By PJ Parrish

I dunno, maybe this is going to sound simplistic to most of you, but I’m going to throw it out there anyway: What should go into a chapter?

I’ve been thinking about this since last week after reading Jordan’s excellent post on narrative drive. In the comments section, BK Jackson wrote this:

The one of these I fumble with the most is having a goal for every scene. Sure, it’s easy when they’re about to confront the killer or it’s about a major plot point or a clue, but what about scenes that just set the stage of story-world and its people? Sure, you don’t want mundane daily life stuff, but sometimes I write scenes of protag interacting with someone in story world and, while I can’t articulate a specific goal for the scene, it seems cold and impersonal to leave it out.

And Marilynn wrote:

Working with newer writing students, I’ve discovered that some write a scene…because they are trying to clarify the ideas for themselves, not for the reader.

I’ve found writers often struggle with this. It’s as if they just start writing, trying to figure out what the heck is happening, then they just run out of gas. End of chapter. But that’s not how it should go. No, you don’t need to outline, but you really need to stop and ask yourself questions before you write one word: How do you divide up your story into chapters? Where do you break them? How long should each chapter be? How many chapters long should your book be? And maybe the hardest thing to figure out: What is the purpose of each chapter? Or as BK put it, what is the “goal?”

Again, this sounds simplistic but it’s not simple. How you CHOSE to divide up your story affects your reader’s level of engagement. The way you CHOSE to chop up your plot-meat helps the reader digest it. The way you CHOSE to parcel out character traits helps your reader bond with people. And the way you CHOSE to manipulate your story via chapter division enhances — or destroys — their enjoyment.

For some writers, this comes naturally, like having an ear in music. But for many of us, it is a skill that can be learned and perfected. So let’s give it a go.

First, do we even need chapters? Marilynne Robinson doesn’t use them. James Dickey’s To The White Sea is one big tone-poem. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road uses a couple dots instead of chapter headings, perhaps to emphasize the in media res feeling of a long journey. (I was so pulled into that book I didn’t even notice it didn’t have chapters!) But most of us mere mortals probably need to break things up a bit.

Why? Chapters give your reader a mental respite. Chapter breaks allow the reader to digest everything that’s happened. They also help build suspense for what is yet to come. If you divide them up artfully instead of willy-nilly.

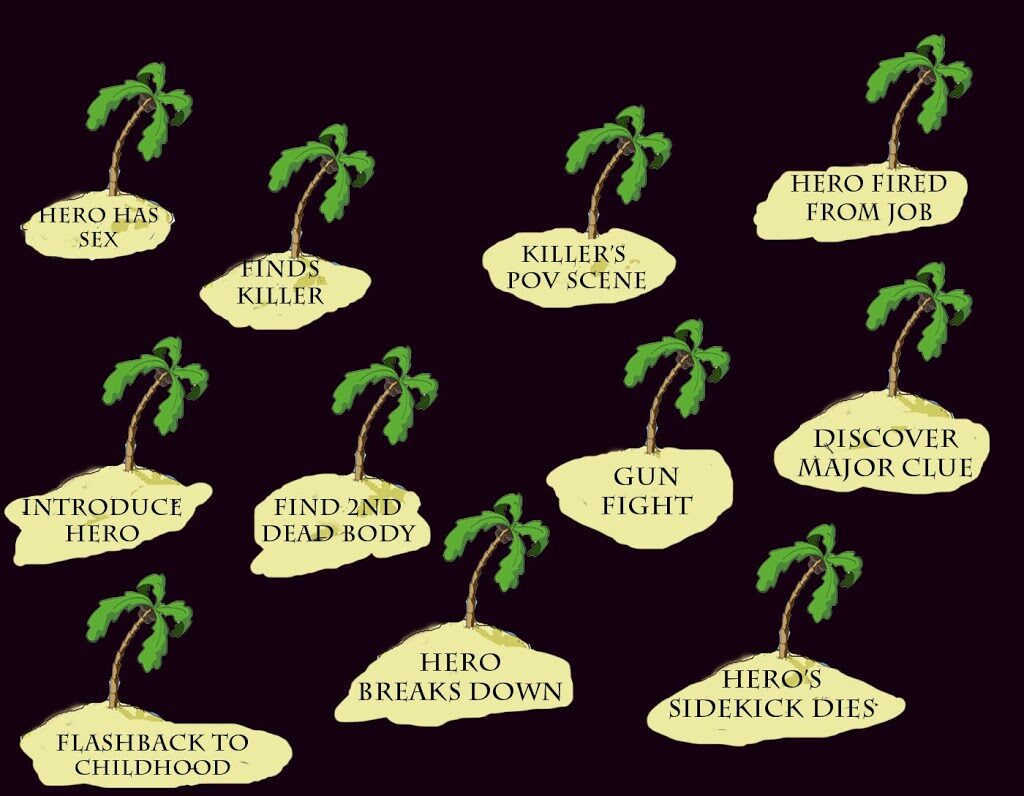

Maybe it’s helpful to think of each chapter as a dramatic island. (I wrote a whole blog about this a couple years back). Then build bridges (transitions) between them. Or think of each chapter as a mini short-story. Each chapter, ideally, has its own dramatic arc — a beginning to pull the reader in, a middle with meat, and a kicker ending that makes the reader want to turn the page.

Maybe it’s helpful to think of each chapter as a dramatic island. (I wrote a whole blog about this a couple years back). Then build bridges (transitions) between them. Or think of each chapter as a mini short-story. Each chapter, ideally, has its own dramatic arc — a beginning to pull the reader in, a middle with meat, and a kicker ending that makes the reader want to turn the page.

But first, ask yourself this about each chapter: What do I want to accomplish?

The first chapter is sometimes the easiest. We talk about this all the time here, especially in our First Page Critiques. To review: For crime fiction (if not all good fiction, in my humble opinion) an opening chapter should establish time and place, introduce a major character (often the protagonist or villain), set the tone, and at least hint at some disturbance in the norm. (A body has been found, a gauntlet thrown, a character called to action). Yeah, we get all that, right?

But, as BK said, things tend to fall apart after that. The deeper you get into your story, the harder it becomes to articulate what needs to happen within each chapter. For those of you who outline, maybe it’s easier. But I’ve seen even hardcore outliners lose their way. When you sit down to write, sometimes, it just pours out in this giant amorphic blob, until, exhausted, you just quit writing. End of chapter? No, end of energy because you didn’t pace yourself.

So, before you start a chapter, STOP. Sit there and think, really hard, until blood beads on your forehead. Don’t write a word until you can answer this question:

What do I need to accomplish in this chapter?

Some other things to help you home in on chapter “goals.”

Write a two-line summary before you start each chapter. For a revenge plot, you might write “In this chapter the reader will find out villain’s motivation for killing his brother.” Or in a police procedural you might write: “In this chapter, Louis and Joe put together the clues and realize Frank isn’t the killer.”

Look for ways for every chapter work harder, to have secondary purposes. Main purpose: “In chapter four, Louis goes to the UP to find evidence on the cold case of the dead orphan boys.” But also in that chapter: “The reader gets some background on Louis’s years in foster care.” (character development plus resonates with lost boy theme) Also: “Add in good description of the Upper Peninsula.” (Establishes sense of place and underscores desolate mood.”)

Maybe this is what BK was asking for — how to make those later chapters more muscular. As you go deeper into your plot, keep looking for layers you can add, ways to make each chapter have secondary “goals.”

Use physical tools. Don’t visualize your book as a continuous unbroken roll. Think of it as a lot of little story units you can move around. Think Lego blocks, not toilet paper. Some writers draw elaborate story boards. I’m told there is software for this, but Kelly and I are Luddites. We write the salient points of each chapter on Post-It notes that we color code for POVs and move them around on a big poster board. Vladimir Nabokov wrote chapter notes on index cards and shuffled them until he found a chapter sequence that made sense.

How do you keep your chapters from just petering out? Again, you have to THINK about this before you write. Here’s another tip: Look for logical breaks in your narrative for your endings. Such as:

- Change of place. Say, you move from New York City to London

- Change in point of view. From maybe your protagonist to the bad guy.

- Change in time. (a couple hours or a couple years depending on your story)

- Change in dramatic intensity. Say you just wrapped up a big mano-a-mano fight. The next thing that happens is having your hero recovering and thinking about what just happened. That might be a great place to start a new chapter. It goes to pacing: Follow up an intense action scene chapter with a slower chapter that allows the reader to catch their breath.

By the end of each chapter, you should resolve at least one thing. A car chase ends. A victim dies. Two cops figure out a major clue and decide to act. One character tells another something important about their background. When you end a chapter, you want to send your reader a clear signal that what they just read is important. One trick I love: End a chapter just before the climax of a significant story arc: This is a classic trick of the thriller and mystery novel. You lead your reader right up to the edge of a tense moment then you end the chapter. They have no choice but to turn the page!

I wish I could remember who said this: A good chapter ending does two things — it closes one door and it opens another one.

Whew. Enough already, you’re saying. I hear you. Okay, let’s move on to some easier stuff.

How long should your chapters be? I wrote a whole blog on this a while back, but if you don’t want to go back and read it, here’s the short answer: As long as each chapter needs to be.

It’s a matter of style — your style. But, if you are following the idea of a dramatic arc for each chapter-island, the answer should come organically. As you move through your story, you might want to try for a consistency in length — be it 200 words or 2000 words. Why? I think it helps your reader get a sense of your style and pacing. But don’t sweat this too much. If you are moving along at a steady pace of say 1500 words per chapter and suddenly one comes out at 5000 words, you might want to go back in and look for a logical break in your narrative or action. You might find, with judicious rewriting, that you’ve really got two tight chapters instead of one long one.

Okay, I’m running long again. One more question:

Should you use chapter titles? Lots of writers love these, especially fantasy and YA writers. I’m on the fence about them. I’ve never used them, but for one complex book, we did have three “books” that had titles. When chapter titles are witty, they can be great because they provide hints about what to expect within the chapter. But if they are mundane or obvious, they are just annoying and pretentious.

One story I heard was that before the release of one of her Harry Potter books, JK Rowlings refused to divulge any plot points. But she released three chapter titles — “Spinners End,” “Draco’s Detour,” and “Felix Felicis” — just to tease readers.

Here’s some of my favorite chapter titles:

“Down the Rabbit-Hole.” Chapter 1, Alice in Wonderland. So great it has become a modern metaphor, especially in politics.

“I Begin Life On My Own Account, And Don’t Like It.” Chapter 11, David Copperfield. Didn’t realize Dickens had a sense of humor.

Rick Riordan might be the chapter title king. Here are six from just one novel:

“I Accidently Vaporize My Pre-Algebra Teacher”

“I Play Pinochle with a Horse”

“I Become Supreme Lord of the Bathroom”

“We Get Advice from a Poodle”

“A God Buys Us Cheeseburgers”

“I Battle My Jerk Relative”

But here’s my all-time favorite from Ian Fleming’s Live And Let Die, chapter 14:

“He disagreed with something that ate him.”

And that is a good place to end.

“Plot Points! Waitress, I need three more plot points.”

Such good advice, as always. I’ll be rereading this at the eye clinic where the Hubster is having is 2nd cataract surgery. More useful (and interesting) than this month’s book club choice. 🙂

Or last year’s issue of O Magazine…. 🙂

Robert McKee talks about “story values.” These values are thing like love/hate, confusion/understanding, courage/fear, honesty/deception, calm/storm, etc. etc.

He argues, correctly I think, that at least one story value should change from the start of a scene to the end of a scene, otherwise there is no point to that scene. I try to keep this in mind, if not before I write a chapter, then certainly before I consider the chapter done.

I like that idea, Ed. As I was writing this post, I had it in the back of my mind that we have covered this topic many times here (notably by James in his posts about structure). But sometimes, if someone says the same thing in a different way, it resonates with someone. Which is why I like your “point of view.” It adds to the knowledge stew.

Legos vs toilet paper, haha! Okay, I laughed, but it’s a really helpful image, so are the islands.

I tried hard to improve on the toilet paper metaphor but came up short. I thought of saying a player piano roll but was afraid no one was old enough to get it. 🙂 I kept seeing my little dog who likes to go into the bathroom and furiously unravel the toilet paper roll until it is a big pile of mess on the floor. What is his point? Fun, I guess. But the pile of TP is also an apt image for writing out of control.

I think the idea of “chapters” is dated. I’ve always thought in “scenes” which, as noted by Kris, should be as long as they need to be. But being trained in cinema, I can have a scene that is as short as a quick “shot.”

I became enamored of the style Andrew Vacchs uses. No chapter numbers, just white space between scenes, with the first line set off by a drop cap or capped first few words. It’s freeing.

For an action scene I like to think of objective, obstacles, outcome. For reaction scenes or beats, emotion, analysis, decision.

I also like stopping a scene before it’s logically “completed.” It give forward momentum.

I, too, prefer to think in scenes, Jim. Though I’ve had no formal screenwriting training, I am constantly analyzing every movie I see for structure. But I’ve found that sometimes confuses some folks who are struggling with structure. And your last point is very well taken. A chapter or scene ending leaves something to be desired, but in a good way, imo.

Great information, PJ, and especially useful for me right now as I’m reading through the first draft of my WIP and realizing some chapters need to be moved around and some just aren’t working even though I have a reason for each one. I’m going to use your advice to “Look for ways for every chapter work harder, to have secondary purposes.”

Btw, the chapters in my first (and only) published novel are short — rarely more than 1000 words each. A number of folks have mentioned they liked the shorter chapters because they learned starting a new chapter late at night was not going to be a huge time commitment. I guess busy people read books with one eye on the page and the other on the clock! Maybe short chapters are a good way to keep ’em turning the pages.

If anyone tries to tell you your chapters MUST be a certain length, run don’t walk away. If your style is so propulsive that you can get folks to keep turning the pages, yeah, you can write chapters 3000 words long! It goes to the idea of pacing. I never think about someone reading my books in bed. If I am doing my job, I keep them up until the scene logically ends. If your narrative drive, as Jordan called it, is humming, readers don’t realize they’ve read 2000 words. (which is my average). But yeah, I agree there is something to keeping your chapters within reasonable lengths.

Thanks for pointing this out.

Forgive me if this is a really dumb question (remember, I’m new at this): Is chapter length in any way a function of genre?

No dumb questions here Kay.

I don’t really know the answer to your question. I am not well-read enough in genres other than crime fiction to even bluff an answer. I think mysteries, and to a greater degree, thrillers tend toward shorter chapters. I just Googled this and discovered Harry Potter books average out at 4,560 words per chapter! And The Hunger Games average at 3700 but broken into sections. So…who knows? I sense there is a trend toward shorter chapters in crime fiction but that is just a guess. Romance tends to average around 1000 per. But rules, as we always say here, are made to be broken. I say don’t get too hung up on formulas. Instead, find our own rhythm. Reliable beta readers can be helpful with this…you can test their patience!

This comes at a handy time for me too, PJ. As the WIP grows, my rough draft chapter breaks can either help or hinder pace. I had a reader friend remark on one of my books how well my chapter sizes (1500-2000 words) suited her reading rate. I hadn’t thought about that aspect before, but it’s something to consider, depending on genre.

Re: Kay’s chapter reorganization, I realize not everyone uses MS Word, but there’s a feature I use for that very purpose–the Navigation Pane. It’s a checkbox in the middle of the “View” menu ribbon, (also a dropdown under “Show” if your window is smallish). If you base your chapter heading style on the default “Header1”, your chapter names will appear in the left Navigation panel. You can click and drag to rearrange chapter sequences. It’s also a great way to navigate (duh) among chapters.

Dan, that’s great info about rearranging chapters in Word. Very useful!

I’m using Scrivener for my current work because of the ease of organizing things. It’s a bit of a learning curve, but I’m liking it.

I tried Scrivener, Kay, even took a short course in it but I got totally lost. At my age, I have to factor in:

Learning Curve x hours in day + days left in my life – walking dog = can’t do it.

Hahaha! Now we’re on the same page!

Your friend’s observation about your chapter sizes goes to my point that it’s a matter of finding your pace and style. I don’t think any reader pays close attention to the length of chapters but I so think readers, as they get deeper into your book, subconsciously pick up on your pacing style. It gives them a comfort level as they move through your story. Which is why, once in a great while, if you maybe toss in a shorter action scene, it can be a nice surprise.

But then there are writers like Joyce Carol Oates whose chapter lengths are all over the place — and who cares?

I don’t agree with the idea that a chapter should end at the end of an event. Sure, it works sometimes, but most of the time, it puts the reader at a dead stop and gives them an excuse to stop reading. Too many dead stops and “this is a real page-turner” won’t be part of those reviews. Find a scary pause in that fight where things are going bad for the main character, change the chapter, finish the fight and move on to the consequences of the fight and how the character must move forward to achieve his final goal, then end the chapter. If a quieter chapter answers important plot or character points, then it should end with even more important questions being asked.

My own preference on building chapters and plot is the idea of interlocking questions. Questions asked, then answered while more questions are being asked like the links in a chain. If the questions are interesting enough and the answers have consequences for the characters, then people keep turning the pages. The obligatory blog link:

https://mbyerly.blogspot.com/2011/09/interlocking-questions.html

Thanks the the link Marilynn. I like your suggestion to “think of yourself as the reader. What will the reader want to know at that moment in the narrative? What questions can you answer and what answers can be held back?”

Good fodder for the discussion.

Great breakdown, Kris!

“Write a two-line summary before you start each chapter.” Sometimes that’s all the outline I need. Doing it 2-3 chapters ahead really keeps me on track.

I’m a half-way Scrivener user. I like it for character and place sheets, plus it’s so easy to reorder scenes. BUT for whatever reason I sometimes have a hard time composing in it. In that case I’ll write in Word and paste into Scrivener, then assemble and edit for Word. Dang, that sounds complicated.

I’m a day late but thanks for the follow up to this discussion. Helpful info I can use both from post and comments.

I’m a day late in answering. Thanks for inspired the post!

Pingback: Friday Finds – Staci Troilo