I was a voracious reader as a kid, and read well beyond my grade level. When other kids were reading the Bobbsey Twins, Nancy Drew, Half-Magic, and Pirates Promise, I picked up To Kill a Mockingbird, Tom Sawyer, and believe it or not, The Dirty Dozen.

Because of my reading habits, I’d already blasted through such novels as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Lord of the Flies, Farenheit 451, and Death of a Salesman well before some of those were assigned in English class. One I couldn’t stand was The Great Gatsby, and still didn’t like it upon re-reading the novel last year.

Not too long ago I started thinking of those classics I’d read as a kid and decided it was time to revisit those novels. Now that I’m pushing 70, I wanted to see how those novels apply these days after a lifetime of experiences, and it was fascinating.

I started with Steinbeck, and the first novel I ever read by this Nobel Prize winning author was Travels With Charley, and that was somewhere around age fourteen. It sparked an interest in U.S. travel that has continued to this day. Then I went back and read Of Mice and Men and by the time I was in high school, The Grapes of Wrath, all before my senior year.

The Bride and I were in Palm Springs a couple of months ago and I ran across that title in an antique store. See, there’s that travel thing and I coughed up five dollars for the well-thumbed paperback reprint circa 1969. Book deadlines left it in my travel bag until last week.

I just finished it yesterday, and was surprised how well it held up. Those who know me understand my fascination with the Dust Bowl, so much that my novel last year entitled The Texas Job was set in the Great Depression. Maybe it’s because of the stories I heard from my family members who survived on scratch farms during that time.

To me, Grapes of Wrath is haunting and somewhat of a minor horror novel, based on what the Joad family endured on their way out to the promised land that proved to be something entirely different. I’d forgotten Steinbeck’s writing style that I feel might have sparked my own, though I don’t always write in third person. He switches back from third, to social commentary in alternating chapters that is unique to this author.

He wrote of the people I grew up with, and his dialogue and descriptions are as comfortable as an old shoe. He used words like “strowed,” and “pone,” and “flour and lard,” and phrases like, “the men squatted on their hams,” and “we got to make miles,” and “she looked down at her hands tight-locked in her lap.” It felt like I was hearing the old folks talking again.

I’d also forgotten that his book was banned after its release back in 1939, because critics said it promoted organized labor, extramarital sex, and violence. Still, to this day, it continues to be a source of controversy for some of those reasons listed above. Reading it today, this novel about as harsh as watching an episode of Law and Order.

Next in line for me is Of Mice and Men, then on to either On The Road, or Lord of the Flies, all read over fifty years ago.

Which classics do you need to re-read, and which ones impacted you?

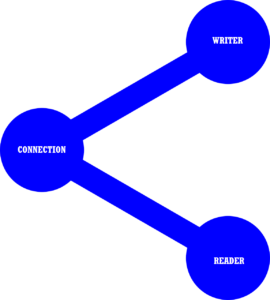

Many writers are not content merely to write a good story. They want to “say something.” This is not a bad impulse. We are awash in a culture of the trivial, the trite, and the downright stupid. It is part of the writer’s calling to stand against all that.

Many writers are not content merely to write a good story. They want to “say something.” This is not a bad impulse. We are awash in a culture of the trivial, the trite, and the downright stupid. It is part of the writer’s calling to stand against all that.

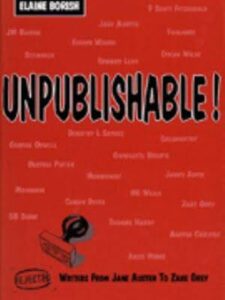

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.” Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”

Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”