The polygraph, or lie detector, is a forensic investigative tool that’s used as an aid to verify the truthfulness, or isolate the deception, in a person’s statements. Polygraph examinations—properly conducted by trained professionals on competent subjects with a clear issue—are remarkably accurate, but they’re not foolproof. Yes. They’ve been known to be fooled. The question is—can you?

Polygraph examination interpretation is not admissible as evidence in court. They’re not a replacement or shortcut for a proper investigation and a thorough interview of the subject. Statistics show that the majority of people who undergo polygraph examinations are found to be truthful. Perhaps the term Lie Detector should be replaced with Truth Verifier.

In my policing career, I’ve been involved in around a hundred polygraph examinations, including getting hooked up myself for a test drive. (Turns out I’m a terrible liar—not sure how I’m gonna make out with this career as a fiction writer.) The subjects I’d had polygraphed were a mixture of suspects, witnesses, complainants, and victims. I’d say that sixty percent of the subjects were truthful, thirty percent were lying, and ten percent were inconclusive but leaning toward truthful.

It makes sense, when you think about it, that the majority are truthful because they know it will work to their advantage. I can’t think of the number of times I’ve had subjects refuse to take the test, giving excuses everywhere from “Those things are rigged to frame me” to “I heard you get testicle cancer from it”. Then, of course, there’s, “My lawyer told me not to” to which I responded, “You don’t even have a lawyer.”

Before giving you some tips on how to fool a polygraph when you’re dead-ass lying, let’s look at what the thing is and how it works.

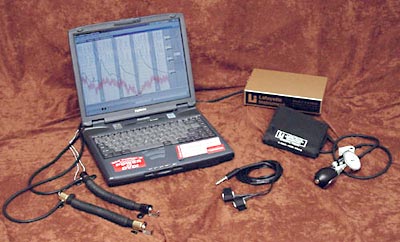

The word “polygraph” comes from the Greek word “fecalpolugraphos” which means “to sniff-out bullshit”. (Go ahead—call me a liar). Polygraphs have been around since the 1920s and have evolved from clunky paper-reel machines with ink-pen devices to modern laptops with automated scoring systems. Clinically, the process is known as psychophysiological detection of deception.

The instruments are a computerized combination of medical devices that monitor a subject’s physiological responses to a set of questions designed to put the subject under the stress; the stress associated with deception. The involuntary bodily functions include heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, galvanic skin conduction, and perspiration.

Polygraphic theory dictates that a subject will show a stress spike in some, or all, of these functions when asked a question and forced to knowingly lie. In a criminal investigation, the examination questions are formed between the polygraphist and the subject during an extensive pre-test interview.

There are four categories of questions—all must be answered “Yes” or “No”. Three categories are control questions and one is issue questions.

Category One is where the subject conclusively knows they’re truthful:

Q — Is your name Garry Rodgers? “Yes”

Q — Are you a retired police officer? “Yes”

Q — Do you write books? “Yes”

Category Two is asking the subject ambiguous questions:

Q — Is there life after death? “Yes”

Q — Did the chicken come before the egg? “No”

Q — Are you still beating your wife? “No”

Category Three has the subject intentionally lie:

Q — Were you kidnapped by aliens? “Yes”

Q — Did you ever ride a camel? “No”

Q — Were you knighted by the Queen? “Yes”

Category Four deals with the issues:

Q — Did you murder Jimmy Hoffa? “No”

Q — Do you know who murdered Jimmy Hoffa? “No”

Q — Do you know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa’s remains? “No”

Only “Yes” or “No” answers are acceptable during a polygraph examination because the issue has to be clear in the subject’s mind. Black and White. All clarification is worked-out in the pre-test interview. The subject is never surprised by the question, but the question order is completely unknown. This creates an atmosphere of anxiety as the subject waits to hear the questions that really matter.

The biggest concern that I’ve heard from people who are asked to submit to a polygraph is “What happens if I’m nervous?”

This is expected. Anyone, police officers included, would experience anxiety when being examined. Part of a polygraphist’s skill is to build a rapport with the subject and put them at relative ease before the questioning starts. One of the reasons in building this rapport is to get the subject to volunteer information that the investigation hasn’t uncovered. I’ve seen subjects give critical facts because the right questions weren’t asked during the investigation, and I’ve seen subjects fall apart and confess before being strapped into the chair.

This is expected. Anyone, police officers included, would experience anxiety when being examined. Part of a polygraphist’s skill is to build a rapport with the subject and put them at relative ease before the questioning starts. One of the reasons in building this rapport is to get the subject to volunteer information that the investigation hasn’t uncovered. I’ve seen subjects give critical facts because the right questions weren’t asked during the investigation, and I’ve seen subjects fall apart and confess before being strapped into the chair.

The key to successful polygraph examinations is the the examiner’s skill. The polygraph is just a tool—an extension of the examiner’s mind and voice.

So—given there’s proven science and skill behind polygraphs—how can you fool one?

Like I said, given a professional examiner, a competent subject, and a clear issue, polygraph results are remarkably accurate. There are always exceptions, and here’s some tips on how to pass the graph when you’re truly a liar.

1. Prepare well in advance.

2. Research and understand the process so you won’t feel oppressed. The examiner will take every advantage of your ignorance.

3. Know the issue(s) and know what the examiner is looking for.

4. Talk to someone who has experienced a test.

5. Approach the test as an extreme job interview. Dress for the job. Arrive on time. Sober. Rested. Do not reschedule. Make a good first impression.

6. Know that you’re going to be video and audio recorded.

7. Understand the test starts right when you arrive and ends when you leave. It’s not just the time you’re hooked to the instrument.

8. Be on guard. There will be trick questions in the pre-test interview. It’s part of the process.

9. Listen carefully to what the examiner says and respond accordingly. Do not try and monopolize the conversation. The examiner is not your friend, despite how nice she comes across in the pre-test. Her job is to get to the truth. Remember—you’re dealing with a highly trained professional who intimately knows psychology and human behavior. If her exam shows you’re deceitful, she’ll go for your jugular in the post-test.

10. Recognize the relevant and irrelevant control questions. Focus on what’s relevant and do not offer more information than what’s pertinent to the issue.

11. Play dumb. Don’t try to impress the examiner that you’ve studied up. You’ll only look stupid.

12. Breathe normally. Shortness of breath naturally triggers the other body functions to accelerate and it will increase nervousness.

13. Take lots of time to answer.

14. Think of something mentally stressful when answering a control question—like the time when you were a kid and your dog was hit by the train. That will raise the ‘normal’ graph peaks.

15. Think of something calming when answering issue questions—like getting a new puppy. That will flatten stress peaks.

16. Keep your eyes open during the questions. The examiner will ask you to close them because this significantly alters your sensory awareness and puts you at a disadvantage. This is very important.

17. Bite your tongue during every question except the truthful control ones. This levels the playing field.

So, who’s got away when facing a lie detector?

I call her The Mother From Hell. I investigated a bizarre case of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy—a rare form of child abuse where a parent causes harm to their child to bring attention to themselves. This woman repeatedly complained that her infant daughter was choking, then was caught by hospital staff with her hands around the little girl’s neck. She denied it. We polygraphed her. She blew the needles off the instrument and confessed. But, The Mother From Hell got off in court because they found her confession inadmissible due to it being “elicited under oppression” from the polygraph examination and subsequent interrogation. It was a total horseshit ruling.

Gary Ridgway, The Green River Serial Killer from Seattle, strangled over fifty women in the 1980’s. He was on police radar early in the serial killing investigation, ‘passed’ a polygraph, and got warehoused as a suspect. He went on to kill many more before being caught on DNA.

So, can you fool the polygraph?

Maybe, but I doubt it.

The best advice I can give is, if you tell lies, don’t take a lie detector.

———

Over to you, Kill Zoners. Has anyone out there taken a polygraph examination? Would you take one? And has anyone ever used a polygraph examination scene in their books?

———

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating unexpected and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry passes himself off as a crime writer and enthusiastic indie publisher. Possibly a podcaster, too. 😉

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating unexpected and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry passes himself off as a crime writer and enthusiastic indie publisher. Possibly a podcaster, too. 😉

One of Garry Rodgers’s writing projects is a series based on true crime cases he was involved in. Investigating them, that is. Not committing the crimes. Garry lives on Vancouver Island at Canada’s west coast where he hosts a popular blog that you simply must follow at Dyingwords.net. You can also connect with him via Twitter @GarryRodgers1.

Good morning, Garry. Great post here.

To answer your questions..no, no, and no.

You close with excellent advice. There’s no upside to undergoing that procedure.

Thanks, Oh Early Riser! If I was innocent… maybe. If I was guilty… I wouldn’t go within a mile of that contraption. Notice the “trap” in “contraption”.

In 1985, I took and passed a lie detector test.

I had applied for a part-time undercover job looking for employee theft at a supermarket and had my choice of either taking a lie detector test or undergoing a lengthy background check.

The questioning was different from what you describe, maybe because I was not being questioned as a criminal suspect, or because the procedure and technology are more sophisticated now.

The examiner was also the hiring person. He worked for an agency, not the supermarket. He did start out with the type of easy questions you describe, like confirming my name and date of birth. Then he began asking questions that required an answer other than yes or no.

For example, he asked me to solve a series of arithmetic problems I had to compute in my head. These started out simple, the addition or subtraction of two or three numbers. Then the problems turned into multi-step procedures, add two numbers, multiply by another, subtract, divide, and I faltered. Later, he told me the advanced arithmetic questions were supposed to confuse the interviewee so the examiner could establish a baseline graph measure for responses given under stress.

During the lie detector test, the examiner asked me to state a total dollar amount for anything I had stolen from a previous job. I said $2 (I had taken a notebook). I figured this admission might cost me the job. But later, the examiner told me another person who applied for the job admitted during the lie detector test that he had stolen a car the weekend before. He also told me it was possible to beat a lie detector test if you were convinced your lies were the truth.

I worked at the supermarket for about a month and never discovered any employee theft. Probably because during my first shift, I got made by a nineteen-year-old boy working with me in the bakery section. I was wearing a blazer and skirt because I had come from my day job. He asked me if I was a store detective because I wore “a suit.” I was able to answer no, truthfully, because I was not a store detective; they look for customer theft.

Taking the test was kind of fun, but I would not take one if I were a criminal suspect, especially if I were guilty.

Interesting comment, TL. I have never heard of a polygraph questioning series go other than “yes” and “no”. Often, the examinee tries to qualify their answer with a “yes, but…” or a “no, butt…” and the examiner has to cut that off. I’ve been asked (many times) if a psychopath can beat a polygraph and I think they can. The whole procedure depends on stress responses to knowingly be deceitful so if lying doesn’t bother the suspect then they probably won’t react in a way that indicates a lie.

Garry, I was going to ask about someone who simply doesn’t care one way or the other. A completely conscienceless person. But I suppose that would be a psychopath, wouldn’t it?

Hi RLMC! As the polygraph procedure is completely dependent on the subject’s state of mind – a subjective examination of their mindset – then it’s mind over matter. If the subject doesn’t mind about the subject matter then it doesn’t matter to them about lying and they’ll probably come across as appearing truthful. Wait – does this even make sense???

Haha. Oh what tangled webs….

Phineas Gage had no conscience. But he’d had a 1″ diameter rod blown through his frontal cortex by a gunpowder explosion. Bipolar people in their manic phase have little or no conscience.

Interesting information, Garry. Great post.

I’ve never taken a polygraph examination. I don’t plan to take one. I like the idea of using one in a book, especially with a guilty character passing the test.

And I will remember your “Garry’s Tips on Passing a Polygraph Test” after my next bank heist. (This comment was posted by an imposter.)

Have a truthful day!

Bank heists are getting harder and harder to do every day, Steve (if that is your real name). Damn modern technology like facial recognition.

As a volunteer for the Civilian Police Academy in Orlando, I had to take a polygraph test. I told the examiner I was a writer and he let me see the squiggly results on the screen after the test, which was a voice stress analysis.

On one of the ambiguous questions, even though I was being truthful, it registered enough so he asked me several times. On another one, where it was ambiguous enough so I thought my “no” could possibly be a “yes”, no reaction at all.

It was fascinating to me, how even running through things 3 times, knowing the questions, the machine picked up the deliberate lies I was told to say for things like “Is the wall blue” when it was yellow, etc.

But the most memorable part for me was when we were going over the questions of the form we had to fill out. One said, “Have you ever done anything that if you did it today, would be a felony.” I’d answered no. Then the examiner said, “Based on your age, are you saying you never tried pot?”

Busted. But I’d honestly never thought of it as a felony, and it never came to mind when I was filling out the form. (This was about 15-20 years ago.)

Smoking pot was a felony, Terry. Up here is a mandatory requirement. Interesting you bring up voice stress analysis. There’s another procedure separate from polygraph examinations that deals only with voice stress and not monitoring the other involuntary responses. I’ve never seen one in operation, but I hear that a number of agencies use them in job interviews. For the criminal cases, I think the standard polygraph is almost universal.

What can I say? It was the 60s. 🙂

Re: the voice stress analysis – I think we went through the same procedure people applying for jobs went through, not the bad guys.

And that’s the way to fool the polygraph. Good stuff, Jim. 🙂

Fascinating, Garry! Thanks!

“The key to successful polygraph examinations is the the examiner’s skill. The polygraph is just a tool—an extension of the examiner’s mind and voice.”

Would you do a post sometime on how examiners are trained?

And thank you, Debbie. 🙂 Now that’s a good topic. I might just do that. My polygraph experience is with the RCMP – the Canadian version of the FBI. The RCMP operates the Canadian Police College in Ottawa and has one of the best polygraph schools anywhere. Polygraphist from around the world train there including some of the FBI examiners. The course is four months long followed by a two-year field understudy term before they’re turned loose on the public.

I was on the list to become a polygraphist, but I took early retirement from the force (20 years instead of the full-term 35) in order to stay on Vancouver Island and take up body snatching as a coroner.

I passed two a long time ago. The “examiner” was a crook. He added a question, “Do you think lie detectors can be fooled.” The needles jumped off the scale when I told him they could. Informed him of the lawsuit waiting for him if he tried to use the results. What a surprise. His report came back as ‘inconclusive’.

I always have questioned the wisdom of paying $300 for a “test” to recover a stolen $50. My co-worker freaked out totally and confessed to stealing before the exam ever started. That was what they really wanted.

There is no place for behavior like that in modern police polygraph examinations. To throw in a trick question without previewing it should cost a polygraphist their job. The program depends on a reputation of integrity. If the polygraphist can’t abide by the truth then it’s a sad, sad situation. Thanks for sharing your story, Alan.

It was a private company. The laws have changed since then. With any luck he is long gone.

Thanks Garry. You triggered a few scenes for my WIP. I think a lot of writers could pass one—we get into the heads of our characters so why not create a character who believes the lie? Just a thought.

And a very good thought to chew on, Patricia. 🙂

Another excellent post, Garry. Thanks!

I’ve never taken a polygraph.

And thank you, Elaine. I appreciate hearing this. I wouldn’t recommend getting into a situation where you were faced with the option.

Another fascinating post, Garry. I couldn’t lie my way out of a paper bag, so I’ll skip the polygraphs. I do enjoy writing, though, so here’s my answer:

I’ve never had a polygraph.

I never plan to take one.

I’d only make the tester laugh

To see I couldn’t fake one.

Have a great day. (Honestly!)

You made me chuckle, Kay. You’re a poet and I didn’t know it. Honestly, I have a great day every day. Life gets better as I get older. Enjoy your day!

When I get arrested can you be my one call?

Anything for a fellow Canadian, Ben. Thankfully, it’s rare to find a Canadian committing a crime. (Yeah. Right.)

Great info, Garry! I hope I never have to use it except in fiction.

When I worked as a dispatcher for our local sheriff’s department back in the ’80s, I did have to get the strap. I wouldn’t want to repeat the event.

I sailed through it, though. It didn’t even occur to me to try to lie.

Happy Thursday all . . .

“The strap.” I haven’t heard that term, Deb. And Happy Pre-Friday to you!

Those Americans! 🙂

Great post, Garry. Lots of great info here. My own experience with minor league criminals (substance abusers, juvenile miscreants, petty thieves etc) during my career in Library Land was that those individuals were very confident, unflinching liars, even when caught red-handed. It obviously went with the territory. Your post shows how the “truth verifier” would break through that confidence. Fascinating stuff.

If I every need to write a scene featuring one, this post will be a very helpful primer. As always, thanks!

It’s amazing how polished some liars are, Dale, even in a place of honor like a library. I spent a lot of time writing in our nearby university library. That was until Covid kicked me out. Libraries are great spots to people watch and listen, although people aren’t supposed to talk in a library. I’d be a liar, however, if I said I never broke that rule.

“Turns out I’m a terrible liar—not sure how I’m gonna make out with this career as a fiction writer.”

Still chuckling over that line. And thanks for another useful and entertaining column.

Glad to hear, Mike. So far, so good.

Dr. Todd Grande has a PhD in Counselor Education & Supervision. Here are his thoughts on lie detector tests:

https://youtu.be/I-q5vdQSbG8

Dr. Grande’s videos are pretty interesting. Most of them are true crime oriented, if you like to wallow in tales of people who are barmy in the crumpet behaving rudely.

I skipped through this video but am short on time right now. I’m going to watch it thoroughly a little later. Thanks for sharing, JGA.

I was scared to Google that phrase.

…barmy in the crumpet behaving rudely…

That’s a laugh-out-loud description if there ever was one! 🙂

I’m a Nigerian and I wasn’t sure if the Nigerian Police Force (NPF) are ever trained to use the polygraph machine or if they do use it, so I searched Google. All I found was a 2018 headline where candidates in a recruitment exercise into the force were required to ‘undergo compulsory polygraph tests to ensure they are not of questionable character.’

The idea of polygraph examination isn’t popular in this part of the world. But I’m certain this post will be helpful for me in a future WIP, so I’ll save it.

Thank you Mr Rodgers. By the way, it’s evening here.

Nice to hear from you, Stephen. It’s 9:35 in the morning here on Canada’s west coast, and it’s somewhat warm and rainy as it is at this time of the year. I understand that polygraph exams are very routine in the police hiring process today. I joined our force in 1978. Back then, polygraphs were widely used in criminal investigations but not in recruitment. I wish they had, because it might have vetted some of the undesirables who wormed their way through to getting a badge and a gun with no sensible ability to use them. Enjoy the rest of your Nigerian evening!

As far as I know, lie detectors are still not admissible in courts, right? So, I gather their main purpose is as an investigative tool?

And nope, never had one done. Don’t intend to. 🙂

That’s right, Kristy. I don’t know of any jurisdictions where polygraph “evidence” is admissible in any procedure, criminal or civil. Nor does the entire polygraph community want the examination results in court. The reason is not the reliability issue. It’s the resistance that subjects would have if they thought it would be incriminating – truthful or deceitful. Polygraphs are an investigative tool only, and the real value lies in the skill of the examiner to elicit truthful information.

I’ve read that a polygraph is admissible in court in some domestic cases in New Mexico.

Good stuff, Garry. I learned long ago that I can’t lie with a straight face. Personally, I think pathological liars have a much bigger problem at their core, like psychopathy or narcissism. I vaguely remember writing a scene with someone strapped to the polygraph, but it might be in one of my trunked novels (the mind’s always the first to go ?).

If I don’t talk to you before then, have an amazing weekend, my friend.

I recently dealt with a man who was the truest pathological liar and narcissist I’ve ever met. I was trying to help with his daughter’s unsolved murder (you might know of the case). The man turned out to be so bizarre that I refused to have anything further to do with him or the case. I even deactivated my very detailed post on the story. The guy was downright cold and nasty – he ticked off all the psychopathy boxes.

And you, too, BFF, have a nice November weekend. Hey! Thanksgiving’s coming up in New England soon. Is there going to be one less bird in the flock that frequents the Coletta yard? Turkey, I mean. Not crow. No one eats crow – that’s just a figure of speech.

After feeding all the turkeys in my yard, we may go with ham this year. 😉

Hi Garry, good, informative and entertaining post…as always. Think the story, and movie, about one of the inventors of the polygraph is very interesting. Have you seen it? Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, a 2017 film about American psychologist William Moulton Marston, who created the fictional character Wonder Woman. Worth a gander. Also, did you ever come across stories about Cleve Backster hooking up a polygraph machine to plants? Fascinating stuff. All the best.

Thanks, Bill. Appreciate hearing this. Nope, you’ve got me on both the film and the plants. Heading over to the Google right now.

Aldrich Ames beat the box multiple times. He was probably trained by his Russ handlers to beat the box so I conclude from that beating the polygraph is a skill that can be taught-all of which calls into question its reliability except with the most susceptible/gullible persons who may also be egotists who think they’re smarter than everyone else.

As you say the exam is only as good as the examiner. To the average defendant these motives and the qualifications of the examiner are opaque.

The combination of the appearance of scientific certainty and police deception/pressure to solve a case in the interview room is a recipe for extorting dubious confessions from gullible people.

Barry Scheck of the Innocence Project has much to say about the subject.

When I was practicing law I would never let any of my clients take a polygraph exam under any circumstances for any reason.

It’s a sucker’s game, like those tough man contests they have around here every now and again. Local yokels climb up in the ring with journeyman boxers and get their butts whipped.

Just my opinion. Your mileage may vary.

Fascinating account, and now I have to work the information into a story! I think that putting the polygraph into the hands of the villains rather than the police would up the stakes nicely and remove declining the interview as an option.