By Elaine Viets

Feeling discouraged, writers? Tired of papering your walls with rejection slips?

When I feel down, I turn to the good book. Not THE good book, but a good book by Elaine Borish called “Unpublishable! Rejected writers from Jane Austen to Zane Grey.”

If you’ve been rebuffed by a publisher, you’re in good company. So was Agatha Christie. Borish says it took Dame Agatha four years to find a publisher for her first novel, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” – and then it sat on a desk for another eighteen months. The publisher suggested some changes to the ending, and Agatha made them. Belgian detective Hercule Poirot finally made his debut in 1920.

Agatha Christie wrote more than ninety titles, and “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” is still in print.

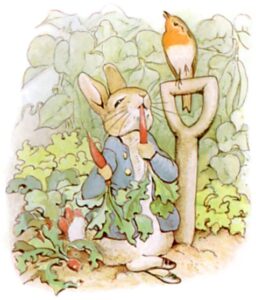

Beatrix Potter, the creator of Peter Rabbit and Flopsy, Mopsy and Cottontail, was a hybrid author. Her “Peter Rabbit” was rejected by six publishers. She used black-and-white sketches, since she was worried that color pictures would make the book too expensive for children. Beatrix finally self-published “Peter Rabbit.” It went through two printings.

In 1901, Beatrix submitted Peter Rabbit again, and the traditional publisher politely rejected it: “As it is too late to produce a book for this season, we think it best to decline your kind offer at any rate for this year.”

The next time Beatrix submitted the book, she had color illustrations. The first edition sold out before the 1902 publication. By 1903, sales were multiplying like, well . . . rabbits. She’d sold 50,000 copies, and lived hoppily ever after.

Dorothy L. Sayers’ books were definitely not for children. “Whose Body?,” the first mystery by the rebellious Oxford scholar, was rejected by several UK publishers for “coarseness” in 1920. Today, the risque parts wouldn’t raise an eyebrow. The novel opened this way:

“Oh, damn!” said Lord Peter Wimsey.

Besides that four-letter word, Dorothy L.’s first book is about the disappearance of a Jewish financier, Sir Reuben Levy. Borish tells us, “When a naked corpse turns up in a bath, Inspector Sugg is eager to identify him as Levy.” Lord Peter says it can’t be “by the evidence of my own eyes.”

And the evidence? The body was (gasp) uncircumcised.

Dorothy L., desperate for money, revised her story, making sure the body could not be mistaken for a rich man. The deceased had “callused hands, blistered feet, decayed teeth” and more. An American publisher bought “Whose Body?” It was published in New York in 1923, and Dorothy was on the way to fame and fortune. Borish writes, rather gleefully, “consider the last words spoken by Lord Peter in the last novel: ‘Oh damn!’”

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

Another publisher, Fredric Warburg, took the book and paid Orwell a hundred pounds. Orwell had the last laugh – Borish says the book sold 25,000 hardcovers in the first five years.

Anthony “A Clockwork Orange” Burgess had a novel about his grammar school experience – “The Worm and the Ring” – rejected because it was “too Catholic and too guilt-ridden.”

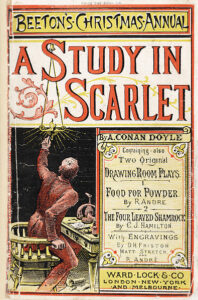

Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”

Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”

These writers endured humiliation, insults, swindles – and in many cases, poverty – and still went on to write books that are read today.

Orwell talked about an embittered Russian who said, “Writing is bosh. There is only one way to make money at writing, and that is to marry the publisher’s daughter.”

Obviously, we writers have to pay attention to rejections sometimes. My agent gave me a good rule of thumb: “If you get the same reason for rejection repeatedly – your plot isn’t twisty enough, or you have too many secondary characters – it’s time to pay attention.”

How many times have you ignored rejections?

I once read that a publisher rejected Animal House because Americans weren’t interested in animal stories.

So funny!

Some of my rejections came with a note that said “I like this but…” then suggestions for revisions. But most of my rejections came because my writing wasn’t “there” yet.

I love the encouragement in your post—if we’ve been rejected we’re in good company. And some writers never experience rejection because they never send their projects out.

Tony Hillerman’s first Navajo police mystery was rejected, with the note, “If you insist on rewriting this, get rid of all that Indian stuff.”

The best advice I ever heard came from novelist David Cates. He turned the rejection game on its head, saying, “Make it your goal to collect 100 rejections.” That worked for me. Every time I received another rejection I didn’t get as discouraged b/c I was closer to my goal.

Funny thing happened. While striving to collect rejections, I started getting acceptances.

When you’re submitting that much, sooner or later someone says yes.

Wonderful reminders, Elaine, that even the great ones were rejected but kept going.

“She’d sold 50,000 copies, and lived hoppily ever after.” 🙂 That Beatrix Potter — they just couldn’t keep her down.

Way back in college I received a personal rejection by editor Ellen Datlow for a short story I’d submitted to OMNI magazine which had an encouraging comment about the immediacy of my writing which buoyed me for a long time after. Eventually, acceptances came, it just took longer than I’d thought it would 🙂

The 27th and final agent rejection for my first novel, NATHAN’S RUN, arrived two months after the book had already been published.

How true, rejections happen to us all. From the first time a boy musters up the courage to risk his self esteem by asking a girl to dance, to the end days when one asks the Almighty for just one more day.

On a long plane ride a fellow traveler and I struck up a conversation to pass the time. The obvious topic of what we did for a living started things off. I told him I was a process development engineer and returned the question to him.

His reply was, “Salesman.” I told him I could never do that job. I don’t handle rejection very well.

He laughed and told me, “We are all salesmen. You have to sell your services and your ideas to others. If you couldn’t get beyond initial rejections, you would never build anything. You have to sell the value of your services to your boss to get a raise or promotion. You are a salesman and the sooner you start acting the part, the better off you will be.”

I took his suggestion to heart and found out how very right he was.

As to the question, “How many times have you ignored rejections?” My answer is, “More than I can count.” I once submitted the required manuscript for a presentation at an annual two day symposium. The gatekeeper savaged my efforts and demanded a raft of changes, all of which I ignored. I delivered the hour long presentation and it was voted the best of the prestigious event.

I realized the gatekeeper’s objective clashed with mine. They wanted conformity with their guidelines and standards. I wanted to wow as many of the attendees as possible.

My worst case rejection lasted over 5 years and involved about 500 people at the manufacturing facility I was sent to fix. The facility was in the deep South and I was a damned Yankee from the northern headquarters. Anyone can do the math, 500 angry people rejecting and/or sabotaging you and your ideas everyday for 5 years is a lot of rejections. For those mathematically challenged, it’s the better part of 1 million rejections. If rejections were an Olympic competition, I might not get a medal, but I’m pretty sure I would get an honorable mention.

“Really now, how bad was it?” you might ask. I took my very young wife and three small children to a Christmas party where the kids would sit on Santa’s lap and get a small gift. We were met at the door by one guy I never had any direct dealings with. In front of my family, he shouted, “What in the hell are you doing here? Don’t you know everyone here hates your guts?”

Not wanting to alarm my wife and children, I just laughed and gently pushed him aside while saying, “Very funny. Everyone here loves me.” And we strode into the party.

I persevered and eventually succeeded in what I was sent to do. Like the rough handed general in Machiavelli’s “The Prince,” with good order restored, it was time for me to move on to the next crisis and let a gentler hand take over.