So here I am typing with seven fingers, and one thumb for spacing.

I’m sure we all type differently. Some with only index fingers, while others might utilize more digits as they watch the keys. There’s the “hunt and peck” crowd, and then those of us who were taught to touch type without looking at the keyboard.

That’s where I fall in. I never look at my fingers or the letters, only the words that appear on the screen, at least until three weeks ago when my orthopedic physician diagnosed a partially torn ligament in my left middle finger. That injured digit is now strapped securely to its index neighbor, requiring me to watch my left hand hunt and peck.

Being longer than the rest, the middle finger hamstrings my index digit, which should be striking the letters b, f, g, r, and t. Mr. Middle often misses c, d, e and because I can’t find the home keys, there are many, many typos.

Thanks to my lucky stars I can delete and backspace with my right, which I do on nearly every other word. If I was using real paper and White-Out, I’d be buying both by the train load.

for example, rhis is whar it looks lik4 qhen I’m nor warchinfg my gands.

This current malady throws off my writing balance on the other hand, causing it to make mistakes. And to make things worse, I just today sliced the end of my right middle finger and that bandage is also causing problems.

Irritating ain’t no word for it, and I have a self-imposed book deadline by the end of this month.

To make things worse, I had to visit my regular doctor to get a reference to the ortho.

“So, what brings you in today” The masked physician’s assistant settled down in front of her laptop resting on the exam room’s counter. In days gone by, those counters held a variety of torture instruments utilized by doctors who actually came into the examination room.

“Like I told the lady on the phone when I made the appointment, and by the way, she asked a lot of questions, anyway, I tripped while the Bride and I were hiking in Sedona and she says I fell like a redwood. I think I fractured my left middle finger.”

I resisted the urge to hold it up to her, fearing she’d take the familiar gesture the wrong way.

She hammered her keyboard with all fingers. “Which one?”

And that question brings me to my biggest pet peeve, besides this injured digit. No one listens anymore, because everyone is on some kind of device when they should be paying attention. Whether it’s the local fast food drive-through, which invariably gets my order wrong, to the kids bagging groceries, to the doctor’s office and an exam I didn’t need.

Through six decades of work and play, I’ve jammed, fractured, dislocated, cut, and broken almost all my fingers, except for the one in question. I waited for over six weeks after this particular injury for the swelling to go down, but it remained puffy. By the time I called the doctor’s office, it was stiff and painful in the mornings and I couldn’t curl it any longer.

The truth was, I wanted a specialist, but my GP said he had to see me (read here, his nurse practitioner) before he would recommend anyone and the others I called directly required a reference.

So Nurse Calpurnia sat at her computer and typed while I related the events leading up to that moment. “So anyway, that’s what happened.” I waited while Nurse Calpurnia squinted at her screen, apparently typing her own novel with two fingers. “And now I’m typing with nine fingers.”

She paused and considered my statement. “You only have eight fingers and two thumbs.”

“Oh, we’re going there, huh? Okay, I type with everything except for my left thumb, which just hangs there for balance I guess, kinda like an outrigger, and strangely, it doesn’t get tired after an entire day of working on my novel.”

She addressed the screen, distracted. “So it’s just your middle finger.”

I wanted to hold it up at her, but she wouldn’t have seen it anyway. “Yes. I wish I’d jammed my left thumb instead.”

“Why?”

I was succinct in my presentation, so what did she miss? I had to blink at that question for a moment, something she didn’t notice, either, because she was still hammering away on her keyboard.

Maybe she wants to be a novelist, and takes some kind of mysterious keyboard shorthand to get all the details, and then while patients are talking, she can write two or three paragraphs on her manuscript. At the end of any given day, Nurse Calpurnia could be five or six pages further along toward finishing. I think that’s kinda brilliant.

She pulled me from my reverie. “So you’re healthy otherwise.”

“Well, my knee’s still a little sore, but I’m not here for that. I’ll come back later if it keeps hurting so we can go through this again when I need a knee specialist.”

She missed my sarcasm. “Let me see your finger.”

And once again, I resisted the urge to demonstrate a proper gesture. She studied the extremity for a moment. “Let me see your other hand for comparison.”

“It looks a lot like my left, but without the swollen finger.”

“Does it hurt?”

“Not really.”

“On a scale of one to ten?”

“One.” Instead of striking three letters, she typed for about five minutes, likely finishing a conversation between her characters.

“I can type really fast.” I decided to interrupt her train of thought. “Some days I’ve knocked out over 5,000 words, and once, I wrote 14,000. Now I’m down to 2,000 on a good day, because I taped this one to my index finger for support.” I paused to let that sink in, since she was still working on her book.

She finally straightened, cracked her knuckles, and frowned at me. “Why’d you wait six weeks before coming in?”

“I expected the swelling to go down.”

“But it hasn’t.”

“No.”

We nodded at each other and smiled, glad to have come to some sort of understanding.

“I need to take your blood pressure, pulse ox, and listen to your lungs.”

“They’re fine. I was in a month ago for a physical and all the pokes and listening and prods and blood work said I’m healthy.”

“Things can change.” She performed those duties as assigned and sat back down and attacked her keyboard long enough to finish a chapter. “Looks good.”

I wasn’t sure if she was talking about her book, or my exam results. “All except for my crooked finger.”

“It doesn’t look all that straight, does it?”

“That’s why I’m here.”

“Have you taken anything for it?”

“Gin.”

“Excuse me?”

“Well, aspirin, but I’m an author and we drink…some…because I think it’s a law or we’re contractually obligated, so a few gin and tonics to chase a handful of aspirin and I’m good until the next day.”

“Fine, well, it looks like I need to send you for an X-ray.”

“That’s why I’m here, so I can get in to see an orthopedic.”

“We don’t do that here.”

“I know. I’m going through the process that would have been quicker if the doctor’d just given me a referral.”

“He can’t do that until he sees you.”

“Will he be in?”

“Not for something like this. I just made you an appointment for an X-ray at the imaging center.”

“When did you do that? You haven’t touched the keyboard since you finished that last chapter.”

“It was rather long, wasn’t it?”

“Everyone wants to be an author.”

“We all have our goals.” She closed her laptop and left.

So here I am, fingers still strapped together and typing 4,000 words a day, but backspacing over half of them because they’re typos. I really wanted to finish this novel by the end of the month, but that’s not happening. I’m shooting for October 1, with 30,000 words to go, which equates to 60,000 strokes plus revisions…

…I’m gonna quit now. It’s too depressing.

Deep down each of us have a strong but underused connection to the world around us.

Deep down each of us have a strong but underused connection to the world around us.

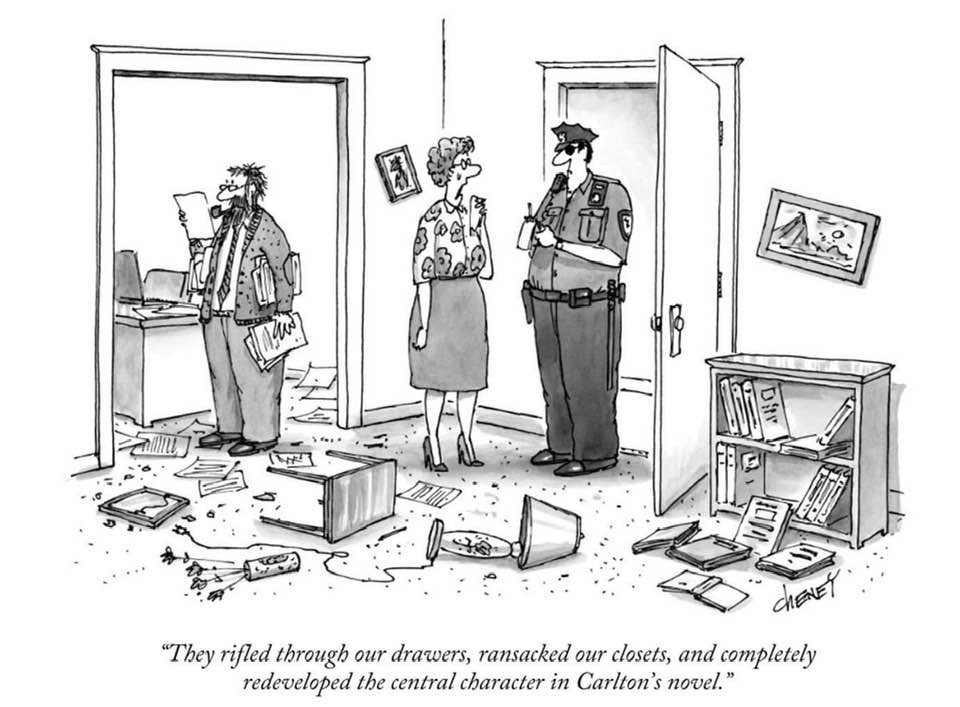

It is my great pleasure today to do my part to bring us closer to a modicum of peace between two vexatious parties. No, not those parties. I’m talking about the Hatfields and Mc…wait, I mean the plotters and the pantsers. For I am about to offer a systematic approach to beginning a novel that has the potential to do what we all aim for—sell like dang hotcakes!

It is my great pleasure today to do my part to bring us closer to a modicum of peace between two vexatious parties. No, not those parties. I’m talking about the Hatfields and Mc…wait, I mean the plotters and the pantsers. For I am about to offer a systematic approach to beginning a novel that has the potential to do what we all aim for—sell like dang hotcakes!