A Different Conference Experience

Terry Odell

If all has gone well, when you’re reading this, I should have had my first cataract surgery yesterday, so forgive me if I don’t respond to comments. Surgery went very well, so I’m back at the computer.

I attended the Flathead River Writers Conference, where I had the pleasure of meeting fellow TKZ blogger, Debbie Burke. In her post yesterday, she said I’d have pictures to share, so here are a few to start.

I’ll stick in a few more throughout the post.

This was a very different kind of conference for me. My decision to attend was to get away for a few days, meet some new people, and, most importantly, recharge the batteries. I’ve always attended genre-based conferences, and most have been much larger. This one (under 100 attendees) didn’t hit my overload button. Also, to fulfill the battery recharging goal, I arrived two days prior to the opening session. Debbie was generous enough to play tour guide, so I got to see a lot of the area. Including, I must add, places Debbie used in her books. An added perk: she knows where the best rest stops are.

A few highlights for me from the sessions. (Let me point out, this was not a ‘business networking venture’ for me.) John Gilstrap swears that all of the business takes place at the bar. He’d have been disappointed here, because the conference hotel didn’t have a bar. Or a restaurant.

One of the “speakers” Dr. Erika Putnam, a chiropractor/yoga instructor, had everyone participating in stretches and poses designed to counteract the “all day in front of a keyboard” neck, shoulder, and back stiffness. Another was the Montana Poet Laureate, Chris La Tray, a member of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, who gave poignant yet very entertaining talks.

Another highlight was when the two agents in attendance, Zach Honey and Julie Stevenson did cold reads of the first page of anonymously submitted manuscripts. (Sound familiar?) The submissions were read aloud by conference staff, although the agents had hard copies so they could read along.

Honey focuses on representing thrillers, and Stevenson wants literary fiction. Most of the submissions leaned toward the literary end of the spectrum, and I was left cold. I could hear JSB saying “Nothing’s Happening!” Pretty Prose doesn’t do it for me. Their comments were kept short and superficial, but there were one or two submissions they thought they’d want to see more of. I’m sure those authors were thrilled.

Author Mark Sullivan’s talk on day one about his path to success was interesting, but it was his talk on day two that gave me my biggest takeaway. He spoke of the connection between the body and the mind. He suggested that if you’re having trouble finding the emotional center of your character, picture what that character’s body position would be, then get into it yourself. Something to try, for sure.

He did something else I’ve never seen at any other conferences, which was to lead the group in a meditation session. Sue Coletta talked about breathing, and we did similar exercises. He also addressed something that resonated with me. “Too much to do” anxiety. Sullivan pointed out there’s no point in getting upset about something that happened in the past. It’s over and done. Likewise, you can’t fret about what’s in the future. You can only live in the “now.” Do one thing at a time, and wipe out the rest. Looking at a ‘to do’ list of 20 items is daunting. Don’t think about the 20, deal with the one.

This suggestion came in handy when I arrived home and considered everything I had to do. There were the household tasks, the ‘catch up’ tasks, and the ‘get everything done before my cataract surgery’ tasks. Instead of freaking out, I was able to focus on one thing at a time, and the usual knotted stomach wasn’t an issue.

He left us with these words: The universe is in a state of expansion. If you’re in a state of retraction, you’re fighting the universe. Don’t get involved with yourself.

What about you, TKZers? Do you ever need to get away and do something a little different? Was it worth it?

Available Now

Available Now

Deadly Relations.

Nothing Ever Happens in Mapleton … Until it Does

Gordon Hepler, Mapleton, Colorado’s Police Chief, is called away from a quiet Sunday with his wife to an emergency situation at the home he’s planning to sell. A man has chained himself to the front porch, threatening to set off an explosive.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

.

.

C.S. Lakin is an award-winning author of more than 30 books, fiction and nonfiction (which includes more than 10 books in her

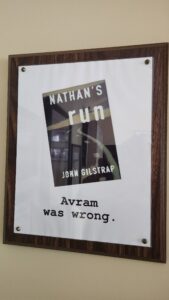

C.S. Lakin is an award-winning author of more than 30 books, fiction and nonfiction (which includes more than 10 books in her  I wish I could say that I shrugged off his cruel dismissal–well, I did eventually, I suppose–but it took more years than I care to admit. Upon publication of Nathan’s Run, one of my classmates from that workshop gave me a heartwarming plaque that hangs in my office in clear view as I write this.

I wish I could say that I shrugged off his cruel dismissal–well, I did eventually, I suppose–but it took more years than I care to admit. Upon publication of Nathan’s Run, one of my classmates from that workshop gave me a heartwarming plaque that hangs in my office in clear view as I write this. For the last few years in L.A. we’ve been invaded by a nettlesome pest called the No-See-Um. That’s because, as the name implies, they’re hard to see. Of the family ceratopogonidae, they are tiny flying demons who bite and suck your blood.

For the last few years in L.A. we’ve been invaded by a nettlesome pest called the No-See-Um. That’s because, as the name implies, they’re hard to see. Of the family ceratopogonidae, they are tiny flying demons who bite and suck your blood.