How to Break into a Library

by Dale Ivan Smith

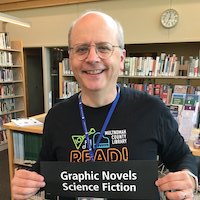

Today, we are honored to have one of our TKZ community, Dale Ivan Smith, as a guest contributor. Dale has worked as a librarian in Portland, Oregon, for over thirty-two years, so he brings us years of experience and some great advice for authors who want to work with libraries and librarians. Thanks for your post, Dale.

No, I’m not talking about how to break into a public library. Okay, I am, but not in the criminal sense. I’m here to talk about how to get into the library as an author. Not just the physical public library, but the digital one, too. I spent over thirty years working in Oregon’s largest public library system, Multnomah County Library, which, at least prior to the pandemic, was one of the busiest libraries in the United States.

Though I worked in public libraries, including managing the science fiction and fantasy collection at my regional branch, I’ll also share a couple of tips for getting into schools and school libraries as an author. I retired in December 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic. That said, in conversations with my former boss and others still working at the library, there’s every reason to expect that libraries will still operate after the pandemic much like they did before, which means they’ll need programming and new books.

The modern public library is a dynamic place—people (“patrons” in library speak) come in order to borrow all sorts of physical media, books, DVDs, CDs, etc.; and to use computers and Wi-Fi; meeting room space for book clubs, neighborhood committees, job seekers, chess clubs, etc. Especially important are programs, ranging from story times for children and families, to puppet shows, art and craft events, local history presentations, computer classes, etc.

Meanwhile, the digital side of the library is open 24/7 via the Internet. eBooks have become very popular with patrons, as have digital audiobooks, which can be downloaded directly to your tablet or smart phone.

During the pandemic, Multnomah County Library has continued to offer story times and other programs via Zoom, including the library sponsored Pageturners Book discussion groups.

What is in it for you, the author?

Libraries have avid readers, and thus are always on the lookout for great reads, and informative non-fiction, so this is a chance to reach another audience, and make some new avid fans. Libraries give you the opportunity to meet readers, too.

Local author love

Libraries love local authors. Lead with that when you introduce yourself. If your book is about a true crime based on a local incident, or a mystery novel set in the area, mention that. It’s an important connection to the community, and libraries really value that connection. However, simply being a local author is important, because you are part of the community the library values, and the librarian will be interested in you as an author because of that local connection.

Incidentally, chances are the first staff member you encounter will not be an official “librarian.” People naturally consider anyone who works at a library a “librarian.” However, in library-land librarians are a professional job class requiring a master’s degree in library sciences. I was a para-librarian, called a library assistant in my system, because I had a degree in history but not an MLS. I could do most of the things a librarian did, except for cataloging books and other materials, and I wasn’t considered the last word in information service (just close to it). The staff who might check out your books are probably library clerks, access service assistants, etc. ASAs and “pages” do much of the shelving, helped by volunteers and other staff, including often para-librarians. So, when you drop by for a visit, that first staff person you encounter will take you to the librarian, unless it’s a really small library, in which case that person very likely is the professional librarian.

Calling to speak to a librarian about your book or a possible speaking opportunity is a better option than “cold emailing” out of the blue. My last boss told me he was regularly barraged by emails from authors from other parts of the country, who composed generic emails which they sent to libraries nationwide. A much better approach is to start with your local library and work outward to other neighboring libraries, and then libraries in nearby cities, and eventually in neighboring states. You establish contacts with librarians and begin to build a track record of presentations and as well as being able to point to other libraries that already have your books in their collections. It also helps emphasize you being a local author.

If you end up having to email, it’s worth taking the time to visit the library’s website and learn more about them. But, in my experience, a visit or a phone call is preferable.

Giving a program at the library

Speaking of speaking opportunities, giving a reading by itself can be a tough sell for librarians. A better approach is to look at leveraging an aspect of your book or writing and offer that topic as a program event to your library. Are you a former homicide detective? Then giving a presentation or program on forensics would appeal to librarians. Write about true crime topics? That would be a draw. Write culinary cozies? A cooking program or culinary presentation might make a great program for the library. If there’s a local history or local culture aspect to your book, that works too. Many readers dream of writing, so a writing program is another angle. Almost any area of knowledge from your books can be turned into a potential program item, running an hour, an hour and a half, or even two hours. That could include a reading from your novel, non-fiction or true crime, perhaps at the end of your presentation.

Another speaking opportunity is to see if your book might fit a book club or discussion group held at your local library branch. Once again, being a local author will increase potential interest. Book discussion groups in my library system typically select the books they are going to read for the coming year in late spring or summer. Check with your local librarians about this, since one of them is probably the library contact for the group and let them know you would d be interested in having your book considered. You could then “guest star” at the book discussion and give a short reading. The same if your library has a kids or teens reading group, and your book fits either of those ages.

The Power of Suggestion

Libraries heavily favor patron requests and recommendations when it comes to purchasing books. They want to build a collection that will be used. They keep abreast of trends, and current reader interests. Incidentally, libraries need their physical books to be checked out. Around half of our books were checked out at any time. There isn’t typically enough shelf-space to hold all the books in a library collection. Which means owning books which will be borrowed, and discarding books that aren’t being used, to make room for other books. The digital library side is a different matter, of course, since physical space isn’t an issue.

Patrons can fill out online “suggestion for purchase” forms, usually by first logging in with their individual library card and tell the library about a book they want the library to add to its collection. Pro tip: put a call out to your newsletter to let your readers know that they can request that their local library purchase your books. This is a great service to your readers, because it gives them the opportunity to read your books for free.

Availability

If you are an indie author, making your books available in print via Ingram Spark will make it much easier for the library to add them to their collections. I have had print editions of my novels purchased by libraries via Kindle Direct Publishing’s print on demand option, but librarians are much more comfortable with the options provided by IS, which also lists with Baker and Taylor, one of the bigger book distributors for libraries.

As for eBooks, library systems in many countries use Overdrive as their eBook platform. Bibliotheca and Hoopla are two others. As long as you are not exclusive with Amazon for your eBooks (i.e., they aren’t enrolled in Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited program), you can make them available to public libraries.

Kobo Writing Life, Draft2Digital, and Smashwords all let you put your books in the Overdrive catalog. D2D also lets you list with Hoopla, which is a streaming service for libraries which can include eBooks, as well as Baker and Taylor, and both D2D and Smashwords let you include your books in Bibliotecha.

Another way for your self-published book to get into the library

Another option is to check if your library has a library writers project, a program which lets self-published authors submit one of their books to be considered for the library collection. These writer’s projects are for local authors (there’s that local connection again), but in the case of my library system, “local” is a pretty broad area.

The book trifecta: Content, presentation and format

Not only do librarians want books that readers will enjoy—engrossing thrillers, fun cozy mysteries, gripping true crime stories, for instance—they want books that are edited and proofread, with professional covers, well-written back matter copy, and proper formatting. Formatting matters, both eBook and print. We saw a number of self-published print titles that had small fonts, or odd line-spacing to pad out the book, as well as covers that didn’t effectively convey the genre. Professional-looking presentation and formatting signal that this is a title worth adding to the library’s collection.

Librarians also rely on reviews for making many of their book purchasing decisions. Library Journal, School Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, Booklist, Publishers Weekly, and others are important for both making librarians aware of new titles and giving them a sense of quality and who the audience for the book might be. These mainly review trad-published books. However, if your indie-published novel was reviewed on a website or in a publication, by all means mention that in your conversation or email.

Tips for School libraries

Again, start local. Visit your local library and chat with the youth librarian and see if they can refer you to their local school counterpart. You’ll likely have to call or email the school librarian. Personalize your email. Emphasize being a local author, see if they would be interested in an author visit, and mention any program ideas you have, for example, a presentation on medicine aimed at kids.

You can also check the website of your local school district. It will probably list individual schools. Locate an age-appropriate-to-your-books school and look for the school librarian. Some districts have district librarians, so that could be a great person to begin with.

Like public libraries, schools also rely on professional journals and publications, including Hornbook, School Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, Booklist, and Publishers Weekly. They do the bulk of their purchasing through “book jobbers” that provide cataloging and processing services, and which include reviews in their ordering interfaces.

Another resource

An Author’s Guide to Working with Libraries and Bookstores, by Mark Leslie Lefebvre

An excellent, in depth looking at working with librarians and libraries. A deep dive into the details, including a plan for starting locally and then expanding outward. The author does a terrific job of laying out what libraries and librarians want, as well as discussing pricing strategies, further advice on connecting with librarians, etc.

Q&A with Steve Hooley

Do you think most librarians will prefer physical or zoom meetings as we move into 2021? I think once libraries open up again, librarians would love to have authors drop by to introduce themselves. Programming in building will eventually resume, too, though it’s certainly possibly that programs and book discussion groups may also continue via Zoom.

Is it a good idea to offer a free book? Would a librarian hope for or expect a free book? You can certainly ask if they’d like a copy of your book to look at, but very likely they won’t be able to add the book to their collection, unless they are a small, single building library. My library has acquisitions librarians who order books and multimedia. Distributors would already have done some of the cataloging work and labeling before the book reached the library, which really helped, since my system was processing as many as fifty thousand new items each month.

Would most librarians prefer to hear from writers occasionally, or are they so busy that they would be happy to hear from writers only when they have a new book out? Librarians tend to be pretty busy, so when touching base when you have a new book out would be appreciated.

Is it appropriate to offer librarians the opportunity to sign up for a newsletter? I don’t think it would hurt to mention that you have a newsletter, but unless the librarian is personally interested, they may pass, given how busy they are.

Is there any etiquette for an appropriate gift to a librarian after a speaking engagement arranged by the library? Chocolate is almost always appreciated. But a gift isn’t necessary, after all, if you give a presentation, or program, or guest star at a book discussion group, you have already given the library the gift of your time!

What do librarians want most from writers? To keep in mind that libraries aren’t bookstores, but places where librarians love connecting readers with books they’ll enjoy, as well as community meeting places, where programs offer patrons a variety of interests.

***

I want to thank Steve for inviting me to guest blog today, and to the entire TKZ community for all the inspiring and informative posts and comments and interactions over many years, it’s truly made a difference for me as a writer and author.

***

Thanks, Dale, for a wonderful post. I’m certain we’ve all learned some new ideas. And now, TKZ community, here’s your chance to ask our resident librarian questions about libraries and librarians:

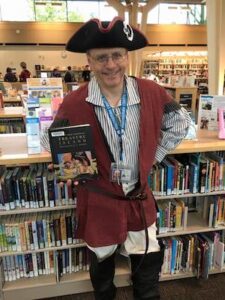

Dale Ivan Smith is a lifelong resident of the beautiful Pacific Northwest. He got into trouble in grade school for sneaking off to the library during math class, so naturally he wound up working as a librarian for Oregon’s largest library system, Multnomah County Library, in Portland, Oregon, where he worked at four different branches. After thirty-two years, he retired in December 2019 to write full time.

Dale’s published novels include the contemporary fantasy series THE EMPOWERED, which begins with EMPOWERED:AGENT, the urban fantasy GREMLIN NIGHT, and the space opera SPICE CRIMES. After wanting to combine his love of mysteries and libraries for years, at long last Dale is now working on a library mystery series. His website is https://daleivansmith.com. He’s on Twitter as @daleivan.

Who says librarians can’t be pirates?

This story was difficult to write, because my protagonist was so dislikeable. We learn straight out that Tiffany Yokum is a gold digger – and a calculating killer.

This story was difficult to write, because my protagonist was so dislikeable. We learn straight out that Tiffany Yokum is a gold digger – and a calculating killer. The award-winning Evan Hunter – a.k.a. Ed McBain – made that recommendation. It works if your villains aren’t too evil. McBain had a lot of sniffling and sneezing detectives in the 87th Precinct. But I could give Tiffany pneumonia – heck, Covid-19 – and she still wouldn’t be likeable.

The award-winning Evan Hunter – a.k.a. Ed McBain – made that recommendation. It works if your villains aren’t too evil. McBain had a lot of sniffling and sneezing detectives in the 87th Precinct. But I could give Tiffany pneumonia – heck, Covid-19 – and she still wouldn’t be likeable.

Tiffany quickly becomes the fourth wife of rich old Cole Osborne and they live in luxury in Fort Lauderdale.

Tiffany quickly becomes the fourth wife of rich old Cole Osborne and they live in luxury in Fort Lauderdale. The Joni Mitchell song was Tiffany’s anthem, and she recognized herself in the lyrics of “Dog Eat Dog.” Especially the part about slaves. Some were well-treated . . .

The Joni Mitchell song was Tiffany’s anthem, and she recognized herself in the lyrics of “Dog Eat Dog.” Especially the part about slaves. Some were well-treated . . . Cindy knew she’s landed her pretty derriere in a tub of butter, but she knew her work has just started. Among other things, Cindy changed her name to a classier “Tish.”

Cindy knew she’s landed her pretty derriere in a tub of butter, but she knew her work has just started. Among other things, Cindy changed her name to a classier “Tish.”

Tiffany says, “I thought I could sail smoothly into Cole’s sunset years and collect the cash when he went to his reward. But then that damn preacher showed up. The smarmy Reverend Joseph Starr, mega-millionaire pastor of Starr in the Heavens.”

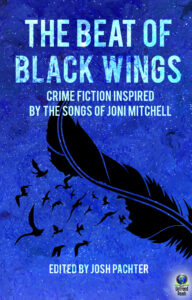

Tiffany says, “I thought I could sail smoothly into Cole’s sunset years and collect the cash when he went to his reward. But then that damn preacher showed up. The smarmy Reverend Joseph Starr, mega-millionaire pastor of Starr in the Heavens.” The Beat of Black Wings, edited by Josh Pachter, is an anthology of 28 crime writers who wrote short stories inspired by Joni Mitchell’s lyrics. The award-winning authors include Art Taylor and Tara Laskowski, Kathryn O’Sullivan, Stacy Woodson, and Donna Andrews. A third of the royalties will be donated to the Brain Aneurysm Foundation in Joni Mitchell’s name.

The Beat of Black Wings, edited by Josh Pachter, is an anthology of 28 crime writers who wrote short stories inspired by Joni Mitchell’s lyrics. The award-winning authors include Art Taylor and Tara Laskowski, Kathryn O’Sullivan, Stacy Woodson, and Donna Andrews. A third of the royalties will be donated to the Brain Aneurysm Foundation in Joni Mitchell’s name.

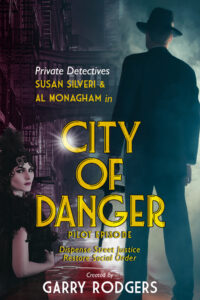

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit.

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit. Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline:

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline: