Let’s say you’ve got a character in your story who had no background in firearms, yet needs to engage an armed bad guy. A shotgun may be your character’s best choice, especially at close quarters. Because every pull of the trigger sends multiple high-velocity projectiles downrange simultaneously, marksmanship is less of an issue when it comes to killing the enemy, but more of an issue when it comes to shooting only the enemy.

In previous posts, I’ve talked about rifles and pistols, so this week, I thought I’d devote some time to shotguns. As a first step, forget much of what you’ve learned about rifles and pistols. The rules of Newtonian physics all remain the same, but much of the terminology seems counter-intuitive when you deal with smooth-bore weapons.

Okay, what’s a smooth-bore weapon?

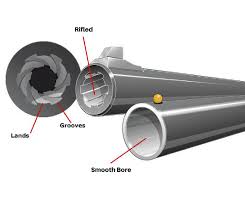

Whereas modern rifles and pistols fire bullets, shotguns fire either pellets or slugs. As a bullet is propelled down a rifle’s barrel, the lands and grooves that have been cut into the metal to form “rifling” impart a spin on the projectile that stabilizes it in flight and allows for greater range and accuracy. Standard shotguns, on the other hand, have no rifling down the bore. The barrel is simply a smooth tube. (Note: there is such a thing as a rifled shotgun, but I won’t be addressing that here.) Basically, a smooth-bore barrel is merely an extended pressure vessel that allows the projectile(s) to accelerate.

Whereas modern rifles and pistols fire bullets, shotguns fire either pellets or slugs. As a bullet is propelled down a rifle’s barrel, the lands and grooves that have been cut into the metal to form “rifling” impart a spin on the projectile that stabilizes it in flight and allows for greater range and accuracy. Standard shotguns, on the other hand, have no rifling down the bore. The barrel is simply a smooth tube. (Note: there is such a thing as a rifled shotgun, but I won’t be addressing that here.) Basically, a smooth-bore barrel is merely an extended pressure vessel that allows the projectile(s) to accelerate.

Think gauge, not caliber. Think spheres, not bullet-shaped.

It’s common to refer to rifles and pistols by the diameter of the bullets they fire. A “.30 caliber” rifle fires a bullet that is three-tenths (.30) of an inch in diameter at its widest point. A “.45” fires a bullet that is 45/100ths of an inch at its widest point.

Shotguns, on the other hand, are referred to by their “gauge” and the term has nothing to do with linear measurement. To understand the reason why, we need to geek out a little:

One characteristic of elemental lead is that when melted, its physical volume is a constant, relative to it’s weight. Thus, a one-pound sphere of lead will always be 1.66 inches in diameter (assuming I did the math correctly). From the days of the Napoleonic Wars through the American Civil War and beyond, one of the primary artillery cannons was the “twelve-pounder”, which, predictably, I suppose, fired a twelve-pound ball (also called a “shot”–as in the shot put event in track-and-field, get it?) out of a barrel that was 4.62 inches in diameter.

The concept of “gauge” is based on the same principle, but in this case dealing with fractions of a pound. The bore of a 12 gauge shotgun is the diameter of a lead sphere that weighs 1/12 of a pound, or 0.727 inches. A 20 gauge shotgun has a bore of 0.617 inches, which is the diameter of a lead sphere that weighs 1/20 of a pound.

Still with me?

One of the most counter-intuitive parts of discussing shotguns is the fact that unlike calibers, higher gauges actually mean smaller projectiles.

Buckshot, Birdshot, Slugs.

So, we’ve got our smooth-bore shotgun of a chosen gauge–for our purposes here, we’ll assume 12 gauge if only because it the most common shotgun deployed by law enforcement officers. The size of the bore is largely just a reference point; it has little to do with the weight of the projectile being sent downrange.

So, we’ve got our smooth-bore shotgun of a chosen gauge–for our purposes here, we’ll assume 12 gauge if only because it the most common shotgun deployed by law enforcement officers. The size of the bore is largely just a reference point; it has little to do with the weight of the projectile being sent downrange.

One of the strengths of a shotgun as a weapon platform is its versatility. The same gun can be used to hunt doves and deer, and then when you come home, it can be a great home defense weapon. Different applications require different ammunition, though, and here’s where things get complicated again.

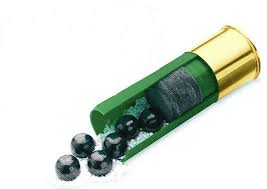

Starting with the basics, each round of ammunition is called a “shell”, not a “bullet” or a “cartridge”, as would be case with rifle and pistol ammo. Inside the shell, the pellets (or “shot”) are separated from the propellant (or “powder”) by a plastic cup that is call the “wad.” Each pull of the trigger sends a “load of shot” or a “slug” downrange. Once spent, the “hull” is ejected.

Starting with the basics, each round of ammunition is called a “shell”, not a “bullet” or a “cartridge”, as would be case with rifle and pistol ammo. Inside the shell, the pellets (or “shot”) are separated from the propellant (or “powder”) by a plastic cup that is call the “wad.” Each pull of the trigger sends a “load of shot” or a “slug” downrange. Once spent, the “hull” is ejected.

When the load reaches the muzzle on its way downrange, the pellets are tightly grouped together, but as they travel through the air, they separate to form a spray of projectiles. The width of the spread and the terminal performance of individual projectiles has everything to do with their size and their weight. “Birdshot” refers to smaller, lighter pellets that are designed to kill smaller, lighter prey. “Buckshot”, on the other hand, is designed for larger prey. Within, say, 10 feet, both are equally lethal.

When the load reaches the muzzle on its way downrange, the pellets are tightly grouped together, but as they travel through the air, they separate to form a spray of projectiles. The width of the spread and the terminal performance of individual projectiles has everything to do with their size and their weight. “Birdshot” refers to smaller, lighter pellets that are designed to kill smaller, lighter prey. “Buckshot”, on the other hand, is designed for larger prey. Within, say, 10 feet, both are equally lethal.

Here again, smaller is bigger. The size of individual pellets is described by industry-accepted numbers. On paper, you might read “#4 buck”, but you would pronounce it as “number four buck.” And #4 buck is smaller than #3 buck.

What most people think of when they’re talking about buckshot is #00 buck, which is commonly referred to as “double aught buck.” (Note: It’s NOT double ought.) Individual pellets are 0.33 inches in diameter (.33 caliber) and there are nine of them in an ounce. By contrast, #4 buck pellets are 0.24 inches in diameter (24 caliber) and there are 24 of them in an ounce.

Bird shot is also categorized by numbers, but on a different scale. For example, No. 4 bird shot pellets are 0.13 inches in diameter, and there are 135 of them in an ounce.

A slug is a single projectile that essentially turns the shotgun into a less accurate rifle and hits with enormous force. Slugs come in many different forms and perform many different functions. For example, when you hear of riots being dispersed by the use of “rubber bullets”, those “bullets” are really rubber slugs, or sometimes beanbag slugs.

Types of Shotguns.

Double barrel shotguns have been around for a very long time, back to the days of the flintlock. The classic arrangement for the barrels was “side-by-side”, as characterized by bird hunters and stage coach security guys. You know that’s where the phrase “riding shotgun” originated, right?

Double barrel shotguns have been around for a very long time, back to the days of the flintlock. The classic arrangement for the barrels was “side-by-side”, as characterized by bird hunters and stage coach security guys. You know that’s where the phrase “riding shotgun” originated, right?

The second configuration of a double-barrel shotgun is the “over and under” configuration, where the barrels are stacked. As a bit of trivia, you’ll note that there’s only one trigger on the gun. The act of closing the breech cocks the gun. The lower barrel shoots first and the recoil re-cocks the gun so the top barrel will fire.

Semi-automatic. As with its rifle counterpart, you can load the magazine to whatever its capacity may be, and every pull of the trigger sends a new load downrange until the magazine is empty.

Pump-action. This is the mainstay of cop shows and sound effects crews. Also called a “shucker”, this configuration requires the shooter to work the pump to eject one hull and put the next shell into battery.

Pump-action. This is the mainstay of cop shows and sound effects crews. Also called a “shucker”, this configuration requires the shooter to work the pump to eject one hull and put the next shell into battery.

So, there you have it, TKZers, this quarter’s offering of gun porn. All questions, comments and observations are welcome.

In a recent chat with Jordan, she mentioned that when she went for her TSA pre-check ID

In a recent chat with Jordan, she mentioned that when she went for her TSA pre-check ID

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar.

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar. No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else.

No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else. Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems.

Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems.