Memory fails, and I think I might have discussed awards sometime back, but I recently had a discussion with another well-known author about contests, and the mega-selling New York Times writer made a couple of good points.

“I like awards because I’m a little selfish. I enjoy seeing my work recognized and the truth is, they look good on my wall and in my office. They go hand in hand with the satisfaction of a job well done, and that’s exhibited by my body of work itself.”

I agree completely.

Neither he nor I came from the Participation Trophy world, and value well-earned recognition. It’s the inspiration that feeds souls.

I was a baby-teacher way back in the late 1970s when that idea of Trophies for Everyone was announced in a staff meeting.

“Each child who participates will get a trophy,” said my moronic starter principal. I worked under several great educators, but this guy phoned it in with two tin cans and a string. Though I have to admit, participation trophies weren’t his idea, but I wouldn’t have put it past him. “It’ll make the kids feel better to take something home for their effort, and will build their self-esteem. There will be no losers.”

Even though it was a faculty meeting, and I was an adult, I raised a hand as I was taught back in elementary school. “No one will try as hard if everyone gets a trophy.”

“The winner’s trophy will be a little bigger.”

“If everyone wins, no one wins. Let em put it this way, once they get out in the real world, they won’t be handing out trophies for a job well done. They’ll distribute paychecks, and there will be no reason to try harder than others, if everyone gets the same amount.”

He blinked once. “You can put your hand down now. Any other questions?”

“Yep. Why did Nixon get us in bed with Communist China?”

“You’ll have to ask the government teacher over there. Now, moving on, some of you are backing into your parking spaces, and that gives our parents the wrong idea that you’re in a hurry to leave school once the day is done…”

All right, I come from a generation who likes to win. I was once cheated out of a first place ribbon in an elementary school three-legged race when the binding came untied after my partner and I crossed the finish line, but I don’t hold that against Coach Mankin (I really do).

One of my grandsons was cheated out of first place in a rodeo mutton busting contest last year. He held on for the full eight seconds, but another competitor took home the buckle because her parents were part of a prominent local family. I knew we’d lost when I saw they were all in their Sunday best and were already lining up for a photo even before the winner was announced.

But back to awards for writing, my friend was right. For authors struggling for recognition in a crowded and confusing landscape, awards offer credibility and a somewhat elevated status for others to see. With 11,000 books releasing every month in this country, these nods toward hard work and creativity help us gain recognition in a firehose output of new books.

I’ll be at the Will Rogers Medallion Award ceremony this time next week, and I’ll find out where my novels The Broken Truth and The Journey South fall as a finalists in Western Modern Fiction, and Western Traditional Fiction categories, respectively.

The awards won’t be accompanied by a check, only by the satisfaction that they were deemed worthy by my peers. That’s what I’m after.

There are two Spur Awards on my wall from the Western Writers of America association. Many of the traditional westerns I read as a kid proudly proclaimed they were Spur winners. As an adult I looked for that recognition on the covers of their books.

I wanted one of my own.

I count six Will Rogers Medallions in my office, and no matter if the above-mentioned novels win Gold, Silver, or Bronze, two more will look good in this collection, in my opinion.

I was also honored with a Benjamin Franklin for my first novel, The Rock Hole, and John Gilstrap and I learned a few years ago that we’d won the Kops-Fetherling International Book Award for our work. I still don’t know what that one is, but the gold award seal is nice.

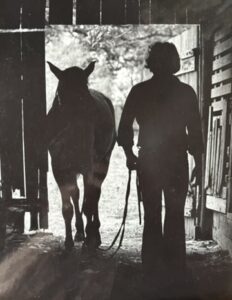

I once took first place in a photographic competition. The photo was a silhouette of my cousin leading his horse into a barn. I had to wake him up late that morning after he’d been out all partying all night, and simply getting him to walk in a straight line was a challenge. The horse cooperated and only required a couple of carrots.

By the way, that barn, the hallway they’re in, and the often patched tack room on the right figured in more than one novel through the years.

Winning that little contest helped spur me on to an extremely successful side career in photography. It lit a fuse that still glows from time to time.

I now have my sights set on a Bram Stoker Award for Comancheria next year. If I win, great. If I don’t, I’ll know that I was in the company of great authors. That’s enough, but I don’t want a participation trophy. Only the real thing, because…

…a respected book award reaches out to both online and store browsers saying, “This is a great book, and worthy of your time and money.” It helps readers weed through the thousands of books that figuratively sag the shelves every year.

It also builds personal self-esteem in an extremely competitive business, and are a way to let other authors know that people out there value your work. Awards come with a word of caution, though.

Some entries require a submission fee. This often comes out of the writers’ pockets, but many times publishers accept that responsibility.

Just because you win first place or gold, doesn’t mean your book will sell any better. There are no guarantees in this business. However, it’ll look good on a resume.

Judges are human. They might see something different in your book, be it good or bad. I’ve judged a number of contests, and when my list was compared to other judges’ opinions, they might not have been the same.

So why bother in the first place?

Personal validation is the best reason I know of. If you see it as that, and no more, you won’t be disappointed.

Jim lived on the cemetery grounds in a quaint yellow cottage with records stored on the lower level. When he began to have medical problems, his son Kevin was hired to assist with the job until a replacement sextant could be found.

Jim lived on the cemetery grounds in a quaint yellow cottage with records stored on the lower level. When he began to have medical problems, his son Kevin was hired to assist with the job until a replacement sextant could be found.

Two weeks ago, I reviewed the 35th Annual Flathead River Writers Conference in Kalispell, Montana. If you missed that, here’s the

Two weeks ago, I reviewed the 35th Annual Flathead River Writers Conference in Kalispell, Montana. If you missed that, here’s the

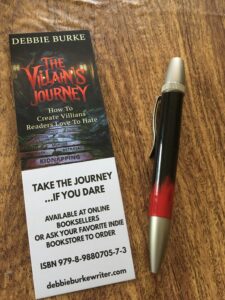

A writing conference is a great chance to build a mailing list. I took the opportunity to encourage sign-ups for my list with a prize drawing—a hand-crafted wood pen inspired by my book,

A writing conference is a great chance to build a mailing list. I took the opportunity to encourage sign-ups for my list with a prize drawing—a hand-crafted wood pen inspired by my book,

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets (2) Elaine: I walked over to him and looked right into his red eyes. We were both the same height.

(2) Elaine: I walked over to him and looked right into his red eyes. We were both the same height. (3) Elaine: The cut on her forehead had been stitched. She’d have a heck of a bruise there tomorrow.

(3) Elaine: The cut on her forehead had been stitched. She’d have a heck of a bruise there tomorrow.

(6) Elaine: I fired up my iPad and opened up the Death Scene Investigation form.

(6) Elaine: I fired up my iPad and opened up the Death Scene Investigation form.