Paragraphing is a way of dramatization, as the look of a poem on a page is dramatic; where to break lines, where to end sentences. — Joyce Carol Oates.

By PJ Parrish

Yesterday, Sue posted her critique of a First Page submission. Click here to review. On first read, I thought it was pretty good but something about it was bugging me. Then I just looked at it instead of reading it. It hit me that the paragraphing wasn’t quite right.

Paragraphing? Who cares about paragraphing? You just hit enter when it feels right, right? Nope. Proper paragraphing is one of the most underrated tools in your writer’s box. So allow me to wander into the weeds today and talk a little inside baseball. (I worked hard on that mixed metaphor, by the way)

Two main problems with the submission yesterday: The writer had made the common mistake of burying thoughts and dialogue within narrative.

Second problem: All the paragraphs are about the same length. Why is that a problem? Because it goes to pacing and rhythm. No variation in paragraphs is boring to the eye and that translates to boring for the reader’s imagination. But if you learn to master the fine but subtle art of judicious paragraphing, you can inject interest and even tension into your story.

Let’s address problem one first. This opening paragraph is essentially narrative. But inserted within that is both dialogue and thoughts. Here’s the paragraph:

Arizona Powers slammed her palm into the office wall, ignoring the stinging sensation. Unbelievable. “Are you kidding me? I’m not doing that. I’m a federal agent, not a babysitter.” Her boss had clearly lost his mind. She spun on her hiking shoe, locking eyes with Senior Special Agent Matt Updike. Her fingers fidgeted with a button on her shirt. I deserve a second chance.

Dialogue and thoughts are ACTION. They deserve to be lifted out of narrative and given lines of their own so the reader can emotionally latch onto them, and by extension, your character. This opening paragraph would be more effective (and more interesting to the eye) if it were deconstructed with better paragraphing:

Arizona Powers slammed her palm into the office wall, ignoring the stinging sensation, and stared hard at her boss.

“Are you kidding me? I’m not doing that. I’m a federal agent, not a babysitter.”

Matt Updike shoved his chair backward, rose and closed the distance between them in two strides.

“I’m not kidding. You are doing this,” he said. “You don’t have a choice.”

She could smell his stale coffee breath and see a vein bulging in his neck, but she resisted the urge to step back. Her boss had clearly lost his mind. But she wasn’t going to take this. She deserved a second chance.

See the difference? The drama of the scene is enhanced by allowing the thoughts and dialogue to stand out — all by simple paragraphing. Here’s something interesting: The rewrite is LONGER but it reads FASTER. Why? Because the reader doesn’t need to ferret out the important thoughts and dialogue. It’s your job, as the writer, to mine out the nuggets for them.

Now let’s consider the basic question of length of paragraphs and how that affects your reader. How long should your paragraphs be? Sounds like a dumb question, but it’s not. You need to consider it deeply.

About five years ago, I did a very long post on paragraphing with a lot of examples, Click here if you want to review. But let me re-quote this from Ronald Tobias’s The Elements of Fiction Writing: Theme & Strategy,

The rhythm of action and character is controlled by the rhythm of your sentences. You can alter mood, increase or decrease tension, and pace the action by the number of words you put in a sentence. And because sentences create patterns, the cumulative effect of your sentences has a larger overall effect on the work itself. Short sentences are more dramatic; long sentences are calmer by nature and tend to be more explanatory or descriptive. If your writing a tense scene and use long sentences [me here: or long paragraphs], you may be working against yourself.

I often liken writing to music. Composers use punctuation to speed up or slow down pace and musicians use types of “articulation” to enhance whatever mood they are going for — intense? dangerous? romantic? thoughtful?

Good writers use similar tools — punctuation, length of sentences and paragraphs (short and choppy or longer and measured?) to create an emotional response in their readers. The best writers understand this not only creates emotion, it provides variety on each page and over the whole book.

Pacing is not just aural, it’s visual. How your writing LOOKS on the page is important. Which brings us back to the paragraph. How many you use per page, and how long or short your paragraphs are should be conscious choices you make. Here is the same thought, expressed two different ways:

Fragments, the length of sentences, punctuation, and how often you paragraph can all work to give a particular pace. If you really think about, you’ll realize that you can use sentence and paragraph structure to create a feeling of speed or slowness, depending on what kind of emotional response you want to induce in your reader.

Okay, that gets my point across, right? But what if I structured the same thought this way:

Think of it! You can move a reader through a story fast. Their hearts will race!

Or you can slow them down and make them use their heads.

It’s all in how your sentences look on the page.

The first is measured, more academic in pace, meant to make you slow down and digest the thought. The second is lively and urgent, making you anticipate an important climax-point. Neither is correct. They are just two different styles of pacing, word choice, sentence length and paragraphing to different affect.

I think most of us here, being in the crime business, know we shouldn’t write a lot of long paragraphs. You can get away with some, especially in description. But these days, too many long paragraphs per page looks “old-fashioned” or worse, “textbook.” It worked for Dickens and even for a stylist like Delillo. Not so much for the rest of us today.

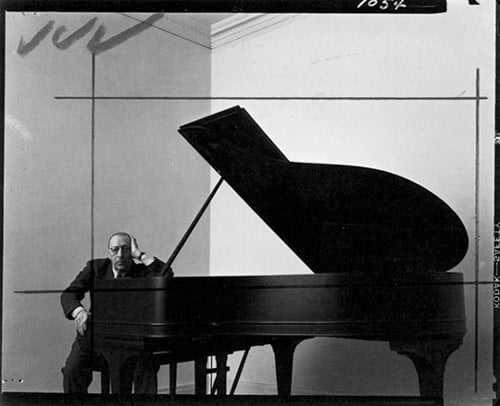

Are any of you out there art folks or designers? Then you understand the value of “white space” or “negative space.” Simply put, negative space is the area around and between a subject. It appears in all drawings, paintings and photographs. The “subject” below is enhanced by the negative space surroudning him. (Notice, too, the crop lines that make for an even more compelling negative/positive composition!)

Paragraphing provides white space. Don’t believe me? Go read Elmore Leonard.

Ray Bradbury said that each paragraph is a mini-scene and when you hit ENTER you are helping your reader enter a new scene, thought or action. I’ll leave you with one more example. It’s from one of my favorite opening pages from a novel.

It was a pleasure to burn.

It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon-winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning.

Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame.

That’s the opening to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. I love the way the first line sits there all alone, like a roadside sign that you’re entering hell. Then he gives us this amazing loooong graph with gorgeous imagery and the nonchalance of the unnamed man. And then, a third paragraph — BAM! — he gives us our arsonist-star by name.

Bradbury could have made this all one graph. But no, he chose three. Your turn. Choose wisely when to hit enter.

Excellent, and good timing as I’m going through the wip before sending it to my editor. I think this is why “literary fiction” is so hard for me to read. It’s often very dense, with little white space.

Back in my submitting to agents/editors days, I had an editor say she could glance at a page and judge the pacing of the story. Lots of long paragraphs meant it was slow, and often rejected just with that look.

I also remember your words: “Don’t bury your dialogue.”

Interesting comment from the editor, that she can sense the pacing just by looking at a page. I find myself doing the same thing as I decide whether or not to delve into a new book. I don’t mind a longer narrative but I want to be sure the writer understands the beauty of good pacing.

Like Terry, this is perfect timing as I go through my manuscript. I was having a problem with a conversation between h/h and it was stilted. After reading this, I know what the problem is! I buried some of the dialogue. Thank you!

Now off to read your previous post on paragraphs.

It was long. Could’ve used more paragraphs. 🙂

Excellent point, Kris. Paragraphing and sentence structure makes all the difference. I’m attracted to certain authors by the way their words sing. If the rhythm is off, I feel it right away. One of the most powerful words is…

Run.

All by its onesie. If it’s jumbled into a long paragraph, it loses its power. And so does…

Blood.

Everywhere.

I was going to mention the power of one-word paragraphs too, Sue. Great minds…

Yeah, for sure! Am a big fan of one-word paragraphs!

Great timing.

I’ve been thinking about paragraphs a lot as I get my ms ready to send out to agents, and my story definitely reads differently with many short paras rather than longer ones.

Going back to read your previous post on the topic, thanks!

My rule, implied above, is: One speaker per dialogue paragraph, one actor per action paragraph, where possible.

Pacing is also a function of content: complex action, description, and dialogue impede the reader. Reword them as needed to minimize all three, particularly in action passages, such as fight scenes. Omit unneeded detail!

Another thing that can retard the reader is many diverse consonants, particularly when reading aloud. Trying to wrap your mouth or brain around tongue-twister phrases is a challenge, as in: “We face a Brobdingnagian conglomeration of polysyllabic verbosity, Joe.” The solution is to use short and alliterative pairs of words, where feasible: “We’re working with a huge passage of turgid prose, Ted.”

And note that anything done too often or too long can irritate the reader.

Did you work hard to make up that awful line, JG? Loved it.

Ha-ha, yes! But today I borrowed it from my blog post on studying acting to enhance screenwriting.

https://jguentherauthor.wordpress.com/2014/12/21/20-scriptwriting-tricks-from-an-actors-pov/

I’m a big fan of white space on a page. Ever since a news writing class in college, I hit “enter” early and often.

Well, I hadn’t thought about it til you mentioned it, but yeah, I guess my background in newspapers helped me to understand this for fiction. Pretty much, one thought, one graph.

Paragraphing was the first thing I noticed yesterday, but for some reason couldn’t put it in words. 🙂

How I punctuate my sentences is purely based on rhythm. Audiobook narrators says that a quick pause is a comma, a two-count pause is a period, and a threecount pause is a paragraph break. As I write, I hear the words in my head, so whenever I pause, I punctuate. These might change later, but it’s still based on rhythm.

Another thing I do for paragraph breaking is to decide whether I want the reader to remember the last words of a sentence or not. Mary Robinette Kowal talks about primacy-recency, which means that the reader remembers the first thing in the paragraph and the last. If you want to hide something, put it in the middle. But if you want them to know something important, put a paragraph break.

This comment ran long.

Love that idea of primary/recency. Might steal that for future post. And your comment might feel long but it’s well-paragraphed. 🙂

I just did a search for the primacy-recency effect, and apparently it’s a psychology term.

We trial lawyers learn all about primacy and recency when arguing to a jury.

Is that like telling em what you’re going tell em. Tell em. Then tell em what you told em?

Exactly, with words that resonate.

I did find a teaching video where she mentions this, but only in passing. It comes around the 15:45 mark. Basically, she means that deliberate repetition of a word, phrase or image can be an effective writing tool.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cc31v46TTLk

Kris, great post! Paragraph length is so important and so often ignored. A writing teacher once told me, “White space is your friend.”

As Azali pointed out, the first and last sentence of a paragraph are what people remember most. When I want to slip in a significant clue that I hope the reader doesn’t notice, I bury it in the middle of a long paragraph.

It’s there, hiding in plain sight, inconspicuous.

When the big reveal happens, the reader thinks back and realizes, “Oh, that’s why.”

It’s often good to save that great line for the last line in your chapter. It’s a good way to get them to turn the page.

This is very helpful, Kris. I often think about the rhythm of my words, but hadn’t considered the way the words look on the page. However, I noticed something recently that applies to this.

I was reviewing my latest book before uploading the final version to the retail sites, and I noticed a page where there were two sequential paragraphs, each of just one sentence, and the sentences were the same length. It looked odd. I didn’t make a change then, but I will now before I do that final upload.

I’ve used paragraphing a lot in my fiction, but more intuitively, without thinking it through as much as I should. The same goes for sentence length. (I’m also too fond of simple declarative sentences, but that’s a separate issue 🙂

Thanks for this keeper of a post!

Thank Sue for her critique yesterday. As I said, I liked the submission but something about it was bugging me. Didn’t realize what it was until I went back and read it a couple more times.

As I read this paragraph, I wondered if more emphasis should be put on the last line, so I put in an extra paragraph.

She could smell his stale coffee breath and see a vein bulging in his neck, but she resisted the urge to step back. Her boss had clearly lost his mind. But she wasn’t going to take this.

She deserved a second chance.

I like that even better!

Thanks. 🙂

In ancient times, when ebooks came into being, I realized that long paragraphs that look great on paper, stink on an ebook reader or a phone. They are massive blocks of text that seemed to go forever. After that, I started making my paragraphs shorter if I could.

Readers have also gotten so lazy that they balk at long paragraphs even on paper. White space is even more important, today.

Hadn’t considered the eBook factor but just went and looked at a book on one and you’re right….it really jumps out at you.

How do you feel about dialogue in the middle of a paragraph? I can’t find any examples from my first draft (probably because I’m trying to avoid it), but I see it in some of the fiction I read.

Character X does something, and it goes on for a couple of sentences. Then X says something that may or may not be related to what they just did. Then there’s more action, and maybe another word or two of character X talking.

Dialogue in a paragraph of narrative? Not a big fan. It can work in very limited cases, I think. If it directly relates to an action previous. Maybe like: He walked up to the woman and held out his hand. “You don’t want to do this. Give me the gun.”

But otherwise, I’d go with letting the dialogue, especially if it’s juicy, stand alone. Here’s an example and a rewrite:

Harry sauntered up to the man and pointed his gun at his head. “You’re thinking ‘Did he fire six shots or only five?’ Now to tell you the truth, I’ve forgotten myself in all this excitement. But being this is a . 44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and will blow your head clean off, you’ve gotta ask yourself a question: “Do I feel lucky?” Well, do ya, punk?”

Might it not be more “readable” if structured thusly, with dialogue standing alone and three paragraphs instead of one?

Harry saunted up to the man on the ground, gun down at this side.

“You’re thinking did he fire six shots or only five?,” Harry said. “Now to tell you the truth, I’ve forgotten myself in all this excitement. But being this is a . 44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and will blow your head clean off, you’ve gotta ask yourself a question: Do I feel lucky?”

Harry raised the gun and pointed it at the man’s head. The man stared up at Harry with wet wide eyes.

“Well, do ya, punk?” Harry said.

(I watched Dirty Harry the other night.)

Just re-read your question to see if my answer was helpful. Need to add one more thing: If the character speaking the dialogue changes, definitely you need new paragraphs. Each time the speaker changes, hit enter. 🙂

Thanks. I agree with you. Great example. 🙂 And yes about starting a new paragraph for a new speaker.

Thank you for this great post. I have been struggling with this matter for a long time. Given that dialogue and internal thoughts (the italicized kind) are action the deserve their own paragraph. I’m still confused if action beats would be treated the same way.

For example, if speaker one has a line of dialogue followed by speaker one’s action beat, it seems reasonable that those could both go on the same line. However, if speaker one’s dialogue is followed by person two’s action beat would the correct formatting be to put them on separate lines? I feel like it would. Does this also apply to internal monologue and narrative?

Not sure I QUITE understand your question, but let me take a swing. By action beat, I think you mean something physical the speaker does? Example:

“I have been waiting for you all night,” Tom said. He pushed himself out of the chair and trudged toward the window, peering down on the street below. “Now I don’t give a damn,” he said softly.

I think if you keep your dialogue and action beats short, you can join them in the same graph. But if the dialogue or action beat is extended, the reader’s eye might need some relief. It’s something you have to develop a feel for as you grow as a writer and find your style.

If in doubt, I’d opt for shorter graphs.

Thanks for the explanation. Yes, it’s usually something physical the character does. Sometimes it can replace a dialogue tag:

I stepped in Tom’s path. “I didn’t think you’d show up.” I kept them in the same graph because I have the action and I have the line of dialogue.

What I meant is more like this:

“Sit in that chair and don’t move,” I said.

Tom eyed me suspiciously.

“And don’t move the chair either.”

Did I really need a new graph for Tom’s action beat to make it clear to the reader that it’s me talking and Tom ‘eyeing?’

I ask this because I frequently have a couple lines of dialogue for person A, followed by a short action beat by person B, followed by a couple more sentences of dialogue by person A. I often feel that when I break it into separate paragraphs, I owe the reader some descriptor (I continued, …) to let them know it’s still person A speaking.

Thank you for the excellent insight & the timeliness. I’ve made a note to come back to this post when my co-author & I get our feedback from the betas and begin revisions.

Found it interesting that when *reading* fiction I don’t tend to pay attention to the nature of the paragraphs I’m reading (i.e. do they all tend to be long, etc). Perhaps this is because I read on an e-reader vs. a print book. But I do tend to notice this at times when re-reading my own work so I know it’s an area for improvement.

I also wonder if, when someone reads a few pages of your work and comments that it feels literary, that they are really honing in on issues like long paragraphs that make the read more slow and plodding. Hmmm…

Much to think about. Thanks.

This is why I ALWAYS print out my work on read it on paper. There is something about seeing an actual “page” that makes the paragraph issue jump out more clearly.