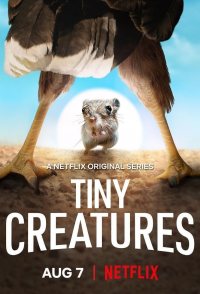

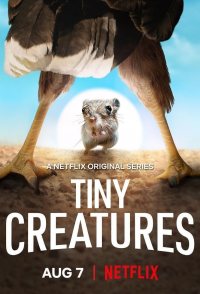

And we’re back with Part II of Tiny Creatures deconstruction. In Part I, we looked at characterization, plotting, pacing, and the importance of raising story questions. In this segment, let’s narrow in on story structure, scene development, character arc, word choices, and story rhythm.

And we’re back with Part II of Tiny Creatures deconstruction. In Part I, we looked at characterization, plotting, pacing, and the importance of raising story questions. In this segment, let’s narrow in on story structure, scene development, character arc, word choices, and story rhythm.

First, a quick review of Tiny Creatures Deconstruction Part I to allow you to see the full character arc. Within a four-part story structure, each Part of the character arc equals 25%.

Part I: The Setup

- introduce the protagonist

- hook the reader

- setup 1st Plot Point through foreshadowing and establishing stakes

- establish empathy for the hero

In the first quartile, Tiny Creatures introduced the viewer to our tiny hero in an empathetic way and we bonded with her right away. We also learned about Raven, who we believed was the villain. And the writer setup the 1st Plot Point — a life or death chase which defined the stakes.

Part II: The Response

- protagonist reacts to new goals/stakes/obstacles revealed by the 1st Plot Point

- hero doesn’t need to act heroic yet

- she retreats, regroups, experiences doomed attempts

- remind the reader/viewer of the antagonistic forces at play

Tiny Creatures excelled in this area as well. Remember when Raven chased our tiny hero around the cabin? That scene established the life or death stakes, and Miss Rat reacted by fleeing. She also feared the human. Which is exactly how she should act in the second quartile of the character arc.

Part III: The Attack

- Midpoint information/awareness causes the protagonist(s) to change course

- hero is now empowered with information on how to proceed

- not merely reacting anymore

- hero also ramps up battle with inner demons

A perfect example of this occurred in Tiny Creatures when our tiny hero summoned the courage to face her fears and freed the raven from the fisherman’s trap.

Now, let’s return to the deconstruction. Keep in mind, we’re still in Part III of the character arc.

Tiny Creatures, Episode 6 Deconstruction Part II

Once released from the trap, Raven cocks his head at the rat. Their gazes lock, linger. “The raven is puzzled by the rat’s action, but grateful nonetheless.” He leaps into the sky.

The fisherman returns from an early morning outing, and the raven calls out to warn Miss Rat to get out of sight (Remember all those intriguing characteristics of the raven we learned in The Setup? Now they take on new meaning. Raven’s intellect actually compliments Miss Rat’s strengths, and together they morph into a winning team). Our tiny hero scurries back into the shack as the fisherman examines his busted trap on the front porch.

As our tiny hero curls into her boot home, the camera pans out to the surrounding area. “The Everglades are home to many animals.” Camera closes in on an alligator. “The American alligator is a keystone species crucial to the health and wellbeing of the ecosystem.” (red herring to get our blood pumping—more tension builds + story questions. Will our heroes face this beast?)

Camera pans out to a body of water in the Everglades, cleverly disguised, and we’re not sure why. (We’ll keep watching to find out. Which expertly demonstrates why it’s important to withhold information.) “But some animals aren’t always welcome. An exotic species introduced by humans, the Burmese python doesn’t naturally belong in the Everglades. Despite this fact, it has everything it requires to multiply and dominate these delicate waterways.” (Notice the harsh “dominate” paired with “delicate.” Perfect word choices send subtle clues of emanate danger.)

The slow and agonizing action of the Burmese python sliding into our tiny hero’s drainpipe would tremble even the steeliest heart. (That image alone proves my point about the Tiny Creatures Netflix series — the writer has mastered the art of suspense. Showing a murder or attack is far less suspenseful than the moments leading up to it. Examples: A lone pinecone crunches under the weight of a stranger’s boot behind you on the hiking trail. The flick of a butane lighter amidst the darkened forest around your property while you sip an evening cocktail at the picnic table. You get the picture. ?)

Sampling the air, the python flicks its tongue. “An intense odor is coming through the pipes.” <dramatic pause> “It can smell a rat.” (Raising the stakes even higher — our heroes don’t stand a chance against this formidable villain.) The python slithers through the drainpipe. “Although the Burmese python is one of the largest snakes in the world, they’re surprisingly agile climbers. To shift their heavy, elongated frame, specialized muscles under their belly propel them forward.” (This smattering of backstory shows how skillful and deadly this predator is AND drives the plot. Lesson: Any and all backstory should be employed with purpose. If it doesn’t benefit the plot, don’t include it.)

<cue dangerous music as the python flows through the dark pipe>

“Continuously flicking its forked tongue, it analyzes its surroundings.” The python emerges from the toilet in the shack (paying off an earlier scene that showed our tiny hero traversing the same route). “The snake can taste (“taste” is another perfect word choice) chemical trails in the air left behind by passing prey.” (Gulp. He referred to our tiny hero as prey! This scene conjures images of the snake swallowing our tiny hero, and our fear mounts with anticipation.)

<cue music that evokes urgency> Camera focuses on the sweet rat munching on a crumb, unaware of the dangerous intruder.

“Instead of adopting an ambush attack, it likes to stalk its unsuspecting prey slowly and silently. Able to open its mouth five times wider than its own head, the rat is an easy meal for the python.” (Can you feel the stakes raising more and more?)

The camera flashes between the snake and our sweet little hero.

“Using heat-sensitive pits lined along its upper lip, the python possesses infrared vision. This allows it to detect warm things.” (setup of 2nd Pinch Point)

The python slithers across the floor as Miss Rat climbs up to a workbench. The close-up of a fly adds to the chilling scene. (We’re glued to that screen as a gazillion questions race through our mind — the epitome of nail-biting suspense.)

Camera gives us a quick peek of outside the shack. “The fisherman has grown up on the Everglades, and he still honors the good ol’ days.” Near the window of the shack, a transparent plastic bag holds water and five coins. “Sunlight passing through the bag acts like a prism, scattering light in all directions. The idea is that it dazzles and confuses flies, keeping them away.” (We think this is just an interesting tidbit of backstory . . . until the camera zooms in on our tiny hero near the bag.) The camera narrows on the python. “But it might not be just the flies that get confused (python’s character flaw).” The snake approaches the bench. “The python has the advantage of not only seeing the rat but also feeling it.” (The writer could’ve used “senses” instead of “feeling,” but the later invokes more terror.)

The python slithers up the wooden leg of an upholstered chair—painfully slow—and we chew our cuticles raw. “Detecting the heat signature as far as three feet away, the rodent appears illuminated.” (Another perfect word choice. “Rodent” ratchets up the tension. Mean ol’ snake doesn’t know our tiny hero like we do!)

Unaware of the danger, Miss Rat munches on another tasty morsel.

“The python slithers ever closer. Its target lies dead ahead.” (2nd Pinch Point, perfectly placed at 62.5%)

Raven lands on the outside windowsill above the bench, but the window is closed. “The raven notices the snake (MRU motivation) and calls out to warn the rat (MRU reaction). But it’s no use. Our tiny hero’s loud munching overpowers the raven’s call (MRU motivation). Time for more drastic action (Scene Goal = Get inside the shack).”

Raven bangs on the glass pane with his strong beak (MRU reaction) to no avail (Scene Conflict = Glass won’t shatter).

“The snake’s hearing is sensitive only to low frequency sounds (villain’s character flaw). And so, it remains unperturbed the raven’s tapping.” With the Burmese python on the cushion of the chair near the workbench, the writer delivers the final blow. “Fixating on its victim, it retracts its body to strike position.” (Tension reaches a boiling point — we cannot look away! + MRU motivation)

Still frantically trying to get inside, Raven slides his beak around the edges of the windowpanes, hammers at the glass, and screeches at high decibels (MRU reaction).

Nothing works. (Suffocating suspense; we’re paralyzed by fear.)

Camera zooms in on the bag suspended next to our tiny hero. “The hanging water bag has gradually heated in the sun (MRU motivation). Now the snake senses two warm targets (MRU reaction + Scene Disaster). Any small movement from either will trigger the snake’s predatory instinct to strike.”

With his bill Raven hammers the crevice between the doors of a shudder-style window (Sequel Reaction).

Helpless, our hero’s furry back faces the python (Sequel Dilemma). Murder is afoot! But right when things look their bleakest (All-is-Lost Moment perfectly placed between 2nd Pinch Point & 2nd Plot Point), the raven busts through the window.

“The raven’s sudden appearance has foiled the python’s ambush.” The snake slithers down the chair leg (MRU motivation). From the safety of the workbench Raven scolds the python as it flees across the floor (MRU reaction + this scene pays off the earlier scene where we learned about the snake’s stomach muscles + Sequel Decision doubles as the next Scene Goal: keep his little buddy safe).

With our tiny hero safe from the python (MRU motivation), Raven hops back on the windowsill (MRU reaction) just as the fisherman enters the shack. The Burmese python in his shack (MRU motivation) causes him to snatch a grabber tool off the wall (MRU reaction).

“Usually the cryptic nature of these snakes makes them hard to detect in the grass. But in the shack, there’s nowhere to hide.”

With the mechanical grabber, the fisherman grips the snake by its head and bundles it up in a long pillowcase. “Expertly catching the snake, the fisherman plans to take it far away.” He loads the python-filled-sack on the boat (MRU motivation). “The rat retreats to the safety and protection of her home (MRU reaction).”

<cue peaceful music as we roam the Everglades> The narrator adds a few lines about the rich landscape (weaving in backstory and allowing the viewer a well-needed break = expert pacing) as the fisherman returns home. “The waters and banks of the Everglades provide humans with endless opportunities.” Inside the shack, the fisherman turns on a gas burner and sets the tea kettle on top. (A close-up of the flame forewarns a potential hazard.)

“After an exhaustingly long day on the water, the fisherman’s work isn’t done yet. He sets about preparing and maintaining his much-loved equipment, working late into the early hours of the morning.” (2nd Plot Point, perfectly placed at 75%)

Our tiny hero curls up in her boot and falls asleep.

The fisherman makes and repairs lures at the workbench. “Such delicate work requires a lot of focus.” He scrubs a hand across his weary eyes. “But, as the saying goes, you shouldn’t burn the candle at both ends.” (forewarns danger + further sets up Climax.)

Our tiny hero peeks out from the boot at the fisherman, who leans back in his chair. Light snoring fills the room (MRU motivation). “A rat never passes on an opportunity to fuel up, and she quickly collects crumbs dropped by the fisherman.” (MRU reaction)

Wicked cute close-up of our tiny hero munching away on a snack (just sayin’). “The noise of the whistling kettle draws the attention of the rat, who anxiously watches as a gust of wind through the opened window ignites a disaster.”

The tail end of a paper towel roll catches fire — <cue dramatic music> — and a flaming sheet falls to the floor. (Climax begins)

Character Arc Part IV: The Resolution

- hero summons courage and growth to come up with a solution

- overcomes inner obstacles

- conquers the antagonistic force

- all new information must be referenced, foreshadowed, or already in play by this point to avoid deus ex machina.

“Unaware of the catastrophe spreading around him, the fisherman slips into a deeper sleep.” Music from his ear buds lulls him into tranquility.

Smaller fires break out everywhere (MRU motivation).

“The rat realizes she must act fast if she is to save her home (Scene Goal).” She scans the room. But she’s so tiny (Scene conflict). She scampers up to a wooden rack of pots and pans suspended from the ceiling, and chews through the rope (using the same behavior she learned at the Midpoint when she freed the raven from the trap; thus, this scene also pays off that earlier scene + MRU reaction). Pots and pans crash on the floor.

“The rat’s actions fall on deaf ears.” (Scene Disaster)

Like a black beacon of hope, Raven emerges through the smoke-fueled haze (Sequel Reaction). He lands on the fisherman’s crossed leg, but he doesn’t wake. <cue dramatic music> He screeches and squawks. The fisherman is out cold (Sequel Dilemma).

“The raven calls loudly. It appears to be trying to help the fisherman (nice role reversal, right? Which also illuminates Raven’s true character—3rd Dimension of Character). The raven is not giving up. This situation calls for more drastic measures.” (Sequel Decision doubles as the next Scene Goal = save his little buddy and the fishing shack)

Fire dances dangerously close to the fisherman’s leg as our two heroes communicate, as if forming a plan. But Miss Rat has done all she can. It’s up to Raven now.

While the rat looks on in horror, Raven’s gaze follows the wire from the ear buds to the human’s chest. Flames grow higher around the fisherman (MRU motivation + Scene Conflict).

<cue louder dramatic music> “Time to get physical.” Grabbing the wire in his beak, he tugs and pulls, but it’s no use. Those ear buds won’t budge (Scene Disaster). Nonetheless, he preserves. With all his might Raven muscles one last jerk (Sequel Reaction) and the ear buds pop loose.

“The fisherman’s woken to an alarming spectacle (Sequel Dilemma).” Raven escapes to the windowsill (Sequel Decision = survival) as the fisherman jolts to his feet. Our tiny hero ducks out of sight. “Fires are common in the Everglades. And luckily, he is well-prepared for such an emergency.” The human extinguishes the blaze.

“The heroic efforts of both the rat and the raven meant the fire didn’t get the chance to cause too much damage. The human has cheated death. And he has the rat and the raven to thank.” (Nice twist, right?)

The camera narrows in on both these amazing animals. Raven takes to the sky as our sweet rat climbs down to the floor (Scene Goal = to rest after a job well done).

“But the rat is left without a home.” Camera zooms in on her charred boot (Scene Conflict + setup of the ending). “She must find a new place to rest her weary head.” Our tiny hero climbs into a duffle bag, and her tail slips beneath the partially opened zipper.

Come morning, the sun rises to a new day.

“Troubled by the fire, the fisherman seeks solace on the water.” He collects his equipment, including the duffle bag (Scene Disaster), and sets off on his boat to clear his mind.

Our tiny hero’s nose twitches out a small opening in the bag. As the raven’s gaze follows his buddy being swept away by the human, his lower bill slacks. “Concerned by where the fisherman is taking the rat, the raven follows closely behind from the air.” (Sequel Reaction)

Camera pans out to show the vastness of the Everglades (indicates danger + story questions. Where will our tiny hero end up?). The boat putts through an open channel.

“The fisherman has an unexpected stowaway. But luckily for the rat, she comes from a long line of seafaring ancestors.” (This fact comforts the viewer and begins the setup of the denouement.)

Camera narrows on our tiny hero’s innocent face, shadowed by the duffle bag (Sequel Dilemma).

“As the boat engine stops, he sets up his fishing equipment.” The fisherman unzips the duffle bag but doesn’t spot the rat. “The rat owes a lot to the fisherman. The shack has provided a shelter to her and any future offspring.” (Perhaps the human isn’t all bad after all.)

Our tiny hero crawls out of the bag and into unfamiliar surroundings. Still, she remains quite perky (3rd dimension of character — her true character. And we love her even more.)

He casts. Casts again and again.

“All over the Everglades animals do what they must to survive.”

Camera flashes to the alligator, the python, the iguana, the fly, and then a wide pan from above showing the raven soaring toward the boat with his majestic outstretched wings. (Fantastic cinematography! Which novelists can also create by etching a vivid mental picture in the reader’s mind.)

“In a delicate ecosystem such as this, a balance between predator and prey is critical.”

Raven lands on the boat (Sequel Decision = ensure his little buddy’s safety).

“Through their trials and tribulations, the rat and the raven have developed a mutual respect and understanding for one another. These two lonely souls have formed an unlikely bond, proving that no matter where you’re from or who you are, it’s your actions that truly define you.” Silhouettes of our two heroes perched on the side of the boat.

“The once great rivalry that existed between them has transformed into an even greater friendship.”

Raven and Miss Rat turn to face each other as the sun sets in the background, brilliant orange and blue hues splashed across the horizon.

“Now with the support of one another, anything is possible.” (What a great last line! We leave the story with our hearts overflowing with love for these two incredible animals.) And the denouement is complete.

Highlights of the Writer’s Skill

The writer locked us in a stranglehold from the very beginning by raising the Central Dramatic Story Question (shown in Part I). Which became the jumping off point for more and more story questions. Each scene written with a purpose, to either setup a future scene or pay off an earlier one. The proper stringing of scenes ensures the viewer’s attention would never waver.

Also notice how the writer never loosened the death-grip around our throats for more than a brief moment (perfectly placed respites). And through characterization (shown in Part I), the writer periodically forced the viewer to change our perception of the hero, anti-hero, and almost every villain we encountered. Most importantly, perfect plotting kept us engaged from the first sentence to the last.

What’s not to love about Tiny Creatures?

You’ve just committed the perfect murder (all that research finally pays off!), but to be successful the cops can’t find the corpse. Your DNA, a stray hair, fibers, or fingerprints might lead them back to you.

You’ve just committed the perfect murder (all that research finally pays off!), but to be successful the cops can’t find the corpse. Your DNA, a stray hair, fibers, or fingerprints might lead them back to you.

What’s one activity you’ve always wanted to try but haven’t?

What’s one activity you’ve always wanted to try but haven’t?

If you could relive your writing life from day one, would you change anything?

If you could relive your writing life from day one, would you change anything? Success comes in many forms. No two writers view success in the same way. Sure, if we’ve had a film adaptation of our novel, then I think we can all agree that’s a success story.

Success comes in many forms. No two writers view success in the same way. Sure, if we’ve had a film adaptation of our novel, then I think we can all agree that’s a success story. Picture this. You’re

Picture this. You’re