By Debbie Burke

Recently I attended a Zoom workshop by bestselling historical mystery author Karen Odden. The opening slide of her PowerPoint presentation wowed us. It was a striking photo of an old-fashioned steam locomotive that had rammed through a wall on an upper floor of a building and was hanging down to the street below.

Karen Odden, historical mystery author

For the next 90 minutes, Karen kept us riveted with tales of actual catastrophes from Victorian England. Those events launched her down the research rabbit hole for her historical mystery series. Every discovery led to new story possibilities.

In addition to sharing her research adventures, Karen incorporated an advanced character-building workshop with fresh ideas I hadn’t run across before.

She kindly agreed to visit TKZ for an interview.

Welcome, Karen!

Debbie Burke: The inspiration process for your historical mystery series is a compelling study in itself. Would you walk us through that, including the turning points in the development? What was the moment of realization when you knew you had a winning concept?

Karen Odden: My fascination with the Victorian era began in grad school at NYU, in the 1990s, with a class called “The Dead Mother and Victorian Novels.” The professor noticed all these orphans running around Victorian novels – Jane Eyre, Pip, Oliver, Daniel Deronda, etc. She suggested the orphan was a trope for a profound historical change in England. Whereas in the 18th century, someone’s fortune and social status was inherited from their parents, in the 19th century, people (largely men) could make their own fortunes, in manufacturing, shipping, or whatever. So the orphan was a marker for how it was newly possible to define one’s self without reference to parents.

I found this way of thinking about literature and history fascinating, and I took more classes on Victorian literature, reading everything from Browning’s poems to Henry Morton Stanley’s African memoirs to Darwin’s scientific papers. I wrote my dissertation on the medical, legal, and popular literature written about Victorian railway disasters and the injuries they caused – with an eye to showing how those texts provided a framework for later theories, including shell shock and PTSD.

After graduating, I taught at UW-Milwaukee and did some free-lance editing. But around 2006, I decided I wanted to try writing a novel. For my topic, I leaned into my dissertation, putting a young woman and her laudanum-addicted mother on a railway train and sending it off the rails in 1874 London.

After many false starts, it was published, and I have remained in 1870s London for all my subsequent books. It’s a world I know, down to the shape of the ship rigging and the smells of tallow and lye, and although I have been told (more than once) that WWII books are an easier sell, I hope my books show the Victorian world in all its messy complexity, with all the possibilities for redemption.

DB: What is TDEC?

KO: TDEC is The Day Everything Changes. Basically, it’s the time when the main character’s equilibrium is thrown off, and (with few exceptions) it occurs in chapter one. For example, it’s the moment when Magwitch grabs Pip on the marsh, or Scarlett attends the ball that will devastate her as she finds out Ashley is engaged to Melanie. The reason TDEC is important is every character brings their own personal myth – what they have gleaned from their unique past experiences – to page 1, and that personal myth shapes the way they approach, perceive, and make meaning of every important experience that happens from TDEC on.

A funny story – when I was writing the book that became A LADY IN THE SMOKE (2016), TDEC is when Lady Elizabeth and her laudanum-addicted mother are in a railway crash. But I originally had it in chapter 8. (!) The first seven chapters were backstory about why Elizabeth and her mother didn’t get along and historical facts about railways, accidents, Victorian medical men, and so on. My free-lance editor told me I had to cut it. When I winced, she said it was fascinating; however, it needed to be in my head as I was writing, but not on the page, at least not like that. Much of the material in those 7 chapters is feathered in throughout the book, but the train wreck happens in chapter 1, as it should.

DB: One of your themes is PTSD, a psychiatric disorder that can be traced throughout history under different names. Could you talk about how you identified the condition in the past?

KO: One of the starting points for my dissertation was the account of Charles Dickens, who was in the Staplehurst, Kent railway crash in 1865.

Charles Dickens, Getty Images

He climbed out of his overturned carriage, helped his mistress Ellen Ternan and her mother out, and then began ministering to people. The railway company sent an express to bring passengers back to London, and Dickens went home to bed. But the next day he was so shaky he couldn’t sign his name. He developed ringing in his ears, nervous tremors, and terrible nightmares, dying five years to the day afterward.

Some of the medical men at the time called this “railway spine” — the theory being that all the shaking around passengers experienced inside the toppling carriage caused tiny lesions in the spinal matter, which resulted in symptoms across the whole body. Of course, these lesions were a complete fabrication — but under existing medical jurisprudence, people couldn’t obtain financial compensation for injuries that were only “nervous”; they had to be organic — literally, tied to an organ — and the spine counted.

I am persistently curious about what injuries and experiences “count” in our culture — and how they reach the tipping point of being worth discussing, litigating, researching, compensating, and curing. To my mind, the medical profession has failed us at certain times in history; and these failures can be devastating because the disavowal of injury lays on a whole second layer of trauma.

DB: You divide conflict into two categories: intrapersonal and interpersonal. Please explain the difference and how you use them in your fiction.

KO: For me, intrapersonal conflict occurs within a character and is usually the result of a conflict between an MC’s personal myth – the beliefs they have about the world and themselves, derived from past experiences – and their current lived experience. For example, in The Queen’s Gambit, chess prodigy Beth Harmon learned early on, in the orphanage, that mind-numbing drugs are an acceptable way to escape her world; but later, her lived experience shows that she loses chess tournaments when she plays hung over. So she must amend her personal myth, if she wants to achieve her desire of being chess champion. In parenting, sometimes this is called “natural consequences.”

Interpersonal conflict happens when two characters have personal myths that cannot be reconciled. In The Queen’s Gambit, Beth is a distrustful loner who doesn’t like to depend on others; but secondary character Benny Watts finds a sense of self-worth through teaching other people chess and being appreciated for his efforts. At the level of plot, Beth and Benny are in conflict because both want to be chess champions; at the level of character, they are in conflict because Beth’s personal myth includes the belief that gratitude is a sign of weakness, while for Benny other people’s gratitude contributes to his self-worth.

In my Inspector Corravan mysteries, Michael Corravan is a former thief, dock-worker, and bare-knuckles boxer who was orphaned as a youth and earned his place in his adoptive family by saving young Pat Doyle from a vicious beating. So Corravan comes out of Whitechapel scrappy, good with his fists, and with a belief that his value lies, in part, in his ability to rescue others. These are all fine traits for a Yard inspector.

But as his love interest Belinda points out, being a rescuer means Corravan never has to be vulnerable, and being vulnerable would make him a better listener and a better policeman. At first Corravan ridicules the idea, but when he finally allows himself to empathize with a powerless victim, the case breaks open. So there’s a combination of interpersonal and intrapersonal conflict that brings about a change in Corravan. He’s still a rescuer, but he understands the value of abandoning that role on occasion.

DB: Many writers fall into the bottomless well of historical research and can’t climb out to finish their story. How do you decide when you’ve done enough research and are ready to write the book?

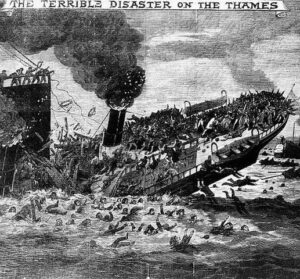

Thames Disaster, Getty Images

KO: Often I begin with a single, large nugget of Victorian history – for example, in UNDER A VEILED MOON, it was the Princess Alice steamship disaster of 1878, in which over 550 people drowned in the Thames. But after a few chapters of writing, I wanted to add complexity to what history says was a mere accident, so I read more and discovered that there was no passenger manifest because it was a pleasure steamer, like our hop-on-hop-off buses. No one had any idea who was on the boat!

I also read some articles about anti-Irish discrimination and thought it would be a good element to have the Irish Republican Brotherhood blamed initially, especially as Corrovan is Irish.

What I’ve noticed about myself is that as I reach somewhere around the half-way mark and know how my story is unfolding, I stop directed reading about the topic, but everything I read and hear incidentally becomes fodder. As I was finishing A TRACE OF DECEIT (about the theft and forgery of priceless paintings), I happened to read a New Yorker article that mentioned a piece of little-known English law that added a new, crazy twist. I try to stay flexible; when I find something intriguing that might fit into my book, I give it a try.

To some extent, setting all my books in 1870s London makes it easy. I have a repository of historical information about economics, laws, social mores, buildings, railways, injuries and illnesses, etc. So I don’t have to reinvent the world with each book. In fact, I’ve recycled several secondary characters, most notably Tom Flynn, the newspaperman for the (fictional) London Falcon.

DB: In How to Write a Mystery, Gayle Lynds wrote, “In the end, we novelists use perhaps a tenth of a percent of the research we’ve done for any one book.” What percentage actually makes it into your books? Do you have suggestions of what to do with leftover material?

KO: I would agree with that! Somewhere around 10-20 per cent. The key thing is to have it firmly in my head as I write — the way I know how to use a toaster, for example — so that historical information feathers in organically. I try to avoid info-dumps (unprocessed history plopped in) and what I call shoe-horning. Sometimes I want to stick in some cool historical factoid, and it just doesn’t fit. So I save it for a fun blogpost!

DB: Is there anything else you’d like to talk about that I haven’t asked?

KO: I’d just like to share that I’ve found it vitally important to develop a robust community of practice. Writing is often solitary; but my books are certainly better because of my beta-readers, and my writing life more joyful and productive (and successful) because of the librarians, booksellers, and other writing professionals I have met. No one told me this about being a writer – that I’d find a smart, generous community, which helps immensely as we all navigate the often challenging publishing industry.

~~~

Thank you, Karen, for sharing your fascinating journey with TKZ!

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at www.karenodden.com.

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at www.karenodden.com.

FB: @karenodden

twitter: @karen_odden

IG: @karen_m_odden

~~~

TKZers: Do you read and/or write historical fiction? What era interests you the most? What’s your favorite research trick?

I was reading in the back yard when Mrs. B came out to let me know that L.A. was in for two days of rain.

I was reading in the back yard when Mrs. B came out to let me know that L.A. was in for two days of rain.

First things first. As I write this, it’s Book Launch Day! Harm’s Way, the 15th entry in my Jonathan Grave thriller series drops today. In this story, Jonathan is summoned by FBI Director Irene Rivers to rescue someone special from the grips of a drug cartel that has taken a group of missionaries hostage in Venezuela. Once the team arrives, however, they discover trouble far more horrifying than a standard hostage rescue. When the first book in the series appeared in 2009, I never would have thought it would have the kind of legs that it has.

First things first. As I write this, it’s Book Launch Day! Harm’s Way, the 15th entry in my Jonathan Grave thriller series drops today. In this story, Jonathan is summoned by FBI Director Irene Rivers to rescue someone special from the grips of a drug cartel that has taken a group of missionaries hostage in Venezuela. Once the team arrives, however, they discover trouble far more horrifying than a standard hostage rescue. When the first book in the series appeared in 2009, I never would have thought it would have the kind of legs that it has.

We often talk about a character’s backstory, including a “wound” that haunts as a “ghost” in the present. It’s a solid device, giving a character interesting and mysterious subtext at the beginning. The wound is revealed later as an explanation. (Think of Rick in Casablanca. “I stick my neck out for nobody” and his casual using of women. The wound of Ilsa’s “betrayal” doesn’t become clear until the midpoint).

We often talk about a character’s backstory, including a “wound” that haunts as a “ghost” in the present. It’s a solid device, giving a character interesting and mysterious subtext at the beginning. The wound is revealed later as an explanation. (Think of Rick in Casablanca. “I stick my neck out for nobody” and his casual using of women. The wound of Ilsa’s “betrayal” doesn’t become clear until the midpoint).