by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Earlier this year I spent three days at Disneyland with the fam, including the two grandboys, ages 4 and 2. Let me tell you, it may be the happiest place on Earth, but for three days it’s also an endurance test. My daughter told me, via her FitBit, that we averaged 21,000 steps each day. My dogs were screaming for mercy.

Earlier this year I spent three days at Disneyland with the fam, including the two grandboys, ages 4 and 2. Let me tell you, it may be the happiest place on Earth, but for three days it’s also an endurance test. My daughter told me, via her FitBit, that we averaged 21,000 steps each day. My dogs were screaming for mercy.

But we had a stupendous time. I mean, how can you not when you experience the park through the wide-eyed wonder of two small boys?

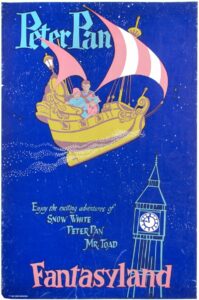

In Fantasyland there are five indoor rides within close proximity of each other. The most popular is Peter Pan. There’s always a long wait to get into this one. Right across the way are two rides for which there is virtually no wait time: Snow White and Pinocchio.

So as I waited in the Peter Pan line, I wondered, Why should this be?

I have some theories. For one thing, Peter Pan seems the most magical because you’re whisked away in a pirate ship to go flying through the sky—over Victorian London and then Never Never Land itself. There’s just something about flying that every kid loves.

Yet why should poor Snow White and Pinocchio be so lonely? There might be one reason parents don’t take their little ones on these rides—they’re scary!

I mean, in Snow White, there’s a sudden turn from happy dwarfs and singing birds to a frightening old crone who turns on you holding out a poisoned apple. From there it gets even darker, with thunder and lightning, and the crone appearing at the top of the hill wanting to smash you and the seven dwarfs with a big rock! (Confession: I recall going on this ride when I was little, with my big brother, and I was terrified.)

Pinocchio has more of a house of horrors type of scare. Pinocchio and Lampwick are taken to Pleasure Island where they smoke cigars, play pool and such. But as a consequence they are turned into donkeys. That’s not all. Just around the corner a giant whale jumps out at you, jaws agape! Sure, you end up safely back in Geppetto’s workshop, but it was one hairy journey to get there.

So I wonder if concerned parents simply don’t want their younger children to be frightened. I also wonder if that might be an opportunity lost. For fairy tales don’t exist in a vacuum. They are meant to be didactic. As G. K. Chesterton observed:

Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. (Tremendous Trifles)

Which invites the question: is great fiction always moral? We know there’s plenty of darkness swirling around, especially since anyone can upload a book or video. But is it “art” to wallow in the darkness?

The respected editor Dave King mused about this at Writer Unboxed:

Why are so many gifted writers drawn to the dark side of life? Why are they driven to present characters who are hard to love or lovable characters in situations that are either hard to follow or hard to endure? Why does it feel like work to read them? And why are they winning awards for this?

The best art, from painting to fairy tales to commercial fiction must have, in my view, a moral vision. John Gardner put it this way: “I think that the difference right now between good art and bad art is that the good artists are the people who are, in one way or another, creating, out of deep and honest concern, a vision of life . . . that is worth living. And the bad artists, of whom there are many, are whining or moaning or staring, because it’s fashionable, into the dark abyss.” (On Moral Fiction)

And turning again to Chesterton:

All really imaginative literature is only the contrast between the weird curves of Nature and the straightness of the soul. Man may behold what ugliness he likes if he is sure that he will not worship it; but there are some so weak that they will worship a thing only because it is ugly. These must be chained to the beautiful. It is not always wrong even to go, like Dante, to the brink of the lowest promontory and look down at hell. It is when you look up at hell that a serious miscalculation has probably been made. (G. K. Chesterton, Alarms and Discursions, 1911)

There are dragons everywhere. Sometimes they have form, as in, say, a villain wanting to kill good people. Or there might be inner dragons, psychological beasts keeping a character from full form and function in life. Readers read to experience the battle, and the outcome. If the dragon is slain, it’s upbeat. If the dragon wins, it’s a tragedy but also a cautionary tale. In either case, there’s lesson to be drawn (the “return with the elixir” in mythic terms) that helps us make it through this vale of tears.

Erle Stanley Gardner (creator of Perry Mason), once said:

“The public wants stories because it wants to escape.…The writer is bringing moral strength to many millions of people because the successful story inspires the audience. If a story doesn’t inspire an audience in some way, it is no good.”

(The above, BTW, is the governing philosophy of my Patreon site.)

So I offer this up for discussion. Do you think art should have a moral compass? (Yes, we can disagree about what vision is moral; but good art should at least be about making an argument for the vision, don’t you think?)

By the way, I was greatly pleased recently to learn that my oldest grandboy’s favorite bedtime story is “St.George and the Dragon.”