by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Happy Father’s Day! I hope all you dads out there get in some good relaxation time. Unless, of course, you’re with your young grandkids. There is no relaxing then! (But you wouldn’t have it any other way.) And I also hope you get a message you don’t hear much these days: You matter.

On another note, there’s a famous line in the John Ford Western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. When the truth of who shot down Valance is finally revealed to a newspaperman, he refuses to run it. “This is the West, sir,” he says. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

I thought about this line via the following events:

Last Wednesday was Flag Day. It’s one day out of the year for Americans to honor the Stars and Stripes.

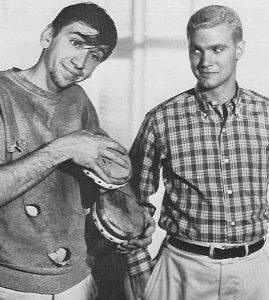

Maynard G. Krebs (Bob Denver) and Dobie Gillis (Dwayne Hickman)

It so happened that on that day I picked a random episode of Dobie Gillis for my wife and me to watch. I was too young to appreciate this TV show in its first run, but I remember my big brother watching it every week. Based on stories by Max Shulman, the show centered on a girl-crazy high school student (Dwayne Hickman) and his beatnik friend, Maynard G. Krebs (Bob Denver, pre-Gilligan). The show actually holds up quite well, via its quick cutting and sharp dialogue (and, if you look fast, appearances by early Tuesday Weld and Warren Beatty).

In this particular episode, it is discovered that Maynard has legit ESP. He can tell what people have in their pockets, what they are thinking, and even predict the future.

His gift is exploited by a local TV station, which brings Maynard on to demonstrate his powers in front of a panel of skeptical experts. Maynard proves his stuff. The station invites him back the next week in order to tell the world who is going to win the upcoming presidential election between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy!

Dobie tries to talk Maynard out of it. But for once in his life, Maynard is being treated with respect. The whole world is going to listen to him.

“Man, that’s like power,” says Maynard.

“Man, that’s like un-American,” says Dobie. “This is a democracy, Maynard! People have the right to vote for whoever they want. If you tell them who wins, people will stay home!”

Maynard is undeterred. On the night of the broadcast, Dobie stands outside the studio sending last, desperate thoughts to Maynard, who ends up doing the right thing. “Like, I don’t know!” he tells the host.

He’s unceremoniously tossed out of the studio. Dobie finds him and says, “Maynard, I’m proud of you! You’re one of the great Americans of all time. Paul Revere, Nathan Hale, Sergeant York, Barbara Frietchie…and my good buddy, Maynard G. Krebs.”

What struck my wife and me was how unapologetically patriotic Dobie was. How many high school students talk like that anymore? Who even knows who Nathan Hale was, let alone Barbara Frietchie?

Interesting that Dobie put that latter name on the list. Barbara Frietchie is the subject of a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier. The poem used to be taught in our schools. Kids would memorize it. I remember my dad reciting it. Based loosely on historical fact, it tells the story of an aged widow looking down from the attic of her house in Frederick, Maryland, as the occupying Confederate army, led by Stonewall Jackson, marches through. She sees them waving their flags, and puts out Old Glory on a flagpole. The soldiers shoot at it, shattering the pole. But Barbara grabs it and starts waving the flag herself. She shouts down at the soldiers the famous line:

“Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, but spare your country’s flag,” she said.

Whittier certainly embellished the facts, but so what? He was creating legend. As with Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” the point was not realism, but idealism. Especially in context. “Barbara Frietchie” was penned during the Civil War; Whittier was a staunch abolitionist looking to inspire the North at a time when Lee and Jackson were beating the pants off it. A comment to an article on the background of the poem says it well:

The essence of “poetry” is not in detailed truths, but in the passions it appeals. Please don’t diminish yourselves by “seeking the truth/s of origin” in any poetry. Simply enjoy the story, the romance and the beauty of human actions.

In our fiction, we have that choice, too. Do we extol “the beauty of human actions” even through the most dire of circumstances? To Kill a Mockingbird comes to mind. So do my favorite thrillers.

And so does Dobie Gillis and all those family shows from the 50s and early 60s, like Leave it To Beaver. The standard criticism about those shows is along the lines of, “No families were really like that!”

Again, that misses the point. The shows were never intended to be cold reflections of reality. They were, first of all, entertainment. But they also carried positive, uplifting moral sentiments. In Beaver, for example, Ward would dispense essential wisdom to his sons. June would teach them to be polite, and how to behave in social gatherings. Wally would protect the Beav from the devilish whispers of Eddie Haskell.

In other words, these shows, as the old song puts it, accentuated the positive. Which is a good thing, in my view. Especially these days.

I’ve always liked this quote by writing teacher and novelist John Gardner, from a Paris Review interview:

I think that the difference right now between good art and bad art is that the good artists are the people who are, in one way or another, creating, out of deep and honest concern, a vision of life…that is worth pursuing. And the bad artists, of whom there are many, are whining or moaning or staring, because it’s fashionable, into the dark abyss….It seems to me that the artist ought to hunt for positive ways of surviving, of living.

What say you?