by Debbie Burke

A good title and cover can make a book. A bad title and cover can break a book.

That’s a lot of pressure. No wonder authors struggle so hard to get it right.

If you’re with a traditional press, those decisions are usually made by the publisher.

But, if you’re an indie author, the task of both title and cover fall on YOU.

Are you cracking under the weight of those responsibilities? I know I am so I checked the TKZ Library for guidance.

Several TKZers have posts about revamping covers after getting their rights back from the original publisher. Please check out the excellent information shared by Jordan Dane, P.J. Parrish, and Laura Benedict.

TKZ emeritus Nancy J. Cohen explores how to use covers to establish a brand.

Jim Bell offers invaluable advice on choosing a title.

With my fourth book coming out this summer, right now I’m deep into working on title choice and cover creation. I want to share the steps I’ve taken, not because I’m an expert, but because they demonstrate the mysterious, murky process of creative evolution.

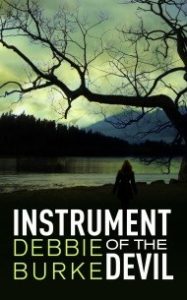

My first book in the series, Instrument of the Devil, was traditionally published. They retained my title but nixed my cover idea. They offered several redesigns and, with my approval, decided on this:

I wasn’t in love with it but, hey, they paid me so they’re the boss.

Then, six months after publication, they shut down operations and I became an orphan.

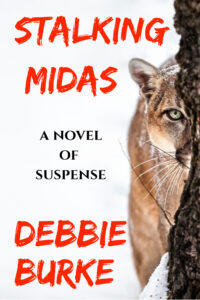

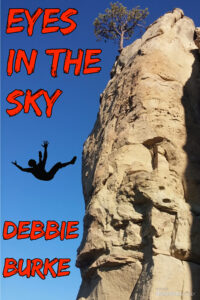

I decided to go indie and published the second book, Stalking Midas, in August, 2019, and the third, Eyes in the Sky, in January, 2020.

Publishing those two books taught me a lot but there were more lessons to be learned while wrestling with the unruly gorilla that was book #4.

Here’s a quick story summary:

Investigator Tawny Lindholm’s plans for a romantic Florida vacation with attorney Tillman Rosenbaum vanish when they’re caught up in Hurricane Irma. Tillman’s beloved high school coach, Smoky Lido, disappears into the storm, along with a priceless baseball card. Is he dead or on the run from a shady sports memorabilia dealer with a murderous grudge? During a desperate search in snake-infested floodwaters, Tawny becomes the bargaining chip in a high-stakes gamble. The winner lives, the loser dies.

Here are the realizations and steps along the twisty paths I followed to find a title and cover:

#1: I can’t do it alone.

The author is too close to the story, too enmeshed with the subplots, relationships, and minute details. Objectivity and distance are close to impossible to achieve.

Fortunately, I’m surrounded by a smart, supportive community of writers. They provide that much-needed objectivity and distance.

First, I asked the gang for title ideas.

The working title was Lost in Irma, because the story is set in Florida during the 2017 hurricane that knocked out power to millions of people.

Lost in Irma was lame so I tried variations like Flight into Irma, Escape from Irma. Finally, a member of my critique group pointed out an obvious reason that “Irma” would never work for a thriller—it brings to mind the legendary humorist, Erma Bombeck. Well, duh, why didn’t I realize that? Because I lacked objectivity.

A title needs to convey the genre, main plot, subplots, and themes, all in a few select words. Pretty overwhelming, right? Let’s break the elements down, piece by piece, and see if any of them trigger ideas.

The genre is thriller. The main plot is the search for the missing man, Smoky. Subplots include difficulties caused by the hurricane, including power outages and cell phones that don’t work; gambling addiction; baseball; the troubled relationship between Tawny and Tillman; a teenager trying to teach her rambunctious pup how to be a search dog. The themes are friendship, loyalty and betrayal.

Now, how to combine them into a title?

Another critique buddy, an attorney, specializes in laser focus. She said: “Somehow you should convey there is a mystery to be solved and it happens in the middle of a hurricane.”

#2: Get out of the corner.

A five-day-long power outage underscored much of the story, resulting in these title ideas: The Long Darkness, Flight into Darkness, Time of Darkness.

Sometimes the mind gets stuck, fixated on a single idea, even if it’s a bad idea. I felt like a Roomba, trapped in a corner, bouncing off the same two walls, getting nowhere.

Another critique pal pointed out, while darkness is important to the story, it’s not relevant enough to include in the title.

She kicked my mental Roomba out of that corner and sent me in new directions.

More tries: Presumed Dead, Gamble in Paradise, No Escape. Still not there.

The McGuffin is a valuable stolen baseball card and another suggestion was to use the baseball motif: Foul Pitch, Curveball, Pinch Hitter. Still not there.

Another suggested using pivotal plot events, like the discovery of Smoky’s deserted, wrecked boat and the gruesome evidence the dog finds in the swamp. Those ideas didn’t yield good titles but merited consideration for cover art, described in #5 and #6 below.

#3: Many Brains are Better Than One.

Creativity feeds off imagination. The more imaginations at work, the more creativity thrives. It’s like shaking a bottle of carbonated beverage. Open that cap and watch what bubbles up.

My smart friends stimulated my imagination with their varied ideas. At last, a title bubbled up that says thriller and suggests the root of Smoky’s problems—gambling.

Dead Man’s Bluff

For now, I’m pleased with that unless something better comes along.

~~~

Finding the right cover image is every bit as hard as finding the right title.

Many authors hire a professional designer and that is often the wisest path. My experience with pros has been expensive and unsatisfying but that isn’t always the case. If I find an artist who’s the right match, great. For now, it’s DIY.

#4: The Author Can’t See the Obvious

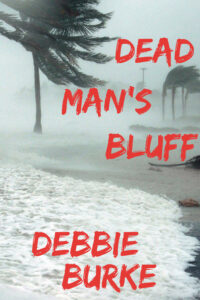

I searched for images of Hurricane Irma. Here’s an early choice I sent to my critique group:

Several immediately shot back: “That looks like a breast with a nipple.” Just shows how blind an author can be, even when it’s right in front of her nose!

#5: Don’t Be Afraid to Experiment

There’s a lot of trial and error in this creative process. You need to learn what doesn’t work before you can recognize what does. Most experiments aren’t great.

Tried a color version here.

A bright, eye-catching picture but it did nothing to draw reader into the story. It was also too busy and hard to read.

Next, I searched for images with people or objects tied to important plot developments.

After Smoky disappears, Tawny and Tillman find his wrecked boat, indicating he might have drowned while trying to make a getaway by sea. This photo seemed promising.

#6: People are Happy to Help

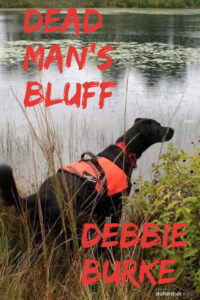

A subplot involves a Lab pup in training to be a search dog. He eagerly plunges into the swamp to search for the missing Smoky. Although he finds crucial evidence, he also screws it up, adding more complications to the story.

The dog angle became another avenue to explore. A friend put out a call to Search and Rescue (SAR) colleagues for photos of a dog working in water. SAR responded with many great pictures. These good folks were happy to help out a complete stranger. They didn’t even want payment. If I used their photos, their only request was acknowledgement of the SAR group, the dog, and the handler.

Here are a few dog samples:

#7: Don’t Let Your Cover Mislead the Reader

I drafted several covers with dogs and sent them to the group. One woman made the astute observation that having a dog on the cover sent the message that it’s a dog story. She was dead on—while the subplot is important, it isn’t the main focus.

A cover shouldn’t mislead readers. If you raise their expectations for one type of book but it turns out to be another, they rightfully feel cheated.

Fortunately, that same woman sent a hurricane photo that caused bells to ring in my mind. More on that in a minute.

#8: Ask an Artist

Another writer pal is a gifted watercolor artist with an excellent eye. I sent her three samples. She patiently explained what worked and what didn’t and why.

The colorful wave and boat: “An image directly in the center of the frame is not as appealing as one off center; the imbalance creates a sense of movement or dynamics that a centered image does not.”

She liked the offset title of the dog cover. However, the dog wasn’t a good choice as discussed in #7 above.

The windswept beach: “A Left to Right orientation appeals to me better than the R to L orientation on the shore design.”

So, I flipped the photo to a mirror image of the original. Now the palm trees blew to the right. That required cropping a different area of the photo and rearranging the lettering. Yet, one subtle change of orientation made a big difference.

Then I remembered a different artist had made a similar suggestion about my third book, Eyes in the Sky. In the original photo, the cliff was to the left. She suggested flipping the image to put the cliff on the right to make it consistent with the design of the second book, Stalking Midas. Again, the objective outsider’s view looked past the author’s tunnel vision for a better solution.

Artists notice small details like photo orientation that authors may not. That might make the difference between a reader choosing your book or passing it by.

#9: Enlist a Focus Group

Once you have three or four polished contenders for cover finalists, it’s time to attract cold readers. How do you capture the interest of someone browsing in a bookstore (hope they reopen soon!) or scanning thumbnails of covers online?

Find a focus group. But how?

Seek out reading groups on social media. Become active and contribute to discussions in your genre. Then politely ask for their help. Post several sample covers and take a vote. Even better, connect the voting to a drawing for a free book when it’s published.

Locate avid readers among your friends, coworkers, neighbors, acquaintances from the gym, clubs, churches or temples, librarians, your kids’ teachers—anyone who loves to read.

Book clubs have been great supporters of my previous three books and are an ideal focus group. I sent emails to more than forty people with a brief plot summary and three sample covers–the boat, the dog, and the windswept beach–and asked them to vote for their favorite.

Votes came in overwhelmingly for the wind-swept palm trees on the beach—the same photo that had set off bells in my head. Their opinions confirmed my intuition that this hurricane photo captured the right mood and tone that accurately depicted the book.

An added benefit: the book club folks enjoyed being part of the creative process. “I love voting on the choices,” wrote one. Another said, “This is fun.” Several asked to be notified which cover won. I benefited from their valuable feedback and they’re eagerly anticipating the next book in the series. Win-win.

When people play a part in the mysterious, creative process of building a book, they become invested in the outcome.

Interested, engaged readers are treasures to an author.

#10: Embrace New Ideas. At this point, I’m satisfied the title and cover do a good job of conveying the genre, mood, and plot. But better ideas might still come along…maybe even from TKZers’ comments!

During the creative process, an author should remain open to suggestions, especially from readers. You don’t have to take them but always listen.

Control and autonomy are two major benefits of self-publishing. An indie author isn’t locked into anything until s/he hits the “Publish” button.

~~~

This sums up my process through the evolution of title and cover. When Dead Man’s Bluff is published this summer, readers will have the final vote.

The creative process is mysterious and highly individual. What I find helpful, you might find useless. There are no right or wrong ways, only ways that work for you.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how you start the evolution as long as you start it.

Get ideas flowing, no matter where they come from. What starts as a trickle may turn into a torrent that carries you to your goal.

~~~

TKZers: What makes a book cover appeal to you?

Do you have a system for choosing titles and/or cover designs?

~~~

To read a sneak preview of Dead Man’s Bluff, visit this link.