Reader Friday: Dinner With an Author

Image by Pavel Charny from Pixabay

You and your author of choice (see last week’s post) are enjoying your meal.

You can ask two questions. What would they be?

Reader Friday: Dinner With an Author

Image by Pavel Charny from Pixabay

You and your author of choice (see last week’s post) are enjoying your meal.

You can ask two questions. What would they be?

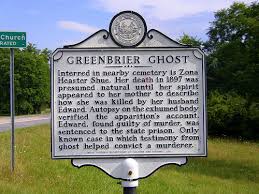

In July of 1897, Edward Stribbling (Trout) Shue was convicted of first-degree murder for strangling his wife and breaking her neck. Trout Shue’s trial, held in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, rested entirely upon circumstantial evidence that strangely proved Shue’s guilt—beyond a reasonable doubt—to jurors who were presented evidence from beyond the grave.

The “facts” included postmortem statements from Shue’s wife, Zona Heaster Shue, who was said to appear before her mother four weeks after death and reportedly told what truly occurred in her murder. It was the first—and only—time testimony from a ghost was admitted as evidence in a United States Superior Court trial, and it helped secure a conviction.

At 10:00 a.m. on January 23, 1897, twenty-three-year-old Zona Shue’s body was found by an errand boy. She was lying on the floor in their house, face down at the foot of the stairs, stretched with one arm tucked underneath her chest and the other extended. Her head was cocked to one side.

Trout Shue arrived home before the coroner, Dr. George Knapp, attended. Shue had already moved his wife’s body to their bed where he’d dressed her in a high-necked gown. As Dr. Knapp began examining Zona, Trout Shue exhibited overpowering emotions and cradled Zona’s head and her shoulders, sobbing and weeping. Dr. Knapp stopped his exam out of respect for the grieving spouse and signed-off the death to “everlasting faint”.

A traditional wake was held before Zona’s next-day burial and attendants noticed peculiar behavior from Trout Shue. When the casket was opened for viewing, he immediately placed a scarf over Zona’s neck as well as propping her head with a pillow and blanket. Shue then put on another spectacular show of grief and made it impossible for mourners to get a close look at her face.

A traditional wake was held before Zona’s next-day burial and attendants noticed peculiar behavior from Trout Shue. When the casket was opened for viewing, he immediately placed a scarf over Zona’s neck as well as propping her head with a pillow and blanket. Shue then put on another spectacular show of grief and made it impossible for mourners to get a close look at her face.

Zona Shue was buried in the Soule Chapel Methodist Cemetery in Greenbrier County. Initially, everyone who knew the Shues accepted Zona’s death as not suspicious—except for her mother, Mary Jane Heaster.

Mrs. Heaster disliked Trout Shue from the moment they met, and she suspected foul play was at hand. “The work of the devil!” Heaster exclaimed. She prayed every night, for four weeks on end, that the Lord would reveal the truth.

Then, in the darkness of night, when Mary Jane Heaster was wide awake, Zona’s spirit allegedly appeared.

It was not in a dream, Heaster reported. It was in person. First the apparition manifested as light, then transformed to a human figure which brought a chill upon the room. For four consecutive nights, Heaster claimed her daughter’s ghost came to the foot of her bed and reported facts of the crime that extinguished her life.

It was not in a dream, Heaster reported. It was in person. First the apparition manifested as light, then transformed to a human figure which brought a chill upon the room. For four consecutive nights, Heaster claimed her daughter’s ghost came to the foot of her bed and reported facts of the crime that extinguished her life.

Zona’s ghost was said to reveal a history of physical abuse from her husband. Her death resulted in a violent fight over a meal the night before she was found. Trout Shue was said to have strangled Zona, crushing her windpipe and snapping her neck “at the first joint”. To prove dislocation, Zona’s figure turned its head one hundred and eighty degrees to the rear.

Mary Jane Heaster steadfastly maintained her daughter’s ghost was real and Zona’s reports of the cause of her death were accurate. Heaster was so compelling in her paranormal description that she convinced local prosecutor, John Preston, to re-open the case.

Preston’s investigation found Trout Shue had a history of violence. In another State, he’d served prison time for assaults and thefts. He’d been married twice before—one other wife dying under mysterious circumstances. By now the Greenbrier community was reporting more peculiar behavior from Shue. He’d been making comments to the effect that “no one would ever prove I killed Zona”.

Combined with Coroner Knapp’s admission that he failed to conduct a thorough exam, Preston established sufficient grounds to exhume Zona’s body and conduct a proper postmortem examination.

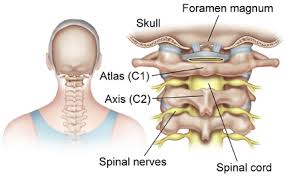

Zona was autopsied by three medical doctors on February 22, 1897 with the official cause of death being anoxia from manual strangulation compounded by a broken neck. Bruising consistent with fingermarks was noted on Zona’s neck, her esophagus was contused, and her first and second cervical vertebrae were fractured. Anatomically, they’re known as the C1 Atlas and the C2 Axis which combine to make the first joint at the base of the skull.

Zona was autopsied by three medical doctors on February 22, 1897 with the official cause of death being anoxia from manual strangulation compounded by a broken neck. Bruising consistent with fingermarks was noted on Zona’s neck, her esophagus was contused, and her first and second cervical vertebrae were fractured. Anatomically, they’re known as the C1 Atlas and the C2 Axis which combine to make the first joint at the base of the skull.

An inquest was held, and Trout Shue was summoned to testify. Although he denied being present at the time of Zona’s death and bearing culpability, he was unable to establish an alibi and was considered an unreliable, self-serving witness. It was ruled a homicide and Trout Shue was charged with her murder.

Trout Shue’s first-degree murder trial began in Greenbrier Circuit Court on June 22, 1897. A panel of twelve jurors was convened who heard evidence from a number of witnesses, including Shue himself.

John Preston was reluctant to subpoena Mary Jane Heaster as a witness, fearing her ghost story would damage credibility. However, Shue’s defense lawyer opened that can of worms and called Zona’s mother to the stand. Evidently, it backfired.

This verbatim excerpt is from the transcript of Mary Jane Heaster’s testimony. It’s still on record in the West Virginia State Archives:

Defense Counsel Question — I have heard that you had some dream or vision which led to this post mortem examination?

Witness Heaster Answer — It was no dream – she came back and told me that he was mad that she didn’t have no meat cooked for supper. But she said she had plenty, and said that she had butter and apple-butter, apples and named over two or three kinds of jellies, pears and cherries and raspberry jelly, and she says I had plenty; and she says don’t you think that he was mad and just took down all my nice things and packed them away and just ruined them. And she told me where I could look down back of Aunt Martha Jones’, in the meadow, in a rocky place; that I could look in a cellar behind some loose plank and see. It was a square log house, and it was hewed up to the square, and she said for me to look right at the right-hand side of the door as you go in and at the right-hand corner as you go in. Well, I saw the place just exactly as she told me, and I saw blood right there where she told me; and she told me something about that meat every night she came, just as she did the first night. She cames [sic] four times, and four nights; but the second night she told me that her neck was squeezed off at the first joint and it was just as she told me.

Q — Now, Mrs. Heaster, this sad affair was very particularly impressed upon your mind, and there was not a moment during your waking hours that you did not dwell upon it?

A — No, sir; and there is not yet, either.

Q — And was this not a dream founded upon your distressed condition of mind?

A — No, sir. It was no dream, for I was as wide awake as I ever was.

Q — Then if not a dream or dreams, what do you call it?

A — I prayed to the Lord that she might come back and tell me what had happened; and I prayed that she might come herself and tell on him.

Q — Do you think that you actually saw her in flesh and blood?

A — Yes, sir, I do. I told them the very dress that she was killed in, and when she went to leave me she turned her head completely around and looked at me like she wanted me to know all about it. And the very next time she came back to me she told me all about it. The first time she came, she seemed that she did not want to tell me as much about it as she did afterwards. The last night she was there she told me that she did everything she could do, and I am satisfied that she did do all that, too.

Q — Now, Mrs. Heaster, don’t you know that these visions, as you term them or describe them, were nothing more or less than four dreams founded upon your distress?

A — No, I don’t know it. The Lord sent her to me to tell it. I was the only friend that she knew she could tell and put any confidence it; I was the nearest one to her. He gave me a ring that he pretended she wanted me to have; but I don’t know what dead woman he might have taken it off of. I wanted her own ring and he would not let me have it.

Q — Mrs. Heaster, are you positively sure that these are not four dreams?

A — Yes, sir. It was not a dream. I don’t dream when I am wide awake, to be sure; and I know I saw her right there with me.

Q — Are you not considerably superstitious?

A — No, sir, I’m not. I was never that way before, and am not now.

Q — Do you believe the scriptures?

A — Yes, sir. I have no reason not to believe it.

Q — And do you believe the scriptures contain the words of God and his Son?

A — Yes, sir, I do. Don’t you believe it?

Q — Now, I would like if I could, to get you to say that these were four dreams and not four visions or appearances of your daughter in flesh and blood?

A — I am not going to say that; for I am not going to lie.

Q — Then you insist that she actually appeared in flesh and blood to you upon four different occasions?

A — Yes, sir.

Q — Did she not have any other conversation with you other than upon the matter of her death?

A — Yes, sir, some other little things. Some things I have forgotten – just a few words. I just wanted the particulars about her death, and I got them.

Q — When she came did you touch her?

A — Yes, sir. I got up on my elbows and reached out a little further, as I wanted to see if people came in their coffins, and I sat up and leaned on my elbow and there was light in the house. It was not a lamp light. I wanted to see if there was a coffin, but there was not. She was just like she was when she left this world. It was just after I went to bed, and I wanted her to come and talk to me, and she did. This was before the inquest and I told my neighbors. They said she was exactly as I told them she was.

Now, whether jury members accepted Mary Jane Heaster’s ghost story as being credible, or if it made any difference to their interpretation of the facts, will never be known. And it’s on record the trial judge cautioned jurors about the reliability of circumstantial evidence:

“There was no living witness to the crime charged against Defendant Shue and the State rests its case for conviction wholly upon circumstances connecting the accused with the murder charged. So the connection of the accused with the crime depends entirely upon the strength of the circumstantial evidence introduced by the State. There is no middle ground for you, the jury, to take. The verdict inevitably and logically must be for murder in the first degree or for an acquittal.”

The jury was out for an hour and ten minutes before returning to find Trout Shue guilty of murdering his wife, Zona, in the first degree. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and died of an epidemic disease three years later.

The jury was out for an hour and ten minutes before returning to find Trout Shue guilty of murdering his wife, Zona, in the first degree. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and died of an epidemic disease three years later.

I’d love to travel back in time and be a fly on the wall during that deliberation. What they discussed in that sequestered room has long gone to the grave, but I find Mary Jane Heaster’s testimony about Zona’s fractured vertebrae to be downright spooky.

———

What about you Kill Zoners? From reading Mrs. Heaster’s evidence, do you find her credible? And, by all means, please share with us your true ghost stories!

———

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating sudden and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry’s come back from the forensic dead and has reincarnated himself as a crime writer.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating sudden and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry’s come back from the forensic dead and has reincarnated himself as a crime writer.

Vancouver Island on Canada’s west coast is the haunting grounds for Garry Rodgers. In spirit, he maintains a popular blog at DyingWords.net and he occasionally floats in and out on Twitter — @GarryRodgers1. You can find Garry’s flesh-and-blood crime writing works on leading E-tailers —Amazon, Kobo, Apple, Nook, and Google.

Folks, I’m not going to try and bluff my way through this post. As I write this, I have what I believe is the flu. Remember the flu? That other respiratory malady that has been around for years? I did get tested for the new malady, and with negative results. So, as I enter my seventh day of fever, I find myself at a loss for writing advice that anyone could possibly find interesting.

Instead, as we here at The Killzone Blog wander up to our annual holiday hiatus, I’ll take this opportunity to express my gratitude to our subscribers and lurkers for all your support over these many years.

Next time we see each other, we’ll be in the embrace of a brand new year. I wish everyone health, prosperity and happiness.

You better make them care…It better be quirky or perverse or thoughtful enough so that you hit some chord in them. Otherwise, it doesn’t work. I mean we’ve all read pieces where we thought, “Oh, who gives a damn?” — Nora Ephron.

I feel like now people want more of a mirror. They want to see themselves in the book that they’re reading. — David Sedaris

By PJ Parrish

Well, it’s officially Christmas season. I know this because Ralphie is whining about getting a Red Ryder air rifle. Every time A Christmas Story comes on, I am reminded of my own childhood. But I’m also reminded how dependent writers are on our powers of observation and also our storehouses of life experience. And how we use that to connect with our readers.

This point is especially clear to me because I’ve been reading Nora Ephron’s Wallflower at the Orgy, her dispatches as a reporter about the cultural upheavals of the late ’60s. Here’s the opening:

Some years ago, the man I am married to told me he had always had a mad desire to go to an orgy. Why on earth, I asked. Why not, he said. Because, I replied, it would be just like the dances at the YMCA I went to in the seventh grade—only instead of people walking past me and rejecting me, they would be stepping over my naked body and rejecting me. The image made no impression at all on my husband. But it has stayed with me—albeit in another context. Because working as a journalist is exactly like being the wallflower at the orgy. I always seem to find myself at a perfectly wonderful event where everyone else is having a marvelous time, laughing merrily, eating, drinking, having sex in the back room, and I am standing on the side taking notes on it all.

Nora Ephron, director (Photo by Vera Anderson/WireImage)

Which pretty much summarized how I often felt during the ’60s and later when I worked as a reporter. But that’s the beauty of a great writer like Ephron, and why I am drawn to essayists. They see things more sharply than average folk. And they spin what they see into great stories that anyone can relate to. Which is pretty much what we novelists should be trying to do.

You have to connect. But easier said than done, as any writer knows. I remember reading a First Novel Edgar winner a couple years back. Man, the writing just sang! Gorgeous description, a lean neo-noir sensibility. But I always felt as if the writer was holding back emotionally. And this arms-length style eventually left me thinking, “who gives a damn?”

You have to connect. Some things to think about as you grapple with this.

Make your subject relatable in experience. Nora Ephron wrote a terrific essay called “A Few Words About Breasts.” It was about her agony, as a tomboy, waiting for her breasts to “develop.” When she begged her mother for a bra, her mom said “What for?” She recounts the horror of going alone to the department store and getting fitted for a size 28AA. When I read it, I was smiling, nodding and ultimately crying.

Many moons later, I happened upon her essay on aging gracefully called “On Maintenance.” Best line about how getting hair highlights changed her life: “…a little like that first brandy Alexander Lee Remick drank in Days of Wine and Roses.”

Use Your Experiences to Find Your Own Voice. Another of my favorite writers is also an essayist — David Sedaris. Why do his essays connect with readers? Because he writes with wit and humility of his own experiences. He is a storyteller you want to spend your hours with. His essay on learning French “Me Talk Pretty One Day” articulated all the terror I felt in my first French adult ed course: “Learning French is a lot like joining a gang in that it involves a long and intensive period of hazing.” I’m now taking online Babbel courses now and every time I am “buzzed” for incorrect pronunciation — I have a heavy Detroit/Michigan accent, so I will never say anything in French pretty — I think of Sedaris. He’s got some really good advice for writers. Click here. This one is among my favorites:

Sad stories, dashed dreams, and memorable mistakes are ammunition for writers. Any experience can be converted into a story, and rough experiences often make the best stories. As a writer, failure is soil for growing heartfelt stories. Vulnerability is a powerful draw. Write down your biggest failures, then review the list to see which ones can be marshaled into relatable stories for your readers.

And about that voice thing? Don’t sweat it too much. When you’re just starting out, you might not be able to articulate exactly what you are trying, in your heart and soul, to get across. So be content with trying to become the best damn storyteller you can. If you are successful at that, the voice thing will emerge by itself. As Neil Gaiman says:

After you’ve written 10,000 words, 30,000 words, 60,000 words, 150,000 words, a million words, you will have your voice, because your voice is the stuff you can’t help doing.”

Which leads me to my final essayist who influenced me as a writer. I first encountered Jean Shepherd’s writing in the ’70s when I was reading Car & Driver magazine. (don’t ask…my ex-husband, a race car nut from Indy was a subscriber.) I loved his columns. He went on to write for Playboy, New York Times and others. Time magazine once described him as a “comic anthropologist.” His talent was noticing and using the mundane details of daily life to tell his stories, filtering them through a sensibility that was, by turns, funny, absurd, sarcastic, and often sad. (For the record, Shepherd hated the word “nostalgia.” I found this out when I interviewed him for a profile in the Fort Lauderdale News.)

I loved his short story about the awful rites of prom-going, “Wanda Hickey’s Night of Golden Memories” because every detail is acute. And also because I was poor pitiful Wanda:

I began to notice Wanda’s orchid leering up at me from her shoulder. It was the most repulsive flower I had ever seen. At least 14 inches across, it looked like some kind of overgrown Venus’s flytrap waiting for the right moment to strike. Deep purple, with an obscene yellow tongue that stuck straight out of it, and greenish knobs on the end, it clashed almost audibly with her turquoise dress. It looked like it was breathing, and it clung to her shoulder as if with claws.

As I glided back and forth in my graceful box step, my left shoulder began to develop an itch that helped take my mind off of the insane itch in my right shoulder, which was beginning to feel like army of hungry soldier ants on the march. The contortions I made to relieve the agony were camouflaged nicely by a short sneezing fit brought on by the orchid, which was exhaling directly into my face. So was Wanda, with a heady essence of Smith Brothers cough drops and sauerkraut.

But Shepherd is best known for A Christmas Story. You’ve seen it. It runs on a loop during the holidays, the 1983 movie about Ralphie, his long-suffering chenille-robed mom and his old man who lusts after a lamp in the shape of a fish-netted gam. The movie is based on some chapters from Shepherd’s first book In God We Trust (All Others Pay Cash), which were based on Shepherd’s childhood in Hammond, Ind. Why is the movie evergreen? Here’s what Shepherd told an interviewer in 1971:

“You can tell a story about anything. But the only stories that have any fidelity, any feeling, are stories that either did happen to you or conceivably could have happened to you.”

In other words, to be a great storyteller, you have to connect. Merry Christmas, y’all.

Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

Misdirection is the intentional deflection of attention for the purpose of disguise, and it’s a vital literary device. To plant and disguise a clue so the reader doesn’t realize its importance takes time and finesse.

The most important thing to remember is to play fair. Clues must be in plain sight. We cannot reveal a clue that wasn’t visible earlier. That’s cheating.

A few years ago, I read a novel about [can’t name the profession without giving away the title]. The protagonist located the dead and solved every mystery with invisible clues. After I whipped my Kindle across the room, I took a deep breath and skimmed the story searching for the clues. Never found one. Not one! The author’s name now sits at the pinnacle of my Do Not Read list.

A key feature of good misdirection means you brought attention to the clue, and the reader still missed it.

A magician uses three types of misdirection:

Notice any similarities to writing?

Misdirection can be either external or internal. External would be when the author misdirects the reader. Internal is when a character misdirects another character.

Misdirection is different than misinformation. We should never outright lie to the reader. Rather, we let them lie to themselves by disguising the clue(s) as inconsequential.

How do we do that?

When you come to a part of the story where nothing major occurs, slip in a clue. Or include the detail/clue while fleshing out a character’s life.

Examples:

One character chats with another as they drive to a designated location. Is the locale a clue in and of itself?

What about the title of the book? The reader has seen the title numerous times, yet she never gave it much thought until the protagonist reveals its meaning to the plot.

Clandestine lovers meet in a hideaway. While there, one of the characters notices a symbol or sign. Later in the story, she finds another clue that relates to the sign or symbol. Only now, she has enough experience to interpret its true meaning.

A kidnapper chalks an X on a park bench to signal the drop-off spot. What if a stray dog approaches the kidnapper? If he reads the dog’s tag to find his human, the clue takes center stage, yet it’s disguised as inconsequential.

In all four examples the arrival of the clue seems insignificant at first. The reader will notice the clue because we’ve drawn attention to it, but we’ve framed it in a way that allows the character to dismiss it. Thus, the reader will, too.

False Trails

The character knows the clue is important when she finds it, but she misinterprets its meaning, leading her down a dead end.

What if we need to supply information on a certain topic, but we don’t want the reader to understand why yet? If we take the clue out of context and present it as something else—something innocuous or insignificant—we’ve misdirected the reader to reach the wrong conclusion.

An important factor of misdirection is that the disguise must make sense within the confines of the scene. It should also further the plot in some way.

“Misdirection can be used either strategically or tactically. Strategically to change the whole direction of a story, to send it off into a new and different world, and have the reader realize that it’s been headed that way all along. Tactically to conceal, obscure, obfuscate, and camouflage one important fact, to save it for later revelation.”

— The Writer magazine

Character Misdirection

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite.

Character misdirection is when the protagonist (and reader) believes a secondary character fulfills one role when, in fact, he fulfills the opposite.

Two types of character misdirection.

These two characters are not what they seem on the surface. They provide opportunities for dichotomy, juxtaposition, insights into the protagonist, theme, plot, and plot twists. They’re useful characters and so much fun to write.

A false ally is a character who acts like they’re on the protagonist’s side when they really have ulterior motives. The protagonist trusts the false ally. The reader will, too. Until the moment when the character unmasks, revealing their false façade and true intention.

A false enemy is a character the protagonist does not trust. Past experiences with this character warn the protagonist to be wary. But this time, the false enemy wants to help the protagonist.

When Hannibal Lecter tries to help Clarice, she’s leery about trusting a serial killing cannibal. The reader is too.

What type of character is Hannibal Lecter, a false ally or false enemy?

An argument could be made for both. On one hand, he acts like a false enemy, but he does have his own agenda. Thomas Harris blurred the lines between the two. What emerged is a multifaceted character that we’ve analyzed for years.

When crafting a false ally or false enemy, it’s fine to fit the character into one of these roles. Or, like Harris, add shades of gray.

Mastering the art of misdirection is an important skill. It’s especially important for mysteries and thrillers. I hope this post churns up new ideas for you.

Do you have a false ally or false enemy in your WIP? What are some ways you’ve employed misdirection?

This is my final post of 2021. Wishing you all a joyous holiday season. See ya in the New Year!

Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime, Pretty Evil New England is on sale for $1.99. Limited time. On Wednesday, Dec. 15, the price returns to full retail: $13.99.

Female killers are often portrayed as caricatures: Black Widows, Angels of Death, or Femme Fatales. But the real stories of these women are much more complex. In Pretty Evil New England, true crime author Sue Coletta tells the story of these five women, from broken childhoods to first brushes with death, and she examines the overwhelming urges that propelled these women to take the lives of more than one-hundred innocent victims. If you enjoy narrative nonfiction/true crime, Pretty Evil New England is on sale for $1.99. Limited time. On Wednesday, Dec. 15, the price returns to full retail: $13.99.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

We’re writers. We know what that means. We’re always on the job. Our minds, often apart from our intentions, keep the story wheels churning.

Like when we go to comfort a loved one in a time of need. We take their hand and issue words of consolation, while our writer mind is thinking, This would make a great scene. I wonder how I can work it into a book?

Nothing to apologize for. It’s how we roll. We write even when we’re not at the keyboard. So why not be intentional about it? Here are some of the methods I use to incentivize the Boys in the Basement:

Mind Mapping

We all know about brainstorming. That’s where we let the mind run free, without judgment, generating as many ideas as possible. The best way to get good ideas is to get lots and lots of them and only later cast aside the least promising ones.

I have found that a great aid to brainstorming is the mind map. Mapping is a way to visually link the random thoughts you jot down into some level of coherence. (A good book on this process is Writing the Natural Way by Gabriele Lusser Rico.)

I use mind maps in two ways. First is to get ideas for flash fiction and short stories for my Patreon community. I often use a nifty set of cards called The Storymatic. Their ad line is “Six trillion stories in one little box. Which one will you tell?” It’s a set of 500 cards of two types. One type is a setting or situation, the other is a kind of character. I’ll draw one of each at random and put them together to see what comes up.

The other day I drew the cards “Survivor” and “Message in chalk on sidewalk.” I wrote those down on opposite sides of a page and circled them. Then I began the map. Here’s what it looked like (click to enlarge):

As I went along I kept coming back to the doodle of the chalk drawing. The Boys were trying to tell me something. I listened, and an idea for a short story popped up. As I pondered a little more I dropped the Survivor part altogether (you’re not wedded to anything when you mind map) and in a few minutes had the complete concept.

The other way I map is when I have a particular plot problem to work out. I’m finishing up a novelette in my Bill Armbrewster series about a Hollywood studio troubleshooter in the 1940s. As I closed in on the ending I realized there was a key element earlier in the story that needed clearing up. It involved the filching of a photo from a movie star’s dressing room (Bette Davis’s, to be exact.) So on paper I wrote “Who stole the pic?” and started mapping. In a few minutes I had my answer.

Sound and Music

I know some writers who want silence as they type. But for creativity there is research that suggests a little ambient noise helps. When I’m in my office I usually put on Coffitivity or New York street sound.

Often I’ll do my mind mapping while listening to music. If I’m thinking of suspense—which is most of the time—I’ll put on a playlist of suspense movie soundtracks (my favorite being the Hitchcock scores of Bernard Herrmann). I have other lists of soundtracks that stir up other emotions.

I don’t usually use music with lyrics for this, but I understand a certain Mr. King used to crank up the rock for his work. So I’ll make occasional use of the greatest rock era of all time—the 1970s (go ahead, try to prove me wrong).

Bedtime Prompt

Nice thing about the Boys is that they don’t take time off. So give them direction at night.

If you’re working on a novel, spend five concentrated minutes just before shut eye thinking about the plot, characters, or a scene.

Sometimes I’ll write a problem down on a pad on my bedside table. What is Romeo going to do about the bomb?

In the morning, as soon as possible, write down whatever is bubbling in your head, even if it doesn’t make sense at first. Somewhere in there is a message to you, though it may be in code!

Quiet Mind

I wonder if you’ve noticed a slight increase in stress levels these days.

Ahem.

We’ve all been there. We’ve all had days when we make the coffee nervous. As I pointed out in a previous post, all the mental effort that goes into navigating the mandate marshlands takes a toll on our creativity and writing energy.

Add to that the constant stream of vitriol spewing out of every communicative orifice in our civilized nation, and you’ve got a recipe for potential creative shutdown.

So what can you do? You can quiet your mind a couple of times a day. A popular practice for this is mindfulness.

Mindfulness isn’t some mystic practice that requires a robe and the lotus position. You won’t end up in a Tibetan monastery (unless you really want to). It’s just a way to practice calming down. In old movies the usual step was some guy saying, “I need a drink.” Many follow that path even now. Better is 10-15 minutes of mindfulness. Plus, instead of a hangover, you’ll get a burst of creativity afterward. Four ways I’ve done it:

Sitting: Sit in a comfortable spot, with your back straight (not leaning against the backrest). Feet flat on the floor, hands resting on your legs. Breathe easily in through your nose and out through your mouth. Listen to your breathing. Note the way your abdomen and chest move. Find an object in the room to concentrate on. Look at it, noting everything about it. Don’t analyze it, just look at it. It’ll be hard to do this at first. Your thoughts will easily distract you (“I have to remember to go to the store…Where did I leave my reading glasses?…Did The Rock really make another movie?”). When that happens, recognize you’ve had the thoughts and gently return to breathing and concentrating.

Walking: Don’t mistake this for taking a walk for exercise. Instead, you only need a small space outside. I walk around my pool. Do it slowly, nose-mouth breathing, noticing whatever is around you.

Driving: (Especially helpful in L.A. traffic.) Instead of grumbling about being late, breathe easy and focus on the taillights in front of you. Notice their design and texture. Make sure you’ve turned off talk radio and the news. Ignore bumper stickers.

Waiting in Line: Instead of grousing how long your line is—or how all the other lines seem to move faster—be grateful for the opportunity to have some quiet time. Don’t pick up a People magazine to see if Kim and Kanye are getting back together. Just breathe easily and note all the colors you see in the objects around you.

These are some of the ways I write when I’m not writing. What have you noticed about your own time away from the keyboard? When do ideas tend to pop up from the basement? Do you do anything to incentivize the Boys?

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops.” Stephen King.

I can’t agree more. I fear I’ll step on some toes here, because there are hundreds of authors who love adverbs and will argue ‘til the cows come home that they improve their writing. I can’t go there. Oh, I know they’re in my own novels and columns, they pop up without notice in the first drafts, but I do my best to weed them out and rewrite the sentences to make them better than the original.

A few years ago, I packed a couple of books in a carry-on, intending to spend the almost nine hour flight to Hawaii with my nose in a book. I’ve written novels and newspaper columns on planes, and have edited several manuscripts while hanging in the air over various parts of this great nation, but I prefer to read.

I’d purchased a much-touted post-apocalyptic novel from Amazon and had been looking forward to losing myself in the tale (I got hooked on those when I read Alas Babylon fifty years ago). The flight leveled off, I ordered a Bombay Sapphire and tonic, (they had my gin in stock, huzzah!) and settled back with The Novel That Shall Not Be Named (not the real title). The problem began in paragraph one and I knew the book was going to be a wall-banger when I read:

He headed for the baggage claim tiredly, hoping this would be the last time for a while.

Good lord. That sentence required two deep swallows of Bombay before I could continue, and I did, hoping the writing would get better.

Maybe that one slipped through the editing process.

Here we go again. Still on the first page, I read the word “battered” twice in two short, consecutive paragraphs and sighed.

Please get better.

In the next couple of paragraphs, our protagonist leaves the airport, lights a cigarette, and outside for his delayed ride. Unlike him, we didn’t have to wait long for more adverbs.

“Hey pal, can’t you read?” someone said sharply.

“Does your daddy know you’re out playing cop?” he said snidely.

Sigh.

There were two more books in my carry-on, because I never go anywhere without backup, but reading that book was like watching a train wreck. I couldn’t stop, and my fascination with bad writing and boring sentences kept me from throwing the hefty novel against the bulkhead.

There were other problems as well, though I won’t dwell on them other than to say the author fell back on using character’s name in conversation over and over in order to identify the speaker, something I discussed in my last post.

His protagonist and other characters also snapped, spat, snarled, growled, grunted, barked, remarked (unnecessary), shouted, screamed (he just loved for verbs to follow dialogue), but I couldn’t get past the adverbs scattered like rice at a wedding.

Unceremoniously, firmly, loudly, tiredly (again), actually, expertly, apologetically, evenly, and finally (four times), all in the first short chapter.

And it was the way he used them. For example, he insisted on using adverbs that were redundant to the verb they modified.

“Amy whispered quietly to her mother.”

Uh, whispering is already quiet, so we don’t need it. That’s like…

He screamed loudly. Or, Amy drove quickly to the store.” This adverb is modifying a weak verb, so maybe Amy can “jump in her car and race to the store.”

Then there’s the adverb “very,” which I propose is the gateway word leading to Hell Road. Some writers use it the same as so many people who insist that the whole world and everything in it is amazing.

Amy was very tired.

Nope. Amy was exhausted, wrung out, beat, worn out, bushed, dog-tired or even wiped out, but for cryin’ out loud, lift your vocabulary! Her dogs were barking, she was dead on her feet!!! Jeeze!

I believe Mr. King also said adverbs prefer the passive voice, and seem to have been created with the timid word in mind. He was dead-on with The Novel That Shall Not Be Named. I closed it at the beginning of the second chapter. With no suitable walls to throw it against, and fearing aggressive responses from the other passengers if I heaved it into the aisle, I stuck the offending work in the seat pocket in front of me.

It’s something I regret today, because I figure some unsuspecting soul picked it up and found themselves subjected to poor writing. I regret leaving it on that plane for another reason, because I often use it these days as a teaching tool (I found another copy in a bookstore, which means I bought the damned thing twice). The Novel That Shall Not Be Named is a good, bad example of how adverbs allow the writer to be lazy, instead of allowing the work to support itself with well-constructed, thoughtful sentences.

Let’s go back to the first example from The Novel That Shall Not Be Named. I’ll refresh your memory:

He headed for the baggage claim tiredly, hoping this would be the last time for a while.

How about:

Exhausted from the long flight from Dusseldorf, he joined the herd of passengers making their lemming-like way to the baggage claim, hoping he wouldn’t have to travel overseas again for a while.

Now, I know we can argue the point to excess, but to me, it reads better with some context and gives the sentence a little more gas. Here are a few more examples.

I had her wrist firmly in hand.

I squeezed her wrist.

She closed the door firmly.

She slammed the door.

The horse loped around the arena speedily.

Comfortable in the saddle, Matt loped around the arena.

He stuttered haltingly.

How about a simple, “He stuttered.”

Read your manuscript carefully.

Read your manuscript with a critical eye toward those annoying adverbs.

Again, they tend to prop up weak or listless sentences, and that’s when I can’t stand those little buggers. When you find them, re-write the sentence and it will almost always be better than the original.

This example from Daily Writing Tips is a perfect example of these useless weeds (King’s description).

“Adverbs, like adjectives, have gotten a bad rap for their cluttering qualities. They are ever so useful, and so applicable and adaptable that writers often employ them mindlessly and indiscriminately. But which of the three adverbs in the preceding phrase (not only mindlessly and indiscriminately but also often) must I mercilessly vaporize with the Delete key?”

How about “…writers employ them without conscious thought,” or maybe, “…writers employ them with unconsidered, gleeful abandon,” or “…writers should find a better way to construct their sentences.”

I don’t think budding authors even know they’re being lazy, or maybe they don’t recognize adverbs for what they are. After reading On Writing by Mr. King, I went back and combed through my first manuscript, excising as many adverbs as I could find, and the truth be told, my writing sparkled when I deleted most of them.

Just this past Sunday, a friend asked if he could pick my brain a little about becoming an author. I have an idea for a non-fiction book.”

“I’ve written a lot of how-to magazine articles, but fiction is completely different and that’s where I’m comfortable.” I suggested some conferences or writing classes he could take to get started, but he had other ideas.

“I just want to talk about language and style.” He glanced around, as if worried that someone was listening in.

I couldn’t resist having a little fun with him. “I can give you a quick lesson now.”

“Okay, shoot.”

“Write conversationally and avoid adverbs.”

Nodding, he wrote the sentence down on a scrap piece of paper.

It was just too easy, because he was concentrating on the subject at hand, much like writing the first draft of a manuscript, and those adverbs weren’t yet resonating. “Remember, no adverbs if you can help it. Seriously. That’s the best advice I can offer right now.”

“Absolutely. Thanks for your help.”

“You’re welcome.”

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops.” Stephen King.

I can’t agree more. I fear I’ll step on some toes here, because there are hundreds of authors who love adverbs and will argue ‘til the cows come home that they improve their writing. I can’t go there. Oh, I know they’re in my own novels and columns, they pop up without notice in the first drafts, but I do my best to weed them out and rewrite the sentences to make them better than the original.

A few years ago, I packed a couple of books in a carry-on, intending to spend the almost nine hour flight to Hawaii with my nose in a book. I’ve written novels and newspaper columns on planes, and have edited several manuscripts while hanging in the air over various parts of this great nation, but I prefer to read.

I’d purchased a much-touted post-apocalyptic novel from Amazon and had been looking forward to losing myself in the tale (I got hooked on those when I read Alas Babylon fifty years ago). The flight leveled off, I ordered a Bombay Sapphire and tonic, (they had my gin in stock, huzzah!) and settled back with The Novel That Shall Not Be Named (not the real title). The problem began in paragraph one and I knew the book was going to be a wall-banger when I read:

He headed for the baggage claim tiredly, hoping this would be the last time for a while.

Good lord. That sentence required two deep swallows of Bombay before I could continue, and I did, hoping the writing would get better.

Maybe that one slipped through the editing process.

Here we go again. Still on the first page, I read the word “battered” twice in two short, consecutive paragraphs and sighed.

Please get better.

In the next couple of paragraphs, our protagonist leaves the airport, lights a cigarette, and outside for his delayed ride. Unlike him, we didn’t have to wait long for more adverbs.

“Hey pal, can’t you read?” someone said sharply.

“Does your daddy know you’re out playing cop?” he said snidely.

Sigh.

There were two more books in my carry-on, because I never go anywhere without backup, but reading that book was like watching a train wreck. I couldn’t stop, and my fascination with bad writing and boring sentences kept me from throwing the hefty novel against the bulkhead.

There were other problems as well, though I won’t dwell on them other than to say the author fell back on using character’s name in conversation over and over in order to identify the speaker, something I discussed in my last post.

His protagonist and other characters also snapped, spat, snarled, growled, grunted, barked, remarked (unnecessary), shouted, screamed (he just loved for verbs to follow dialogue), but I couldn’t get past the adverbs scattered like rice at a wedding.

Unceremoniously, firmly, loudly, tiredly (again), actually, expertly, apologetically, evenly, and finally (four times), all in the first short chapter.

And it was the way he used them. For example, he insisted on using adverbs that were redundant to the verb they modified.

“Amy whispered quietly to her mother.”

Uh, whispering is already quiet, so we don’t need it. That’s like…

He screamed loudly. Or, Amy drove quickly to the store.” This adverb is modifying a weak verb, so maybe Amy can “jump in her car and race to the store.”

Then there’s the adverb “very,” which I propose is the gateway word leading to Hell Road. Some writers use it the same as so many people who insist that the whole world and everything in it is amazing.

Amy was very tired.

Nope. Amy was exhausted, wrung out, beat, worn out, bushed, dog-tired or even wiped out, but for cryin’ out loud, lift your vocabulary! Her dogs were barking, she was dead on her feet!!! Jeeze!

I believe Mr. King also said adverbs prefer the passive voice, and seem to have been created with the timid word in mind. He was dead-on with The Novel That Shall Not Be Named. I closed it at the beginning of the second chapter. With no suitable walls to throw it against, and fearing aggressive responses from the other passengers if I heaved it into the aisle, I stuck the offending work in the seat pocket in front of me.

It’s something I regret today, because I figure some unsuspecting soul picked it up and found themselves subjected to poor writing. I regret leaving it on that plane for another reason, because I often use it these days as a teaching tool (I found another copy in a bookstore, which means I bought the damned thing twice). The Novel That Shall Not Be Named is a good, bad example of how adverbs allow the writer to be lazy, instead of allowing the work to support itself with well-constructed, thoughtful sentences.

Let’s go back to the first example from The Novel That Shall Not Be Named. I’ll refresh your memory:

He headed for the baggage claim tiredly, hoping this would be the last time for a while.

How about:

Exhausted from the long flight from Dusseldorf, he joined the herd of passengers making their lemming-like way to the baggage claim, hoping he wouldn’t have to travel overseas again for a while.

Now, I know we can argue the point to excess, but to me, it reads better with some context and gives the sentence a little more gas. Here are a few more examples.

I had her wrist firmly in hand.

I squeezed her wrist.

She closed the door firmly.

She slammed the door.

The horse loped around the arena speedily.

Comfortable in the saddle, Matt loped around the arena.

He stuttered haltingly.

How about a simple, “He stuttered.”

Read your manuscript carefully.

Read your manuscript with a critical eye toward those annoying adverbs.

Again, they tend to prop up weak or listless sentences, and that’s when I can’t stand those little buggers. When you find them, re-write the sentence and it will almost always be better than the original.

This example from Daily Writing Tips is a perfect example of these useless weeds (King’s description).

“Adverbs, like adjectives, have gotten a bad rap for their cluttering qualities. They are ever so useful, and so applicable and adaptable that writers often employ them mindlessly and indiscriminately. But which of the three adverbs in the preceding phrase (not only mindlessly and indiscriminately but also often) must I mercilessly vaporize with the Delete key?”

How about “…writers employ them without conscious thought,” or maybe, “…writers employ them with unconsidered, gleeful abandon,” or “…writers should find a better way to construct their sentences.”

I don’t think budding authors even know they’re being lazy, or maybe they don’t recognize adverbs for what they are. After reading On Writing by Mr. King, I went back and combed through my first manuscript, excising as many adverbs as I could find, and the truth be told, my writing sparkled when I deleted most of them.

Just this past Sunday, a friend asked if he could pick my brain a little about becoming an author. I have an idea for a non-fiction book.”

“I’ve written a lot of how-to magazine articles, but fiction is completely different and that’s where I’m comfortable.” I suggested some conferences or writing classes he could take to get started, but he had other ideas.

“I just want to talk about language and style.” He glanced around, as if worried that someone was listening in.

I couldn’t resist having a little fun with him. “I can give you a quick lesson now.”

“Okay, shoot.”

“Write conversationally and avoid adverbs.”

Nodding, he wrote the sentence down on a scrap piece of paper.

It was just too easy, because he was concentrating on the subject at hand, much like writing the first draft of a manuscript, and those adverbs weren’t yet resonating. “Remember, no adverbs if you can help it. Seriously. That’s the best advice I can offer right now.”

“Absolutely. Thanks for your help.”

“You’re welcome.”

Reader Friday: Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner

You can have dinner with any currently living author. The rules: It’s at your house. You have to cook. No take-out, no delivery. You cannot ask the author about preferences. For the sake of this exercise, there are no food allergies, dietary restrictions.

You can have dinner with any currently living author. The rules: It’s at your house. You have to cook. No take-out, no delivery. You cannot ask the author about preferences. For the sake of this exercise, there are no food allergies, dietary restrictions.

Who’s coming to dinner?

What are you going to prepare?

Based on early comments, it looks like my one-on-one dinner with an author has been hijacked into dinner parties. You guys are going to have trouble with next week’s Reader Friday. 😉

By Elaine Viets

Did you ever say this? “I’m trying to write a short story, but I’m blocked. I’m getting nowhere.”

Did you ever say this? “I’m trying to write a short story, but I’m blocked. I’m getting nowhere.”

That happens to every writer. It certainly happens to me. Short stories are hard to write. In some ways, they may be harder to writer than novels. Here are a few tips for when you feel blocked working on your short story:

Think small – and think twisted.

There are good reasons why you can’t continue your short story. You could be blocked because you have too much going to on. In short, you may be writing a 5,000-word novel instead of a short story.

In a short story, you don’t need long, dreamy descriptions of the scenery.

You don’t need six subplots.

You don’t need to tell us your character’s awful childhood – unless it’s vital to the plot.

It’s a short story.

Think small.

Here’s another reason why your short story may be blocked: How many characters does it have?

If your short story has more than four major characters – you may — accent on may –have too many. It’s like being in a small room with too many people. You can’t move.

The short story is a small world.

Don’t make work for yourself. Giving all those people something to do is hard labor. Think small. Cut back on your characters.

If your story is going nowhere, consider some pruning. Clear out all the extraneous details, the unnecessary characters, the descriptions of the weather.

If you’re still not sure, read the story out loud. Read it to your spouse, or your dog, or your wall. But tell the story instead of looking at it on the page.

That’s a good way to find out what works – and what doesn’t.

Lawrence Block is a master of the traditional short story.

Let me show you what he does in one paragraph – one – in a short story called “This Crazy Business of Ours.” It’s in Block’s anthology called Enough Rope. If you’re interested in traditional short stories, I recommend this anthology.

“This Crazy Business of Ours”

“This Crazy Business of Ours”

The elevator, swift and silent as a garrote, whisked the young man eighteen stories skyward to Wilson Colliard’s penthouse. The doors opened to reveal Colliard himself. He wore a cashmere smoking jacket the color of vintage port. His flannel slacks and broadcloth shirt were a matching oyster white. They could have been chosen to match his hair, which had been expensively barbered in a leonine mane. His eyes, beneath sharply defined white brows, were as blue and as bottomless as the Caribbean, upon the shores of which he had acquired this radiant tan. He wore doeskin slippers upon his small feet and a smile upon his thinnish lips, and in his right hands he held an automatic pistol of German origin, the precise manufacturer and caliber of which need not concern us.

See how Block establishes a character in one paragraph? That is true economy of writing.

Make sure your story is about what it’s about. In a novel, you don’t have to get to the story right away. You have time to develop it. Time to build. Slowly.

In a short story, you have to hit them and run.

This is one of my favorite short story leads. It’s by Maria Lima in the Chesapeake Chapter Sisters in Crime anthology called Chesapeake Crimes I. Here it is:

“The telegram said it all: AUNT DEAD. STOP. BUTLER DID IT. STOP. FLY SOONEST. STOP. GERALD.”

That’s short and to the point. The writer has hooked you and she’s ready to move on to the story.

That takes me to the second requirement of a good short story. It needs a twist. It needs a surprise – either in the beginning or the end. But get that surprise in there.

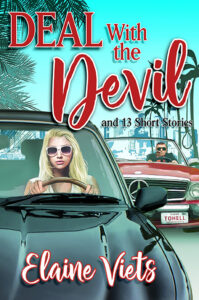

Here’s the lead to my short story, “Red Meat,” which was nominated for an Agatha and a Macavity. It was in Blood on their Hands edited by Lawrence Block, and now in my own anthology, Deal with the Devil and 13 Short Stories.

“Ashley has a body to die for, and I should know. I’m on death row because of her.

“You want to know the funny thing?

“My wife bought me Ashley. For a present.”

There’s your twist – in three sentences.

Maybe your short story has all those things, but so what? It still feels lifeless.

You can’t make it get up and walk. You need something to liven it up. Ask yourself what specialized knowledge you have that could make your short story unique, and then build the story around it.

I was asked to write a short story for a gambling anthology. I panicked. I was going to tell my editors no. I don’t know how to gamble. I don’t play poker or blackjack. What am I doing in a gambling anthology?

Then I realized I did know gambling. My aunts used to take me to bingo. I was brought up Catholic – and I learned how people can cheat at bingo, and especially, how they can cheat at cruise ship bingo. Do you know what the prize is for cruise ship bingo?

Twenty thousand dollars on some cruises. That’s major money. That’s big-time gambling. Bingo! I had a short story.

The result was “Sex and Bingo,” which was nominated for an Agatha Award.

At a short story seminar in New York, I heard top editors talk about what made a good short story, what they buy, and what they won’t buy.

Here are some things editors DO NOT want:

– No more stories about husbands who kill wives, or vice versa.

– No more stories about husbands who kill wives, or vice versa.

– No more stories ending, “And then I woke up.”

What do they want?

A fresh voice.

An unusual location.

An offbeat character.

An opening that grabs them.

That was the most important part. You have one sentence – maybe two – to catch an editor’s eye with a short story.

Make every word count.

***

Elaine Viets was nominated for a 2021 International Thriller Award for her short story: “Dog Eat Dog” in The Beat of Black Wings, edited by Josh Pacher. Crippen & Landru has published Elaine’s own collection, Deal with the Devil and 13 Short Stories Stories. Buy it here: https://www.amazon.com/Deal-Devil-Elaine-Viets/dp/1936363275