Ever wonder why pumpkin spice is so popular? The fascinating part is not only does it taste amazing, but many are obsessed with how it makes them feel on an emotional level.

Ever wonder why pumpkin spice is so popular? The fascinating part is not only does it taste amazing, but many are obsessed with how it makes them feel on an emotional level.

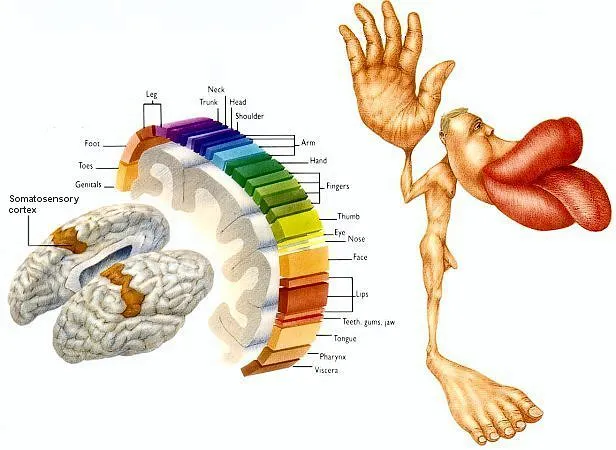

Dr. John McGann, a sensory neuroscientist at Rutgers Department of Psychology, explains how it all reverts back to the olfactory system — our sense of smell — which is complex to say the least.

“Most of what we refer to colloquially as taste is actually smell,” McGann says. “About 70 percent of our [perception] of taste is retronasal smell and then maybe 25 percent of it is true taste: salty, bitter, sweet. But there also additional components: the feeling of creaminess, which really contributes to a perception of flavor [and] your sense of touch. Then there’s an additional sense of pungency, [as in] the burning feeling of pepper from hot wings. That’s your trigeminal system. So, your brain is putting all of these things together.”

The human brain also assembles memories and emotions. In this way, smell is unique from all other senses, which first passes through the thalamus — a relay station of the brain — and goes straight to the olfactory bulb.

“From there it goes to the amygdala, which controls emotion, and to the hippocampal formation, the entorhinal cortex,” McGann explains. “Smell anatomically has a more direct connection to classical memory regions in the brain.”

Do you see where I’m going with this? A scene becomes more impactful and memorable when we include smell.

- If your character is in the forest, include the fresh scent of pine.

- If your character is in the bowling alley, include the stench of bare feet.

- If your character is in a boat, include the salty ocean air.

- If your character is at an Italian restaurant, include the signature tomato sauce.

- If your character is at the gym, include body odor or sweat.

- If your character is in a sauna, include cedar.

- If your character is at a pool, include chlorine.

- If your character is home, include a scented candle, tart warmer, or air freshener.

- If one character is cradling a toddler, include baby shampoo or talcum powder.

McGann recalls a famous scene in Proust’s masterpiece, “Remembrance Of Things Past”, where the narrator eats a madeleine cookie and feels as if he’s transported back in time. The same thing happens to us when we drink or eat something flavored with pumpkin spice.

What makes the flavor so widely relatable is the inclusion of spices like cinnamon, clove, ground ginger, and nutmeg that are more prevalent during the holidays. The aroma of pumpkin is associated with Thanksgiving and autumnal harvest — historically, a prosperous time of year.

Food chemists hit an olfactory jackpot. Hence why pumpkin spice became more than just a fad. It’s a seasonal staple.

“The pumpkin spice blend… It’s about making people happy and connecting them to moments: the changing of the season, of being warm under the covers, but also the memory of spending enjoyable time with family and friends.” Thierry Muret, executive chef chocolatier at Godiva

Think about how the aroma of hot buttery popcorn triggers memories of movie theaters or how lobster tails remind New Englanders of the beach.

Where does your main character live? Does the area have a signature dish? Tickle the reader’s sense of smell to transport them there.

“Pumpkin spice is a novelty smell because you don’t smell it very often and it’s usually a pleasant smell,” explains Dr. Gabriel Keith Harris, director of Undergraduate Programs in the Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences at North Carolina State University. “Combine that with the fact that the part of the brain that processes smell is closely tied to the part of your brain responsible for memories and you have part of the secret to the success of pumpkin spice.”

Makes sense, right?

“Your brain fills in the gaps between the scent of the spices and the memories associated with the smell,” Harris adds. “It takes in everything we’re seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, and tasting, and it combines those sensory inputs with what we already know and believe about our environment.”

This helps to explain why scent is such a powerful driver of emotion.

The irony is that pumpkin spice doesn’t smell like pumpkins. Pumpkins are members of the squash family, and don’t smell like spices. On their own their taste ranges from bland to bitter. What we’re actually smelling and/or tasting is a combination of cinnamon, clove, ground ginger, and nutmeg.

The true genius of the pumpkin spice craze is all about timing. Same holds true for writing. Don’t include a scent merely to check off an item on the to-do list. Include smell for a reason.

Examples:

- To enhance the setting—the MC is hiking up a mountain trail.

- To transport the reader back in time and/or place—flashing back to a memory.

- To pack a more emotional punch—a mother loses her son, but she can still smell him on his favorite football jersey or bed pillow.

- To set the scene—the MC meets a blind date at a restaurant.

“Pumpkin spice plays on what’s known in psychology as reactance theory, which refers to the idea that people will want something more if they are told they cannot have it,” according to Harris. “The seasonality of it is really intentional. If pumpkin spice were available year-round, it wouldn’t trigger such powerful memories and people wouldn’t want it as much.”

Also, when the pumpkin spice craze starts, people don’t want to miss out. They crave being part of a community.

“If you add it all up, the powerful ability of smell to summon up old experiences becomes a mental transportation device, shifting you from summer to fall and it becomes an event people want to be part of.”

Let’s pretend you are the main character. What scents should I expect to smell while reading your life story?

Happy Halloween!

Last week, Sisters in Crime approached me to do a

Last week, Sisters in Crime approached me to do a

Please excuse my absence over the last 7-10 days while I was on deadline. I’m usually a better multitasker. *sigh*

Please excuse my absence over the last 7-10 days while I was on deadline. I’m usually a better multitasker. *sigh*

Fictional truth is never quite as clear as it seems on the surface. Deceptiveness boils down to manipulation, disguise,

Fictional truth is never quite as clear as it seems on the surface. Deceptiveness boils down to manipulation, disguise,  Zoosemiotics is the study of animal communication, and it’s played an important role in the development of ethology, sociobiology, and the study of animal cognition. Writers can also learn from zoosemiotics. Think characterization and scene enhancement.

Zoosemiotics is the study of animal communication, and it’s played an important role in the development of ethology, sociobiology, and the study of animal cognition. Writers can also learn from zoosemiotics. Think characterization and scene enhancement. Keep in mind, a dog could use more than one response at a time. Hence why it’s important to analyze the entire dog, not just one body cue (the same applies to characters).

Keep in mind, a dog could use more than one response at a time. Hence why it’s important to analyze the entire dog, not just one body cue (the same applies to characters).

Bears can kill with one strategically placed swat of the paw, but they have terrible eyesight.

Bears can kill with one strategically placed swat of the paw, but they have terrible eyesight.

Using sharp claws on their fore-flippers, seals punch out 10-15 breathing holes in the ice and maintain the openings all winter but using these holes can mean sudden death if a hungry polar bear is nearby.

Using sharp claws on their fore-flippers, seals punch out 10-15 breathing holes in the ice and maintain the openings all winter but using these holes can mean sudden death if a hungry polar bear is nearby. Skunks use an overpowering odor for defense and can spray six times in succession, but once their foul-smelling liquid runs out it takes up to 10-14 days to refill the glands.

Skunks use an overpowering odor for defense and can spray six times in succession, but once their foul-smelling liquid runs out it takes up to 10-14 days to refill the glands.

Gray whales can submerge for 15 minutes at a time, but a mother’s calf can only hold its breath for 5 minutes, so when under attack by orcas the mother will flip onto her back to create a platform for her baby to lay on, but Momma can’t breathe upside down.

Gray whales can submerge for 15 minutes at a time, but a mother’s calf can only hold its breath for 5 minutes, so when under attack by orcas the mother will flip onto her back to create a platform for her baby to lay on, but Momma can’t breathe upside down.