by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Earlier this year I spent three days at Disneyland with the fam, including the two grandboys, ages 4 and 2. Let me tell you, it may be the happiest place on Earth, but for three days it’s also an endurance test. My daughter told me, via her FitBit, that we averaged 21,000 steps each day. My dogs were screaming for mercy.

Earlier this year I spent three days at Disneyland with the fam, including the two grandboys, ages 4 and 2. Let me tell you, it may be the happiest place on Earth, but for three days it’s also an endurance test. My daughter told me, via her FitBit, that we averaged 21,000 steps each day. My dogs were screaming for mercy.

But we had a stupendous time. I mean, how can you not when you experience the park through the wide-eyed wonder of two small boys?

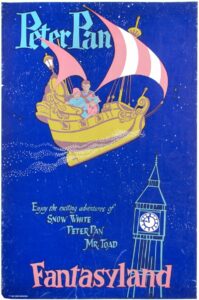

In Fantasyland there are five indoor rides within close proximity of each other. The most popular is Peter Pan. There’s always a long wait to get into this one. Right across the way are two rides for which there is virtually no wait time: Snow White and Pinocchio.

So as I waited in the Peter Pan line, I wondered, Why should this be?

I have some theories. For one thing, Peter Pan seems the most magical because you’re whisked away in a pirate ship to go flying through the sky—over Victorian London and then Never Never Land itself. There’s just something about flying that every kid loves.

Yet why should poor Snow White and Pinocchio be so lonely? There might be one reason parents don’t take their little ones on these rides—they’re scary!

I mean, in Snow White, there’s a sudden turn from happy dwarfs and singing birds to a frightening old crone who turns on you holding out a poisoned apple. From there it gets even darker, with thunder and lightning, and the crone appearing at the top of the hill wanting to smash you and the seven dwarfs with a big rock! (Confession: I recall going on this ride when I was little, with my big brother, and I was terrified.)

Pinocchio has more of a house of horrors type of scare. Pinocchio and Lampwick are taken to Pleasure Island where they smoke cigars, play pool and such. But as a consequence they are turned into donkeys. That’s not all. Just around the corner a giant whale jumps out at you, jaws agape! Sure, you end up safely back in Geppetto’s workshop, but it was one hairy journey to get there.

So I wonder if concerned parents simply don’t want their younger children to be frightened. I also wonder if that might be an opportunity lost. For fairy tales don’t exist in a vacuum. They are meant to be didactic. As G. K. Chesterton observed:

Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. (Tremendous Trifles)

Which invites the question: is great fiction always moral? We know there’s plenty of darkness swirling around, especially since anyone can upload a book or video. But is it “art” to wallow in the darkness?

The respected editor Dave King mused about this at Writer Unboxed:

Why are so many gifted writers drawn to the dark side of life? Why are they driven to present characters who are hard to love or lovable characters in situations that are either hard to follow or hard to endure? Why does it feel like work to read them? And why are they winning awards for this?

The best art, from painting to fairy tales to commercial fiction must have, in my view, a moral vision. John Gardner put it this way: “I think that the difference right now between good art and bad art is that the good artists are the people who are, in one way or another, creating, out of deep and honest concern, a vision of life . . . that is worth living. And the bad artists, of whom there are many, are whining or moaning or staring, because it’s fashionable, into the dark abyss.” (On Moral Fiction)

And turning again to Chesterton:

All really imaginative literature is only the contrast between the weird curves of Nature and the straightness of the soul. Man may behold what ugliness he likes if he is sure that he will not worship it; but there are some so weak that they will worship a thing only because it is ugly. These must be chained to the beautiful. It is not always wrong even to go, like Dante, to the brink of the lowest promontory and look down at hell. It is when you look up at hell that a serious miscalculation has probably been made. (G. K. Chesterton, Alarms and Discursions, 1911)

There are dragons everywhere. Sometimes they have form, as in, say, a villain wanting to kill good people. Or there might be inner dragons, psychological beasts keeping a character from full form and function in life. Readers read to experience the battle, and the outcome. If the dragon is slain, it’s upbeat. If the dragon wins, it’s a tragedy but also a cautionary tale. In either case, there’s lesson to be drawn (the “return with the elixir” in mythic terms) that helps us make it through this vale of tears.

Erle Stanley Gardner (creator of Perry Mason), once said:

“The public wants stories because it wants to escape.…The writer is bringing moral strength to many millions of people because the successful story inspires the audience. If a story doesn’t inspire an audience in some way, it is no good.”

(The above, BTW, is the governing philosophy of my Patreon site.)

So I offer this up for discussion. Do you think art should have a moral compass? (Yes, we can disagree about what vision is moral; but good art should at least be about making an argument for the vision, don’t you think?)

By the way, I was greatly pleased recently to learn that my oldest grandboy’s favorite bedtime story is “St.George and the Dragon.”

Since I still haven’t gained an appreciation of the randomness of abstract art (even though I’ve dabbled in it a time or two), I’d be inclined to say it doesn’t have any compass at all. 😎 I’m sure the artist has a point to it all, but in my experience, it rarely comes through to the art viewer. I’m sure there are those who’d disagree with me.

As to books, as I was reading your post I was trying to think of any book I’d read that DIDN’T have a moral compass (however specifically defined) & I could think of none.

Guess I’d have to read an example to know for sure but reading a book without a moral compass would be reading a random ramble–kind of like the in-print version of abstract art.

randomness of abstract art … I’d be inclined to say it doesn’t have any compass at all.

You are not alone in this, BK. It’s been an argument for at least 60-70 years. The most entertaining take is the brilliant Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word.

I lived in LA growing up. We’d watched Disneyland being built via the Sunday night Disney television shows. We were SO excited to finally go to the park when it was open. I was 9 (math people can now figure out how old I am); my brother was 4. We went on Snow White as one of our first rides. After that, my terrified brother refused to go on ANY more rides, even Dumbo which you can see never leaves the great outdoors. My mom was furious that there were no warnings about scary rides. The next visit, we noticed there was a cardboard cutout of the wicked witch outside Snow White with the alert that if you child was afraid of this, best not to go on the ride.

I don’t like being scared. Don’t ready horror, don’t go to scary movies. My junior high showed movies in the auditorium on rainy days at lunch from time to time. I did what I could to avoid going. Day of the Triffids is one I “don’t remember” seeing, probably because I was either somewhere else, or was hiding in back.

That being said, I read and reread all the Grimms Brothers and Hans Christian Anderson fairy tales at home. My parents had great illustrated versions, and it was reading a “real, grownup book” for me. https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/barnes-noble-leatherbound-classics-the-complete-fairy-tales-and-stories-hans-christian-andersen/1106658826

Terry, I was the same age as your brother when I went on Snow White…and cried out in horror most of the ride. I still remember the stressed-out face of my big brother as he got off and said to my parents, “He screamed all the way through!”

The ride itself is not very long (3 minutes?) but it plunges you into darkness right quick. If I’m not mistaken, the original version had the witch with a “real” boulder at the end, about to come down on you. Now it’s more of a flat silhouette off to the side. Meh.

JSB –

You’ve brought us to the deep end of the pool today, sir.

I’m with you on this though I anticipate individual interpretations (and semantics) may trigger objection for some.

Some artists/authors bridle at the notion of ‘good’ or ‘moral’ art. (e.g. I worked several years with dozens of artists at the Mpls Institute of Arts and many would strongly reject any value or moral influenced ‘judgment‘ of art as restrictive and wrong.)

“Good” art for me is that which has a positive influence on others. Ugliness, strife or evil is all fair game in story/art if its inclusion gives rise to resilience or hope in any consumers reading/experiencing it.

If the objective/result is despair or other negative reader impact (pain, fear, sadness) without any offsetting positive (your ESG quote applies) it fails to meet my individual notion of “good”.

Some argue that anything that triggers an emotional response, be that negative or positive, is good/legitimate “art”. I feel otherwise.

Thought provoking topic, Jim. It flashed me back to discussions decades ago involving pitchers of beer, youth and strong opinions.

Thanks!

Ugliness, strife or evil is all fair game in story/art if its inclusion gives rise to resilience or hope in any consumers reading/experiencing it.

This is, I think, what animates the best of classic Stephen King. In books like Pet Sematary and his miniseries Storm of the Century. The moral is something like, “If you make a deal with the devil, you will pay a terrible price.”

Heck, that may be the oldest story of all time.

All art makes some sort of statement about what is and what should be. What else would drive an artist to create? And I believe one can make an argument for that vision by either describing its triumph or defeat. Orwell’s 1984, for example, offers a clear vision of a humanistic world by depicting its opposite.

All art makes some sort of statement about what is and what should be.

I also think some things that are treated as “art” are mere statements without the “should.” A crucifix in a jar of urine, for example.

This is so timely, as I debate whether or not to see “The Joker.” I mean, it’s not the same choice as Peter Pan vs Pinocchio, but it is the same issue. The media sends out warnings—dark, dark, dark—yet millions of people are going; it’s making a lot of money. Hmm.

When I first started writing this I didn’t have Joker in mind, but you are quite right — it’s the burning topic of the moment vis-á-vis moral vision. I probably won’t go see it, so can’t be definitive about it, but from the previews it looks exceedingly well-made and well-acted. But does that make it great art or dangerous art? Moral or immoral? I suspect there will be articulate arguments on both sides.

I agree with Mr. Gardner: “The writer is bringing moral strength to many millions of people because the successful story inspires the audience. If a story doesn’t inspire an audience in some way, it is no good.”

What would be the point of writing a novel if the story doesn’t have a point? And if it does, shouldn’t it strengthen and uplift readers and help them refine their own understanding of morality by making them think?

Kay, you would think that would be the “point.” Yet there has always been a subversive element that argues virtually any expression in any form is art, and that not having a point is actually the point!

But at some point (ha) you come to a place where if anything is “art” then nothing is art.

Great question…I vote yes.

IMHO, humanity as a whole is born with a need to see the “good” guy win, however each individual defines “good”. When I finish a novel or a movie and can’t figure out who won, who the good guy was, or even the point of the story, I feel like I’ve been robbed of something. I want, at the very least, to know why the story was written.

Sometimes, the bad guy wins. That’s okay. I always tell myself, that’s life. Sometimes that’s how life goes. But, there’s this thing in me that says just because bad wins this time doesn’t mean the story’s over. Maybe there’ll be a sequel.

That’s life, too. The bad stuff in life has a sequel coming, says my faith.

But, there’s this thing in me that says just because bad wins this time doesn’t mean the story’s over. Maybe there’ll be a sequel.

I like the way you put that, Deb. And I think that desire is implanted in all of us. Circumstances and aberrations may squelch it in some, which is a tragedy on many levels.

Great post, Jim. “the deep end of the pool” as Tom said.

This subject of art having a moral compass (or not) is what lead me to begin writing a series for my grandchildren – The Mad River Magic series, middle-grade fantasy, white magic. I would love to see a discussion here at TKZ on how the author implants a moral compass without preaching.

On the subject of your Patreon site, I loved your last short story – “Nabbed.” The twist ending certainly turned the moral compass in the right direction – one ball, ten pins, a strike.

Thanks for tackling this important subject. I look forward to reading everyone’s responses.

Steve, good on you for leaving that legacy for your grandkids. I look forward to sharing my collection of Classics Illustrated with mine.

And thanks for the good word on “Nabbed.” Much appreciated.

My nephew is heading my way for an afternoon of homemade chicken pie and catch up, yeah!, so very brief. Good and great popular genre is deeply moral. It’s the bone structure for those of us write mystery, romance, etc. Anyway, here’s a piece I wrote some time back for my writing blog.

One of the primary hallmarks of genre fiction is its moral core. The characters and their choices may be morally gray rather than the white and black of good and evil, but the reader expects that good will eventually triumph. The good guys will gain some victory, and the darkness will be banished.

If the author fails to deliver on this promise of light over darkness, she fails a fundamental promise to the reader.

In the same way, the major character or characters must have a moral core that helps them recognize the right choices and gives them the strength to follow through, whatever the cost, to reach that triumph over darkness.

Happiness can never be gained without a struggle against the forces of darkness. The darkness may be a black-hearted villain, but its most important manifestation is within the main character who must fight her inner darkness with that moral core.

Sometimes, if the main character is an antihero or shallow chick-lit heroine, the struggle will involve a great deal of protests, whining, and foot-dragging to reach that point, but that point is reached.

Betsy, the Queen of the Vampires, in the MaryJanice Davidson series, is a perfect example of this kind of character. Shallow, shoe-absorbed, and selfish, she whines her way through each book, but her inner moral core always leads her to do the right thing in the end.

If Betsy never did the right thing, this series wouldn’t be the success it is because shallowness won’t hold a reader’s attention or their emotions for very long.

Sometimes, in a series, a character will change from evil to good, or good to evil, but that change must be foreshadowed in earlier choices and decisions. Bart the Bad may be up to no good through the early novels, but the reader should see that he chooses not to ambush the hero because a child is nearby. This not only adds moral complexity to Bart, but also makes his move toward the light more believable.

In the same way, a good guy’s pragmatic or selfish choices will foreshadow the coming darkness.

Marilynn, good thoughts all. I have nothing to add but my thanks for stopping by.

Yes. I absolutely believe a moral compass is imperative. I’ve been giving this a lot of thought in my own WIP. I knew it was there but I didn’t know until recently (maybe I had a good night’s sleep) what it was. It was staring me in the face all along. My moral, I guess my theme, was do the right thing, even if there’s nothing in it for you. Once I figured that out I was able to have one of my characters tell that to my protagonist in the first chapter. It takes her the rest of the story to figure it out for herself. Thanks again for another great article with plenty to chew on.

There was a writing teacher (who taught Dwight Swain) named William Foster-Harris who spoke of fiction as a “problem in moral arithmetic.” Value A + Value (negative) B = ? Some have called this “the moral premise.” It’s a good way to view theme. Sometimes a writer will have this in mind from the start. Other times, it emerges in the writing itself. Either way, it should be clear at the end.

We all have different ideas of what inspires, but I do know that the books I have saved for 60 years (and loaned to grandchildren), and the books/characters I remember from a lifetime of reading, all inspired me in some way. I don’t read or watch horror, but I made an exception with Hitchcock’s “The Birds.” I was inspired by the courage of Tippi Hedren, I recall. I want to be encouraged to be better in some way when I read or watch a movie. How much talent does it really take to inspire someone to feel or act WORSE?

Right on, Kristi. It doesn’t take much to depict the darkness. It takes an artistic hand to illuminate in a subtle yet convincing way.

The Birds was quite controversial in its day. Some critics said it had no moral, that it was “shock for shock’s sake.” The ending of the film is famously ambiguous. Hitch is one of my favorite directors, but I must say I’ve never cared for this one very much.

This is a really good article, and I’ve shared it around on my social media. Props for the Chesterton quotes!

I love moral quandaries in fiction, because they make you ponder and chew on what the right thing might be in this situation. Like the bestselling book, the Lake House, by Kate Morton. A toddler disappears and a family falls apart. Years and years later, a cop comes across the cold case and is determined to find out what happened to the toddler. A million twists and turns unfold as we watch characters pressed in all kinds of ways making all kinds of morally ambiguous decisions … and some very bad, spur of the moment decisions that have terrible consequences. The book is a bestseller for a reason–because each choice is so interesting to chew on. It’s like one of those “what would you do if” party games.

Thanks, Kessie. I haven’t read that one, but you have me intrigued. Two other novels of the same type came to mind. Both of them superb for the reasons you suggest. Mystic River by Dennis Lehane, and A Simple Plan by Scott Smith.

21,000 steps a day! OMG! I assume the little ones had strollers or shoulders to ride on.

I hope many more fiction writers read those wise and inspiring words by Earle Stanley Gardner. If evil won out at the end of a novel I read, I’d throw it against the wall and write a nasty review.

Always love your Sunday posts, Jim.

Thanks, Jodi. Good to hear from you. We are on the same page!

Isn’t that question a can of worms!

I don’t think we want to be converted to a particular way of thinking with art (that X must be good and Y must be bad, and I’m going to hell if I don’t agree), but I like the idea of taking away something when I look at, read, or listen to art.

But, I also like seeing art imitate life: sometimes, the bad wins, but I don’t think that necessarily negates me believing that “good will win”. If anything, when the bad wins, I’m far more likely to continue my belief that “good” will overcome.

Though, labelling morality as “good vs bad” is too simplistic; what we believe as “good” and “bad” is relative. Things are a lot more complicated than that. I’m sure we’ve all done bad things for good reasons, though I’m not sure how many of us have done good things for bad reasons. Could be more than we thought?

As writers, we write sympathetic antagonists, we’re told to not make them “evil for the lulz”. Give them a motivation, give them a tragic backstory, give them something to fight against, and then give the reader the reason to say “yeah, in that situation, I’d probably do the same thing”, or at the very least “I totally get where he’s coming from”. I think doing that cements our own moral compass, cements that line in the sand we’re not willing to cross.

Hope you had some fun at Disneyland! Haven’t been there since I was a teenager and I’m keen to get back with my nieces and nephews when they’re all old enough to remember it. What a magical place.

Good thoughts, Mollie. I do think that when there are crosscurrents of emotion regarding the antagonist, it creates a deeper reading experience. No two-dimensional villains here, thank you!

Joseph T. Sullivan stated this.”… for all creative people in our world, artists of all kinds: sculptors, authors, song writers, painters, musicians, architects…They can pick up our spirits and carry us away from the humdrum and routine; they can lead us to nobler thoughts… [They] can use their talents for the noble, the inspiring, the uplifting. They have such enormous capability for good, their collective influence is powerful…[They] can show us how to look at the stars, not down at the mud and the puddles.”

In order to appreciate the light, we must first experience the dark. I look for the light, but that is of course just my opinion.