I’ve heard writing instructors over the years tout the three elements of storytelling: plot, character and setting. We all know what the words mean, and we know how they apply to creating entertaining fiction, but all too often, I think that new writers think of the elements as craft silos instead of the strands of a craft cable–intertwined elements that must work together if a story is going to resonate with the reader.

I prefer to think of the elements this way: interesting characters doing interesting things in interesting ways in interesting places. (If you’d prefer, you can replace “interesting” with “compelling”.)

Character is king. A plot by itself is merely an outline. It doesn’t come to life until the reader experiences the plot through the eyes and feelings of a character they care about. Setting is merely a descriptive essay until a character interacts with it.

Let’s say, for example, a section of your story is set in a desert on a hot afternoon. An English 101 professor would likely be happy to reward an essay that presents a mental snapshot of the bright sun, colorful rocks and sparse flora. That reporting of facts might please a newspaper editor as well.

But look what happens when we inject characters into the equation:

Bob pushed the door open and climbed out into the brilliant sunshine. Shielding his eyes, he scanned the horizon. The beauty of the place took his breath away. Rock formations glistened in shades of copper, gold and bronze. The vegetation, while sparse, seemed to vibrate with intense reds and blues and yellows. He was stranded in an artist’s paradise.

The description, as presented to the reader, also lets us learn about Bob’s worldview. We don’t have to say that he thinks the place is beautiful, because that’s all in the narrative voice.

Here’s another description of the exact same scene, but filtered through the worldview of a very different character:

Opening the car door was like opening a blast furnace. Superheated air hit Danny with what felt like a physical blow. The desiccated ground cracked under his feet as he stood. As he took in scrub growth and the rocky horizon, he understood that he no longer rested at the top of the food chain. Now he understood why we tested nukes in places like this.

A desert is a desert, right? From a plot perspective, each description takes the story to the exact same place, but by filtering the observations through the characters’ souls, the reader gets to know them better, and they don’t have to endure a disembodied descriptive paragraph.

That voice of the character can infect every paragraph of every scene. I like to say that I make a point as the writer for MY voice to be invisible throughout every story. Every scene is presented to the reader through the voice and view of the scene’s POV character. This is less complicated (note I didn’t say easier) in a first person POV, I think, because the narrator tells the entire story. When writing in third person, one of the critical decisions the writer needs to make for every scene is to determine to whom the scene belongs.

Consider this: Your story requires a scene where a thirteen year old boy steps out the back door of a bar at midnight and lights a cigarette. Let’s say that the kid is signaling someone with the match.

If we present the scene from the kid’s point of view, if he chokes on the smoke, we have a character detail that is different than if he were to inhale deeply and find peace. Is his heart pounding, or is he calm?

If we present the scene from the point of view of the guy being signaled to, his voice will tell us whether he likes the kid or hates him. Is the signal a happy event or a troubling event?

Perhaps we present the scene from the point of view of a passing cop. That would put the story on a different path–unless, perhaps, the cop was the one being signaled.

Assuming that any of the points of view would advance the plot to the same point, we need to decide whose POV is most compelling for the reader. Let’s say now that the scene ends with the kid getting shot. Perhaps we start the scene from the kid’s point of view, and then switch after a space break to the shooter’s POV. Or, vice versa.

These decisions make all the difference between a compelling story and a ho-hum one.

So, TKZ brain trust, what are your thoughts? Do your characters drive every beat of your story?

Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

So here we are on a toboggan hurtling down the snowy mountain called 2022. Seems like a good time to take a look at the current state of book publishing, the better to avoid the rocks, tree stumps, and cliffs scattered all over the slope.

So here we are on a toboggan hurtling down the snowy mountain called 2022. Seems like a good time to take a look at the current state of book publishing, the better to avoid the rocks, tree stumps, and cliffs scattered all over the slope.

Ah, yes, the old plot-driven vs. character-driven debate. I’m not going there with this post, as it’s probably been done to death on The Kill Zone and by far more qualified fiction writers than me. But I will share with you a list of

Ah, yes, the old plot-driven vs. character-driven debate. I’m not going there with this post, as it’s probably been done to death on The Kill Zone and by far more qualified fiction writers than me. But I will share with you a list of  Harry was born into policing royalty. Her great-grandfather was a constable in the Northwest Mounted Police that morphed into the Royal Canadian Mounted Police which Harry’s grandfather joined. Harry’s dad, Hendrik (Hank) Henderson followed suit, and Hank was a high-ranking RCMP commissioned officer when Harry became a recruit.

Harry was born into policing royalty. Her great-grandfather was a constable in the Northwest Mounted Police that morphed into the Royal Canadian Mounted Police which Harry’s grandfather joined. Harry’s dad, Hendrik (Hank) Henderson followed suit, and Hank was a high-ranking RCMP commissioned officer when Harry became a recruit. Harry was left-handed but ate with her right. On dayshift, we always went to lunch at the same diner and Harry always ordered breakfast. Always the same—she hated substitutes. Pork sausages, eggs lightly steamed, shredded hash browns, dry white toast, and black coffee that she loaded with curdles of cream and sacks of sugar. Once served, Harry held her fork in her right, her knife in her left, and chopped everything into one large mangled mess which she mawed down while constantly talking.

Harry was left-handed but ate with her right. On dayshift, we always went to lunch at the same diner and Harry always ordered breakfast. Always the same—she hated substitutes. Pork sausages, eggs lightly steamed, shredded hash browns, dry white toast, and black coffee that she loaded with curdles of cream and sacks of sugar. Once served, Harry held her fork in her right, her knife in her left, and chopped everything into one large mangled mess which she mawed down while constantly talking. She completely and hostilely rejected my concern so, confidentially, I had the boss request a hearing test at her annual physical. After that, Harry reluctantly had hearing aids hidden by her large hair. (We, the other detectives, used to mess with Harry by raising and lowering our voices.)

She completely and hostilely rejected my concern so, confidentially, I had the boss request a hearing test at her annual physical. After that, Harry reluctantly had hearing aids hidden by her large hair. (We, the other detectives, used to mess with Harry by raising and lowering our voices.) Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second investigative stint as a coroner. Now, Garry is a writer with

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second investigative stint as a coroner. Now, Garry is a writer with

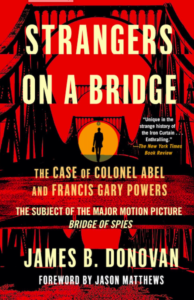

When I begin a new book, I spend some time searching for ideas. Is there some message I want to convey? Or a character who’s anxious to make his/her debut? Is there a particular mystery I want to challenge readers with or a basic theme I’m interested in? I spend time reading good novels and craft-of-writing books. I go for a run and play what-if games. I try not to force the issue, but let my brain relax, hoping for inspiration.

When I begin a new book, I spend some time searching for ideas. Is there some message I want to convey? Or a character who’s anxious to make his/her debut? Is there a particular mystery I want to challenge readers with or a basic theme I’m interested in? I spend time reading good novels and craft-of-writing books. I go for a run and play what-if games. I try not to force the issue, but let my brain relax, hoping for inspiration.