Today, I’m delighted my pal, multiple-Agatha winner Leslie Budewitz, stopped by to visit. Leslie and I are often found in Montana cafes, noshing pastries while plotting someone’s demise. In this guest post, Leslie discusses how cozy authors can avoid explicit language but still have fun playing with words. Welcome, Leslie!

A recent thread on the Short Mystery Fiction Society discussion list on language—captioned ”Swearing Bad, Murder Good”—prompted me to talk to myself, on my morning walks, about why cozy mystery authors work hard to keep our language clean. You weren’t there that day, so thanks to Debbie Burke for inviting me to share some of my thoughts here.

First, what is a cozy? It’s a subset of the traditional mystery, which itself has quite a range, from the lightest of cozies (Krista Davis, Laura Childs) to historicals (Victoria Thompson, Rhys Bowen) to more psychological drama (Lori Rader-Day, Laura Lippman, Hank Phillippi Ryan). Generally, there is no graphic or gratuitous sex or violence. The killer and victim often know each other, or at least come from the same wider community; these are not stories of serial killers who prey on a certain type of victim or anonymous bombers wreaking havoc on marathon runners and those gathered to cheer them on. Typically, the traditional mystery involves an amateur sleuth, though there are exceptions; Louise Penny’s books are considered traditional mysteries though Gamache and his crew are police officers, aided by locals.

Reading a cozy is a walk on the light side. Think Jessica Fletcher and Murder She Wrote, or Midsomer Murders. The cozy is the comfort food of mystery world, and who doesn’t love a little mac and cheese now and then?

The murder is the trigger, the inciting incident, while the other characters’ response is the story. A bit of an oversimplification, and it’s crucial, in my opinion, to make sure we get to know and care about the victim, and to show how the murder disrupts the community. The estimable Carolyn Hart asks what’s more uncomfortable than murder in a small town where everyone is affected? And she’s absolutely right, though the same is equally true of urban cozies, which focus on a community within a community.

Ultimately, the cozy is about community. The sleuth, usually a woman, is driven to investigate because of her personal stakes. She wants justice, for the individuals and for the community. The professional investigators—law enforcement—restore the external order by making an arrest and prosecuting, but it’s up to the amateur to restore internal order, the social order, within the community. (I could go on about the elements of a cozy. Another time.)

So, what about the language?

Cozies tend toward clean language. SMFS members have pointed out the contradiction in readers who accept murder but dislike cursing or vulgar language. It is a contradiction, a bit. But then again, it isn’t. Murder happens in all social strata—among drug dealers and religious zealots. The murder in a cozy is typically off-stage; we don’t see the blood and gore—a character might, but she isn’t going to describe it for us.

Nor are most cozy settings and scenarios places where you’d expect swearing. Most of us, even if we cut loose now and then, watch our language at a street fair, in a tea shop, at a community theater rehearsal or on a tour boat headed to a clam bake. We might be freer of tongue at home or with close friends, but we know when to watch our language. So do cozy characters.

Who are the characters? Does the language fit them?

A frequent criticism by other writers about deliberately clean language is that it isn’t realistic, that a mobster won’t say “gosh, darn it” or “oh, firetruck.”

Nope, he sure as sugar wouldn’t.

But it goes both ways. Reality isn’t one size. Some people choose not to swear, from personal preference, out of moral or religious conviction, or for other reasons. TV broadcasters train themselves not to swear in private because one accidental “f*ck this sh*t” on the nightly news could cost them their jobs. (Credit for that insight goes to Hank Phillipi Ryan, a TV reporter who writes about them.) Retail shop owners, with some exceptions, watch what they say on the shop floor because most customers don’t want to be surrounded by curse words when shopping, especially if their kids are with them. I gave one of my series protagonists the word “criminy,” borrowed from a former legal secretary who chose it as her dastardly expression when she taught kindergarten; I doubt she knew it’s a contraction of “Christ Almighty,” but the word has long slipped the bonds of its blasphemic origins.

A sleuth who runs a bookstore or bakery and is investigating to right a wrong and restore the social order of the community she loves is not going to suddenly open her mouth and make sailors blush. “I swore under my breath” or “I’d never heard David swear before” makes the point just fine.

Tone matters.

Cozies often involve humor, as the titles make plain. Crime Rib, Assault and Pepper, Chai Another Day are a few of mine. The word play continues as a Spice Shop owner named Pepper says “parsley poop” when she learns a troublesome fact or calls an annoying customer a pain in the anise. The creativity fits and it’s fun.

But what about the killer? They aren’t all little old ladies wielding knitting needles.

No, they aren’t.

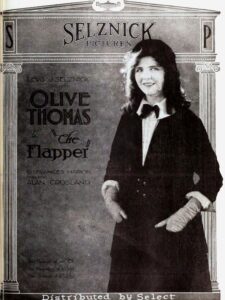

In traditional mysteries, including cozies, the killers are often opportunistic, motivated by emotion and injustice. They may strike out in the spur of the moment. Some act from the conviction that the victim needed killing. Others plot and plan, though pure evil and psychosis are the exception, not the norm. Still, planning a murder doesn’t necessarily equate to a potty mouth. With some exceptions, cozy killers come from the same community as the rest of the characters. They run bars and restaurants, work as TV cameramen, winemakers, and veterinarians, collect movie memorabilia, captain tour boats, and drink good coffee.

Many cozies are written in first person. We see the killer through the protagonist’s lens, although of course, they speak their own truth, sometimes spelled with four letters. When and where killer and sleuth meet might affect the language, too. For example, in one of my books, we first see the killer at a memorial service held in an upscale art gallery, where mourners are wearing linen and silk and sipping sparkling rosé. Not a crowd or a place for vulgarity—though if it did erupt, we might have a sudden silence, followed by a hubbub as the offender is escorted from the scene, all good action for a cozy. Later in the same book, we see the killer prowling around a darkened antique store, aiming to confront and stop my sleuth. The dialogue is limited, as they taunt each other while trying not to give away their locations. Swearing could happen; it doesn’t.

In my latest book, the killer and my first person narrator see each other several times, but only meet face-to-face once, outside a hospital. Again, it’s a place where swearing could happen, but isn’t essential—this isn’t the docks in the dark of night, and their conversation is a battle of wits. The protagonist, a spice shop owner, has no objection to swearing, but rough language isn’t going to help her tease out the killer’s motives or get him to feed her the info she needs to break his alibi. Vulgarity isn’t going to help him convince this pesky woman that he’s the wronged party, that he only did what anyone in his position might have done.

Last, consider the audience.

Cozy readers may be young teens, old ladies, and anyone in between. They are reading to meet the characters, get to know a place, eat good food, and learn about the subject of the book. They are there to see justice done and community restored. Why make them uncomfortable without good reason?

Language affects tone and characterization; it reflects plot and theme; it contributes to setting. If a well-placed “f*ck” or “sh*t” would advance any of those without pulling the reader out of the story, go ahead. Use it. Swearing is just another tool in your writer’s box. But in the well-written cozy, you won’t have to.

~~~

Leslie Budewitz blends her passion for food, great mysteries, and the Northwest in two cozy mystery series, the Spice Shop mysteries, set in Seattle’s Pike Place Market, and the Food Lovers’ Village mysteries, set in NW Montana. The Solace of Bay Leaves, her fifth Spice Shop Mystery, is out now in ebook and audio; paperback coming in October 2020. Leslie is the winner of three Agatha Awards—2013 Best First Novel for Death Al Dente, the first Food Lovers’ Village mystery; 2011 Best Nonfiction, and 2018 Best Short Story, for “All God’s Sparrows,” her first historical fiction. Her work has also won or been nominated for Derringer, Anthony, and Macavity awards. A past president of Sisters in Crime and a current board member of Mystery Writers of America, she lives and cooks in NW Montana.

Find her online at www.LeslieBudewitz.com and on Facebook at www.Facebook.com/LeslieBudewitzAuthor

Pepper Reece never expected to find her life’s passion in running the Seattle Spice Shop. But when evidence links a friend’s shooting to an unsolved murder, her own regrets surface. Can she uncover the truth and protect those she loves, before the deadly danger boils over?

More about The Solace of Bay Leaves, including an excerpt and buy links here: http://www.lesliebudewitz.com/spice-shop-mystery-series/