Death is an uncomfortable subject for many folks. Perhaps it’s the severe emotional reaction people have to death—especially if it’s someone close—that makes the living act in bizarre ways. Or maybe it’s because death’s process is not well understood that causes normally rational individuals to believe in irrational concepts.

Recently, I looked over notes from my coroner understudy days. One training segment was in understanding various cultural practices and traditions about death. This was valuable information, as a difficult part of a coroner’s job is interacting with the deceased’s family, and those relatives can come from a diverse ethnicity with some pretty peculiar beliefs.

For today’s Kill Zone piece, I thought I’d share thirteen strange superstitions about death.

- Coins on the Eyes

The practice dates to the ancient Greeks who believed the dead would travel down to Hades and need to cross the river Styx in order to arrive in the afterlife. To cross over, they needed to pay the boat driver, Charon, so coins were placed over the eyes of the dead so they’d be able to pay the fare.

Secondly, and more practically, many people die with their eyes open. This can be a creepy feeling, having the dead stare at you, and it was thought the dead might be eyeing someone to go with them. Coins were a practical item to weigh down the eyelids until rigor mortis set in—coins being round and fit in the eye sockets as well as being relatively heavy.

The most famous set of eye coins is the two, silver half-dollars set on Abraham Lincoln, now on display in the Chicago Historical Museum.

- Birds and Death

Birds were long held to be messengers to the afterlife because of their ability to soar through the air to the homes of the gods. It’s not surprising that several myths materialized such as hearing an owl hoot your name, ravens and crows circling your house, striking your window, entering your house, or sitting on your sill looking in.

Birds, in general, became harbingers of death but somehow the only birds I personally associate with death are vultures.

- Burying the Dead Facing East

You probably never noticed, but most North American cemeteries are laid out on an east-west grid with the headstones on the west and the feet pointing east. This comes from the belief that the dead should be able to see the new world rising in the east, as with the sun.

It’s also the primary reason that people are buried on their backs and not bundled in the fetal position like before they were born.

- Remove a Corpse Feet First

This was Body Removal 101 that we learned in coroner school. We always removed a body from a house with the feet first. The practice dates from Victorian times when it was thought if the corpse went out head first, it’d be able to “look back” and beckon those standing behind to follow.

It’s still considered a sign of respect, but coroners secretly know it’s way easier to handle a body in rigor mortis by bending it at the knees to get around corners, rather than forcing the large muscles at the waist or wrenching the neck.

- Cover the Mirrors

It’s been held that all mirrors within the vicinity of a dead body must be covered to prevent the soul from being reflected back during its attempt to pass out of the body and on to the afterlife.

This practice is strong in Jewish mourning tradition and may have a practical purpose—to prevent vanity in the mourners so they can’t reflect their own appearance, rather forcing them to focus on remembering and respecting the departed.

- Stop the Clock

Apparently, this was a sign that time was over for the dead and that the clock must not be restarted until the deceased was buried. If it were the head of the household who died, then that clock would never be started again.

It makes me think of the song:

My grandfather’s clock was too large for the shelf

So it stood ninety years on the floor

It was taller by half than the old man himself

Though it weighed not a pennyweight more

It was bought on the morn of the day that he was born

And was always his treasure and pride

But it stopped, short, never to go again

When the old man died

- Flowers on The Grave

Another odd belief is about flowers growing on a grave. If wildflowers appeared naturally, it was a sign the deceased had been good and had gone on to heaven. Conversely, a barren and dusty grave was a sign of evil and Hades. The custom evolved to putting artificial flowers on the grave although it’s now discouraged by most cemeteries due to maintenance issues.

Additionally, it’s always been practice to put flowers on a casket. This seems to have come from another practical reason—the smell from scented flowers helped mask the odor of decomposition.

- Pregnant Women Must Avoid Funerals

Ever hear of this? I didn’t until I researched this article. It seems to have come from a perceived risk where pregnant women might be overcome by emotion during the funeral ceremony and miscarry.

That’s pushing it.

- Celebrities Die in Threes

Most people heard that Ed McMahon, Farrah Fawcett, and Michael Jackson died three days in a row. It’s an urban myth that this always occurs with celebrities and it’s the celebrity curse.

To debunk this, the New York Times went back twenty-five years in their archives and apparently this is the only time three well-known celebrities died in a three-day group.

- Hold Your Breath

Another popular superstition is that you must hold your breath while passing a graveyard to prevent drawing in a restless spirit that’s trying to re-enter the physical world.

That might be a problem if you’re passing Wadi-us-Salaam in Najaf, Iraq. It’s the world’s largest cemetery at 1,485.5 acres and holds over five million bodies.

- And the Thunder Rolls

Nope, not the Garth Brooks song. It’s thought that hearing thunder during a funeral service is a sign of the departed’s soul being accepted into heaven.

Where I grew up, thunder was thought to be associated with lightning and being struck by lightning was always a sign of bad luck.

- Funeral Processions

There’re lots of superstitious beliefs around funeral processions.

First, it’s considered very bad fortune to transport a body in your own vehicle. And approaching a funeral procession without pulling over to the side and stopping is not only bad taste, but also illegal in some jurisdictions. It’s said if a procession stops along the way, another person will soon die, and the corpse must never pass over the same section of road twice. Counting cars in a procession is dangerous because it’s like counting the days till your own death. You must never see your reflection in a hearse window as that marks you as a goner. Bringing a baby to a funeral ensures it will die before it turns one. And a black cat crossing before a procession dooms the entire parade.

One thing I know to be true about a funeral procession is what happens when you leave the back door of the hearse unlatched and the driver accelerates going uphill.

- Leaving a Grave Open Overnight

I don’t know if this is a superstition or not, but I see it as good, practical advice to not leave a grave open overnight. According to the International Cemetery, Cremation, and Funeral Association, the standard grave size is 2 ½ feet wide by 8 feet long by 6 feet deep.

With a hole that big looming in the dark, one could fall in and seriously harm oneself.

Kill Zoners—What other strange superstitions have you heard about death? Have you used any of these in your writing? Feel free to add to this list.

In his early years as a writer, Ray Bradbury made lists of nouns based on childhood memories. Things like: The Lake, The Night, The Crickets, The Ravine.

In his early years as a writer, Ray Bradbury made lists of nouns based on childhood memories. Things like: The Lake, The Night, The Crickets, The Ravine.

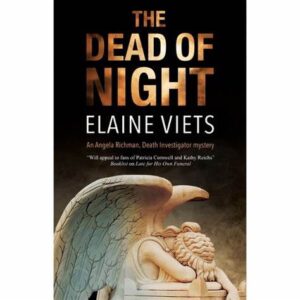

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets

Stay smart and healthy! Enjoy The Dead of Night, my seventh Angela Richman, Death Investigator mystery.

Stay smart and healthy! Enjoy The Dead of Night, my seventh Angela Richman, Death Investigator mystery.  Happy New Year, TKZ family! As much as I love the Holiday Season, with all the parties and the outrageous caloric intake, it’s always nice to return to the normal pace–and to return from our winter hiatus.

Happy New Year, TKZ family! As much as I love the Holiday Season, with all the parties and the outrageous caloric intake, it’s always nice to return to the normal pace–and to return from our winter hiatus.