by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Today’s first page comes to us, it appears, from across the pond. The author identifies it as “Comedic Noir.” Let’s have a look at it, and discuss:

The Bookshop

I step over a shard of a broken concrete paver, its exposed edge a looming obstacle in the fine drizzle.

A raincoat-clad woman is leaning in against the shop front window. Rain water runs in rivulets off her black mac, the gloss and her shape, has me thinking of a wet seal. Her hands cup her eyes and she peers into its shadowed recesses. Red ankle socks cut into her stout doughy legs. It’s mere idle curiosity I’m sure. After all, the advert, secured by a rusty drawing pin to the general dealer notice board, was curling and crisp with age. Nobody’s been interested in these premises for a while.

She startles at a squeal from the sole of my sneaker and jumps back guiltily.

‘Oh my goodness, where’d you pop up from? I didn’t hear you.’ Her voice is grumbly and hoarse, sort of Nina Simone.

‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to alarm you.’ I approach the door and fish the key out of my pocket.

‘Ah, you’re opening up. Great, I’d like a mosey inside. Any idea of the rental? I should’ve asked Daisy.’

‘I’m hoping to sign a lease on it.’ It comes out harsher than I’d intended, sort of snobby and possessive. I do know the monthly rental, but I don’t want to compete with anyone for occupancy. I unlock and push the door. It doesn’t budge. It’s wedged closed with months of accumulated dirt and rotten leaves. I scoop the slimy vegetation away with the toe of my shoe and push again.

‘Here, let me.’ She clutches the handle and puts her shoulder on the frame of the door giving a grunt and a heave. It swings open, taking her with it.

She stands inside, legs and arms akimbo, blocking my access. ‘Spiffy. Plenty of space. Ooh, I like the one raw brick wall, gives character. I can work with that.’

I could shove past her but she’s dripping water like a beached walrus. I clear my throat.

‘Oh sorry.’ She steps aside and makes her way to the right where there’s a wooden counter with pewter coloured cupboards. They contrast well with the red brick of wall.

A pungent mustiness of damp tickles my nose. I hear her opening and banging the doors but I’m drawn to the windows at the rear. They’re splattered with raindrops and the splotches of countless dead midges but when cleaned, they’ll give a great view of the village green. I can picture fellow bibliomaniacs curled in chunky armchairs, soaking up the view and the late afternoon sun.

She’s hollering to me. ‘Any idea about the wiring?’

Who is this woman?

JSB: Let’s mention the POV off the bat. Obviously it’s First Person Present. We recently discussed this, so I’m not going to go over the same ground. As long as the writer has considered the pros and cons, I don’t have a problem with the choice. I’ll only mention that for fans of classic noir it might be a slight speed bump.

Overall, the scene is mildly interesting. But we don’t want mild in an opening page. We want to be grabbed and pulled in. I’d love to see more conflict here—more attitude, more intensity. The narrator is passive. Maybe that’s intended at the start, but at least give him some feeling—annoyance, aggravation, mad because his wife left him—anything. (Note: We don’t know what sex the narrator is, and that’s a problem. I’ll assume for discussion purposes that it’s a man. But do something on this page to clue us in.)

You, dear author, have an obvious felicity with words. But felicity can get you into trouble if you don’t watch it. I’m going to be tough on you because I know you can write. So hang in there!

In Shakespeare’s play King John, Salisbury says:

To gild refined gold, to paint the lily…

Is wasteful and ridiculous excess.

Somehow that’s come down to us as “gild the lily,” probably because it sounds better (I don’t think Bill S. would mind). It means to dress up what is already beautiful, to add a layer that is not only unnecessary, but actually dilutes the intended effect.

This piece has several such instances. The good new is that there’s an easy fix. It’s called the delete key, and the benefits are immediate.

I step over a shard of a broken concrete paver, its exposed edge a looming obstacle in the fine drizzle.

We already know a shard is something broken. We know that if he steps over it, it has to be exposed. We also know that drizzle, by definition, is fine. All those adjectives are gilding the lily. They weigh the sentence down. That’s fatal, especially for noir. Here’s the rework: I step over a shard of concrete paver, its edge a looming obstacle in the drizzle.

Much stronger, but there’s still more work to do. I’m not enamored of looming obstacle. For one thing, it isn’t looming. It’s right there under his foot. Nor is it much of an obstacle if a guy can just step over it.

Here’s a radical idea: ditch the whole thing. This opening line doesn’t add anything to the scene to come. In good noir style, let’s start with the woman!

A raincoat-clad woman is leaning in against the shop front window. Rain water runs in rivulets off her black mac, the gloss and her shape, has me thinking of a wet seal.

We know that shop windows are in front. Cut front.

We know that rain is water. Cut water.

The second sentence is compound, and the second comma is misplaced.

The word leaning is also puzzling. You tell us in the next sentence that she’s peering. But leaning could mean resting her head on the glass because she’s tired, etc.

You can clear up everything this way: A raincoat-clad woman is peering through the shop window. Rain runs in rivulets off her black mac. The gloss and her shape has me thinking of a wet seal. Red ankle socks cut into her doughy legs.

You’ll notice I cut the word stout because that’s the same as doughy. Don’t gild the lily—or the legs!

It’s mere idle curiosity I’m sure.

Cut mere, for that is what idle curiosity is by definition. You also need a comma after curiosity. Or you could write, I’m sure it’s idle curiosity.

After all, the advert, secured by a rusty drawing pin to the general dealer notice board, was curling and crisp with age. Nobody’s been interested in these premises for a while.

A couple of things jolt me here. After all sounds like an expression directed to the reader, rather than the flow of narrative. Also, you lapse into past tense with was curling. And the two sentences seem on the wrong side of each other. I’d suggest: Nobody’s been interested in these premises for a while. The advert, secured by a rusty drawing pin to the general dealer notice board, is curling and crisp with age.

She startles at a squeal from the sole of my sneaker and jumps back guiltily.

Do we really need guiltily? How does he know it’s guilt and not just surprise? Anyway, any adverb here dilutes the strong picture of her jumping back. Let the action itself do the work.

‘Oh my goodness, where’d you pop up from? I didn’t hear you.’

You can gild dialogue, too! After her first statement we don’t need her to say I didn’t hear you. Plus, she just jumped back at his approach. We saw that she didn’t hear him.

Her voice is grumbly and hoarse

Grumbly and hoarse are virtually synonymous. Choose one.

sort of Nina Simone.

Okay, we have to talk about this. Normally, I’m okay with a few pop culture references, so long as they are easy to identify and help set the tone.

But how many current readers, unless they are jazz aficionados, know Nina Simone?

And when I think of her music I picture Nina at a piano singing deep and soulful blues in a smoky café. That is directly opposite the impression I get from a doughy-legged woman crying, “Oh my goodness, where’d you pop up from?”

In short, this is an old and obscure reference, and works against the comic-noir tone you’re trying to create.

‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to alarm you.’ I approach the door and fish the key out of my pocket.

Give the guy some attitude. Create tension. E.g., ‘You mind telling me what you want here?’

‘Ah, you’re opening up. Great, I’d like a mosey inside. Any idea of the rental? I should’ve asked Daisy.’

Ack! He’s going toward the door with a key. We don’t need her to tell him (or us) ‘Ah, you’re opening up.’

‘I’m hoping to sign a lease on it.’ It comes out harsher than I’d intended, sort of snobby and possessive.

Again, too passive. Let’s have some attitude, e.g., ‘I’m going to sign a lease, if that’s what you’re thinking.’ Then you wouldn’t need to gild it by telling us it’s snobby and possessive.

I unlock and push the door. It doesn’t budge. It’s wedged closed with months of accumulated dirt and rotten leaves.

I’m unsure of the physics here. Are “months” of dirt and leaves enough to wedge a door closed? And even so, if they’re on the outside and the narrator is pushing inward, where is the wedge?

‘Here, let me.’ She clutches the handle and puts her shoulder on the frame of the door giving a grunt and a heave. It swings open, taking her with it.

If she’s swept inside, her shoulder wouldn’t be pushing the frame, but the door itself.

‘Oh sorry.’ She steps aside and makes her way to the right where there’s a wooden counter with pewter coloured cupboards. They contrast well with the red brick of wall.

The word well, like the word very, should almost always be cut. Too bland. Also, that little of doesn’t do anything. Just write: They contrast with the red brick wall.

A pungent mustiness of damp tickles my nose.

Mustiness already implies damp, so the of damp is gilding the lily. The sentence is sharper without it.

Man! Seems like a lot of cutting, doesn’t it? But that’s what excellent writing often comes down to—trimming the fat for leaner and meaner prose (especially important in noir.)

Now let me end this on an upbeat note! I like the way the page ends:

I hear her opening and banging the doors but I’m drawn to the windows at the rear. They’re splattered with raindrops and the splotches of countless dead midges but when cleaned, they’ll give a great view of the village green. I can picture fellow bibliomaniacs curled in chunky armchairs, soaking up the view and the late afternoon sun.

She’s hollering to me. ‘Any idea about the wiring?’

Who is this woman?

It’s a nice contrast between the narrator’s vision and the sudden hollering of the woman. Your description here of the splotches and midges and chunky armchairs is solid. You need a comma after midges, but I’d suggest making two sentences out of it: They’re splattered with raindrops and the splotches of countless dead midges. When cleaned, they’ll give a great view of the village green.

As I said up top, writer friend, you have a way with words and promise as a writer. I suggest you write your pages, then come back the next day and look for those gilding-the-lily spots. Pay special attention where you’ve used two adjectives in the same sentence. Almost always cutting one of them makes the writing stronger.

Thanks for your submission. Now let’s hear from the TKZers.

You are offered $10,000 to spend a night alone in a haunted house. Many people swear it’s truly haunted—including a wild-eyed coot whose hair turned white after his one-night stay.

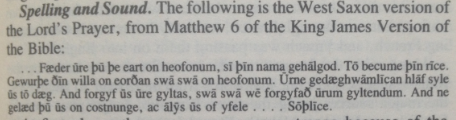

You are offered $10,000 to spend a night alone in a haunted house. Many people swear it’s truly haunted—including a wild-eyed coot whose hair turned white after his one-night stay. It was on an upper shelf and darn near took out my rotator cuff lifting it down. Whoa! This thing is like new! It was hard covered, bound in faux leather with faux gold-gilded page ends, and—I swear to God—had nearly two thousand of them chocked-full of every detail on the English language you can imagine.

It was on an upper shelf and darn near took out my rotator cuff lifting it down. Whoa! This thing is like new! It was hard covered, bound in faux leather with faux gold-gilded page ends, and—I swear to God—had nearly two thousand of them chocked-full of every detail on the English language you can imagine.