“For God’s sake, don’t write unless you have to….It’s not easy. It shouldn’t be easy, but it shouldn’t be impossible, and it’s damn near impossible.” – Frank Conroy

Discuss!

“For God’s sake, don’t write unless you have to….It’s not easy. It shouldn’t be easy, but it shouldn’t be impossible, and it’s damn near impossible.” – Frank Conroy

Discuss!

Rita, my wife, manages cashiers at a mad-dog, inner-city supermarket where going bananas from loose cannons is the norm. “It’s like herding cats,” Rita says about her staff, although she knows every cloud has a silver lining, and Rita says, “I also fight an uphill battle with bat-crap crazy and cold-as-ice customers who drive me nuts.”

At the end of the other day, Rita came home and vented—as usual. I’m her sounding board, but I have selective hearing so often, with me, it’s beating a dead horse. Rita went on to tell me about this, that, and other things going on in her shift.

Then she asked, “Ever hear, ‘When the cows come home to roost’?”

I looked up, smiled, and replied, “No. But it’s a clever play on clichés. Where’d you hear that?”

“A regular customer and I got in a Covid conversation. He’s sick of the mask thing. The double vax and now the third. And Stop! Show me yuh papuhs, as if we’re in Nazi Germany. So am I. Then he says, ‘Well, at the end of the day, when the cows come home to roost, catching Covid boils down to this. You’ll live happily ever after or you’ll give up the ghost.’”

———

Rita’s regular customer got me thinking about clichés.

Growing up in small-town Manitoba, Canada, was cliché emersion. I could go on and on with local cliché examples like “Pissed as a nit, liquored as Larry the Lizard, and drunk as a skunk”. Life in the fast lane was, back then, alcohol-fueled.

How often do we say clichés in daily conversation? How often do we write them—subconsciously—into our WIP and fail to recognize these easy-as-pie, easy-peisie, sneaky snips of syntax? How often do we miss clichés only to catch a few in the nick of time before we hit the publish button that can bring the perfect storm—that can of worms—of bad, bad reviews?

I did a little Googling on clichés. The Wonderful World of Wiki had this to say:

A cliché is a French loanword expressing an element of an artistic work, saying, or idea that has become overused to the point of losing its original meaning or effect, even to the point of being trite or irritating, especially when at some earlier time it was considered meaningful or novel. In phraseology, the term has taken on a more technical meaning, referring to an expression imposed by conventionalized linguistic usage.

The term is often used in modern culture for an action or idea that is expected or predictable, based on a prior event. Typically pejorative, “clichés” may or may not be true. Some are stereotypes, but some are simply truisms and facts. Clichés often are employed for comedic effect, typically in fiction.

Most phrases now considered clichéd originally were regarded as striking but have lost their force through overuse. The French poet Gérard de Nerval once said, “The first man who compared woman to a rose was a poet, the second, an imbecile.”

A cliché is often a vivid depiction of an abstraction that relies upon analogy or exaggeration for effect, often drawn from everyday experience. Used sparingly, it may succeed, but the use of a cliché in writing, speech, or argument is generally considered a mark of inexperience or a lack of originality.

When I think of clichés, I often grin at how badly sports stars cliché in their media interviews. Take the golfer, “Yeah, just gotta keep the head down, eyes off the leaderboard, stick to the process, and let the putts drop.” Or the hockey player, “We gotta bring our A-game, give it a hundred ten percent, keep the other team on the boards, and get pucks to the net.”

But what about us common-place writers? How regularly do clichés slip into our WIP and how hack-like does that make us sound? Writing gurus say using clichés shows a lack of original thought, makes us appear unimaginative, and unmask a lazy writer.

I did a little more Googling and found some defense for clichés. One article said it was okay to use clichés when you’re trying to sync with a readership and use familiar phrases like back in the day for Boomers and the struggle is real for Millennials.

The article also said clichés were great to simplify things like explaining beginner concepts. It dropped an example of writing a how-to guide for expectant mothers. In this case remember, you’re eating for two was okay.

And the piece I found suggested clichés were fine, if not expected for dialogue and characterization. A fiction writer might use clichés to show a character’s sophistication level or their sense of humor. I’m wondering how when the cows come home to roost fits in with sophistication and humor. (Rita said the guy seemed dead-serious about it.)

I think we’re all somewhat guilty of dropping clichés. I know I am. Thankfully I have Grammarly Premium that tracks and highlights common clichés. You know, stuff like:

“The wrong side of the bed.”

“Think outside the box.”

“What goes around comes around.”

“Dead as a doornail.”

“Plenty of fish in the sea.”

“Ignorance is bliss.”

“Like a kid in a candy store.”

“You can’t judge a book by its cover.”

“Take the tiger by the tail.”

“Every rose has its thorn.”

“Good things come to those who wait.”

“If only walls could talk.”

“The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.”

“The pot calling the kettle black.”

“The grass is always greener on the other side.”

My cliché article gave a bit of helpful advice on avoiding clichés:

My last Google cliché search rabbit-holed me into the mother-of-all cliché pieces. It’s a great site that I’ve never stumbled on before called Be A Better Writer which I’d certainly like to be. However, this article’s well was just a little too deep for me. It’s called 681Cliches to Avoid in Your Creative Writing.

How about you Kill Zoners? On a scale of 1 – 10 (1 being cliché free and 10 being cliché down & dirty), how guilty are you of letting clichés slip into your work? And is there a time when it’s okay to use clichés? Oh, and can you make up a better cliché phrase than when the cows come home to roost?

——

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner—pretty much Doctor Death for over thirty years. Now, Garry is a caped crime writer who fights villainous words rather than crafty crooks and deadly stiffs.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner—pretty much Doctor Death for over thirty years. Now, Garry is a caped crime writer who fights villainous words rather than crafty crooks and deadly stiffs.

Check out books by Garry Rodgers on his website at DyingWords.net. You can also follow his bi-weekly blogs by hitching onto his mailing list and make sure you connect with him on Twitter @GarryRodgers1.

The Nose Knows

Terry Odell

When we learned to write (and it’s an ongoing process, so I shouldn’t be using the past tense), we were told to pay attention to using the senses. Most of us focus on sight and sound, but there’s another sense that can bring additional life to your writing–the sense of smell. Sure, we might mention it if a character walks into a restaurant, or stumbles on a dead body, but otherwise, it’s frequently left out of our writing, or not utilized except in passing. Elaine did an excellent post about this several years ago, with excellent examples, but I thought the subject would be worth another visit.

Why is the sense of smell important? First, it’s another way for readers to connect to our characters. It’s also one of our most powerful senses. A brief detour into basic biology. I’ll spare you a lot of the technical talk, and cut right to the chase. If you’d like to delve deeper into the physiology, I’ll leave links at the end of this post.

The part of our brain that processes olfactory stimuli (smells) is closely connected to both memory and emotional centers. The other senses, like sight and sound, make a stop at the thalamus, which is the main relay station for the brain. From there, they go on to their processing centers. Not so the sense of smell. Scents go straight to the olfactory bulb, the brain’s smell center. This center is directly connected to the amygdala, the center for emotions, and the hippocampus, which plays a major role in memory. No, there’s not going to be a test, but this explains why a smell can trigger a detailed memory or a powerful emotion.

Okay, so there’s scientific documentation that smells are linked to memories and emotions. Any writing connections? Marcel Proust explored the phenomenon in Swann’s Way, wherein his character is transported to his childhood after savoring a madeleine cake soaked in tea. These memory/odor connections are referred to as the “Proust Phenomenon”—the ability of odors to cue autobiographical memories.

Many of us could stand to do more with the sense of smell in our writing.

Characters should not only be noticing smells, but they should be reacting to them as well. Detecting an odor could mean danger. Smoke waking them up at night. Food that doesn’t smell ‘right.’ A character’s scent memories can be a way to introduce back story, or move the plot forward.

A reminder, too, that sensory details shouldn’t be used like a laundry list. They need to mean something.

While I don’t pretend to have any remote similarities to Proust, I do try to include the sense of smell in my writing. They’re not deep, or ‘beautiful prose’, but they add to characterization, or move the story along.

Show, don’t tell, so here are a few examples from my own work.

From Finding Sarah, when the inevitable romance plot ‘black moment’ has separated Randy from Sarah. Throughout the book, he’s noticed the scent of her peach shampoo.

Randy spent the next few days wallowing in his own misery. Feeling like a first-class idiot, he’d even gone to Thriftway and bought a quart of Peach Blossom shampoo, only to pour it down the drain after using it once.

From Nowhere to Hide. We get a hint of the kind of taste Graham has from this snip:

Deputy Graham Harrigan sat at his computer in the Sheriff’s Office substation, the normal sounds of office activity fading to white noise as he hunted and pecked his way through the report he needed to file. As he’d told himself countless times, he should take a keyboarding class so he could get through the drudgery faster. The smell of stale, burnt coffee permeated the air, and he wished he’d taken a few minutes to stop at Starbucks.

And, from the same book, a look into Colleen’s past

Colleen jerked awake, drenched in sweat and tangled in the sheets. She sat up and fought the nausea as the memories came back, crystal clear and in freeze frame, like a slide show from hell.

A domestic dispute. By the book, she and Montoya using all the right phrases: “Yes, Mrs. Bradford. You don’t need the knife. Relax, Mr. Bradford. I’ll take the bat. Let’s sit down. Talk to me, Mr. Bradford.” The tension lifting.

Someone on the stairs. “You bastard! You’ll never hurt my mother again.” Kid, late teens at best. Brandishing a gun. Shooting. So much shooting. The noise. The smells. Gunpowder. Blood.

Our brains are wired to recognize unfamiliar smells. They also acclimate to prolonged exposure. My husband never noticed the smells he brought home after performing necropsies on marine mammals. One nick in his glove, and I knew it, but he was oblivious.

Check your current work for scent references. One way is to do a search on words such as odor, aroma, wafted, scent, smell.

Many of our scent memories relate to childhood because that’s when we experience them for the first time.

What scent memories do you have? For me, it’s the smell of birdseed. My great aunt and uncle had an egg ranch (which meant they raised chickens), and when we visited, we’d help feed the chickens. I’m transported back there every time we open a bag of birdseed.

My references for this post beyond my aging memory of physiology classes:

Why do smells trigger memories?

Here’s Why Smells Trigger Such Vivid Memories

Why Smells and Memories Are So Strongly Linked in Our Brains

What about your characters? How have you used the sense of smell to add depth or move the story? Examples welcome.

Now available for pre-order. In the Crosshairs, Book 4 in my Triple-D Romantic Suspense series.

Now available for pre-order. In the Crosshairs, Book 4 in my Triple-D Romantic Suspense series.

Changing Your Life Won’t Make Things Easier

There’s more to ranch life than minding cattle. After his stint as an army Ranger, Frank Wembly loves the peaceful life as a cowboy. Financial advisor Kiera O’Leary sets off to pursue her dream of being a photographer until a car-meets-cow incident forces a shift in plans. Instead, she finds herself in the middle of a mystery, one with potentially deadly consequences.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

By Debbie Burke

Today, please welcome Rick Bleiweiss, Head of New Business Development for Blackstone Publishing. Rick is a former record company senior executive, Grammy-nominated producer, podcaster, and journalist. He is also the author of Pignon Scorbion & the Barbershop Detectives, a mystery set in 1910 in a sleepy English village, to be released in February 2022.

Rick Bleiweiss

…what I’m doing at 77 years of age [is] an example to other seniors that you are never too old to try something new or follow your dreams.

Debbie Burke: Blackstone Publishing is unusual in that they started with audiobooks then later added print and ebooks. Could you tell us about that shift and the reasons behind it?

Rick Bleiweiss: The decision to begin publishing books and ebooks in addition to audiobooks was made about seven years ago. We published our first books in 2015. It was primarily driven by three things.

First, the more popular audiobooks became the more other publishers held onto those rights, made their own audiobooks, and stopped licensing them to other companies, such as Blackstone.

Second, we felt that we could succeed well as a publisher of books and audiobooks and have those as another income stream. And we felt we could ramp up quickly as we already were evaluating manuscripts, involved with authors and storytellers, and selling and distributing audiobooks to many of the same buyers at accounts whom we’d be selling books and eBooks to. So that would make it an easy transition.

An added benefit of licensing all rights to a book – print, ebook, audiobook – is that we would be getting the audios, which would start making up for the ones we were no longer getting from some other publishers.

Third, the vision of Blackstone’s CEO (and owners) was to make Blackstone into more than just a traditional publishing company, but rather to turn it into a media company that has publishing and storytelling as its foundation, but also is involved in securing film & tv deals and being a media producer, creating intellectual properties, doing video games, comic books and magazines, and creating and selling merchandising. And we are doing all of that today and more, including owning our own printing plant so that we can make everything in house and never be out of print.

Regarding how we started our print program, early on we obtained the rights to the Max Brand and Loius L’Amour catalogs and signed a number of authors who had some past success but were not yet major sellers. Then it really kicked up a notch when I signed PC & Kristin Cast and we published the last of their books in their 12-million selling House of Night series. Then our CEO Josh Stanton and I got the James Clavell catalog, and I signed Natasha Boyd, who has had one of our biggest on-going books, the USAToday best-seller, The Indigo Girl. That was closely followed by signing Nicholas Sansbury Smith and his Hell Divers series.

DB: In 2019, Blackstone, a family-owned, independent press, made news by luring heavy hitters Meg Gardiner, Steve Hamilton, and Reed Farrel Coleman away from Penguin Random House. Without spilling any secrets, do you anticipate Blackstone’s further expansion of authors who may be disgruntled with the Big Five?

RB: Actually, they were not the first nor have they been the last, although they were major signings. I wouldn’t characterize it as disgruntled with the Big Five as much as wanting to go with a different publisher paradigm. Josh Stanton and I were able to license the aforementioned entire James Clavell catalog (including his classic Asian Series featuring Sho-Gun) and Gregory McDonald’s catalog (Fletch and Flynn series) both of which I believe had been with Dell for many years but whose estates were looking for something different. Other authors who we have signed to do print and eBooks who have also been with major publishers are Sherilyn Kenyon, Heather Graham, Catherine Coulter, Rex Pickett, James Carroll, Peter Clines, Andrews & Wilson, PC & Kristin Cast, Josh Hood, a good part of the Leon Uris catalog, Gabriel Garcia Márquez, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Al Roker, Eric Rickstad, Brian Freeman, Adrian McKinty, Orson Scott Card, M.C. Beaton, Matthew Mather, Don Winslow, Shelley Shepherd Gray, Catherine Ryan Howard, The Black Berets series and quite a few others.

I think that many people are starting to realize that we are expanding well beyond the role of a traditional publisher and that we are looking at what tomorrow’s successful media/publishing companies will be like and look like, rather than the traditional way of doing things. Hopefully, we have taken the best time-honored industry practices and augmented them with newer ways of looking at what a publisher can and should do. As an example, we have a head of film/tv who got deals for eight of our books within the last three months.

DB: Please describe a day in the life of Head of New Business Development.

RB: Fortunately, because it keeps my business life interesting, there have been many different things I’ve done in that role. I’ve bought other companies for Blackstone (such as the direct-to-consumer company, Audio Editions), licensed our technology to other audiobook companies, arranged distribution deals with other publishers, made introductions between Blackstone and high-profile tech and content companies, I am on Blackstone’s Board of Directors, I put together the relationship between Blackstone and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival which resulted in Grammy-winning audio versions of their Shakespeare plays, I co-created a series of books by Native American elders to preserve their wisdom, humor and teachings.

In short, I have had my fingers in a lot of different pies and strive to be one of the people at the company who keeps Blackstone moving forward as well as in new directions.

DB: What specifically captures your attention when you review submissions?

RB: Since the majority of the acquisitions work that I’ve been doing lately has been more focused on celebrities, best-selling authors and hit catalogs, rather than on debut authors, I look for different things now than I did when I was evaluating day-to-day acquisitions. When I did that, I would look to see if the synopsis intrigued me, if I thought the story was something that the public would be interested in, what the author’s background, social media involvement and overall commitment to being a writer were, and what our sales and marketing people thought they could do with the book. And, of course, finally, was the writing any good?

For an author who wants to submit a query to an agent or a publisher (and submitting to an agent is probably a way lot easier than submitting directly to a publisher) they should make sure to know something about each person they are submitting to so they can personalize each letter/email. The author has to make sure the genre they are submitting is a genre the agent or publisher works in. The query letter should also contain a short, but effective, synopsis of the story, the author’s bio, comps to other books, anyone they could get to endorse the book who would be meaningful, and, if possible, something that perks the reader’s interest and sets the query letter apart from the hundreds of others that the agent/publisher has received.

DB: Tell us about your own writing.

RB: When I was twelve, I hammered out the first two-page sports newspaper that I wrote on my old Royal manual typewriter and sold the two carbon copies I made of it to neighbors. Over the decades since that time, I have written multiple newspaper columns, magazine columns and articles (including cover stories), blogs, copy for a local political committee and candidates, contributed chapters to two anthologies of short stories, and have written six, as yet unpublished and unproduced books and plays, and a rock opera.

My “breakthrough” came when I wrote Pignon Scorbion & the Barbershop Detectives, an historical fiction mystery novel set in the countryside town of Haxford, England in 1910. It will be published in hardcover by Blackstone on February 8, 2022. An eccentric, but gifted police inspector named Pignon Scorbion, who possesses the skills of Poirot and Holmes, comes to Haxford to head its law enforcement. Through a prior friendship with the town’s barber, Scorbion begins solving his cases in the barbershop assisted by a colorful group of amateur sleuth assistants – the barbers, the shoeshine man, a young reporter, and a beautiful and brilliant, female bookshop owner who is more than a match for Scorbion in observation, deduction and brains.

Scorbion’s ‘universe’ includes Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot and Dr. John Watson, with whom Scorbion has become friends, and I’ve written the book in the style of the authors of that time and genre.

DB: What’s in the future for author Rick Bleiweiss?

RB: I’ve completed writing over 95% of Pignon Scorbion & the Barbershop Detectives, Book 2 which I believe will be published in early 2023. Without spoiling anything, it contains a case about a man who is shot and killed by an arrow while riding alone in a hot air balloon, another about the shoeshine man’s visiting cousin who is attacked and brutally beaten, a third involving a blacksmith who is murdered while walking home in the early morning, and lastly, a moneylender who is poisoned and dies in one of the barber’s chairs.

I also have a piece in an anthology of mystery short stories called Hotel California that is publishing in May, 2022. I join some real heavyweights in the book including Heather Graham, Andrew Child (who has contributed a new Jack Reacher story to the anthology), Amanda Flower, Reed Farrel Coleman, John Gilstrap, Jennifer Dornbush, and Don Bruns, all of whom have written new stories for the volume.

My story is about a premier NYC hitman named Walker who escapes a hit on his life and hides out in Maui while another hitman is sent to finish him off. It’s a cat and mouse game of who gets who.

I also will have another Walker story in the follow-up anthology, Thriller, due in mid-2023.

Lastly, at least for now, in January I have stories being published in Strand Magazine detailing a lot of the research I did for the Scorbion book, and another in Crime Reads Magazine in which I talk in depth about my favorite all-time mystery authors.

DB: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

RB: We are launching Scorbion in a somewhat unconventional manner. There is a Pignon Scorbion ‘Find the Hidden Objects” video game that will be available for free on the Apple and Android app stores. It will have six levels based on scenes in the book, but you will have to input an unlock code to play the last two – and that code is in the book and the audiobook. Shane Salerno of the Story Factory made a wonderful video trailer for the book, there will be retail display contests, we are making and will be selling Scorbion t-shirts, the book has already been voted the Buzz Book of the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Assn’s fall conference, has been featured multiple times in Publishers Weekly (including an excellent review), will be featured by BookBub on publication date, I am hosting a YouTube show interviewing authors and literary agents as they talk about their careers and give advice to aspiring authors, and we are going to make a strong media push hoping to get what I’m doing at 77 years of age as an example to other seniors that you are never too old to try something new or follow your dreams.

~~~

Thank you, Rick, for joining us at The Kill Zone. Best of luck with the February 2022 launch of Pignon Scorbion & The Barbershop Detectives!

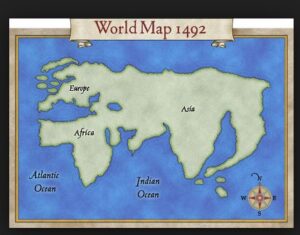

Discover: verb. to see, get knowledge of, learn of, find, or find out; gain sight or knowledge of (something previously unseen or unknown).

Before I begin, let me note that I’m not addressing the issues of the treatment of indigenous peoples by the early explorers. I’m simply looking at the accidental discovery of the Americas.

One might argue that Columbus didn’t “discover” the New World since people already lived there. Others may point out that Norsemen landed in Newfoundland hundreds of years before Columbus. But the discovery in 1492 was the singular event that led to a worldwide understanding of the geography of our planet and resulted in an exciting new age of exploration.

In the fifteenth century, many European leaders longed for quick access to the riches of the Far East, but land travel to Asia was perilous. The only known sea route was by sailing south along the west coast of Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, across the Indian Ocean and on to Asia. But that was a long, slow journey.

Into this moment in history stepped the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, and as we all know, he proposed a different solution to the problem: sailing directly west from Europe to Asia. Columbus wasn’t the only person who believed the Earth was round – most educated people of that era agreed – but he was the one who was willing to risk his life on it.

Columbus was an excellent seaman and one of the most experienced navigators of his time. However, the data he used to calculate the length of the voyage was faulty. The circumference of the Earth was considered to be much smaller than it actually is, and the Asian land mass was thought to extend much farther to the east than it does. Using these data, he calculated the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan to be about 2,400 miles. Actually, it’s more than 10,000 miles. One can only wonder if he would have attempted the voyage if he had known the true distance.

By 1484, Columbus had drawn up plans for a westward expedition into the Atlantic Ocean to fulfill the dream of finding a faster route to Asia and its riches, but his request for support was turned down by every government he approached as being too risky. Undeterred, he kept trying, and eventually he secured funding from several sources including the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. The rest, as they say, is history.

***

Perhaps we can define Christopher Columbus as the first hybrid plotter/pantser. (Okay, now you see where I’m going with this.) There are a lot of similarities. Columbus had an end goal in mind, but he didn’t simply hop in a boat and head out. His persistence and hard work got his voyage funded. He used the knowledge that was available to him at the time to plan his voyage (albeit his calculation of the length of the trip was woefully mistaken). He was a skilled navigator who had made many successful voyages around the coasts of Europe, and he wisely decided on the starting point from the Canary Islands to take advantage of the favorable trade winds. Still, to set sail into the unknown was an act of courage and faith that I suspect few had then or have today.

Of course, he could not have foreseen the magnificent surprise that awaited him some weeks after he set sail.

***

The Discovery Method in writing is often defined as pantsing or “writing by the seat of your pants.” But maybe it’s closer to the Christopher Columbus hybrid method. Is using this approach a way to happen onto an idea or a phrase that we wouldn’t have come upon otherwise? Will the discovery method offer us the opportunity to learn more about ourselves by launching into the unknown with a partially-developed plan? Is it possible to produce a work that is new and revolutionary through the discovery method?

So, TKZers: Are you a plotter? A pantser? Or a hybrid plantser? Have you happened onto any unexpected discoveries in your writing? Maybe you’ve experimented with a new idea to extend yourself beyond the safe haven of what has always worked for you.

Is the possibility of discovering something new worth the risk of failure by launching out into the unknown?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I love rooting around in Project Gutenberg. This amazing site has been digitizing public domain works since 1971! But wait, there was no internet then, so what gives? A visionary, that’s what. A 24-year-old grad student named Michael Hart at the University of Illinois foresaw the coming of a network of computers sharing knowledge. Gaining access to a university mainframe, he started adding digitized literary works in the public domain.

I love rooting around in Project Gutenberg. This amazing site has been digitizing public domain works since 1971! But wait, there was no internet then, so what gives? A visionary, that’s what. A 24-year-old grad student named Michael Hart at the University of Illinois foresaw the coming of a network of computers sharing knowledge. Gaining access to a university mainframe, he started adding digitized literary works in the public domain.

Thus, Hart was the inventor of the ebook. Really.

He spent the rest of his life (he died in 2011) dedicated to his project, which he called Gutenberg. And how did the books get digitized and uploaded? They were hand typed! By Hart himself and a team of volunteers. This work went on for 25 years until the coming of scanning technology. Since that time Gutenberg’s growth has exploded. It now has over 66,000 works in its collection available for free download on any reading device. Among works that have just come into public domain are Winnie-the-Pooh and The Sun Also Rises.

And not just books. Gutenberg is adding pulp magazine stories from the golden age, e.g., science fiction, detective. Also some audiobook versions. I have dozens of Gutenberg books on my Kindle.

I get their daily update and always find some interesting titles to have a look at. The other day it was Modern Essays and Stories: A Book to Awaken Appreciation of Modern Prose, and to Develop Ability and Originality in Writing by Frederick Houk Law, Ph.D., published in 1922.

Dipping inside, I came across the entry on what makes a good short story.

Brevity is the first essential of a short story, and yet under the term, “brief,” may be included a story that is told in one or two paragraphs, and a story that is told in many pages. A story that is so long that it cannot be read easily at a single sitting is not a short story.

That’s a good definition, as it includes what we now call flash fiction, and draws the line before crossing over into the novelette and novella range.

So what does a good short story do?

To make one strong impression on the mind of the reader, and to make that impression so powerfully that it will leave the reader pleased, convinced and emotionally moved is the principal aim of a good short story. To the production of that one effect everything in the story—characters, action, description, and exposition—points with the definiteness of an established purpose. All else is omitted, and thus all the parts of the story are both necessary and harmonious. Centralizing everything on the production of one effect makes every short story complete in itself. The purpose having been accomplished there is nothing more to be said. The end is the end.

Well now! If I may modestly mention my own book on the subject, How to Write Short Stories and Use Them to Further Your Writing Career, this affirms the “secret” I found by analyzing thousands of short stories. I call it “one shattering moment.”

What that moment is depends on the type of story you write. If it’s a crime or mystery story with a “twist,” that’s one kind of moment, and usually comes at the end (see Elaine’s post on that subject here).

Another type of story is the one that lays you flat with an emotional punch. Here the shattering moment may happen in the middle, as it often does in a Raymond Carver story. The emotional shattering can come at the end, as in Irwin Shaw’s classic “The Girls in Their Summer Dresses.”

Keeping one shattering moment in mind gives you all the direction you’ll need to write a short story worth reading. Just add your own stamp and creativity.

A good short story can be a gateway for readers to discover you and your full-length books. So where can you publish? There are established venues, like Alfred Hitchcock and Analog. These can be hard to crack and take a long time to hear from.

Some authors, like yours truly, use Patreon. (Hey, can I urge you to give it a try? No obligation, and I’d love to hear what you think!)

Many more use sites like Wattpad, Medium, and Comaful. Heck, you can start your own blog just for short stories.

Or why not go right to Kindle? Publish it in Kindle Select, price it at 99¢, and run a free promo every 90 days. Make sure you have links to your website and books in the back matter.

And if you can find a real bookstore with a window, you can sit there and type a story on the spot, like Harlan Ellison used to do. Ha!

Short stories and flash fiction are good ways to keep your creative muscles juiced, and offer a nice respite from full-length fiction. And if you can give readers that shattering moment, they’ll come looking for your other work!

***

BONUS: For you craft fans, I’m participating in a great StoryBundle of writing books. Check out how you can get them all at Write for the Win.

by Steve Hooley

Today is National Hat Day. The topic is the hat, more specifically the type of hat and the telling detail.

So, let’s put on our writer’s hat, take off our hat to the “telling detail,” and hang our hat on the proposition that the hat may be the best telling detail.

I had no idea that hats were so popular. When I looked on Pixaby for an image of a hat, I found 101 pages with 10,012 images. Who knew? People love their hats (their specific hat). Consider a number of idioms that use the word “hat.”

And then there’s a list of superstitions about hats. which we won’t go into.

The following is some information listed on the National Day Calendar:

Since at least 1983, National Hat Day has been observed in libraries, schools, and museums. They have invited students and patrons to wear their favorite hat or hats of their occupation. People of all ages show up in pirate hats and football helmets. Patrol officers, postal workers, restaurant servicers also wear their hats to various events. That date also commemorates the day in 1797 when the first top hat made its appearance in court. Created by haberdasher John Hetherington, the judge claimed the tall, rather prominent hat disturbed the public.

Again, according to the National Day Calendar:

We wear hats for numerous reasons. Many hats protect us from elements or harm. Others were worn for ceremonial or religious reasons. Some hats just make us look good or cover up what we think doesn’t. Through the centuries, we’ve given our hats a lot of meaning.

Okay, now to the telling detail. Besides social status and occupation, hats often tell us about attitude or what people think of themselves. I noticed on Pixabay that some people (I’m not mentioning gender) seemed to think “their” hat said it all, or at least “they” didn’t need to wear anything else. (Don’t everyone rush over there at the same time to look.)

This all made me finally realize—okay, I’m a slow learner—that instead of flowery descriptions of characters’ height, weight, eye color, hair color, fit and expense of clothing, etc., etc., what we really need to know is what kind of hat do they wear.

Yes, I’m exaggerating to make a point. A majority of people don’t wear hats. But what better telling detail can you find than the character’s hat? I’m certain that you will find some. That’s the point of today’s exercise.

And, if you don’t wear a hat, and want to know all the different styles, and what would be right for you and your personality, here are links to hat styles for men and women:

Now that we’ve reviewed hats, it’s your turn:

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets

I’d rather write an entire mystery than come up with a title for it. So much depends on choosing the right name for your baby: Will your title grab the reader? Describe your book? Boost your sales?

If you’re writing for a traditional publisher, your contract will probably call your mystery Untitled Work. It’s your job to give it a snappier name. You’ve lived with this book for months, even years. Maybe you’re too close to think of a good title. It’s time to step back and take a look at tips for mystery titles.

Ask your family and friends. I originally wanted to call my Angela Richman mystery about the murder of an aging Hollywood diva, Death Star. My editor said the title sounded too much like science-fiction. My husband Don came up with a play on a classic movie title. The new book was christened A Star Is Dead.

Keep Your Title Short. Yes, I know The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo wasn’t hurt by its long name. But short, snappy titles sell well. Consider Michael Connelly’s mysteries, starting with Black Echo. His titles are short and to the point. Stephen Cannell was another master of titles. My favorite is The Vertical Coffin, which he said was a cop term. When the first law enforcement officer rushes the door in a takedown, that doorway can quickly become a vertical coffin. Especially if firearms are used.

Early in my career, I wrote a collection of humor columns called The Viets Guide to Sex, Travel and Anything Else that Will Sell This Book. Lots of laughing readers didn’t line up for that title. Instead, drooling old men infested my signings, saying, “I want that book on sex travel.” Apparently the old boys missed that comma between Sex and Travel in the title. My mystery novels with titles like Killer Cuts attracted a better reader.

Search Shakespeare. Some authors, including Marcia Talley, find titles in the Bard’s work. My favorite Talley title is Unbreathed Memories, a phrase from “Midsummer Night’s Dream.” You can hunt for titles in OpenSourceShakespeare.org

Hymns and the Bible. Julia Spencer-Fleming has found a number of titles in hymns, beginning with In the Bleak Midwinter. They are perfect for her Rev. Clare Fergusson series.

Want to go trendy? For a while every third book had “Girl” in the title. That trend started with novels like Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train, not to mention The Girls With the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson. None of these women were the girl next door, but their books sold. By the way, The Girl Next Door was used by a wide range of writers, from Brad Parks to Ruth Rendall. It’s even a horror story.

Want to go trendy? For a while every third book had “Girl” in the title. That trend started with novels like Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train, not to mention The Girls With the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson. None of these women were the girl next door, but their books sold. By the way, The Girl Next Door was used by a wide range of writers, from Brad Parks to Ruth Rendall. It’s even a horror story.

There were also a raft of “Daughters,” as in Leslie Welsh’s The Serial Killer’s Daughter. Now I’m seeing lots of “Wives,” including Daisy Wood’s debut novel, The Clockmaker’s Wife, and Alice Hunter’s The Serial Killer’s Wife.

One word titles can sum up the book. This works well for thrillers, such as Jeff Abbott’s Panic and Aaron Elkins’ Loot. I had a one-word title for a Dead-End Job mystery. I wanted to call the book Catnapped, but there was another mystery with the same name that year.

My editor added an exclamation point to the title and made it Catnapped!, leaving me with a punctuation nightmare. How would you end this sentence: “I hope you like Catnapped!”

Should I add a period at the end of this sentence: “I hope you like Catnapped!.”

Or keep the exclamation point and look like a hyper-excited ditz?

Some words have a mystery mystique. Currently on the Pub Alley Fiction Mystery Bestsellers list are titles with words that seem to grab readers:

Paris. Gets them every time. At the top of the list is The Paris Detective: Three Detective Luc Moncrief Thrillers by James Patterson and Richard Dilallo.

Curse. Another intriguing word. Curse of Salem by Kay Hooper made the list.

Midnight. Two titles with “Midnight” are on the list: The Midnight Lock by Jeffrey Deaver and The Midnight Hour by Elly Griffiths.

Book Title Generators are another tool for clueless mystery writers. You can find several of them here: https://kindlepreneur.com/free-book-title-generator-tools/

I sampled the Mystery Book Title Generator, which claims to be the “Ultimate Bank of 10,000 Titles” that will “generate a random story title that’s relevant to your genre. You can pick between fantasy, crime, mystery, romance, or sci-fi.” http://blog.reedsy.com/book-title-generator/mystery

I clicked on “I’m just starting to write” and got this title: “The Mystery of the Three-Inch Stranger,” which struck me as a bit personal. It’s not the size of the stranger, it’s what you do with him.

Series titles: Sue Grafton has her alphabet series, beginning with A Is for Alibi and ending with Y Is for Yesterday. Mary Higgins Clark and her partner-in-crime Alafair Burke have a song title series, starting with You Don’t Own Me. Stephanie Plum uses numbers. Her latest is Game on: Tempting Twenty-eight.

Series titles: Sue Grafton has her alphabet series, beginning with A Is for Alibi and ending with Y Is for Yesterday. Mary Higgins Clark and her partner-in-crime Alafair Burke have a song title series, starting with You Don’t Own Me. Stephanie Plum uses numbers. Her latest is Game on: Tempting Twenty-eight.

I’d wanted to call my first novel for Penguin The Dead-End Job. My editor thought that would make a good series title, so that book became Shop Till You Drop.

When you write for a publisher, potential titles are batted back and forth. My fourth mystery in that series featured the murder of an overbearing mother of the bride. I wanted to call it One Dead Mother.

My publisher nixed that title as “too urban.” The novel was named Just Murdered.

Enter to win a free copy of Life Without Parole, my latest Angela Richman, death investigator mystery. Stop by Kings River Life magazine: https://www.krlnews.com/2022/01/life-without-parole-angela-richman.html

Enter to win a free copy of Life Without Parole, my latest Angela Richman, death investigator mystery. Stop by Kings River Life magazine: https://www.krlnews.com/2022/01/life-without-parole-angela-richman.html

I’ve heard writing instructors over the years tout the three elements of storytelling: plot, character and setting. We all know what the words mean, and we know how they apply to creating entertaining fiction, but all too often, I think that new writers think of the elements as craft silos instead of the strands of a craft cable–intertwined elements that must work together if a story is going to resonate with the reader.

I prefer to think of the elements this way: interesting characters doing interesting things in interesting ways in interesting places. (If you’d prefer, you can replace “interesting” with “compelling”.)

Character is king. A plot by itself is merely an outline. It doesn’t come to life until the reader experiences the plot through the eyes and feelings of a character they care about. Setting is merely a descriptive essay until a character interacts with it.

Let’s say, for example, a section of your story is set in a desert on a hot afternoon. An English 101 professor would likely be happy to reward an essay that presents a mental snapshot of the bright sun, colorful rocks and sparse flora. That reporting of facts might please a newspaper editor as well.

But look what happens when we inject characters into the equation:

Bob pushed the door open and climbed out into the brilliant sunshine. Shielding his eyes, he scanned the horizon. The beauty of the place took his breath away. Rock formations glistened in shades of copper, gold and bronze. The vegetation, while sparse, seemed to vibrate with intense reds and blues and yellows. He was stranded in an artist’s paradise.

The description, as presented to the reader, also lets us learn about Bob’s worldview. We don’t have to say that he thinks the place is beautiful, because that’s all in the narrative voice.

Here’s another description of the exact same scene, but filtered through the worldview of a very different character:

Opening the car door was like opening a blast furnace. Superheated air hit Danny with what felt like a physical blow. The desiccated ground cracked under his feet as he stood. As he took in scrub growth and the rocky horizon, he understood that he no longer rested at the top of the food chain. Now he understood why we tested nukes in places like this.

A desert is a desert, right? From a plot perspective, each description takes the story to the exact same place, but by filtering the observations through the characters’ souls, the reader gets to know them better, and they don’t have to endure a disembodied descriptive paragraph.

That voice of the character can infect every paragraph of every scene. I like to say that I make a point as the writer for MY voice to be invisible throughout every story. Every scene is presented to the reader through the voice and view of the scene’s POV character. This is less complicated (note I didn’t say easier) in a first person POV, I think, because the narrator tells the entire story. When writing in third person, one of the critical decisions the writer needs to make for every scene is to determine to whom the scene belongs.

Consider this: Your story requires a scene where a thirteen year old boy steps out the back door of a bar at midnight and lights a cigarette. Let’s say that the kid is signaling someone with the match.

If we present the scene from the kid’s point of view, if he chokes on the smoke, we have a character detail that is different than if he were to inhale deeply and find peace. Is his heart pounding, or is he calm?

If we present the scene from the point of view of the guy being signaled to, his voice will tell us whether he likes the kid or hates him. Is the signal a happy event or a troubling event?

Perhaps we present the scene from the point of view of a passing cop. That would put the story on a different path–unless, perhaps, the cop was the one being signaled.

Assuming that any of the points of view would advance the plot to the same point, we need to decide whose POV is most compelling for the reader. Let’s say now that the scene ends with the kid getting shot. Perhaps we start the scene from the kid’s point of view, and then switch after a space break to the shooter’s POV. Or, vice versa.

These decisions make all the difference between a compelling story and a ho-hum one.

So, TKZ brain trust, what are your thoughts? Do your characters drive every beat of your story?