Where Did That Come From?

Terry Odell and James L’Eotile

As I’m still in New Zealand, I’m delighted to have James L’Etoile as my guest today. I first met James at a Left Coast Crime conference, where he endeared himself to me forever by handing out chocolates wrapped with images of his recent release’s cover. Yes, chocolates. Yes, I’m easy. Oh, and he writes good books, too. I have no idea what day or time it is, or when or if I’ll have internet access, so James will be responding to comments. Take it away, James.

Hey there! Terry left a key under a rock by the back door and told me to let myself in. Terry was nice enough to offer me a guest post slot here on The Kill Zone if I promised to clean up after myself. I found a note reminding me no loud parties and be mindful of the curfew. Terry asked me to talk about how I went from a life of crime to writing about it. She may not have phrased it exactly that way…

I was in prison for 29 years as a result of choices I made. Oh, I should probably clarify that I worked in prison as opposed to having been sent there by a judge. I served as a hostage negotiator, captain, associate warden in a maximum-security prison, and director of California’s parole system. Still, it was doing time along with 3,000 men who couldn’t function in society without killing people.

Every day brought new challenges and demonstrated the worst humanity had to offer. My goal at the end of each shift was to have no new holes in my stab-resistant vest. So, what does this have to do with writing crime fiction? It’s not what you might think.

I didn’t begin writing until after I escaped (retired) from prison. One spring morning, I sat in the backyard with my coffee and a book. The coffee was good—the book—no so much. I tossed it aside and muttered, “I could do better than this.” Could I? It became a challenge. Could I lean to write commercial fiction?

Writing commercial crime fiction meant learning story structure. It meant discovering dialogue, tone, point of view, and pacing—all new territory for me. Books, online resources helped, but it wasn’t until I began attending workshops and classes that it started to come together. In particular, I credit the Book Passage Mystery Writers conference with putting me on the right course. It’s a small writer-focused weekend bringing in established authors who present craft sessions and offer their insights and encouragement. It gave me the basic tools of the trade.

But there was something missing. Sure, I had the technical skills in my pocket. But could I truly write crime fiction? The confidence—the can I really do this factor—held me back. Until I thought back to one of the first jobs I held as a probation officer preparing presentence reports for the sentencing judge.

A presentence report gives the judge a complete picture of the case and the defendant. I would interview the convicted person in the jail and get their take on the offense. Did they express remorse? Blame the victim? I read all the investigative reports, interviewed the detectives, spoke with the victim, or the next of kin, all to get a sense of the defendant and the crime. All this information would be cobbled together in a narrative for the judge. Years later, it dawned on me that I’d been writing crimes stories all along.

The realization that I’d done this before was enough to give me the confidence to take on writing crime fiction. I’ve learned how to use my experience in the system to help bring a little authentic flavor to the stories I write.

Face of Greed, for example, was based on one of the first murder cases I worked. The real-life situation was a home invasion which took a deadly turn. A real estate broker was shot in front of his family by three gang members. After they were arrested, the gang members claimed the victim was a drug dealer who had been holding out on them. One claimed the killing was self-defense because the victim pulled a handgun from a floor safe. Their story quickly fell apart, and the gangsters turned on one another for better plea deal. The truth was the home was targeted because the homeowner was believed to keep large sums of cash in his safe. The jury saw through their fiction and quickly convicted all three.

The case stayed with me after all these years and when I thought about a novel with an opening scene featuring a home invasion, I thought—what if there was something more going on in that house?

Now, working on the draft of what will be my twelfth novel, I’ve come to realize it doesn’t get any easier, but I’ve got the tools and confidence to see it through. Oh, I did meet that author—the one whose book I tossed aside. I thanked them for giving me the inspiration to become an author. I didn’t tell them exactly how they inspired my path. Sometimes you don’t need to tell the whole story.

How about you? If you’ve tried something new, where did you find your source of inspiration?

James L’Etoile uses his twenty-nine years behind bars as an influence in his award-winning novels, short stories, and screenplays. He is a former associate warden in a maximum-security prison, a hostage negotiator, and director of California’s state parole system. His novels have been shortlisted or awarded the Lefty, Anthony, Silver Falchion, and the Public Safety Writers Award.

James L’Etoile uses his twenty-nine years behind bars as an influence in his award-winning novels, short stories, and screenplays. He is a former associate warden in a maximum-security prison, a hostage negotiator, and director of California’s state parole system. His novels have been shortlisted or awarded the Lefty, Anthony, Silver Falchion, and the Public Safety Writers Award.

Face of Greed is his most recent novel. Look for Served Cold and River of Lies, coming in 2024. You can find out more at his website, jamesletoile.com

Face of Greed is his most recent novel. Look for Served Cold and River of Lies, coming in 2024. You can find out more at his website, jamesletoile.com

Several weeks ago, Blackstone sent me an ARC (advanced review copy) which I’d requested.

Several weeks ago, Blackstone sent me an ARC (advanced review copy) which I’d requested.

Dr. Danielsson plotted information about these aspects on a three-dimensional graph and plotted the same criteria from Arthur Conan Doyle’s works on the same graph. Christie’s books exhibited a consistency shown visually by her plotted points being clustered together while the points of Doyle’s stories were spread farther apart indicating his works were more dissimilar when compared to each other. This indicated that Doyle’s style had changed through the years while Christie’s had remained remarkably consistent.

Dr. Danielsson plotted information about these aspects on a three-dimensional graph and plotted the same criteria from Arthur Conan Doyle’s works on the same graph. Christie’s books exhibited a consistency shown visually by her plotted points being clustered together while the points of Doyle’s stories were spread farther apart indicating his works were more dissimilar when compared to each other. This indicated that Doyle’s style had changed through the years while Christie’s had remained remarkably consistent.

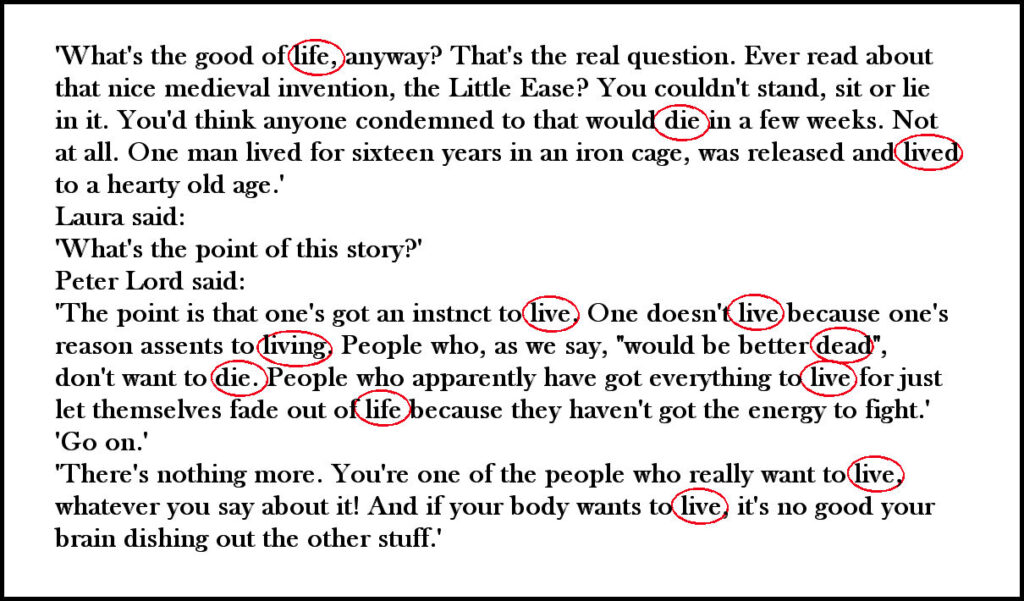

While some famous characters appear in multiple books and are popular with the reading public (e.g., Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, Captain Hastings), the number of characters in each novel may be just as important. This prompted an interesting theory by David Shephard, Master trainer in Neuro-Linguistic Programming.

While some famous characters appear in multiple books and are popular with the reading public (e.g., Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, Captain Hastings), the number of characters in each novel may be just as important. This prompted an interesting theory by David Shephard, Master trainer in Neuro-Linguistic Programming.

Although I found a site with the

Although I found a site with the

“Very few of us are what we seem.” –Agatha Christie

“Very few of us are what we seem.” –Agatha Christie