We all do it—to some extent, that is. You. Me. The princesses on the top and the paupers at the bottom. It seems to be some primal urge. Some burning instinct to seek self-pleasure, not pain, and avoid the unpleasant or overwhelming.

I’m talking procrastination, of course. The art of putting off till tomorrow that which should be done today. I’d say the majority of writers are procrastinators, and that’s okay. Many times, though, procrastination can be a positive force and not a negative curse. Especially for writers who can perfect their procrastination down to a science.

Procrastination’s best defined as “the act of avoiding doing what you know (or think) you should be doing”. The word descends from the Latin word procrastinare which means “to postpone or delay” and the Greek term akrasia, the “lack of self-control or the state of acting against one’s better judgment”. Leave it to the Greeks and the Romans to label the condition because these ancients were some of the biggest procrastinators of all time. In fact, back then procrastination was viewed as an admirable quality—something that was to be perfected for peak performance.

I know that doesn’t make sense, on the surface. But drilling down, you can make the case that, properly done, intentional procrastination can increase your productivity on important tasks. It’s a matter of setting priorities and focusing on prime output that brings delayed gratification—not a waste time on trivial stuff that seems like fun in the moment (immediate gratification).

Psychologists have done a lot of procrastination studies. Traditional thinking suggests procrastination is nothing more than a time management problem. These thinkers suggest self-discipline is all that’s required to Get Things Done, or GTD as the acronym’s known.

Others aren’t so sure about this. Dr. Tim Pychyl of Carlton University in Toronto and his counterpart, Dr. Fuschia Sirois of Sheffield University in the UK, did a detailed procrastination project and came up with a different suggestion. They saw procrastination, at its root cause, as an emotional management issue, not time.

Drs. Sirois and Pychyl found their studied subjects reacted to procrastination in relation to how they felt in the moment about tackling certain tasks. It’s human nature to avoid pain and seek pleasure, and that emotional connection is just as hard-wired as flight or fight. It’s really about mood when it comes to GTD, say the Docs.

The Docs went on to report the anti-procrastination mindset for GTD is based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) which is a psychological offshoot to Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT). They say that a GTD mentality based on ACT principles allows “psychological flexibility” to tolerate uncomfortable thoughts and feelings (ie: I really don’t want to do this right now, but I know I have to or the consequences will be more untolerable). Recognizing this lets a person stay in the present moment in spite of negative feelings and to prioritize choices and actions that help that person (you) get closer to what you really want in life.

Their studies, the Docs said, found most people couldn’t envision their long-term situation—where they’d be in five or ten years instead of at the moment. Procrastination, or putting off important works, kept their subjects “happy in the moment”. They termed this “mood repair” and found people naturally avoid uncomfortable feelings by putting off tasks-at-hand regardless if the tasks are vital to overall life success.

This doctoral work claims people are actually wired to think of themselves as two different people. They say we have our present selves and our future selves but, strangely, we naturally prioritize our present mood at the expense of our future well-being even though the choice is irrational in our long-term welfare. The Docs reported brain scan waves of people told to envision themselves ten years out were the same as when told to think of celebrities they didn’t know.

Thinking about it, this does make sense. We procrastinate because our brains are wired to care more about our present comfort than our future wellness. That makes it clear we have two ways of dealing with procrastination:

- We make whatever topic we’re procrastinating on feel less uncomfortable.

- We convince our present selves into caring about our future selves.

Yes. I know. This is easier said than done. However, as a serious writer, you have to focus on the long term. It means feeling less uncomfortable about facing the blank page and putting the fingers on the keys. It means completing the current WIP and starting the next—knowing that in five years, ten years, fifteen years, and longer, you’ll have built a backlist strong enough to support you ad infinite.

You’re probably expecting some examples of how to pull off perfect procrastination for writers. To start with, let me suggest you don’t really procrastinate as much as you think. It’s just a matter of setting the right priorities and addressing/attacking the most urgent issues first.

Before I became a serious writer, I was a long-time government worker with high-stress tasks. I faced life and death issues, literally, for over three decades. Often, there wasn’t time to procrastinate. Each day was a challenge to balance urgent and important issues along with non-urgent yet still important jobs.

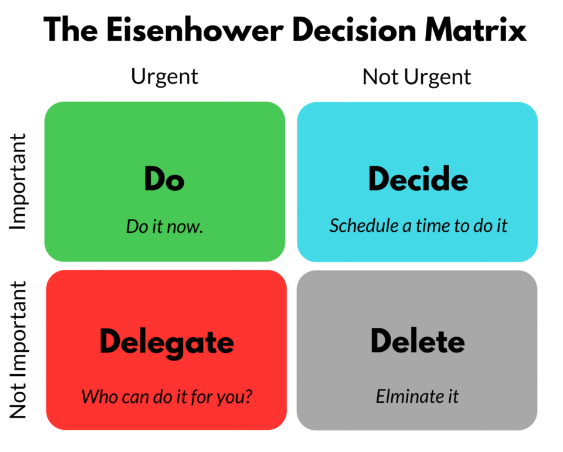

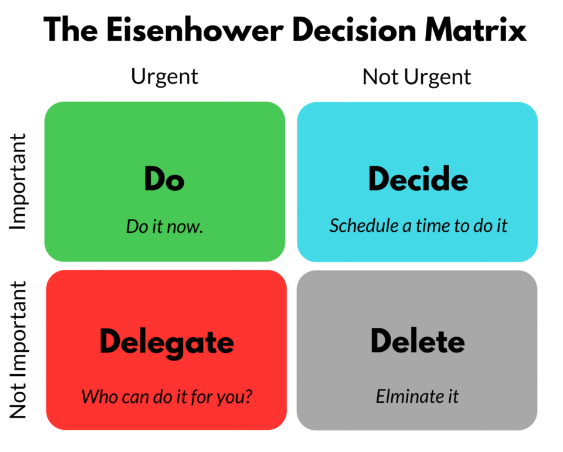

I learned to work within a priority matrix of four quadrants. There’s nothing new or secret about this anti-procrastination process. It’s called the Eisenhower Matrix or the Ike Box and rightly named after the Second World War General and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower who was supremely famous for GTD.

The Eisenhower Matrix deals with two priority dimensions. One is importance. The other is urgency. It’s laid out like this:

Upper Left Box — Important and Urgent Tasks

Upper Right Box — Important but Not Urgent Tasks

Lower Left Box — Not Important yet Urgent Tasks

Lower Right Box — Not Important and Not Urgent Tasks

I’ve used the Ike Box as a police officer and as a coroner. Each profession has a system in place to minimize procrastination and prioritize workload as well as a built-in accountability checker. I won’t get into how they work, but I will let you peek at the Ike Box I have as a writer for this week’s priorities as well as into the near future. It’s all about building the world of five, ten, and more years ahead.

Upper Left — Write blog posts for The Kill Zone and DyingWords, Link backlist in based-on-true-crime series on Amazon, Kobo and Nook, Exercise/Eat/Sleep well, Spend time with Rita, Get a haircut and buy shaving cream

Upper Right — Develop City Of Danger series, Plan July stacked promotion for crime series, Plan podcast with cool co-star Sue Coletta, Publish true crime series on Apple and Google

Lower Left — Respond to two lengthy email assistance requests, Plan print releases for true crime series, Mow the lawn before it’s impossible to walk through and remind our downstairs tenant to pick up after their Rottweiler/Great Dane crossbreed

Lower Right — Renovate writing/recording studio, Have that discussion with Floyd, my neighbor

That’s it. That sums my priorities in this writing and living gig. Nothing fancy or complicated, but it gives me a snapshot of what needs doing right now and what doesn’t matter. I’ve learned (or try to learn) to take only so much on and to say “No” to unproductive time theft. I heard someone say, “When you’ve got it all down to one shopping cart, you’ve got it made.”

Examples of procrastination for writers? Right, I did mention that. One big return in putting stuff off is sitting on your manuscript for some time after you’ve completed a polished draft and before you ship it for publication. This brewing time is precious, and I see that as high-value downtime.

Speaking of downtime, you might view surfing Facebook and watching cat videos as terrible procrastination when you need to GTD. I don’t see it that way, because no one can work all the time and keep peak productivity. Note: If you haven’t read Steven Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Productive People, please do so. This is time well spent.

Time away from the keys and screen lets the creative juices flow. My best downtime is while out for a walk on the waterfront. My worst is after dinner and at the end of the day when I’m creatively done. However, I don’t consider watching an evening’s net stream of the Moody Blues Nights In White Satin (Days of Future Passed) and a TED talk on brain science with Dr. Lara Boyd as a procrastinator’s waste of time which I did last night.

Another prime example of procrastination for writers is leaving a major decision until the last moment and then committing after you’ve had plenty of time to think things over. Rash decisions (gut responses) just to GTD quick can have disastrous consequences as the Lehman Brother organization found out. While researching this piece, I found a Smithsonian Magazine article on a book by Frank Patroy titled Wait: The Art and Science of Delay. Here’s a quote about how the Lehman Brothers destroyed their own future by failing to procrastinate:

“I interviewed a number of former senior executives at Lehman Brothers and discovered a remarkable story. Lehman Brothers had arranged for a decision-making class in the fall of 2005 for its senior executives. It brought four dozen executives to the Palace Hotel on Madison Avenue and brought in leading decision researchers, including Max Bazerman from Harvard and Mahzarin Banaji, a well-known psychologist. For the capstone lecture, they brought in Malcolm Gladwell, who had just published Blink, a book that speaks to the benefits of making instantaneous decisions and that Gladwell sums up as “a book about those first two seconds.” Lehman’s president Joe Gregory embraced this notion of going with your gut and deciding quickly, and he passed copies of Blink out on the trading floor.

The executives took this class and then hurriedly marched back to their headquarters and proceeded to make the worst snap decisions in the history of financial markets. Failing to delay, or procrastinate, their crucial decisions caused Lehman Brothers to go broke in 2008.”

What about you Kill Zone folks? How does procrastination fit into your short and long-term writing plans? Don’t put off commenting until it’s too late.

——

When it comes to procrastinating, Garry Rodgers ranks with the best. Garry managed to put off a writing career until his sixties. Now, he’s making up for lost time with an 8-part, based-on-true-crime series written and indie published within the last two years as well as penning a few stand alones.

When it comes to procrastinating, Garry Rodgers ranks with the best. Garry managed to put off a writing career until his sixties. Now, he’s making up for lost time with an 8-part, based-on-true-crime series written and indie published within the last two years as well as penning a few stand alones.

What Garry Rodgers isn’t putting off is starting a new made-for-net-streaming detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Tagline: A modern city in dystopian crisis enlists two private detectives from its utopian past to deliver street justice and restore social order. Follow Garry on Twitter and checkout his personal blog/website at DyingWords.net.

The 80/20 Principle asserts that a minority of causes, inputs, or efforts usually leads to a majority of results, outputs, or rewards. Taken literally, this means that, for example, 80 percent of what you achieve in your work comes from 20 percent of the time spent. Thus, for all practical purposes, four-fifths of the effort—the dominant part of it—is largely irrelevant. This is contrary to what people normally expect.

The 80/20 Principle asserts that a minority of causes, inputs, or efforts usually leads to a majority of results, outputs, or rewards. Taken literally, this means that, for example, 80 percent of what you achieve in your work comes from 20 percent of the time spent. Thus, for all practical purposes, four-fifths of the effort—the dominant part of it—is largely irrelevant. This is contrary to what people normally expect.

When it comes to procrastinating, Garry Rodgers ranks with the best. Garry managed to put off a writing career until his sixties. Now, he’s making up for lost time with an 8-part, based-on-true-crime series written and indie published within the last two years as well as penning a few stand alones.

When it comes to procrastinating, Garry Rodgers ranks with the best. Garry managed to put off a writing career until his sixties. Now, he’s making up for lost time with an 8-part, based-on-true-crime series written and indie published within the last two years as well as penning a few stand alones.