The polygraph, or lie detector, is a forensic investigative tool that’s used as an aid to verify the truthfulness, or isolate the deception, in a person’s statements. Polygraph examinations—properly conducted by trained professionals on competent subjects with a clear issue—are remarkably accurate, but they’re not foolproof. Yes. They’ve been known to be fooled. The question is—can you?

Polygraph examination interpretation is not admissible as evidence in court. They’re not a replacement or shortcut for a proper investigation and a thorough interview of the subject. Statistics show that the majority of people who undergo polygraph examinations are found to be truthful. Perhaps the term Lie Detector should be replaced with Truth Verifier.

In my policing career, I’ve been involved in around a hundred polygraph examinations, including getting hooked up myself for a test drive. (Turns out I’m a terrible liar—not sure how I’m gonna make out with this career as a fiction writer.) The subjects I’d had polygraphed were a mixture of suspects, witnesses, complainants, and victims. I’d say that sixty percent of the subjects were truthful, thirty percent were lying, and ten percent were inconclusive but leaning toward truthful.

It makes sense, when you think about it, that the majority are truthful because they know it will work to their advantage. I can’t think of the number of times I’ve had subjects refuse to take the test, giving excuses everywhere from “Those things are rigged to frame me” to “I heard you get testicle cancer from it”. Then, of course, there’s, “My lawyer told me not to” to which I responded, “You don’t even have a lawyer.”

Before giving you some tips on how to fool a polygraph when you’re dead-ass lying, let’s look at what the thing is and how it works.

The word “polygraph” comes from the Greek word “fecalpolugraphos” which means “to sniff-out bullshit”. (Go ahead—call me a liar). Polygraphs have been around since the 1920s and have evolved from clunky paper-reel machines with ink-pen devices to modern laptops with automated scoring systems. Clinically, the process is known as psychophysiological detection of deception.

The instruments are a computerized combination of medical devices that monitor a subject’s physiological responses to a set of questions designed to put the subject under the stress; the stress associated with deception. The involuntary bodily functions include heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, galvanic skin conduction, and perspiration.

Polygraphic theory dictates that a subject will show a stress spike in some, or all, of these functions when asked a question and forced to knowingly lie. In a criminal investigation, the examination questions are formed between the polygraphist and the subject during an extensive pre-test interview.

There are four categories of questions—all must be answered “Yes” or “No”. Three categories are control questions and one is issue questions.

Category One is where the subject conclusively knows they’re truthful:

Q — Is your name Garry Rodgers? “Yes”

Q — Are you a retired police officer? “Yes”

Q — Do you write books? “Yes”

Category Two is asking the subject ambiguous questions:

Q — Is there life after death? “Yes”

Q — Did the chicken come before the egg? “No”

Q — Are you still beating your wife? “No”

Category Three has the subject intentionally lie:

Q — Were you kidnapped by aliens? “Yes”

Q — Did you ever ride a camel? “No”

Q — Were you knighted by the Queen? “Yes”

Category Four deals with the issues:

Q — Did you murder Jimmy Hoffa? “No”

Q — Do you know who murdered Jimmy Hoffa? “No”

Q — Do you know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa’s remains? “No”

Only “Yes” or “No” answers are acceptable during a polygraph examination because the issue has to be clear in the subject’s mind. Black and White. All clarification is worked-out in the pre-test interview. The subject is never surprised by the question, but the question order is completely unknown. This creates an atmosphere of anxiety as the subject waits to hear the questions that really matter.

The biggest concern that I’ve heard from people who are asked to submit to a polygraph is “What happens if I’m nervous?”

This is expected. Anyone, police officers included, would experience anxiety when being examined. Part of a polygraphist’s skill is to build a rapport with the subject and put them at relative ease before the questioning starts. One of the reasons in building this rapport is to get the subject to volunteer information that the investigation hasn’t uncovered. I’ve seen subjects give critical facts because the right questions weren’t asked during the investigation, and I’ve seen subjects fall apart and confess before being strapped into the chair.

This is expected. Anyone, police officers included, would experience anxiety when being examined. Part of a polygraphist’s skill is to build a rapport with the subject and put them at relative ease before the questioning starts. One of the reasons in building this rapport is to get the subject to volunteer information that the investigation hasn’t uncovered. I’ve seen subjects give critical facts because the right questions weren’t asked during the investigation, and I’ve seen subjects fall apart and confess before being strapped into the chair.

The key to successful polygraph examinations is the the examiner’s skill. The polygraph is just a tool—an extension of the examiner’s mind and voice.

So—given there’s proven science and skill behind polygraphs—how can you fool one?

Like I said, given a professional examiner, a competent subject, and a clear issue, polygraph results are remarkably accurate. There are always exceptions, and here’s some tips on how to pass the graph when you’re truly a liar.

1. Prepare well in advance.

2. Research and understand the process so you won’t feel oppressed. The examiner will take every advantage of your ignorance.

3. Know the issue(s) and know what the examiner is looking for.

4. Talk to someone who has experienced a test.

5. Approach the test as an extreme job interview. Dress for the job. Arrive on time. Sober. Rested. Do not reschedule. Make a good first impression.

6. Know that you’re going to be video and audio recorded.

7. Understand the test starts right when you arrive and ends when you leave. It’s not just the time you’re hooked to the instrument.

8. Be on guard. There will be trick questions in the pre-test interview. It’s part of the process.

9. Listen carefully to what the examiner says and respond accordingly. Do not try and monopolize the conversation. The examiner is not your friend, despite how nice she comes across in the pre-test. Her job is to get to the truth. Remember—you’re dealing with a highly trained professional who intimately knows psychology and human behavior. If her exam shows you’re deceitful, she’ll go for your jugular in the post-test.

10. Recognize the relevant and irrelevant control questions. Focus on what’s relevant and do not offer more information than what’s pertinent to the issue.

11. Play dumb. Don’t try to impress the examiner that you’ve studied up. You’ll only look stupid.

12. Breathe normally. Shortness of breath naturally triggers the other body functions to accelerate and it will increase nervousness.

13. Take lots of time to answer.

14. Think of something mentally stressful when answering a control question—like the time when you were a kid and your dog was hit by the train. That will raise the ‘normal’ graph peaks.

15. Think of something calming when answering issue questions—like getting a new puppy. That will flatten stress peaks.

16. Keep your eyes open during the questions. The examiner will ask you to close them because this significantly alters your sensory awareness and puts you at a disadvantage. This is very important.

17. Bite your tongue during every question except the truthful control ones. This levels the playing field.

So, who’s got away when facing a lie detector?

I call her The Mother From Hell. I investigated a bizarre case of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy—a rare form of child abuse where a parent causes harm to their child to bring attention to themselves. This woman repeatedly complained that her infant daughter was choking, then was caught by hospital staff with her hands around the little girl’s neck. She denied it. We polygraphed her. She blew the needles off the instrument and confessed. But, The Mother From Hell got off in court because they found her confession inadmissible due to it being “elicited under oppression” from the polygraph examination and subsequent interrogation. It was a total horseshit ruling.

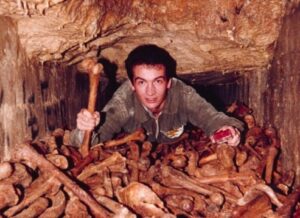

Gary Ridgway, The Green River Serial Killer from Seattle, strangled over fifty women in the 1980’s. He was on police radar early in the serial killing investigation, ‘passed’ a polygraph, and got warehoused as a suspect. He went on to kill many more before being caught on DNA.

So, can you fool the polygraph?

Maybe, but I doubt it.

The best advice I can give is, if you tell lies, don’t take a lie detector.

———

Over to you, Kill Zoners. Has anyone out there taken a polygraph examination? Would you take one? And has anyone ever used a polygraph examination scene in their books?

———

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating unexpected and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry passes himself off as a crime writer and enthusiastic indie publisher. Possibly a podcaster, too. 😉

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating unexpected and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry passes himself off as a crime writer and enthusiastic indie publisher. Possibly a podcaster, too. 😉

One of Garry Rodgers’s writing projects is a series based on true crime cases he was involved in. Investigating them, that is. Not committing the crimes. Garry lives on Vancouver Island at Canada’s west coast where he hosts a popular blog that you simply must follow at Dyingwords.net. You can also connect with him via Twitter @GarryRodgers1.

Dave Barry once said that the best time to visit Florida’s Disney World is 1965. Makes sense to me. I never saw the value in taking out a second mortgage to pack the family into a metal tube for a six-hour flight to an extended stay in a hot and humid swamp when we have Disneyland an hour away by car.

Dave Barry once said that the best time to visit Florida’s Disney World is 1965. Makes sense to me. I never saw the value in taking out a second mortgage to pack the family into a metal tube for a six-hour flight to an extended stay in a hot and humid swamp when we have Disneyland an hour away by car.

Do you have any animal characters in your WIP? Tell us about them!

Do you have any animal characters in your WIP? Tell us about them!

This is expected. Anyone, police officers included, would experience anxiety when being examined. Part of a polygraphist’s skill is to build a rapport with the subject and put them at relative ease before the questioning starts. One of the reasons in building this rapport is to get the subject to volunteer information that the investigation hasn’t uncovered. I’ve seen subjects give critical facts because the right questions weren’t asked during the investigation, and I’ve seen subjects fall apart and confess before being strapped into the chair.

This is expected. Anyone, police officers included, would experience anxiety when being examined. Part of a polygraphist’s skill is to build a rapport with the subject and put them at relative ease before the questioning starts. One of the reasons in building this rapport is to get the subject to volunteer information that the investigation hasn’t uncovered. I’ve seen subjects give critical facts because the right questions weren’t asked during the investigation, and I’ve seen subjects fall apart and confess before being strapped into the chair. Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating unexpected and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry passes himself off as a crime writer and enthusiastic indie publisher. Possibly a podcaster, too. 😉

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating unexpected and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry passes himself off as a crime writer and enthusiastic indie publisher. Possibly a podcaster, too. 😉

My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

Recently one of our regulars, RLM Cooper,

Recently one of our regulars, RLM Cooper,