Lighting

Terry Odell

In a couple of hours, the Hubster and I will be heading out on a vacation. I confess I’m a food junkie, and watch a lot of cooking show, so when I saw there was a “Chefs Making Waves” cruise where TV celebrity chefs would be taking over the restaurants, I didn’t need a lot of virtual arm-twisting to sign up. Once we board, I’m going off the grid (the cruise line wants $30 or $40/DAY for ONE device for their internet package) and I’m too cheap for that.

I should be around today to respond to comments, but between having edits for Deadly Ambitions to finish and being in travel mode, I hope you’ll forgive a rerun of a 2020 post I did on dealing with light in your writing.

Light is important when we’re writing—and I’m not talking about having enough light to work by. I’m talking about how much we can describe in our scenes. One of my critique partners questioned a bit I’d written (yes, it’s from one of my romantic suspense books).

She stepped inside and closed the door behind them. Placing her forefinger over her lips, she shook her head before he could speak. She unbuttoned the top button of his shirt. Then walked her fingers to the second, sliding the disc through the slit in the fabric. Then to the third, then the next, until she’d laid the plaid flannel open, revealing the tight-fitting black tee she’d seen at the pond this morning when he’d given her the shirt off his back.

His comment: “It’s night. Do you need to show one of them turning on a light?” Maybe. More on that in a minute.

In a book I read some years back, the author had made a point of a total power failure on a moonless night. There was no source of light, and the pitch-blackness of the scene was a way for the hero and heroine to have to get “closer” since they couldn’t see.

It didn’t take long for them to end up in bed, but somehow, he was able to see the color of her eyes as they made love. I don’t know whether the author had forgotten she’d set up the scene to have no light, or if she didn’t do her own verifying of what you can and can’t see in total darkness. Yes, our eyes will adapt to dim light, but there has to be some source of light for them to send images to the brain. If you’ve ever taken a cave tour, you’ll know there’s no adapting to total darkness.

In the case of the paragraph I’d written, the character had seen the man’s clothes earlier that day, so she’d probably remember the colors, especially since the tee was black. And you’ll note, I didn’t say “red and green plaid shirt.”

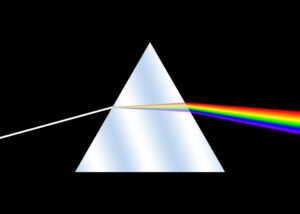

I won’t delve too deeply into biology, but our retinas are lined with rods and cones. Rods function in dim light, but can’t detect color; cones need more light, but they can “see” color. (All the “seeing” is done in the brain, not the eyes.)

We want to describe our scenes, we want our readers to ‘see’ everything, but we have to remember to keep it real. This might mean doing some personal testing—when you wake up before it’s fully light, check to see how much you can actually ‘see’. The ability to see color drops off quickly. So even if you see your hands, or the chair across the room, or the picture on the wall, how much light do you need before you can leave the realm of black and white? What colors do you see first? When it gets dark, what colors drop off first. Divers are probably aware of the way certain colors are no longer detectable as they descend.

Here’s a video showing what happens.

And another quick aside about seeing color. Blue is focused on the front of the retina, red farther back. This makes it very hard for the brain to create an image where both colors are in focus. It’s hard on the eyes. For that reason, it’s probably not wise to have a book cover with red text on a blue background, or vice-versa. You can look up chromostereopsis if you like scientific explanations. For me, I’m fine with “don’t do that because it’s hard to read.”

How do you deal with light and color in your books? Any examples of when it’s done well? How about not well?

New! Find me at Substack with Writings and Wanderings

Deadly Ambitions

Peace in Mapleton doesn’t last. Police Chief Gordon Hepler is already juggling a bitter ex-mayoral candidate who refuses to accept election results and a new council member determined to cut police department’s funding.

Peace in Mapleton doesn’t last. Police Chief Gordon Hepler is already juggling a bitter ex-mayoral candidate who refuses to accept election results and a new council member determined to cut police department’s funding.

Meanwhile, Angie’s long-delayed diner remodel uncovers an old journal, sparking her curiosity about the girl who wrote it. But as she digs for answers, is she uncovering more than she bargained for?

Now, Gordon must untangle political maneuvering, personal grudges, and hidden agendas before danger closes in on the people he loves most.

Deadly Ambitions delivers small-town intrigue, political tension, and page-turning suspense rooted in both history and today’s ambitions.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”