“There are 500 million people on Facebook, but what are they saying to each other? Not much.” — Elmore Leonard

By PJ Parrish

Elmore Leonard was trending big on my Facebook feed this week. Everyone was quoting, but mainly misquoting, his famous Ten Rules Of Writing.

True confession time, she intoned gravely, I have read only two Leonard books. (ten bonus points if you get that reference).

Leonard is one of those titans whose stuff has been part of my cram-course in belated crime education. But like all writers, I’ve heard that he’s the Picasso of crime fiction, whose dialogue, in the words of one critic, is “like broken glass, sharp and glittering.”

But do his rules hold up? Well, I think this is a good time to go back and take a look. And I’ll be the first one to admit, I have broken almost all of them.

1. Never open a book with weather. If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.

I opened my book Island of Bones with a woman so desperate to escape her killer that she took off in a skiff in the middle of a hurricane. But generally I agree with Leonard here that in too many books, weather is a metaphoric crutch meant to telegraph the hero’s conflict or a mood of foreboding. Hey, it works in The Tempest, right? In the play, the small ship atoss in a raging storm is a metaphor for the characters, high-born and low, all at the mercy of natural events.

2. Avoid prologues. They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

Sigh. Broke this one, too. In my book A Thouand Bones, I am telling the story of Louis Kincaid’s lover, Joe Frye. The entire book is a flashback to Joe’s rookie year but I felt I had to connect it to Louis, so I book-ended it with a prologue (wherein she tells Louis about a crime she committed ten years ago) AND an epilogue (wherein Louis accepts what she did). But again, I think prologues are usually unnecessary. They almost always indicate the writer is not in control of back story or the time element of their plot (linear is almost always best). Or the writer tacks on a prologue where he throws out a body to gin up suspense because the early chapters are slooooow.

3. Never use a verb other than ”said” to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with ”she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

Have broken this one, too. See no. 4. But if you’re into “grumbled, bellowed, snapped, begged, moaned” and the like, then I’m pretty sure that the stuff you’re putting between the quote marks isn’t up to snuff. And if I ever catch you using “he barked” I will hunt you down and bite you, she yelped doggedly.

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb ”said.” To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances ”full of rape and adverbs.”

Guilty again. I have used “whispered,” “shouted” and “asked.” But I always hate myself in the morning.

5. Keep your exclamation points under control. You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.

I hate exclamation marks! But yes, I have used them. Mainly when I have someone shouting. And what’s worse, I have probably written, “Get out of here!” he shouted.

6. Never use the words ”suddenly” or ”all hell broke loose.” This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use ”suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.

I have never used “all hell…” That’s really amateur hour, akin to “little did he know that…” But yes, “suddenly” has appeared in my books. I didn’t realized what a stupid tic it was until I re-read Leonard’s rules. Suddenly, “suddenly” looks really bad in my chapters. And I now see that the action feels more immediate without it.

7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly. Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories ”Close Range.”

We made this mistake in our first book Dark of the Moon. Set in the deep South, we felt compelled to drop some “g’s” and use some dumb idioms, and at least one reviewer took us to task for it. Here’s the thing: Dialect is hard on the reader’s eye. You can convey the feeling of it by judicious word choice, mannerisms, and sentence rhythm. We are in the process of preparing “Moon” for eBook and this has given us a second chance to go back and rewrite things. So y’all can bet we’re fixin’ to fix our mistakes.

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters. Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s ”Hills Like White Elephants” what do the ”American and the girl with him” look like? ”She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.

Whew. Finally, one sin I don’t commit. I am a strong believer in less is more when it comes to character descriptions. I think if you tread too heavily in the reader’s imagination, you stomp out some of the magic from your book. Here is how I let readers know what my heroine Joe Frye looked like:

She had a flash of memory, of sitting next to her dad in a gymnasium during her brother’s basketball game, watching the cheerleaders.

I’m ugly, Daddy.

You’re beautiful.

Not like them, I’m not.

No. They’re easy to add up. They’re plain old arithmetic.

So what am I?

Geometry, Joey. Not everyone gets it.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things. Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.

This one is hard for me because I love to write setting descriptions. But I have learned to pull back some. The best advice I ever heard on this comes from Coco Chanel who said you should put on all your accessories and then take all of them off except one before you go out. So yeah, I over-describe but then I go back and take off the pearls and leopard hat.

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.

Like all writers, I struggle with this one. When we’re deep in the writing zone, we can fall in love with the sound of our own voices. And sometimes, a passage will come so hard that you just can’t bring yourself to delete it. But you must kill your darlings. Lately, I feel myself “underwriting,” so maybe I am pulling back too far. But I still think it’s better to leave ‘em wanting more, not less.

11. If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

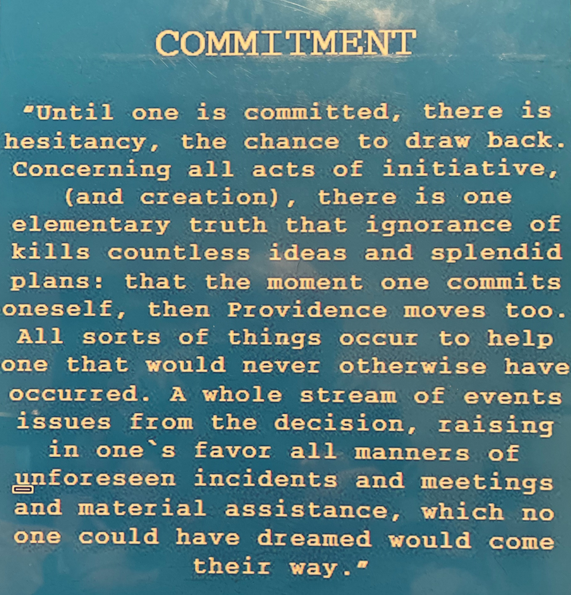

I have nothing to add to that last one. It might be the single best piece of writing advice out there. If you’re working too hard, your reader will as well. Here’s the quote that hangs over my desk: “Easy reading is damn hard writing.” It was good enough for Nathaniel Hawthorne — and Leonard — so it’s good enough for me.

Phoebe ready for trick or treating

Postscript: I am en route today from Michigan back to Tallahassee, two dogs in tow. If I don’t answer to your comment it is probably because I am somewhere over Cinncinati or stranded in Big Daddy’s Burger Bar in the Charlotte airport. Happy Halloween!