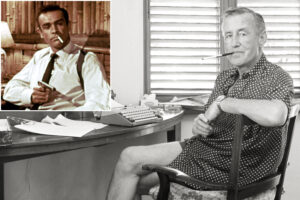

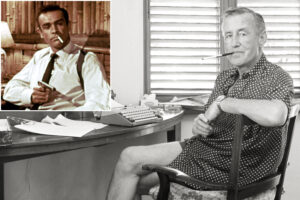

If I could host one guest on The Kill Zone, it’d be Stephen King. That’s not likely to happen, just as it’s not going to happen that I live-host Ian Fleming who created the immensely successful James Bond spy thriller brand. Ian Fleming has been gone from our writing, reading, and viewing world since 1964 — one year after he wrote a masterful essay on his commercial writing approach.

However, I was net-surfing the other night when I stumbled upon this 58-year-old gem titled Ian Fleming Explains How To Write A Thriller, Circa 1963. I read it, reread it, and read it again. “This has to be shared on TKZ,” I said to myself. Then I mumbled about being criticized for plagiarism, so I thought I’d paraphrase it, or edit it, or modify it in some way to maybe shorten it up or put my own twist to it.

“Hang on here!” I said with second thoughts. “Who the hell am I to interfere with thriller writing advice taught by Ian Fleming, told directly in Ian Fleming’s voice, that he intentionally left for the world?” So whack my pee-pee for cut & paste violation, but this piece needs sharing. Here’s the complete and unabridged (shaken, not stirred) 1963 version of How To Write A Thriller by the one and only Ian Fleming:

— — —

“The craft of writing sophisticated thrillers is almost dead. Writers seem to be ashamed of inventing heroes who are white, villains who are black, and heroines who are a delicate shade of pink.

I am not an angry young, or even middle-aged, man. I am not “involved.” My books are not “engaged.” I have no message for suffering humanity and, though I was bullied at school and lost my virginity like so many of us used to do in the old days, I have never been tempted to foist these and other harrowing personal experiences on the public. My opuscula do not aim at changing people or making them go out and do something. They are written for warm-blooded heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes and beds.

I am not an angry young, or even middle-aged, man. I am not “involved.” My books are not “engaged.” I have no message for suffering humanity and, though I was bullied at school and lost my virginity like so many of us used to do in the old days, I have never been tempted to foist these and other harrowing personal experiences on the public. My opuscula do not aim at changing people or making them go out and do something. They are written for warm-blooded heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes and beds.

I have a charming relative who is an angry young littérateur of renown. He is maddened by the fact that more people read my books than his. Not long ago we had semi-friendly words on the subject and I tried to cool his boiling ego by saying that his artistic purpose was far, far higher than mine. He was engaged in “The Shakespeare Stakes.” The target of his books was the head and, to some extent at least, the heart. The target of my books, I said, lay somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh.

These self-deprecatory remarks did nothing to mollify him and finally, with some impatience and perhaps with something of an ironical glint in my eye, I asked him how he described himself on his passport. “I bet you call yourself an Author,” I said. He agreed, with a shade of reluctance, perhaps because he scented sarcasm on the way. “Just so,” I said. “Well, I describe myself as a Writer. There are authors and artists, and then again there are writers and painters.”

This rather spiteful jibe, which forced him, most unwillingly, into the ranks of the Establishment, whilst stealing for myself the halo of a simple craftsman of the people, made the angry young man angrier than ever and I don’t now see him as often as I used to. But the point I wish to make is that if you decide to become a professional writer, you must, broadly speaking, decide whether you wish to write for fame, for pleasure or for money. I write, unashamedly, for pleasure and money.

I also feel that, while thrillers may not be Literature with a capital L, it is possible to write what I can best describe as “Thrillers designed to be read as literature,” the practitioners of which have included such as Edgar Allan Poe, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Eric Ambler and Graham Greene. I see nothing shameful in aiming as high as these.

All right then, so we have decided to write for money and to aim at certain standards in our writing. These standards will include an unmannered prose style, unexceptional grammar and a certain integrity in our narrative.

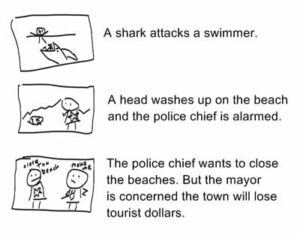

But these qualities will not make a best seller. There is only one recipe for a best seller and it is a very simple one. You have to get the reader to turn over the page.

If you look back on the best sellers you have read, you will find that they all have this quality. You simply have to turn over the page.

Nothing must be allowed to interfere with this essential dynamic of the thriller. This is why I said that your prose must be simple and unmannered. You cannot linger too long over descriptive passages.

There must be no complications in names, relationships, journeys or geographical settings to confuse or irritate the reader. He must never ask himself “Where am I? Who is this person? What the hell are they all doing?” Above all there must never be those maddening recaps where the hero maunders about his unhappy fate, goes over in his mind a list of suspects, or reflects what he might have done or what he proposes to do next. By all means, set the scene or enumerate the heroine’s measurements as lovingly as you wish, but in doing so, each word must tell, and interest or titillate the reader before the action hurries on.

I confess that I often sin grievously in this respect. I am excited by the poetry of things and places, and the pace of my stories sometimes suffers while I take the reader by the throat and stuff him with great gobbets of what I consider should interest him, at the same time shaking him and shouting, “Like this, damn you!” about something that has caught my particular fancy. But this is a sad lapse, and I must confess that in one of my books, Goldfinger, three whole chapters were devoted to a single game of golf.

Well, having achieved a workmanlike style and the all-essential pace of narrative, what are we to put in the book—what are the ingredients of a thriller?

Briefly, the ingredients are anything that will thrill any of the human senses—absolutely anything.

In this department, my contribution to the art of thriller-writing has been to attempt the total stimulation of the reader all the way through, even to his taste buds. For instance, I have never understood why people in books have to eat such sketchy and indifferent meals. English heroes seem to live on cups of tea and glasses of beer, and when they do get a square meal we never hear what it consists of.

Personally, I am not a gourmet and I abhor food-and-winemanship. My favorite food is scrambled eggs. In the original typescript of Live and Let Die, James Bond consumed scrambled eggs so often that a perceptive proof-reader suggested that this rigid pattern of life must be becoming a security risk for Bond. If he was being followed, his tail would only have to go into restaurants and say “Was there a man here eating scrambled eggs?” to know whether he was on the right track or not. So I had to go through the book changing the menus.

Personally, I am not a gourmet and I abhor food-and-winemanship. My favorite food is scrambled eggs. In the original typescript of Live and Let Die, James Bond consumed scrambled eggs so often that a perceptive proof-reader suggested that this rigid pattern of life must be becoming a security risk for Bond. If he was being followed, his tail would only have to go into restaurants and say “Was there a man here eating scrambled eggs?” to know whether he was on the right track or not. So I had to go through the book changing the menus.

It must surely be more stimulating to the reader’s senses if, instead of writing “He made a hurried meal off the Plat du Jour—excellent cottage pie and vegetables, followed by home-made trifle” (I think this is a fair English menu without burlesque) you write “Being instinctively mistrustful of all Plats du Jour, he ordered four fried eggs cooked on both sides, hot buttered toast and a large cup of black coffee.” No difference in price here, but the following points should be noted: firstly, we all prefer breakfast foods to the sort of food one usually gets at luncheon and dinner; secondly, this is an independent character who knows what he wants and gets it; thirdly, four fried eggs has the sound of a real man’s meal and, in our imagination, a large cup of black coffee sits well on our taste buds after the rich, buttery sound of the fried eggs and the hot buttered toast.

What I aim at is a certain disciplined exoticism. I have not re-read any of my books to see if this stands up to close examination, but I think you will find that the sun is always shining in my books—a state of affairs which minutely lifts the spirit of the English reader—that most of the settings of my books are in themselves interesting and pleasurable, taking the reader to exciting places around the world, and that, in general, a strong hedonistic streak is always there to offset the grimmer side of Bond’s adventures. This, so to speak, “pleasures” the reader . . .

At this stage let me pause for a moment and assure you that, while all this sounds devilish crafty, it has only been by endeavoring to analyze the success of my books for the purpose of this essay that I have come to these conclusions. In fact, I write about what pleases and stimulates me.

My plots are fantastic, while being often based upon truth. They go wildly beyond the probable but not, I think, beyond the possible. . . . Even so, they would stick in the gullet of the reader and make him throw the book angrily aside—for a reader particularly hates feeling he is being hoaxed—but for two further technical devices, if you like to call them that.

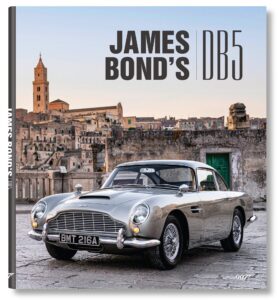

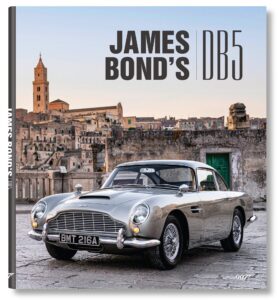

First of all, the aforesaid speed of the narrative, which hustles the reader quickly beyond each danger point of mockery and, secondly, the constant use of familiar household names and objects which reassure him that he and the writer have still got their feet on the ground. This is where the real names of things come in useful. A Ronson lighter, a 4.5 litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers supercharger (please note the solid exactitude), the Ritz Hotel in London, the 21 Club in New York, the exact names of flora and fauna, even James Bond’s Sea Island cotton shirts with short sleeves. All these details are points de repère to comfort and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure.

First of all, the aforesaid speed of the narrative, which hustles the reader quickly beyond each danger point of mockery and, secondly, the constant use of familiar household names and objects which reassure him that he and the writer have still got their feet on the ground. This is where the real names of things come in useful. A Ronson lighter, a 4.5 litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers supercharger (please note the solid exactitude), the Ritz Hotel in London, the 21 Club in New York, the exact names of flora and fauna, even James Bond’s Sea Island cotton shirts with short sleeves. All these details are points de repère to comfort and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure.

Well, I seem to be getting on very well with picking my books to pieces, so we might as well pick still deeper. People often ask me, “How do you manage to think of that? What an extraordinary (or sometimes extraordinarily dirty) mind you must have.”

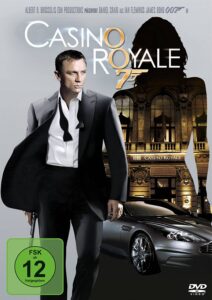

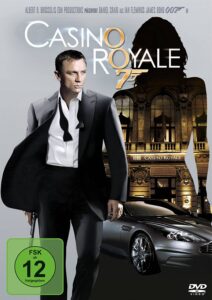

I certainly have got vivid powers of imagination, but I don’t think there is anything very odd about that. We are all fed fairy stories and adventure stories and ghost stories for the first 20 years of our lives, and the only difference between me and perhaps you is that my imagination earns me money. But, to revert to my first book, Casino Royale, there are strong incidents in the book which are all based on fact. I extracted them from my wartime memories of the Naval Intelligence Division of the Admiralty, dolled them up, attached a hero, a villain and a heroine, and there was the book.

The first was the attempt on Bond’s life outside the Hotel Splendide. SMERSH had given two Bulgarian assassins box camera cases to hang over their shoulders. One was of red leather and the other one blue. SMERSH told the Bulgarians that the red one contained a bomb and the blue one a powerful smoke screen, under cover of which they could escape.

One was to throw the red bomb and the other was then to press the button on the blue case. But the Bulgars mistrusted the plan and decided to press the button on the blue case and envelop themselves in the smoke screen before throwing the bomb. In fact, the blue case also contained a bomb powerful enough to blow both the Bulgars to fragments and remove all evidence which might point to SMERSH.

Farfetched, you might say. In fact, this was the method used in the Russian attempt on Von Papen’s life in Ankara in the middle of the war. On that occasion the assassins were also Bulgarians and they were blown to nothing while Von Papen and his wife, walking from their house to the embassy; were only bruised by the blast.

As to the gambling scene, this grew in my mind from the following incident. I and my chief, the Director of Naval Intelligence—Admiral Godfrey—in plain clothes, were flying to Washington in 1941 for secret talks with the American Office of Naval Intelligence, before America came into the war. Our seaplane touched down at Lisbon for an overnight stop, and our Intelligence people told us how Lisbon was crawling with German secret agents. The chief of these and his two assistants gambled every night in the casino at the neighboring Estoril. I suggested to the DNI that he and I should have a look at these people. We went, and there were the three men, playing at the high chemin de fer table. Then the feverish idea came to me that I would sit down and gamble against these men and defeat them, thereby reducing the funds of the German Secret Service.

As to the gambling scene, this grew in my mind from the following incident. I and my chief, the Director of Naval Intelligence—Admiral Godfrey—in plain clothes, were flying to Washington in 1941 for secret talks with the American Office of Naval Intelligence, before America came into the war. Our seaplane touched down at Lisbon for an overnight stop, and our Intelligence people told us how Lisbon was crawling with German secret agents. The chief of these and his two assistants gambled every night in the casino at the neighboring Estoril. I suggested to the DNI that he and I should have a look at these people. We went, and there were the three men, playing at the high chemin de fer table. Then the feverish idea came to me that I would sit down and gamble against these men and defeat them, thereby reducing the funds of the German Secret Service.

It was a foolhardy plan which would have needed a golden streak of luck. I had £50 in travel money. The chief German agent had run a bank three times. I bancoed it and lost. I suivied and lost again, and suivied a third time and was cleaned out, a humiliating experience which added to the sinews of war of the German Secret Service and reduced me sharply in my chief’s estimation.

It was this true incident which is the kernel of Bond’s great gamble against Le Chiffre.

Finally, the torture scene. What I described in Casino Royale was a greatly watered-down version of a French-Moroccan torture known as passer á la mandoline, which was practiced on several of our agents during the war.

So you see the line between fact and fantasy is a very narrow one. I think I could trace most of the central incidents in my books to some real happenings.

We thus come to the final and supreme hurdle in the writing of a thriller. You must know thrilling things before you can write about them. Imagination alone isn’t enough, but stories you hear from friends or read in the papers can be built up by a fertile imagination and a certain amount of research and documentation into incidents that will also ring true in fiction.

Having assimilated all this encouraging advice, your heart will nevertheless quail at the physical effort involved in writing even a thriller. I warmly sympathize with you. I too, am lazy. My heart sinks when I contemplate the two or three hundred virgin sheets of foolscap I have to besmirch with more or less well-chosen words in order to produce a 60,000 word book.

Ian Fleming’s Goldeneye House, Jamaica

In my case, one of the first essentials is to create a vacuum in my life which can only be satisfactorily filled by some form of creative work, whether it be writing, painting, sculpting, composing or just building a boat. I am fortunate in this respect. I built a small house on the north shore of Jamaica in 1946 and arranged my life so I could spend at least two months of the winter there. For the first six years I had plenty to do during these months exploring Jamaica, coping with staff and getting to know the locals, and minutely examining the underwater terrain within my reef.

But by the sixth year I had exhausted all these possibilities, and I was about to get married – a prospect which filled me with terror and mental fidget. To give my idle hands something to do, and as an antibody to my qualms about the marriage state after 43 years as a bachelor, I decided one day to damned well sit down and write a book. The therapy was successful. And while I still do a certain amount of writing in the midst of my London Life, it is on my annual visits to Jamaica that all my books have been written.

But, failing a hideaway such as I possess, I can recommend hotel bedrooms as far removed from your usual “life” as possible. Your anonymity in these drab surroundings and your lack of friends and distractions in the strange locale will create a vacuum which should force you into a writing mood and, if your pocket is shallow, into a mood which will also make you write fast and with application.

So far as the physical act of writing is concerned, the method I have devised is this. I do it all on the typewriter, using six fingers. The act of typing is far less exhausting than the act of writing, and you end up with a more or less clean manuscript. The next essential is to keep strictly to a routine—and I mean strictly. I write for about three hours in the morning—from about 9:30 till 12:30—and I do another hour’s work between 6 and 7 in the evening. At the end of this I reward myself by numbering the pages and putting them away in a spring-back folder. The whole of this four hours of daily work is devoted to writing narrative.

So far as the physical act of writing is concerned, the method I have devised is this. I do it all on the typewriter, using six fingers. The act of typing is far less exhausting than the act of writing, and you end up with a more or less clean manuscript. The next essential is to keep strictly to a routine—and I mean strictly. I write for about three hours in the morning—from about 9:30 till 12:30—and I do another hour’s work between 6 and 7 in the evening. At the end of this I reward myself by numbering the pages and putting them away in a spring-back folder. The whole of this four hours of daily work is devoted to writing narrative.

I never correct anything and I never go back to what I have written, except to the foot of the last page to see where I have got to. If you once look back, you are lost. How could you have written this drivel? How could you have used “terrible” six times on one page? And so forth. If you interrupt the writing of fast narrative with too much introspection and self-criticism, you will be lucky if you write 500 words a day and you will be disgusted with them into the bargain.

By following my formula, you write 2,000 words a day and you aren’t disgusted with them until the book is finished, which will be, and is, in my case, in about six weeks.

I don’t even pause from writing to choose the right word or to verify spelling or a fact. All this can be done when your book is finished.

When my book is finished I spend about a week going through it and correcting the most glaring errors and rewriting passages. I then have it properly typed with chapter headings and all the rest of the trimmings. I then go through it again, have the worst pages retyped and send it off to my publisher.

They are a sharp-eyed bunch at Jonathan Cape and, apart from commenting on the book as a whole, they make detailed suggestions which I either embody or discard. Then the final typescript goes to the printer and in due course the galley or page proofs are there and you can go over them with a fresh eye. Then the book is published and you start getting letters from people saying that Vent Vert is made by Balmain and not by Dior, that the Orient Express has vacuum and not hydraulic brakes, and that you have mousseline sauce and not Béarnaise with asparagus.

Such mistakes are really nobody’s fault except the author’s, and they make him blush furiously when he sees them in print. But the majority of the public does not mind them or, worse, does not even notice them, and it is a salutary dig at the author’s vanity to realize how quickly the reader’s eye skips across the words which it has taken him so many months to try to arrange in the right sequence.

Such mistakes are really nobody’s fault except the author’s, and they make him blush furiously when he sees them in print. But the majority of the public does not mind them or, worse, does not even notice them, and it is a salutary dig at the author’s vanity to realize how quickly the reader’s eye skips across the words which it has taken him so many months to try to arrange in the right sequence.

But what, after all these labors, are the rewards of writing and, in my case, of writing thrillers?

First of all, they are financial. You don’t make a great deal of money from royalties and translation rights and so forth and, unless you are very industrious and successful, you could only just about live on these profits, but if you sell the serial rights and the film rights, you do very well.

Above all, being a comparatively successful writer is a good life. You don’t have to work at it all the time and you carry your office around in your head. And you are far more aware of the world around you.

Writing makes you more alive to your surroundings and, since the main ingredient of living, though you might not think so to look at most human beings, is to be alive, this is quite a worthwhile by-product of writing, even if you only write thrillers, whose heroes are white, the villains black, and the heroines a delicate shade of pink.”

— — —

My takeaways? Too many to mention. Over to you Kill Zoners. What’d you get from this essay? And what’s the best thriller writing advice you’ve ever received (or could give, for that matter)?

— — —

Garry Rodgers has never met a spy. (Not that he knows of.) In fact, he’s never met anyone all that thrilling except, of course, his wife Rita. But Garry has had a few thrilling adventures during his three decades as a homicide detective and coroner. He’s no stranger to baggin’ the bodies.

Garry Rodgers has never met a spy. (Not that he knows of.) In fact, he’s never met anyone all that thrilling except, of course, his wife Rita. But Garry has had a few thrilling adventures during his three decades as a homicide detective and coroner. He’s no stranger to baggin’ the bodies.

Now in mid-stride, Garry Rodgers reinvented himself as a crime writer who’s creating an upcoming series titled City Of Danger. It’s a different (but not too different) new take on old hardboiled detective fiction he’s writing in net-streaming style. Garry also hosts a popular blog at DyingWords.net and psychopathically tweets on Twitter. Check him out.

Happy Independence Day to you all! Today I shall be grilling a couple of bone-in ribeyes while sipping a cool 805, a California blonde ale (I mean, what Los Angeles noir writer can resist a blonde ale?)

Happy Independence Day to you all! Today I shall be grilling a couple of bone-in ribeyes while sipping a cool 805, a California blonde ale (I mean, what Los Angeles noir writer can resist a blonde ale?)

I am not an angry young, or even middle-aged, man. I am not “involved.” My books are not “engaged.” I have no message for suffering humanity and, though I was bullied at school and lost my virginity like so many of us used to do in the old days, I have never been tempted to foist these and other harrowing personal experiences on the public. My opuscula do not aim at changing people or making them go out and do something. They are written for warm-blooded heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes and beds.

I am not an angry young, or even middle-aged, man. I am not “involved.” My books are not “engaged.” I have no message for suffering humanity and, though I was bullied at school and lost my virginity like so many of us used to do in the old days, I have never been tempted to foist these and other harrowing personal experiences on the public. My opuscula do not aim at changing people or making them go out and do something. They are written for warm-blooded heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes and beds.

Personally, I am not a gourmet and I abhor food-and-winemanship. My favorite food is scrambled eggs. In the original typescript of Live and Let Die, James Bond consumed scrambled eggs so often that a perceptive proof-reader suggested that this rigid pattern of life must be becoming a security risk for Bond. If he was being followed, his tail would only have to go into restaurants and say “Was there a man here eating scrambled eggs?” to know whether he was on the right track or not. So I had to go through the book changing the menus.

Personally, I am not a gourmet and I abhor food-and-winemanship. My favorite food is scrambled eggs. In the original typescript of Live and Let Die, James Bond consumed scrambled eggs so often that a perceptive proof-reader suggested that this rigid pattern of life must be becoming a security risk for Bond. If he was being followed, his tail would only have to go into restaurants and say “Was there a man here eating scrambled eggs?” to know whether he was on the right track or not. So I had to go through the book changing the menus. First of all, the aforesaid speed of the narrative, which hustles the reader quickly beyond each danger point of mockery and, secondly, the constant use of familiar household names and objects which reassure him that he and the writer have still got their feet on the ground. This is where the real names of things come in useful. A Ronson lighter, a 4.5 litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers supercharger (please note the solid exactitude), the Ritz Hotel in London, the 21 Club in New York, the exact names of flora and fauna, even James Bond’s Sea Island cotton shirts with short sleeves. All these details are points de repère to comfort and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure.

First of all, the aforesaid speed of the narrative, which hustles the reader quickly beyond each danger point of mockery and, secondly, the constant use of familiar household names and objects which reassure him that he and the writer have still got their feet on the ground. This is where the real names of things come in useful. A Ronson lighter, a 4.5 litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers supercharger (please note the solid exactitude), the Ritz Hotel in London, the 21 Club in New York, the exact names of flora and fauna, even James Bond’s Sea Island cotton shirts with short sleeves. All these details are points de repère to comfort and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure. As to the gambling scene, this grew in my mind from the following incident. I and my chief, the Director of Naval Intelligence—Admiral Godfrey—in plain clothes, were flying to Washington in 1941 for secret talks with the American Office of Naval Intelligence, before America came into the war. Our seaplane touched down at Lisbon for an overnight stop, and our Intelligence people told us how Lisbon was crawling with German secret agents. The chief of these and his two assistants gambled every night in the casino at the neighboring Estoril. I suggested to the DNI that he and I should have a look at these people. We went, and there were the three men, playing at the high chemin de fer table. Then the feverish idea came to me that I would sit down and gamble against these men and defeat them, thereby reducing the funds of the German Secret Service.

As to the gambling scene, this grew in my mind from the following incident. I and my chief, the Director of Naval Intelligence—Admiral Godfrey—in plain clothes, were flying to Washington in 1941 for secret talks with the American Office of Naval Intelligence, before America came into the war. Our seaplane touched down at Lisbon for an overnight stop, and our Intelligence people told us how Lisbon was crawling with German secret agents. The chief of these and his two assistants gambled every night in the casino at the neighboring Estoril. I suggested to the DNI that he and I should have a look at these people. We went, and there were the three men, playing at the high chemin de fer table. Then the feverish idea came to me that I would sit down and gamble against these men and defeat them, thereby reducing the funds of the German Secret Service.

So far as the physical act of writing is concerned, the method I have devised is this. I do it all on the typewriter, using six fingers. The act of typing is far less exhausting than the act of writing, and you end up with a more or less clean manuscript. The next essential is to keep strictly to a routine—and I mean strictly. I write for about three hours in the morning—from about 9:30 till 12:30—and I do another hour’s work between 6 and 7 in the evening. At the end of this I reward myself by numbering the pages and putting them away in a spring-back folder. The whole of this four hours of daily work is devoted to writing narrative.

So far as the physical act of writing is concerned, the method I have devised is this. I do it all on the typewriter, using six fingers. The act of typing is far less exhausting than the act of writing, and you end up with a more or less clean manuscript. The next essential is to keep strictly to a routine—and I mean strictly. I write for about three hours in the morning—from about 9:30 till 12:30—and I do another hour’s work between 6 and 7 in the evening. At the end of this I reward myself by numbering the pages and putting them away in a spring-back folder. The whole of this four hours of daily work is devoted to writing narrative. Such mistakes are really nobody’s fault except the author’s, and they make him blush furiously when he sees them in print. But the majority of the public does not mind them or, worse, does not even notice them, and it is a salutary dig at the author’s vanity to realize how quickly the reader’s eye skips across the words which it has taken him so many months to try to arrange in the right sequence.

Such mistakes are really nobody’s fault except the author’s, and they make him blush furiously when he sees them in print. But the majority of the public does not mind them or, worse, does not even notice them, and it is a salutary dig at the author’s vanity to realize how quickly the reader’s eye skips across the words which it has taken him so many months to try to arrange in the right sequence. Garry Rodgers has never met a spy. (Not that he knows of.) In fact, he’s never met anyone all that thrilling except, of course, his wife Rita. But Garry has had a few thrilling adventures during his three decades as a homicide detective and coroner. He’s no stranger to baggin’ the bodies.

Garry Rodgers has never met a spy. (Not that he knows of.) In fact, he’s never met anyone all that thrilling except, of course, his wife Rita. But Garry has had a few thrilling adventures during his three decades as a homicide detective and coroner. He’s no stranger to baggin’ the bodies. Your regularly scheduled blog post will begin following this moment of shameless self promotion. Yesterday was Launch Day for

Your regularly scheduled blog post will begin following this moment of shameless self promotion. Yesterday was Launch Day for

But it’s not as simple as that, is it? Persistence can be grueling at times.

But it’s not as simple as that, is it? Persistence can be grueling at times.