Social Media, Blogging, and SEO Tips

To prepare for my first post as a TKZ member (yay!), I read all the social media posts on the Kill Zone (my little research addiction rearing its head :-)). Back as far as 2009, Joe Moore wrote Social Networking Showdown, which explored MySpace vs. Facebook, Shelfari vs. Goodreads, Crimespace, Gather, Bebo, LinkedIn, and the all-important email list. Even though some of these sites are nonexistent today, Joe’s advice still applies. And in 2011, he shared his perspective on using manners online. Which is critical these days.

To prepare for my first post as a TKZ member (yay!), I read all the social media posts on the Kill Zone (my little research addiction rearing its head :-)). Back as far as 2009, Joe Moore wrote Social Networking Showdown, which explored MySpace vs. Facebook, Shelfari vs. Goodreads, Crimespace, Gather, Bebo, LinkedIn, and the all-important email list. Even though some of these sites are nonexistent today, Joe’s advice still applies. And in 2011, he shared his perspective on using manners online. Which is critical these days.

The way we conduct ourselves on social media matters. Hence, why Jim made social media easy and why, I presume, Jodie Renner invited Anne Allen to give us 15 Do’s and Don’ts of social media as only Anne could, with her fantastic wit.

One year later, in 2016, Clare shared what’s acceptable for authors on social media and what isn’t. Jim showed us the dangers of social media, and how it can consume us if we’re not careful.

Through the years the Kill Zone authors have tried to keep us from falling into the honey trap of social media. Which brings me to the burning question Kathryn posed this past June: Writers on Social Media: Does it Even Make a Difference?

In my opinion, the correct answer is yes.

Working writers in the digital age need to have a social media presence. Fans expect to find a way to connect with their favorite author. How many of you have finished reading a thriller that blew you away, and immediately went online to find out more about the author? I know I have. It’s only natural to become curious about the authors whose books we love. Give your fans a way to find you — the first step in building an audience.

I’ve seen authors who don’t even have a website, never mind an updated blog. This is a huge mistake, IMO. It’s imperative to have a home base. Without one, we’re limiting our ability to grow.

BLOGGING

There are two types of blogging: those who blog about their daily routine and those who offer valuable content. Although both ways technically “engage” our audience, the latter is a more effective way to build and nurture a fan base.

When I first started blogging I had no idea what to do. I got in contact with a web design company (just like web design company Nashville) to help me get set up, and away I went! I’ve always loved to research, so I used my blog as a way to share the interesting tidbits I’d learned along the way. For me, it was a no-brainer. I’d already done the research. Writing about what I’d learned helped me to remember what I needed for my WIP while offering valuable content to writers who despise research (Gasp!). Over time my Murder Blog grew into a crime resource blog.

Running a resource blog has its advantages and disadvantages. Be sure to look into the pros and cons before choosing this route. When I first scored a publishing deal, I realized most of my audience was made up of other writers. The question then became, how could I attract non-writers without losing what I’d built?

My solution was to widen my scope to things readers would also enjoy, like flash fiction and true crime stories. Who doesn’t like a good mystery?

With a resource blog it’s also difficult to support the writing community. Book promos go over about as well as a two-ton elephant on a rubber raft. If you decide to run a resource blog, find another way to support your fellow writers. When one of us succeeds, the literary angels rejoice.

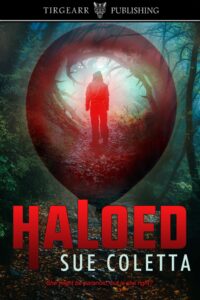

There’s one exception to the “no book promos” rule for resource blogs, and that is research. It’s always fun to read about other writers’ experiences. Subtly place their book covers somewhere in post (with buy link). That way it benefits both your audience and the author.

The one thing we can count on is that how-to blog changes with the times. A few months ago, my publisher shared a link to an article about blogging in 2018. Because she shared the article via our private group, I’m reluctant to share the link. The gist of article is, come 2018 bloggers who don’t offer some sort of video content will be left in the dust. Only time will tell if this advice holds true, but it makes sense. The younger generation loves YouTube. By adding a video series or a Facebook Live event we could expand our audience.

It’s time-consuming to create each video episode. Hence why I had several months in between the first two episodes of Serial Killer Corner. Our first priority must be writing that next book. However, consistency is key. Weekly, monthly, bi-monthly? Choose a plan that works for you and stick with it. There are many internet marketing experts who can help make your blog become successful.

SEO MATTERS

SEO — Search Engine Optimization — drives traffic to your website/blog. Without making this post 10K words long, I’m sharing a few SEO tips with added tips to expand our reach. In the future I could devote an entire post to how to maximize SEO. Would that interest you?

Tips

- every post should have at least one inbound link and two outbound links; we highly recommend speaking to a digital marketing agency such as OutreachPete.com to get guidance on how to build these links.

- send legacy blogs a pingback when linking to their site;

- never link the same words as the post title or you’ll lessen the previous posts’ SEO (note how I linked to previous TKZ posts in the 1st paragraph);

- use long-tail keywords rather than short-tail (less competition equals better traffic);

- using Yoast SEO plug-in is one of the easiest ways to optimize a blog’s SEO;

- self-hosted sites allow full control of SEO, free sites don’t;

- remove stop words in the post slug (for example, see the permalink for this post); I’d also recommend removing the date, but that’s a personal preference;

- drip marketing campaigns drive traffic to your site;

- slow blogging drives more traffic than daily blogging (for a single author site);

- consistency is key — if you post every Saturday, keep that schedule;

- use spaces before and after an em dash in blog posts (not books);

- use alt tags on every image (I use the post title, which should include the keyword); if someone pins an image, the post title travels with it;

- link images to post and book covers to buy link;

- white space is your friend; use subheadings, bullet points, and/or lists;

- longer posts (800 – 1, 000 words min.) get better SEO than than shorter ones;

- using two hashtags on Twitter garners more engagement than three or more;

- protect your site with SSL encryption (as of this month, Google warns potential visitors if your site isn’t protected; imagine how much traffic you could lose?);

- post a “SSL Protected” badge on your site; it aids in email sign-ups;

- via scroll bar or pop-up, capitalize on that traffic by asking visitors to join your community, which helps build your email list;

THE 80/20 RULE

Most of us are familiar with the 80/20 rule. 80% non-book-related content; 20% books. My average leans more toward 90/10, but that may be a personal preference.

What should we share 80% of the time? The easiest thing to do is to share what we’re passionate about. When I say post about passion I don’t mean writing. Sure, we’re all passionate about writing, but I’m sure that’s not the only thing you’re passionate about. How about animals, nature, cooking, gardening, or sports?

One of the best examples of sharing one’s passion comes from a writer pal of mine, Diana Cosby, who loves photography. Every Saturday on Facebook, she holds the Mad Bird Competition. During the week she takes photos of birds who have a penetrating glare and/or fighting stance. On Saturdays, she posts two side-by-side photos and asks her audience to vote for their favorite “mad bird.” Much like boxing, the champion from that round goes up against a new bird the following week.

On Fridays, she posts formal rejection letters to birds who didn’t make the cut. With her permission, here’s an example:

Dear Mr. House Sparrow,

I regret to inform you that though your ‘fierce look’ holds merit, it far from meets the requirements for entry into the Mad Bird Competition. Please practice your mad looks and resubmit.

Sincerely,

M.R. Grackle

1st inductee into the Mad Bird Hall of Fame

It’s a blast! I look forward to these posts every week. As such, I’m curious about her books. See how that works?

My own social media tends to run a bit darker … murder & serial killers top the list, but I also share stories about Poe & Edgar, my pet crows who live free, as well as my love for nature and anything with fur or feathers. The key is to be real. Don’t try to fake being genuine. People see right through a false facade. Also, please don’t rant about book reviews, rejection letters, or anything else. Social media is not the place to share your frustrations.

As for soft marketing on social media, I like to make my own memes. It only takes a few minutes and it’s a great way to keep your fans updated on what you’re working on. In the following example I wrote: #amwriting Book 3, Grafton Series. I also linked to the series. Don’t forget to include a link to your website. The more the meme is shared, the more people see your name. Keep it small and unobtrusive. See mine in the lower-right corner?

In the next example, I asked, “What’s everyone doing this weekend? No words, only gifs.” Have fun on social media. The point is to engage your audience.

Folks love to be included. Plus, I genuinely want to get to know the people who follow/friend me. Don’t you? It doesn’t take much effort to make your fans feel special. Take a few moments to mingle with them. It’s five or ten minutes out of your busy schedule, yet it may be the only thing that brightens someone’s day. In a world with so much negatively and hatred, be better, be more than, be the best person you can be … in life and on social media.

Over to you TKZers. How do you approach social media?

Last week, Sisters in Crime approached me to do a

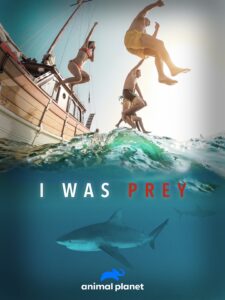

Last week, Sisters in Crime approached me to do a  In story terms, a villain is a person, entity, or force who is cruel, evil, or malicious enough to wish the protagonist harm. Rather than simply blocking a goal or interfering with the hero’s plan, a villain causes suffering, making it vital for them to be conquered by the protagonist. Clarice must find and defeat Buffalo Bill if she wants to rise above her past and become a great FBI agent (

In story terms, a villain is a person, entity, or force who is cruel, evil, or malicious enough to wish the protagonist harm. Rather than simply blocking a goal or interfering with the hero’s plan, a villain causes suffering, making it vital for them to be conquered by the protagonist. Clarice must find and defeat Buffalo Bill if she wants to rise above her past and become a great FBI agent ( Like the hero, the villain has an overall objective, and they’re willing to do anything within their moral code to achieve it. When their goal is diametrically opposed to the hero’s, the two become enemies in a situation where only one can succeed.

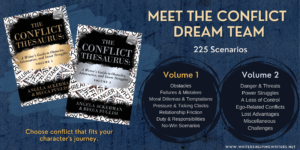

Like the hero, the villain has an overall objective, and they’re willing to do anything within their moral code to achieve it. When their goal is diametrically opposed to the hero’s, the two become enemies in a situation where only one can succeed.  Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers. Her books have sold over 900,000 copies and are available in multiple languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world. She is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge with others through her

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers. Her books have sold over 900,000 copies and are available in multiple languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world. She is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge with others through her  If I transported you into the current book you’re writing or reading…

If I transported you into the current book you’re writing or reading… Deep down each of us have a strong but underused connection to the world around us.

Deep down each of us have a strong but underused connection to the world around us.

Goals are important. Goals keep us on track and moving forward.

Goals are important. Goals keep us on track and moving forward. Please excuse my absence over the last 7-10 days while I was on deadline. I’m usually a better multitasker. *sigh*

Please excuse my absence over the last 7-10 days while I was on deadline. I’m usually a better multitasker. *sigh*