away from their publishing goals even for a moment. When she was done, every molecule of happiness had disappeared from the room as the newbies furiously took notes.

Mine was the next turn to speak, and I started with, “For God’s sake, it’s only a story. We’re not curing cancer here, we’re making stuff up and playing with our imaginary friends. It’s not worth sacrificing any of that. The instant that make believe feels more important than real-life relationships is the instant you need to stop writing and re-evaluate your choices.”

It’s no secret that creative types frequently eat shotguns and down piles of pills. I can’t speak to the reasons behind that, but damaged relationships are often contributing factors. If you’re a spouse, you have a commitment to the relationship you chose. If you’re a parent, you have a commitment to a human being you created. Those come first. Hard stop.

If you’re a teenager or young adult, you have an obligation to yourself to live more of your life out in the word than inside your head. Collect experiences that will serve your writing well into the future.

When you do sit down to write, enjoy the experience and celebrate what you accomplished. Don’t get distracted by what you didn’t do on the page, and instead concentrate on what you did do in the world.