Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold. — William Butler Yeats.

By PJ Parrish

Recently I did a manuscript critique for charity. This was a much longer version of what we regularly do here at TKZ with our First Page Critiques, about 30 pages. But it’s funny…some of the same issues we talk about in 400-word samples are also readily apparent in this longer sample.

But one thing really strikes me about both: Often the writer doesn’t seem to have a firm grasp on what their scene is “about.” And this is a fatal flaw that affects your plot structure and your characterizations.

I was going to do a full-throttle post on this for today when I realized (with that little nagging voice that comes with older age) that I might have covered this before. Sure enough, there in the archives was my post from October 2019: “What’s Your Point? Figuring Out What Goes Into Each Chapter.

It’s worth a revisit, I think. Back in 2019, one of our regulars here BK Jackson, posted this comment:

The one of these I fumble with the most is having a goal for every scene. Sure, it’s easy when they’re about to confront the killer or it’s about a major plot point or a clue, but what about scenes that just set the stage of story-world and its people? Sure, you don’t want mundane daily life stuff, but sometimes I write scenes of protag interacting with someone in story world and, while I can’t articulate a specific goal for the scene, it seems cold and impersonal to leave it out.

And Marilynn added:

Working with newer writing students, I’ve discovered that some write a scene…because they are trying to clarify the ideas for themselves, not for the reader.

This is exactly what was going on with my recent critique. The writer offered three completed chapters. In Chapter 1, he seemed to have a good grasp of where he was going: A man (I’ll call him Dan) returns to his small hometown of Tomales, California on a visit but learns about the mysterious death of a college friend. Interweaving personal revelations about his family is this possible murder and Dan begins to feel compelled to investigate. Good! Amateur sleuth sub-genre. A mysterious murder. Family secrets mixed in. Nice start.

But then came chapter two. It flashbacks 20 years prior (with a time tagline to alert us) and we get the 18-year-old version of Dan who, on scholarship, is entering Stanford University, where he feels inferior. The only action in this chapter seems to be when a roommate drags him to a cigar-frat party, telling him he needs to better himself so he can get in with “the right people.” (The title of the book). Dan, in his cheap suit and bad haircut, feels out of place among the swells and the beautiful coeds. The chapter ends with him yearning to be in this fancy world.

Chapter 3 goes back to the present. Dan, now a lawyer with a family, meets his old friend (and four other men in their circle from Stanford) for drinks. As the alcohol flows, the past (and Dan’s jealousy and inferiority complex) flairs anew. Dan tries to bring up with the death of the college friend (a shy kid who the others knew but was not part of their group) and everyone cuts him off. Most of the chapter is backstory on each of the men in the frat circle — how successful they are now. Dan leaves the bar and meets his wife for dinner. The end of the chapter is Dan thinking that someone in his old cigar group knows something about the murder and he thinks that no matter how far you get in life, you’re just an older version of your young insecure self.

That’s it.

Now, there was some good writing in the chapters. But do you see the issue? I got the feeling the writer, after the decent set up of Chapter 1, wasn’t sure where to go plot-wise. It was as if he was thinking, “Oops! I’ve hit 2000 words, I better wrap this up!” and just stopped. I told him, gently but firmly, in the critique, that he didn’t have a firm grasp of the PURPOSE OF EACH SCENE AND CHAPTER. The short synopsis that came with the submission seemed to verify this.

Now, I am a confirmed pantser. I don’t outline. But I never start writing a chapter until I have figured out exactly what I need to accomplish in each. To quote myself from my old post:

How you CHOSE to divide up your story affects your reader’s level of engagement. The way you CHOSE to chop up your plot-meat helps the reader digest it. The way you CHOSE to parcel out character traits helps your reader bond with people. And the way you CHOSE to manipulate your story via chapter division enhances — or destroys — their enjoyment.

For some writers, this comes naturally, like having an ear in music. But for many of us, it is a skill that can be learned and perfected.

No, you don’t need to outline, but you really need to stop and ask yourself questions before you write one word: How do you divide up your story into chapters? Where do you break them? How long should each chapter be? How many chapters long should your book be? And maybe the hardest thing to figure out: What is the purpose of each chapter? Or as BK put it, what is the “goal?”

The first chapter is relatively easy. To review what we talk about all the time with our First Page Critiques: An opening chapter should establish time and place, introduce a major character (often the protagonist or villain), set the tone, and set up some disturbance in the norm. (A body has been found, a gauntlet thrown, a character called to action).

But, as BK and Yeats note, things tend to fall apart after that. The deeper you get into your story, the harder it becomes to articulate what needs to happen within each chapter. For those of you who outline, maybe it’s easier. But I’ve seen even hardcore outliners lose their way. When you sit down to write, sometimes, it just pours out in this giant amorphic blob, until, exhausted, you just quit writing. End of chapter? No, end of energy because you didn’t pace yourself.

Each chapter needs a good beginning, an arc, and a satisfying ending. I don’t know if this is helpful, but as I told my critique person, I think of each chapter as an island. I figure out the “geography” of each island and then — and this is important — I build bridges between them.

Here are a few other techniques I’ve found helpful:

Write a two-line summary before you start each chapter. For a revenge plot, you might write “In this chapter the reader will find out villain’s motivation for killing his brother.” Or in a police procedural you might write: “In this chapter, Louis and Joe put together the clues and realize Frank isn’t the killer.”

Make every chapter work harder, to have secondary purposes. Main purpose: “In chapter four, Louis goes to UP and finds evidence on the cold case of the dead orphan boys.” But secondarily: “The reader gets some background on Louis’s years in foster care.” (character development plus resonates with lost boy theme) Also: “Add in good description of the Upper Peninsula.” (Establishes sense of place and underscores desolate mood.”). So I accomplished THREE goals in that chapter.

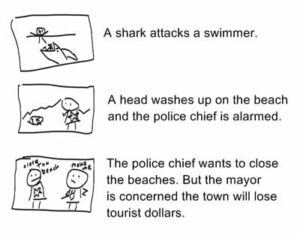

Don’t visualize your book as a continuous unbroken roll. Think of it as a lot of little story units you can move around. Think Lego blocks, not toilet paper. Some writers draw elaborate story boards, others use software. I use Post-It notes, color coded for POVs, and shuffle them around on a poster board. I love this cartoon from Jessica Hatchigan’s blog on how to storyboard your plot:

Yes, it’s that easy. 🙂

Look for logical breaks to end and begin chapters. You might change locations. Or point of view. Or there’s a change in time (hours or years depending on your story). Maybe there is just a change in dramatic intensity. Say you just wrapped up a big mano-a-mano fight. The next chapter might be your hero licking his wounds as he pours over old police files (what I call a “case chapter or info chapter.”) It goes to pacing. Not every chapter has to be wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am. Follow up an intense action scene chapter with a slower chapter that allows the reader to catch their breath. Just make sure it advances the plot!

Think resolution or big tease. As I said, every chapter has its own mini-arc that fits into the major overall arc of your story. So, in a sense, most chapters should “resolve” themselves in some way. A car chase ends. A victim dies. Two cops figure out a major clue and decide to act. One character tells another something important about their background. However: It’s also effective to stop just before the climax. You lead your reader right up to the edge of a tense moment then you end the chapter. Just make sure you deliver in the next one.

So, in summary, as I told my critique writer, you have to get the elbow grease of the brain working before you write. Every chapter needs clear goals, things you need to accomplish in it. Stop. Look. Listen to your inner voice and those of your characters. Then…write right.

Kris, this is terrific. Sometimes as writers we are so focused on the large general issues that we forget about the smaller specific ones and then wonder why our story isn’t working. I think of an automobile. A broken fan belt will shut you down just as effectively as no engine at all. The same is true of chapters.

A lot of readers don’t think in terms of pages, but of chapters. “I’ll read one more chapter and if this doesn’t pick up…” dum da dumdum. Thanks for helping us to make sure that things…pick up!

Have a great day, Kris. Thanks so much.

My writer brain organizes things in scenes and chapters. I try to have the chapters be roughly the same size (word count), but it doesn’t always work out. I average about 2000 words per chapter. If I do end up with one that is say, 4,000 words, I go back and see if it can be LOGICALLY broken in two. Usually, I can de-connect a scene and work it into its own chapter. But on rare occasion, I will let a chapter run long. No need to get anal. 🙂

Excellent advice, Kris.

I’m in the “start a new book” phase. Only 5 chapters in, and there’s been a significant hiatus while I dealt with edits, formatting, the dreaded book description, uploading for preorder, etc. Might take one more day “off” and then start re-reading the new book, and I’ll definitely be dealing with the “What is this chapter doing here?” issues. As you point out, it’s much easier to deal with this a chapter (or scene) at a time than after you’ve written 90K words.

I can’t remember if it was Donald Maass who said, “Your character has to want something in every scene, even if it’s only a drink of water.”

Ha…I recently re-read something I had rewritten a good two months ago and realized I didn’t need the scene at all. It was fine, but really didn’t advance the plot or character. Out it went.

Thanks for a great post, Kris. I can use the repetition, if there was any. I’ve been experimenting with an online narrative outline on Google Docs to plan my last two books, so I can work on it from anywhere, change it easily, and have it open while I write in Scrivener. I have subsections for each chapter, with setting, conflict, emotion, and cliffhanger. I need to add a section for purpose.

“But, as BK and Yeats note, things tend to fall apart after that.” Entropy is the measure of disorder. The second law of thermodynamics states, “All systems tend toward greater entropy.” Things fall apart. (Except humankind’s ego that we are constantly improving.)

You got me curious about “entropy.” I always thought it meant like a slow decline into chaos. Then I found this: “Entropy: a thermodynamic quantity representing the unavailability of a system’s thermal energy for conversion into mechanical work, often interpreted as the degree of disorder or randomness in the system.”

I shouldn’t have looked.

Terrific advice as always, Kris. I think it terms of scenes…sometimes I jump-cut ’em, sometimes I complete the scene. It’s good to mix things up a bit, keep a reader on their toes. 😉

Amazing post. Chapter arcs get talked about so little, but they are just as vital as understanding any other part of the craft.

I’m an outliner, but I recently came up with this formula for figuring out how many chapters to have in a book. When I find my first doorway of no return, and how long it takes me to set up the normal world, I just multiply that by four, maybe take a chapter or two away depending on where in said chapter the doorway occurs. Now I have a big empty space for the second act, but it’s broken into chapters and becomes more manageable. I’ve also discovered that the chapters in between plot points are best used for 1. paying off the previous event (consequences) and 2. setting up the next point.

Although I don’t outline, your process makes sense to me. It is comforting to have such a map. Even if you veer from it.

I write in scenes, and an action scene for me has a structure: objective, obstacles, outcome. That’s what I need to know before I write.

My current series is all scenes, no chapters ornimbers. Cinematic. Picked this up from Andrew Vachss.

So the final manuscript will have to chapter numbers?

Right. Just a break between scenes, and a drop cap.

Fantastic rundown, Kris. It’s easy to focus on scenes as the building block of fiction, but structuring chapters is key. One of my fiction writing mentors, who focused on scenes, used to say that “chapters are for managing whitespace,” which is an almost Zen koan-like way of implying what you laid out in today’s post–namely creating the arc of each chapter, which helps with the pace, the progression of the story, etc.

Love your tip to two a quick two line summary of what happens in the next chapter. Keeps it short and to the point 🙂

Your lego visualization of chapters as story units was also how another mentor of mine, who later became my editor, Mary Rosenblum, told me she conceived of a story, and thus, she could take it part, lego fashion, and reassemble it.

Thanks again for a very helpful take on structuring chapters.

Good morning, Kris. Thank you for this great information. I love your example of each chapter as an island.

I also use color-coded post-it notes for characters, clues, themes, suspects, etc. I have a three-door closet in my office, aka guest room, that represents the three acts of my WIP and it gets pretty colorful as the story goes along. (It’s also a great conversation piece when we have guests.) For some reason, the tactile nature of moving the post-it notes around is helpful.

I use Scrivener and it allows me to keep a synopsis of each chapter so I can print the outline view showing the synopses and see how the story flows.

I still have trouble understanding how the reader will react to a chapter. As you said, I sometimes write a chapter for myself rather than for the reader. (My Scrivener trash can has more than a few of these.) If I can conquer this hurdle, I think I’ll be a much better writer. Your post will surely help.

That closet door visual is priceless. Wonder what your guests might think seeing something on their closet door like:

In middle of night, serial killer hacks off head of victim and tosses it in lake outside guestroom window.

Ha! I’ll have to remember to add that post-it note if we have any guests who overstay their welcome.

Thank you, this is a keeper. I definitely have written ‘scenes in search of a plot!’

Great post, Kris! Below is the gem that smucked me right in the beezer. (What’s a beezer, anyway?)

But I never start writing a chapter until I have figured out exactly what I need to accomplish in each.

Currently tweaking a WIP for the last time (I hope), and will look over those scene and chapter goals. Thanks! 🙂

Excellent article.

Another nugget of wisdom. The viewpoint character has small goals they want to achieve in the scene/chapter and so does the author. They aren’t always the same goals. Cross-purposes can be fun or crazy making for the writer.

I teach using a three point system for each scene. A scene must have one or two plot points (information or events which move the plot forward), and one or two character points (important character information) so there’s three points total. Having these mini-goals keeps the writer on point toward the big goals of the novel.

That’s a great point, Marilynn, that the character vs author might have different goals. And your three-point system is helpful in trying to make each scene/chapter more muscular (ie, make it solve more issues or reach more goals). Pay attention out there, those struggling with this!

Yep. Like Jim (JSB) says above, I write in scenes. And every scene has:

—a Mission (goal) [including whether it’s Action or Reaction]

—an Opening Hook

—some Conflict/Obstacle/Tension(s)

—an Outcome or Closing Hook, many times a cliff-hanger

And I put all this in a block in my Scene Summary, which is on a Google Doc. Works for me.

Exactly. Each scene is a mini-book it itself with beginning middle and end.

I’m enthusiastically cheering and echoing all of this. Great post, great endorsing responses. Sometimes (back when people asked me questions about writing, like, at conferences) folks would wonder about “the most important thing to know about writing a novel.” Of course that list is long, with a solid 11-way tie for first place… but my answer was usually this (which Harold and JSB parallel above): each scene should be mission-driven. There are two contexts in play here, both in service of moving the story forward. The first is what leads up to the scene itself; and then, what happens after the scene, immediately and thereafter. Those two contexts empower the clarity of the purpose of the scene you are writing. If the writer is still trying to find their macro dramatic arc (either in their head or on paper in some form of outline or notes), this is nearly impossible to pull off.

And thus, this principles flies in the face of what too many writers claim is antithetical to the way they write. They say, “I just sit down and beging typing, it all happens organically.” The truth is, as TKZers know, the more weknow about the principles that drive what a novel work, and then apply that knowledge to the moment/scene we are writing, the more we are executing the “best practices” of the professional novelist.

Yeah to all of what you wrote. As for “I just sit down and start typing…” Maybe, but I would venture that this “organic” soul has everything mapped out in his head.

Two typos in the last paragraph… my bad. Happens when I get stoked, which I was here.

No problem. Love it when our folks get all geeked up about a topic.

I think of it this way: every scene needs to advance the story and/or develop characters. If a scene doesn’t do at least one of those things then what is it doing in your manuscript?

P. J. Parrish, I found this most helpful, esp. a two-sentence goal for each scene. Grazie.

I’m late here, but excellent advice, as always, Kris! I love your craft articles.