It’s been nearly 45 years since Avram Davidson, writer-in-residence at the College of William and Mary told me at the end of two semesters of toxic mentorship that I had no talent and that I should not bother to pursue my dream of becoming a writer. He was old and cranky then and he didn’t have the decency to stick around on the planet long enough for me to gloat at him.

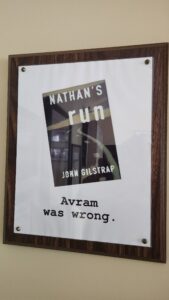

I wish I could say that I shrugged off his cruel dismissal–well, I did eventually, I suppose–but it took more years than I care to admit. Upon publication of Nathan’s Run, one of my classmates from that workshop gave me a heartwarming plaque that hangs in my office in clear view as I write this.

I wish I could say that I shrugged off his cruel dismissal–well, I did eventually, I suppose–but it took more years than I care to admit. Upon publication of Nathan’s Run, one of my classmates from that workshop gave me a heartwarming plaque that hangs in my office in clear view as I write this.

I’ve written about this experience before, but it was brought back the front of my mind by a fictional confrontation that occurs in the excellent Netflix series, “Sex Education.” (Lest there be any doubt, this is not one to watch with the kiddos.) The scene in question occurs in the show’s fourth season, when our heroine, Maeve, has come to America from England to attend a college workshop conducted by the famous and fawned over literary genius, Thomas Molloy, who spills out quotable nonsense about how writing should take something from the writer. This is an exercise in suffering for one’s art.

While the other students in this workshop are bowled over by this pretentious twit, Maeve is more circumspect, sharing with him that she preferred his first book over the second one that won all the prizes. He’s impressed, he says, and then he tears her work apart under the guise of helping her tap that deep vein that makes writing hurt. When she finally pens her new first chapter, he tells her–wait for it–that she does not have the talent to make it as a writer.

Yeah, I had a flashback. I haven’t finished the season yet, but I can only hope that Maeve will be able to rub the asshat’s face in it before the final credits roll.

There’s an X Factor to teaching that I don’t pretend to understand. The best teachers in my life found a way to be thoroughly honest in their assessment of my work, driving me to be better without breaking my spirit. The problem with assessing art is that creativity is by its very nature relative. There is no objective standard, yet we all know bad when we see it. And then, in the truly confusing circumstances, we see stories and art that we know is objectively bad yet it still moves us. Those pieces are victories for the creator.

The lectern is a powerful thing. To stand there behind the mic is to be perceived as an expert by the people in the audience who are looking back at you. This is an opportunity to inspire. Or foment anger. Provide hope or project pessimism. If you’ve been to a writer’s conference, you’ve no doubt encountered the speaker who has experienced only failure, and whose mission seems to be to make the dream of publication seem hopeless.

Even if it were true, what’s the point of making people feel sad? Everybody knows that writing is hard and that getting published is even harder, yet people succeed at it every day. Why not concentrate on the probability of success–however much smaller than the probability of not-success–and fire people up to keep going?

I think there’s a special place in hell for people who try to ruin other people’s dreams.

What about you, TKZ family? Did you have teachers or coaches or bosses who inspired you to do things you never thought possible?

For some reason, what you have described seems to run though the business of teaching writing.

Not all teachers by any means but it’s there, like the mud vein in a shrimp.

I taught for fifteen years online for three colleges and the greatest student motivator I ever saw was someone in that student’s background telling them “You just aren’t good enough.” So maybe Davidson did you a favor.

Three professors come to mind, Prof. Philip Norvell who taught oil and gas law and Prof. Jake Looney who taught water law at the University of Arkansas-Fayetteville and Prof. Lonnie Beard who was my Masters in Law chair.

In particular Prof. Norvell looked like he would have been more at home on the deck of an oil rig than in an office at the U.

All three were practical people with a gift for connecting with students.

About 1973, I signed up for a “writing to sell” course at Torrance Adult Ed. The teacher, Edith Battles, became my friend and mentor until she passed on in 2008. I ran many manuscripts past her for much of that time. I still have some of her old books on writing, dating back to 1916. Her knowledge of writing was vast and her critiques were always gentle and incisive.

My beloved high school English teacher, Mrs. Marjorie Bruce, thought she saw talent in me and encouraged me to keep writing.

The opposite happened in college, where I was told my stuff didn’t have “it,” and that you couldn’t learn “it,” especially from books on writing. While they were not mean about it, they were certainly sure of themselves. That’s bad enough. To be soul crushing to boot is, as you put it, Dante territory.

I kept in touch with Mrs. Bruce until her death at age 90. She lived to see me become a published author.

I had an instructor in college who inspired me. I was an older student and this was my first class in creative writing. The first day, he introduced himself, as Mr. Staley. He announced that if anyone thought it would be an easy class they should leave. He also said that he only had seen one A paper and he wrote it. I thought what a jerk! I saw it as a dare. We had a major paper for the class. I worked hard on it. It was a short story. We had meetings with him 3 times in the term for him to check on our work. He would give encouragement and critique. I got an A- on it. I asked him why the minus, and he said everyone has room for improvement. He also wrote the most encouraging letter of recommendation for a scholarship for the next year. In the end, I considered him the best teacher that I ever had.

This is a tough one for me. When I was in high school, women were still second-class citizens. Our career paths were pretty much limited to being a secretary (that’s what they were called), a nurse, or a teacher. None appealed to me.

Women went to college to have a ‘fall back’ position either until they married or if (God forbid), the marriage didn’t work out.

I hadn’t had any female teachers that inspired me until Mrs. Prince in 12th grade AP Biology. So, although I had no desire to become a writer–Mr. Holtby scared me–I decided I might become a halfway decent science teacher.

Nobody ever told me I couldn’t make the grade. The opposite. If I got a B on an exam, I saw “What happened?” scrawled across the top of the paper.

Thanks for this post. Reminded me to stop and give a prayer of thanks for the good people I’ve had in my life who influence positively.

I’ve been fortunate to not have nightmare experiences such as you describe. It’s job enough just weeding through a normal critique to find out which parts of the critique you accept and which aren’t in line with your story’s goals.

Instead, I give shout out to folks like grade school teacher, Mrs. Seese, who encouraged me from a young age to write. Mr. Shaffer from high school. And I still have a sweet complimentary & highly encouraging note I received from an instructor in community college on an honors project I worked on. So thankful for these encouragers.

I don’t see the point any anyone prognosticating about someone’s future success in writing. Just stick to honest evaluation of the content. It’s up to the writer to take it from there. And what counts as success is different for each writer.

I never had this experience with a teacher, but I recently had my manuscript critiqued blindly through a writing organization I’m part of. I’ve done plenty of manuscript swaps and I’m in a critique group, so I invite critique. BUT…this person flat out said my manuscript wasn’t marketable because childhood sexual abuse is mentioned in the protagonists past. I disagree. I’m reading a book now that has that very thing in it, along with some detailed physical and emotional abuse. Clearly my book wasn’t this person’s cup of tea, and probably not the genre I write in. I look forward to the day I’m published and prove this person wrong, not that I know who they are. I often wonder if they would have said that if the critique wasn’t anonymous. I think you can give a professional critique providing suggestions and things to think about without flat out crushing someone’s dreams. I would never flat out tell someone their book isn’t marketable.

It’s a common problem with critique groups that people with no real knowledge or experience end up parroting to their colleagues the “rules” that they’ve heard from others who have no knowledge or experience. I’m not against such groups in general, but it’s important to shop carefully for a compatible group.

Also, in critique groups, the members are partial to what rewsonates with them. It’s why self styled literary types look down their noses at storytellers like Mickey Spillane.

I would never bet against a m/s being a success. I’ve seen contest winners and Pullet-Surprise winners and best sellers that were, let us say, less than perfect. You never know what will resonate with readers, reviewers, or publishers. The luck factor is huge.

Many people in my early life encouraged me, from an elementary teacher who wrote “A creative child with a vivid imagination” on my report card to my wonderful parents who told their children to pursue their dreams. The worst that could happen, they said, was that you’d be back where you were when you started, but you’d have the experience and learn from it.

I got married as a teenager, horrifying my parents, who expected all of us to get degrees, but still had the stories in my head. I mentioned once to my mother-in-law that I thought I should be a writer. She laughed at me and said everyone wanted to be a writer, that even she had sent something to Reader’s Digest and they hadn’t published it. I’m ashamed to say I let her comment bury itself deep inside me and got regular jobs. I did keep writing, but until my husband encouraged me, I didn’t have the nerve to submit. When my first book was published, my mother-in-law showed up at every book signing, chatting with people in line, making sure they knew I was her daughter-in-law. I had something published in Reader’s Digest, too. Not much, but my name was on it. I’m sure she’s never seen the irony.

You know what they say: You don’t just marry your spouse, you marry your spouse’s family, as well.

When I first started writing, I entered my first chapter in contests. I got everything from “this is great!” to your heroine is TSTL (I looked it up–it meant too stupid to live). This particular judge went on to show me other mistakes I’d made. Long story short–I learned more from her critique than I did all the “this is great” judges. She told me to read Plot and Structure by James Scott Bell.

Now I judge a lot of contests where entries run the gambit of this should be published to “reads like my early stuff.” On the latter, I point them to JSB’s books on craft, encourage them to study his books and to keep writing.

Brenda nailed the essence of critique: “Just stick to honest evaluation of the content. It’s up to the writer to take it from there. And what counts as success is different for each writer.”

Miss Parker, my third grade teacher, championed my writing. When my first book was published in 2017, I tracked her down, called her, and told her what her encouragement meant to me. After teaching for 50+ years, she clearly didn’t remember me but appreciated the call.

When I give critique, esp. to young writers, I’m always mindful of the heavy responsibility I’m entrusted with. I never want to be the monster you describe, John.

Looking back, I see him less as a monster than as a cranky, bitter old man who took a job he didn’t want as a means to have someplace to live.

Coming out of the SF/Fantasy writing world, I’m familiar with him and the damange he wrought—I’m sorry that was inflicted on you.

I’ve been blessed—I had a number of teachers and writers who encouraged me. I had one that had their own aspirations of literary greatness and was bleak in their outlook about writing, but did not inflict that on me or their students.

My mentor Mary Rosenblum, who later became my editor, greatly encouraged me in my writing and also emphasized the need to overcome my fears around writing, something she noted many have. She passed away in 2018 but her encouragement and insights are with me, always.

Good post, John. I’ve been on both side of the wall. Had my first book savaged by Kirkus (the one you gave me a great blurb for!) and had one critic write of my romance novels, “She aims low and hits the mark.” Neither bothered me enough to crush my soul (but gee, I still remember them right?). As you say, good criticism should be tough but administered with the hope that the writer will learn.

On the other side, before I wrote crime fiction, I spent 18 years as a dance critic. Saw every major and minor company in the world and all the great lights and lesser ones. My first assignment was the review the New York City Ballet then on tour to Palm Beach. Gulp. I tried very hard, when the product on stage wasn’t great, to be kind in how I talked about it. And I always tried to explain my reasoning. Especially when I was there in the early birthing days of the Miami City Ballet. (Which then, wasn’t quite on par with NYCB).

I always followed this rule: Review something for what it is, not what it is not. And don’t crush those souls. They are laying themselves bare for you.

By the way, didn’t you win an award from ITW for the most obnoxious review of your stuff? I always coveted that award.

Hah! You remember! A newspaper in New York State wrote of NATHAN’S RUN: “The glue boogers in the binding are more captivating than Gilstrap’s torpid prose.” To this day, it’s the only review from a quarter century ago that I can still quote verbatim.

“Did you have teachers or coaches or bosses who inspired you to do things you never thought possible?”

“Short” answer, yes. The one that comes to mind is my creative writing professor at the local community college. I took the class as an adult. The prof was short on one end, so sometimes he would stand on his chair to teach.

But what a guy! One of the most entertaining and encouraging teachers I have ever known. He gave me an “A” on the last project, a short story we took all semester to write. Wrote on the top, “This is good. Don’t stop…”

I think I mentioned the story here at TKZ awhile back, that he was diagnosed with cancer years later and became a patient at the cancer center where I worked. I’d just published my 2nd book, I think, and brought a copy to work one day when he had an appointment. I gave it to him, and the look on his face was priceless. He died shortly thereafter. I’ve always been glad I had that opportunity to give back. 🙂

What a touching moment that must have been for both of you.

My experience was sort of opposite to the one you wrote about, John. When I was in high school (11th grade if I remember correctly), we had just finished a writing assignment when my English teacher asked me to stay after class. I was a shy, nerdy girl and had no idea why she wanted to talk to me. She told me she thought I could make some money with my writing.

I liked writing, but I loved math and, later, computer science, and I followed my left-brain lead into those fields. I simply didn’t have that burning desire to be a published writer that some people have at an early age. That longing seems to be part of what it takes to be successful. Like others have said, it’s okay to critique the writing, but not the writer.

One of the reasons I left teaching was that a special snowflake complained to management because I mentioned problems with her manuscript and suggested possible fixes, and her feelings were hurt. Management essentially told me not to give any criticism, and the adult students were told to go to them with any problems. The nonsense goes both ways.

To be clear, I would never complain to the administration for something like this. Of course, back then, no one would have either listened or cared.

I was thinking about some of my teachers today. High school was over 40 years ago. Things were different. Mr. Longo inspired a great many of us to do our best and enhance my love of history and research.

It’s truly disheartening to witness an attack on such an exceptional teacher and mentor, who garnered universal admiration from numerous students at institutions like William and Mary, in Texas, and at UC Irvine. He also positively impacted hundreds of other mentees over the years.

During Avram’s tenure at William and Mary, I had the privilege of knowing him. Conversely, you had a reputation for being entitled, challenging, and antagonistic. When discussing such matters, it’s important to present a balanced perspective. Avram extended a significant favor to you, for which you should remain deeply appreciative. That’s just my two cents.

I don’t think I know who you are. I don’t remember any Jenny in the class. I remember Jade, Brie, Rosemary, Bruce, Lindsey, Gerry, and Glen, but I don’t remember a Jenny. It’s been a long time, so I could be wrong. (Test: with what poem did he start every session?)

I had a reputation? Who knew? I was the entitled guy who lived on campus, couldn’t afford a fraternity and cashed a check every Friday for the $15 that paid for food, entertainment and dates for the entire week. (Thank God for George’s Restaurant–$1.69 for entree (chopped steak with onions and gravy), vegetable, potatoes, a roll, drink and dessert.)

I’m not sure what challenging and antagonistic mean in this context, but I’ll concede the point for the sake of argument. He wrote sci/fi and enjoyed what I guess we now call speculative fiction. (Lots of words and images, very little action.) I was 19 years old and trying to write a thriller. He simply didn’t like what I wrote, and that’s fine. That’s no excuse for his approach with me. For what it’s worth, I acknowledge him in NATHAN’S RUN for giving me something to prove.

As his godson wrote to me, “Avram was an incredible writer and a doting godfather. I also know he could be difficult. I am sorry that you had to see that side of Avram. He had falling outs but seemed to patch most of those up. I wish he had with you. Days before he died he had been sending out apologies to many he had wronged.”

Engaging in self-reflection is indeed a valuable practice. It’s worth acknowledging that he had his challenges in dealing with family, friends, publishers, and agents. However, he consistently displayed kindness towards children and students. He recognized that you possessed writing talent; Still, he had little patience for those who couldn’t take critique. Admittedly, he wasn’t flawless, but, to be fair, you were the only student in the class / his classes who faced such issues.

In the spirit of reflection, I leave you with the words, “Hear the voice of the Bard!”

Avram would have been very proud of you.

Aha! You pass the test! I’m sorry that I don’t remember you from the class. So much of those sessions confused me. How he loved it when Lindsey would include staves of music in the middle of a paragraph, and all I could see was a story that stopped dead. Some of the images from Glen O’s BLUE GHOST manuscript are still seared in my mind. (He just passed away last year, unfortunately.) Gerry W’s gorgeous descriptions of nothing happening.

The biggest takeaway from those two semesters was the realization that to succeed in any creative endeavor, one cannot depend on any outside help. It’s great when it’s there, but it has to be weighed against competing priorities. You’re ultimately on your own to make creative decisions. Avram’s commentary, especially at the end, when we were alone in his apartment for the final talk, reinforced my oft-learned lesson that you never wince when you get hit because it only empowers the other guy. I would like to think that he’d be proud, but I think he dismissed me so thoroughly that he would have no memory of me.

Now, a word from William Blake:

Hear the voice of the Bard!

Who Present, Past, & Future, sees;

Whose ears have heard

The Holy Word

That walk’d among the ancient trees,

Calling the lapsed Soul,

And weeping in the evening dew;

That might control

The starry pole,

And fallen, fallen light renew!

“O Earth, O Earth, return!

Arise from out the dewy grass;

Night is worn,

And the morn

Rises from the slumberous mass.

“Turn away no more;

Why wilt thout turn away?

The starry floor,

The wat’ry shore,

Is giv’n thee till the break of day.”

I’ve saved this: “…to succeed in any creative endeavor, one cannot depend on any outside help.”

It helps when it seems as if you’re making NO splash in the pond. And the work is, as usual, hard.

But you decide what you put your name on.

One day when I was in high school I was going with my mother to a fancy party. My mother told me to wear my blue jean jacket. It seemed odd, but mom said so, so OK. I asked her why?

My athletic letters were sewn on my jean jacket. The doctor who told my mother I would never be athletic was hosting the party. She wanted to make sure he saw the two sport athlete who would, “never be good at sports.”

Perfect! Moms rule…

This sounds a little melodramatic but I guess real life delivers such moments on occasion. My mother passed away last summer. I was looking thru old photos to share at her funeral and came across a long forgotten stack of papers from my college creative writing class. My professor. Ghita Orth had added a handwritten note full of feedback on my last assignment and some encouraging words. The last time I had spoken to her at the end of the class she told me to keep writing. That was over 20 years ago. It wasn’t until I had that paper in my hand that I realized how much her encouragement had stayed with me.

John Gilstrap, I applaud your tenacity. You succeeded in spite of the soul destroying efforts of someone with a fiduciary responsibility to note areas of improvement without gleefully drawing blood. There is no excuse for that. None.

I lack your good graces. I was born and grew up in an area written up in Life Magazine as the murder capital of the US (on a per capita basis.) Something of a rough neighborhood. In high school I had a plan to escape; I was on track to become valedictorian and receive a college scholarship.

My plan was derailed by a teacher. My total raw scores for the class at midterm were twice that of the nearest competitor. Despite that, I got a “B.” When I asked how that could be, I was told she didn’t believe in “A”s. She wanted to leave room for me to work even harder and show improvement. I had a full course load of difficult classes and my time was carefully allotted to each one. There was no way I could steal time from other classes to give her what she demanded. There was no appeal. She had all the power and I had none, or so she thought.

If she wanted to engage in a contest of soul destruction, game on. She resigned a month later, unable to cope with an unrelenting stream of very bad luck. The last of which occurred when she slammed her desk drawer shut to get the class’s attention. It went over the edge of the stairwell and tumbled down. After crashing into hallway door, it flew off its hinges. The desk continued sliding across the hall floor into metal lockers on the opposite wall, sounding like a bomb blast echoing down the hallway to the office.

Other students were spared an encounter with this soul-sucking dementor.

I didn’t get the academic scholarship. Instead I escaped that environment by taking the indentured servant route. I sold 4 years of my life to the military during the Vietnam War. There they continued my education in practical “how to” matters.

I think this is a problem of bad teaching — in any field. I’ve seen math professors wave away their inability to explain a concept to someone by saying that “you either have a brain for math or you don’t.” This is total BS. Anybody can learn anything, unless they have a very specific disability. It might take you longer, and you might have to use some work-arounds to get there, but you will, in the end, be able to do that math thing that you wanted to do. And the next one will be easier. And the next one after that — even easier.

It’s not like wanting to be a teenage Olympic gymnast, where you have to have the right body type, be the right age, and also have been training since before you were born.

Writing is even more so. I can’t think of ANY disability that could keep people from writing. Stephen Hawking wrote. If you can’t type, you can dictate.

And, once you’ve written something, if you want to improve it, you can connect with critique groups, trade with other authors, or hire editors. And if the final result is STILL completely unreadable — well, as far as I’m concerned, 50 Shades of Grey was unreadable and it did VERY well. I find Finnegan’s Wake to be unreadable, and academics LOVE it. What’s unreadable to one person is the best thing ever to another. 1.5 billion people in the world can understand English. Even without translating your work, that’s a lot of potential readers. Even if 99.9% of people hate your book, that still leaves 1.5 million people who’d like it! Sure, it might be a little work to find them, but with the Internet, and all the special-interest communities out there, there are plenty of ways. Even if one person reads your book and gains some wisdom, or enjoyment, or a chance to see the world from a different point of view — you’re a success, and you’ve got talent.

But can you make any money if 99.9% of people hate your work?

Yes. Google “1000 true fans.” If you can find 1,000 people — just 1,000 out of 1.5 billion! — who love your work enough to send you $10 a month for your writing, you’re making $10,000 a month. That’s $120,000 a year. That’s a writing career to be proud of.

One of my college journalism professors told me I was never going to have a career as a journalist. Fortunately, I was able to easily ignore her because I was ALREADY GETTING PAID TO WRITE FOR THE LOCAL PAPER. But I’m still bitter about her comments! Why did she tell me this? I didn’t like her teaching style. I didn’t put any effort into my classwork. And I had a writing style that she personally didn’t like. After graduation, I went on to write for the Chicago Tribune, then was a war correspondent for a while, then ran a news bureau in China for a few years.

It might seem “kind” for a professor to tell you not to pursue your passion. Instead, I think it would be kinder for the professor to tell you what it would take to get from where you are to where you want to be, so you can see whether the effort would be worth it, compared to the other options you’ve got.

In writing, you can *always* get to where you want to be. You want to be a literary success? There are tons of “no-talent hacks” who ladle on enough literary devices to disguise their lack of ideas enough to pass muster with the literati. You want to sell? Add in sex, violence, horror, and hire a good editing and marketing team. Worst case, hire a ghost writer to sit with you and guide you through your first few books. Or just use ghost writers! Picking ghost writers is a talent in and of itself! Is it “cheating” to add unnecessary literary devices and pile in big words and metaphors or is it being “smart”? Is it “cheating” to add sex and violence? To use editors or co-writers? To have an affair with a celebrity so that people will recognize your name? Does it matter? Your name is on a book, and that makes you happy. And people read that book and enjoy it, and that makes *them* happy. Everybody is happy. There are no objective criteria for talent or “good” writing. So just relax and do what works for you.

Bad critics want to increase the quantity of books *they* like and decrease the number of books that they don’t like. They want to dissuade people from, say, writing the next 50 Shades, regardless of how much people might want to see more 50 Shades. That’s just evil. They’re making readers less happy and making authors less happy.

Good critics help readers discover new books and new authors that they would like that they might not have heard of before. They make readers happy. And they make authors happy by finding them new readers. These guys are superstars!